EVENTS

Kamm Engages Community, Students on Social Justice, Open-Source Research

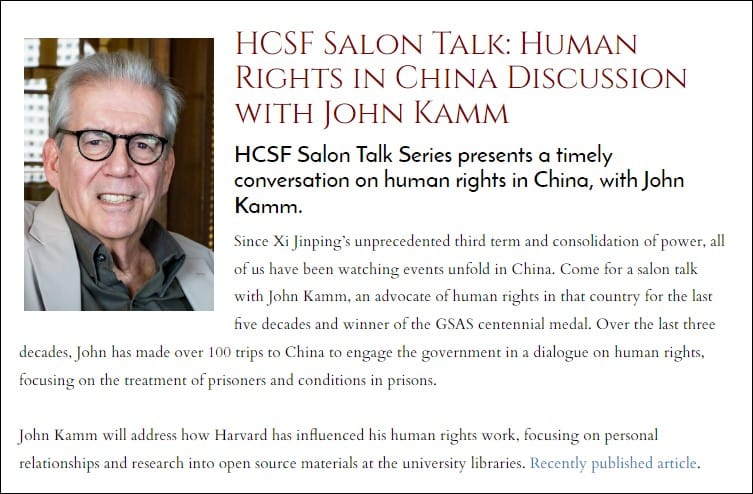

It was a busy February for Dui Hua Executive Director John Kamm. He delivered remarks about Dui Hua’s work and his own evolution from businessman to human rights activist to two diverse audiences: the Harvard Club of San Francisco and the students and faculty of the University of New Haven. Both remarks were delivered virtually.

The speeches were followed by lively Q&A sessions during which Kamm responded to 15-20 questions from engaged audiences.

The address to the Harvard Club of San Francisco took place on the evening of February 8, 2023. In May 2022, Kamm was awarded the Harvard GSAS Centennial medal for his work on human rights. Not surprisingly, the focus of the February 8 remarks was how Harvard prepared Kamm for his career in human rights activism.

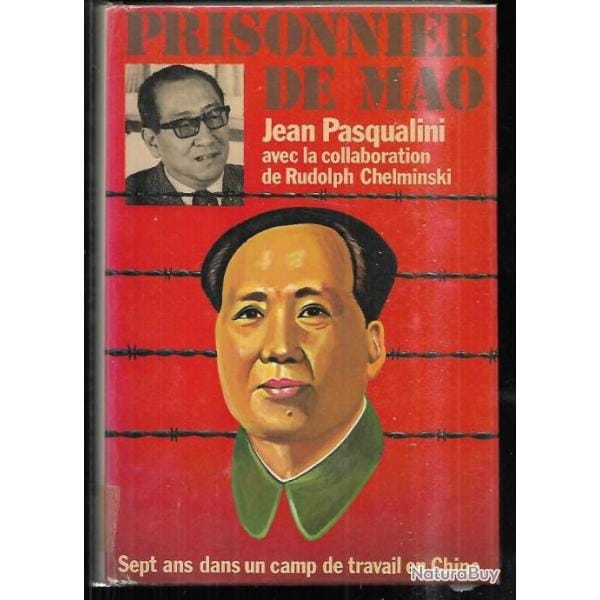

Kamm encountered Harvard in two different periods. In 1974-1975, he studied for a master’s degree in the Regional Studies Department in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. During these two years he took classes from three of the most eminent sinologists in the United States: Yang Liensheng, Dwight Perkins, and Jerry Cohen. In Cohen’s class, Kamm heard from former counterrevolutionary Jean Pasqualini, author of Prisoner of Mao.

After graduation, Kamm returned to Hong Kong and not long afterward he began traveling to China. In the 25 years since his graduation in 1975, Kamm transitioned from businessman to human rights activist, making his first prisoner intervention in May 1990 and establishing Dui Hua in 1999. Right after founding Dui Hua, Kamm began traveling to Cambridge to conduct research in Harvard libraries, speaking to students and community groups, and meeting with alumni and teachers, some of whom were friends and relatives of political prisoners in China.

Kamm gave examples of cases of political prisoners found in Harvard libraries, estimating that more than 1,000 names had been found during many trips back to the university.

