<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

Download this story as PDF

Listen to Dragon Years: 2000 podcast episode.

In my two years in leadership positions at the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong (AmCham HK) – 1989 when I was First Vice President and 1990 when I was President – I focused on maintaining and expanding trade with Communist countries. I led the fight to maintain China’s Most Favored Nation (MFN) trading status, testifying to Congress three times when I was president, and many more times in ensuing years. I coupled my support for China’s MFN with advocacy on behalf of political prisoners.

In June 1989, two weeks after the killings in Tiananmen Square, I led a small AmCham HK delegation to Laos, then firmly in Vietnam’s orbit. Then in September 1990, I led another small delegation to Mongolia, which had just begun the transition to democracy after decades in the Soviet Union’s orbit. According to Joseph Lake, the first resident US ambassador to Mongolia, ours was the first US trade mission to that landlocked nation. Although AmCham HK was invited to Myanmar (formerly known as Burma) by the ruling junta that had seized power in a coup, the visit didn’t take place due to government bureaucratic incompetence, and because of the junta’s hostility towards the US ambassador, Burt Levin, a former consul general in Hong Kong and friend of AmCham.

Despite setbacks, I still hoped to visit Myanmar before the end of my tenure as AmCham president. I also hoped to visit Vietnam. Neither trip came to pass.

Beijing

Prior to travelling to Mongolia, I spent five days in Beijing, from September 6 to10, 1990, to work on joint venture opportunities, especially one in Qingdao to produce sodium silicate. This was to be the first 50:50 venture between the United States and China in the chemical industry. At the last minute, however, my employer walked away from the opportunity. Not long after this decision, I resigned from the company.

On September 7, I met with Li Hou, Secretary General and Deputy Director-General of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office under the State Council. Li had participated in both the Sino-British negotiations on the transfer of Hong Kong to China and the Sino-Portuguese negotiations on the transfer of Macau to China. As such, Li was the most experienced and knowledgeable Chinese official dealing with the two territories.

Our discussions centered around developments in Congress on China’s MFN and other matters, notably a bill that would offer protection to Chinese students in the United States. Li listened intently and took copious notes on what I said. As he didn’t seem so interested in the legislation offering visa protection to Chinese students, I took as a sign that he did not particularly care about the subject. After the meeting, AmCham issued a press statement on our meeting saying Li wasn’t opposed to the bill Li took exception to that interpretation and sent me a letter after I returned to Hong Kong clarifying his position.

With what time I had, I went book shopping, had breakfast with the American Chamber of Commerce in Beijing, attended an American embassy reception in our honor, and spent time with the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade, AmCham’s longtime hosts in China. On September 9, 1990, I had dinner with members of the delegation at a well-regarded Japanese restaurant in Beijing.

Flight to Ulaanbaatar

On September 10, 1990, I was joined at Beijing airport by six AmCham members and the American Consul General in Hong Kong, Richard Williams, for the 90-minute flight to Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia. Ambassador Williams had served as the first American ambassador to Mongolia but unlike his successor he was never resident in the country.

We were greeted at the airport by our hosts, the Ministry of Trade and Cooperation, the Mongolian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and the US Embassy. We were taken to the guest house on the grounds of the presidential palace, where we’d be staying for our four-day visit to the country,

We glimpsed a small group of individuals in traditional Mongolian dress sitting by the gate. I learned that they were the remnants of a group of hunger strikers that had gathered to protest the former pro-Soviet Mongolian government.

We ventured out to see the sites, returning for dinner at the guest house. Some of us wanted to try local fish, but were told that Mongolians don’t eat fish, believing that fish embodied spirits. I resolved to try to order fish at a future meal. In the meantime, we would enjoy dishes of mutton served in a variety of ways.

We had an opportunity to discuss Mongolia’s economy with staff and management of the guest house. The Soviet Union had stopped assisting Mongolia, resulting in a serious economic crisis. A member of the staff remarked that the principal indicator of the economy’s strength was the size of the coal reserves. At the time of our visit, Ulaanbaatar had sufficient supplies of coal to run its power plant for just two days.

Sites of Ulaanbaatar

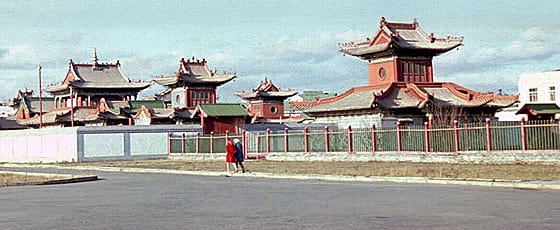

Choijin Lama Temple

Our first stop was the Temple of the Choijin Lama. Our guide, a lively young woman with excellent English, told us that this lama was the third ranking lama in the hierarchy of Lamaist Buddhism after the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama.

We were unable to enter the palace. Buddhism had been repressed in Mongolia beginning in the 1930s; hundreds of temples were destroyed, thousands of monks subjected to forced labor, and thousands were sentenced to death. No one was home to receive us.

With the advent of democracy in 1990, the year of our visit to Ulaanbaatar, Buddhism gradually returned to Mongolia, where an estimated 50 percent of the population today are Buddhists.