On February 23, 2023, Kamm spoke to students and faculty of the University of New Haven as part of the Brehm Boucher Speakers Series. He spoke about his days battling racism at the New Jersey Shore as well as working on human rights in China and US-China relations. The Dui Hua executive director recounted his experience in a town that was a stronghold of the Ku Klux Klan, but which also had a small Chinese restaurant where his mother struck up a friendship with the Chinese woman who ran the eatery.

Kamm then talked about his time at Princeton University. Like many of the students at the University of New Haven, he was the first member of the Kamm family to graduate from college.

At Princeton, Kamm began his life-long study of the Chinese language, but he dropped Chinese after his freshman year and a summer at Middlebury Language School. He concentrated on anthropology and spent the summer of 1971 teaching school to the Ramah Navajos in New Mexico. While at Ramah, he heard on the radio that Henry Kissinger had returned from China to announce that President Richard Nixon were to travel to China in 1972. Kamm resolved to follow in his footsteps. He left the United States for South China in August 1972.

Kamm then described the current state of human rights in China from the perspective of an activist, referring to the “challenging” situations in Xinjiang and Hong Kong and the perils faced by political and religious prisoners. From there he pivoted to a discussion of the state of US-China relations, which Kamm characterized as the worst in his fifty years working in China.

Kamm laced his remarks with “life lessons” he’d picked up on his journey, referencing the importance of learning what his mother called “an exotic language” and studying a major that would enable maximum flexibility in choosing a career. Kamm singled out anthropology as a good major for a business career. Kamm concluded his remarks with a stirring call to work on social justice in the United States and abroad.

PUBLICATIONS ROUND UP

Featured: Guest essay in USALI Perspectives, February 13, 2023: “Of Dialogues and Prisoner Lists” (republished in the Human Rights Journal)

Of Dialogues and Prisoner Lists

As China prepares to resume bilateral human rights dialogues, a human rights advocate reflects on their record

In August 1989, just weeks after the Chinese army opened fire on peaceful protesters in Tiananmen Square, the UN Human Rights Commission’s Subcommission on the Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities passed a resolution censoring China. It was the first and last time that China lost a vote at a UN forum over its human rights record.

Featured: Press Statement, March 2, 2023: “Dui Hua Welcomes the Release of Yao Wentian”

SAN FRANCISCO (MARCH 2, 2023) — Hong Kong publisher Yao Wentian (姚文田) was released from Dongguan Prison in Guangdong province on February 26, 2023. With the exception of an eight-month sentence reduction for good behavior that was granted by the Dongguan Intermediate People’s Court in April 2019, Yao served his entire sentence in Dongguan Prison. News of this reduction was not reported in the media at the time. Dui Hua learned of the sentence reduction decision from an interlocutor and thereafter informed the family. He returned to Hong Kong on February 27, 2023.

See also: Human Rights Journal, February 14, 2023: “Polls Suggest Stormy Waters for Biden, US-China Relations”

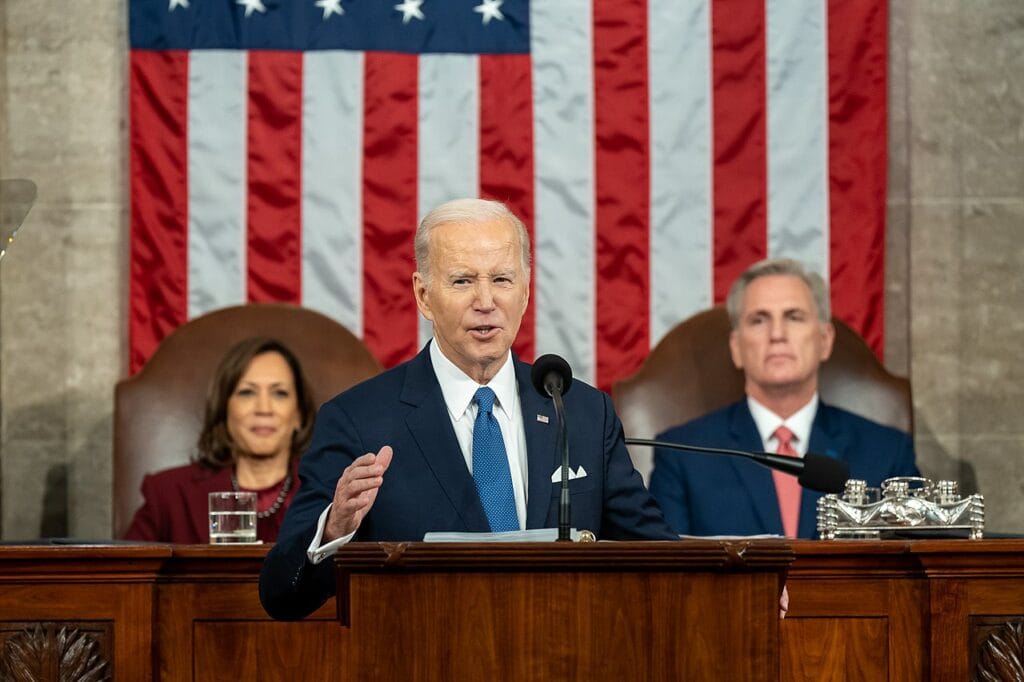

Polling from the start of 2023 suggests that China is increasingly unpopular in the United States as well as in other regions. A majority of Americans are dissatisfied with the Biden administration’s handling of the US-China relationship. Approval ratings for Biden as president are hovering in the 40s, a modest increase from the lows of summer 2022. As per the Harvard/Harris poll from January 18-19: “Biden’s approval is stable but underwater.”

See Also: Human Rights Journal, March 1, 2023: “Criminal Acts: Luzhou Armed Rioting Cases”

The criminal acts of armed rebellion (武装叛乱) and armed rioting (武装暴乱), defined in Article 104 of the Criminal Law, are among the least understood crimes of endangering state security (ESS). They are also among the least frequently invoked in the country. Statistics published by the 12-volume Records of People’s Courts Historical Judicial Statistics: 1949-2016 indicated that Chinese courts only tried 11 cases involving 39 defendants in the 18 years beginning in 1998.

See Also: Prisoner Updates 2023 #3, March 13, 2023:

An artist who recorded daily Covid tests still missing, an academic sentenced for inciting subversion, a Hong Kong publisher freed after almost 10 years, a Wuhan medical welfare protester detained, a political dissenter serving for second jail term, a notable prisoner release, clemency for inmates at Guangdong Provincial Women’s Prison, and Falun Gong practitioners facing trials again in Beijing.

JOHN KAMM REMEMBERS

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s human rights advocacy prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999.

Black Hands

It didn’t take long for the Chinese government to blame foreign and domestic forces for the May-June 1989 protests that rocked Beijing and hundreds of other cities, large and small, throughout the country. The targets of their ire included the United States and other western democracies, which maintained embassies and media offices, in China’s capital. Another target was The Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China, established in May 1989, which organized huge protests and vigils in the British colony. The alliance was disbanded in late 2021 following the arrest of three of its leaders, part of the ongoing crackdown on opposition figures in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

Less organized than the Alliance were groups of activists who set up Operation Yellow Bird to spirit activists out of China. Working out of Hong Kong, this loosely organized group managed to extricate as many as 300 hunted dissidents and activists out of China, sometimes with the help of disgruntled Chinese officials.

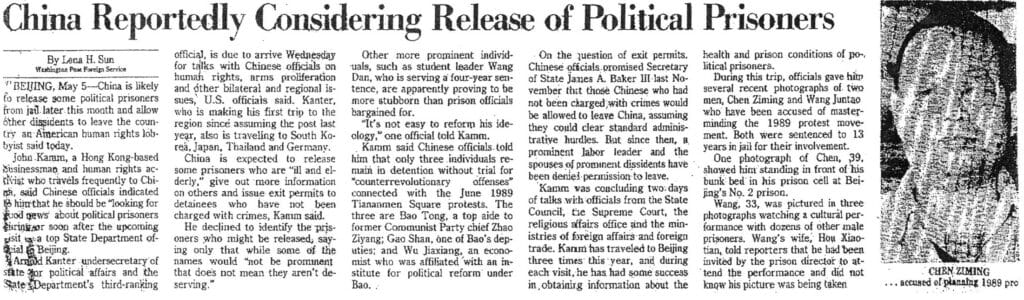

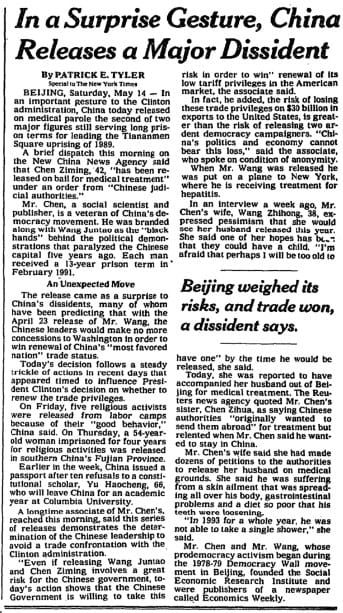

Closer to home, the Public Security Ministry identified 21 student leaders allegedly behind the protests in Tiananmen Square. The list included Wang Dan, Wu’er Kaixi, Chai Ling, and Liu Gang. “Black Hands” were singled out in the “Six Important Criminals List.” Prominent on this list were Chen Ziming (陈子明) and Wang Juntao (王军涛), founders of the Beijing Economic and Social Sciences Research Institute (SESRI), an influential think tank established in 1987 that published books, undertook public polling, and even fielded candidates in local elections. Another black hand was labor leader Han Dongfang (韩东方), founder of the Beijing Autonomous Workers Federation. (A good account of Chen Ziming, Han Dongfang, and Wang Juntao’s activities in the run-up to Tiananmen can be found in Black Hands of Beijing by Robin Munro and George Black. My memories are also informed by communications with Wang Juntao.)

Chen and Wang were hunted down and arrested, Chen on October 10, 1989, in Mongolia, and Wang on October 20, 1989, at the Changsha Train Station in Hunan Province. Liu Gang (刘刚), founder of the Beijing Independent Students Federation, was detained weeks after the protests, on June 19, 1989. Han Dongfang was never tried but was kept in a detention center where he contracted tuberculosis. The prosecution chose not to charge him and eventually let him leave for Hong Kong, where he still lives.

After detention, Chen Ziming and Wang Juntao were held in local detention centers where they were interrogated. They then spent several months in the notorious Qincheng Prison where political prisoners were held.

Chen, Liu, and Wang were all tried and convicted by the Beijing Intermediate People’s Court in 1991. Chen and Wang were given 13-year prison sentences. They were sent back to Qincheng Prison, and eventually sent to Beijing Number Two Prison and Beijing’s Yanching Prison to serve their sentences.

Liu served his prison sentence in Lingyuan Prison in Liaoning Province. It is common practice that individuals who are tried and sentenced in Beijing are returned to their home provinces to serve their sentences.

Reflecting intense international pressure from governments and human rights groups, including Dui Hua, both Wang and Chen were released on medical parole in April 1994 and May 1994, respectively. The releases were tied to President Bill Clinton’s decision to renew China’s Most Favored Relations trade status, without conditions, in May 1994. (Chinese officials repeatedly told me the releases were part of a “special arrangement.”)

Chen Ziming had been diagnosed with cancer, heart disease, and Hepatitis C while Wang had been diagnosed with Hepatitis B. Wang Juntao left China immediately after he was released and relocated to New York, where he has lived to the present day, distinguishing himself in both academics and activism. Neither he nor his family were provided with the documentation necessary for granting medical parole.

Chen opted to stay in China. He was imprisoned again in June 1995 but was again released on medical parole in November 1996. He was placed under residential surveillance until his sentence expired in 2002. Chen Ziming passed away in 2014.

Liu served his entire sentence without a sentence reduction. He was released on June 18, 1995. He departed in May 1996 for the United States. He forged a successful business career in technology and finance, working for Bell Labs and Morgan Stanley. Like Wang Juntao, he has remained active in promoting democracy in China.

As recounted in “Operation Yellow Bird,” Hong Kong businessman Lo Hoi-sing (Luo Haixing) was sentenced to five years in prison for trying to get Chen Ziming and Wang Juntao out of China. He was granted early release from Huaiji Prison in western Guangdong Province in 1991, after which he returned to Hong Kong.

My work on these cases established a modus operandi that I have relied on for prisoner interventions to the present day. I submitted prisoner lists to the Chinese government and pressed Chinese officials for responses, met with family members of the imprisoned, informed the US government of my activities and coordinated efforts with the American embassy in Beijing, obtained letters from members of Congress that were forwarded to the Chinese government, held press conferences (including in Beijing), and gave speeches, many in Hong Kong.

Although governments met with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) to press for clemency for political prisoners, what set my work apart was my ability to meet with other key bodies, including the State Council Information Office, the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), and the People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs, as well as the MFA. I met with officials of all these bodies to discuss the Chen Ziming/Wang Juntao case.

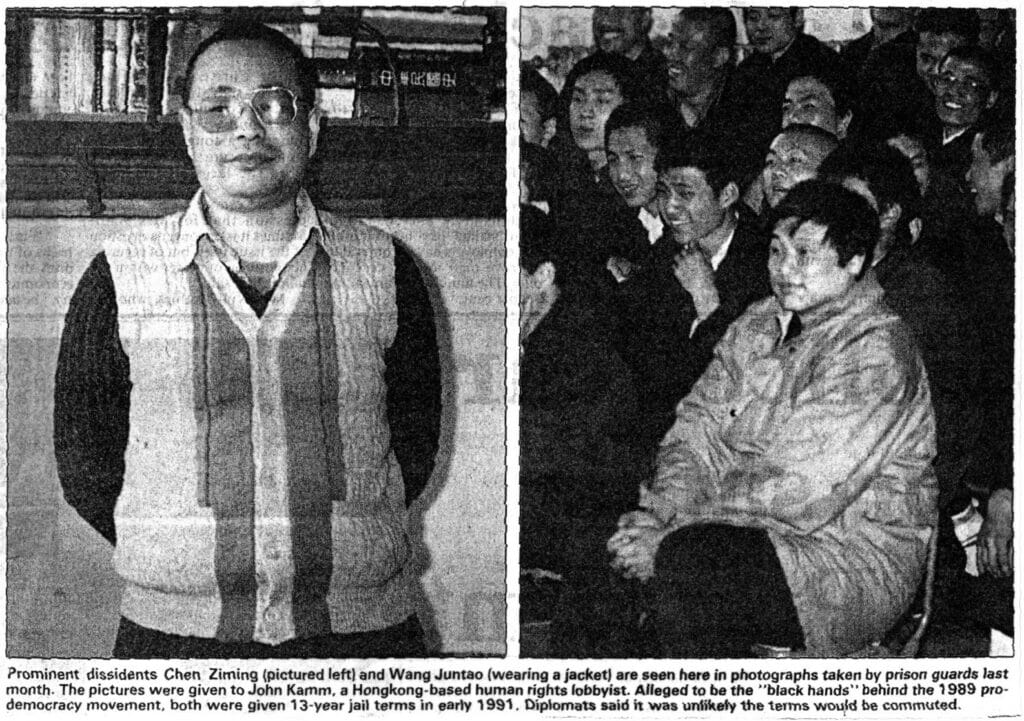

Photographs

On my May 1992 visit to Beijing, I met with Minister Zeng Jianhui of the State Council Information Office (SCIO). We met in his rather rundown office in the Asian Games Village. Zeng handed me three photographs of Wang Juntao and two of Chen Ziming. Wang was shown watching a performance at Yanqing while Chen was photographed in his cell, books stacked high on his bunk bed. Yanqing is near a hospital operated by the MOJ. Zeng told me that Wang was being treated for Hepatitis there but had been returned to his cell. Both Wang and Chen were in four-man cells that were not, at the time of my meeting with Zeng, fully occupied.

I provided the photographs to the media in Beijing. Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post ran the pictures the next day.

Not everyone was happy with my releasing the photographs of Chen Ziming and Wang Juntao. At a congressional hearing held on June 29, 1992, Human Rights Watch (HRW) Washington representative, Mike Jendrzejczyk attacked me for releasing photographs of Liu Gang playing volleyball. HRW had claimed that Liu had had his arm broken. In fact, I hadn’t been given any photographs of Liu, which I pointed out to the congressman running the hearing. Jendrzejczyk’s response was classic: while Kamm may not have released the photos, he could have!

Around the same time, another HRW staff person attacked me in a letter to the Los Angeles Times, implying I was being used by the Chinese government to spread disinformation. In a similar vein, Harry Wu told the San Francisco Chronicle that he had warned me against being used by the Chinese government (in fact, he hadn’t). I ignored these and other attacks on me and my work. As the old saying goes, “Living well is the best revenge.”

Interrogation

On my August 1992 visit to Beijing, I met with Assistant Minister of Public Security Zhu Entao at his headquarters near Tiananmen Square. (Zhu’s nickname was China’s 007). He gave details of the interrogation of Hou Xiaotian, Wang Juntao’s wife at the time. The interrogation lasted four days. “At first she was very uncooperative,” Zhu related, “but her attitude changed as time went on, so we released her. We promised to look into her complaints about her husband’s treatment.” After her release from public security detention, the police kept her under surveillance.

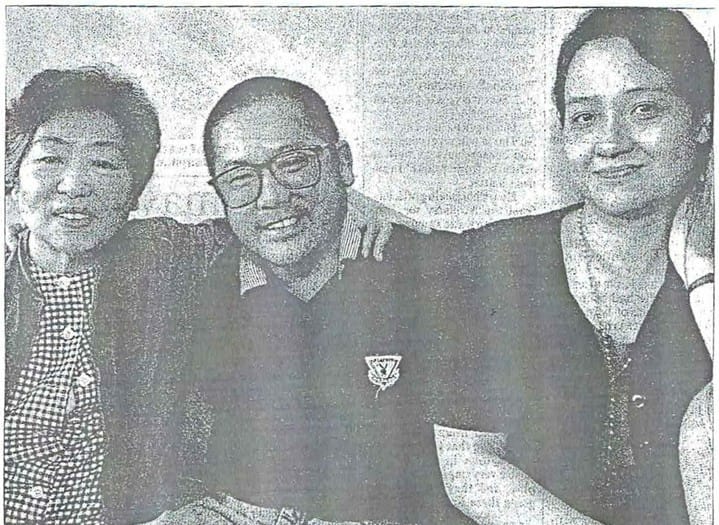

On August 25, 1992, I was hosted by Zhou Jue, Vice Minister of the SCIO and former Chinese Ambassador to France, to dinner. Zhou told me that Wang Juntao had staged a hunger strike but that he was now eating normally. A photograph of Wang Juntao eating with his relatives the night after his release was circulated by Beijing.

The following evening, August 26, 1992, I hosted a banquet for most of the senior officials I worked with on prisoners including Yang Jiechi (MFA), Zhou Jue (SCIO), Zhu Entao (PSM), and Li Yucheng (SPC). In light of the looming US presidential election, I stressed the importance of releasing Wang Juntao and Chen Ziming and other high-priority prisoners.

“Special Privileges”

On my March 1993 visit to Beijing, I met with Mr. Wang Mingdi, director of the MOJ’s Prison Administration Department, at the MOJ’s dilapidated office building on a dusty side road off the main highway to the old airport. (Across from the office gate, a pool table occupied the street. Players were muscular young men wearing police fatigues.) Wang told me that Chen Ziming had been granted “special privileges” so that he could study for his doctorate. Wang Mingdi listed them as “better lighting, more paper, more books.” I relayed Chen’s family’s concern that he was sharing his cell with common criminals and that he was not being treated for a skin disorder.

Clinton, Wang, Chen

In my meeting with Wang Mingdi on my June 1994 trip, shortly after Chen and Wang had been released, he spoke sarcastically about Wang Juntao’s activities in the United States: “When he was in jail, you kept telling us how seriously ill he was. We spent lots of money — more than RMBl00,000 — on medical treatment for Wang Juntao. He wouldn’t have been able to travel to the United States in such good shape had we not treated him so well. But now I read that he is undertaking all kinds of strenuous activities — traveling here and there for speeches and meetings. I’m tempted to ask you Americans: if Wang Juntao’s medical situation is so serious, aren’t you afraid you’ll endanger his health by arranging so many programs for him?” Wang Mingdi did not characterize Wang Juntao’s activities as illegal or as representing violations of the terms of his parole.

On the same trip I met with Ambassador Zhang Wenpu, Vice President of the People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs, a top America watcher who played a key role in what he called the “Wang Juntao/Chen Ziming deal for MFN.”

An agitated Zhang Wenpu had this to say: “I and many other Chinese officials find it abhorrent for China to trade prisoner releases for concessions from foreign powers.” He went on. “We released two of the five names on the State Department’s final list. Do people in the West appreciate that President Clinton raised both Wang Juntao and Chen Ziming’s names during his meeting with President Jiang Zemin in Seattle, and that subsequent to their names being raised, both were released? Is the significance of this understood? I have been in the Chinese government for my entire working career, and I think this is quite extraordinary.”

A year after my June 1994 trip to Beijing, I moved with my family to San Francisco, where I have stayed to the present day. With close friends, I established Dui Hua in 1999. The foundation continues to intervene on behalf of political and religious prisoners in China, using the modus operandi established during the work on the Wang Juntao and Chen Ziming cases in the early 1990s.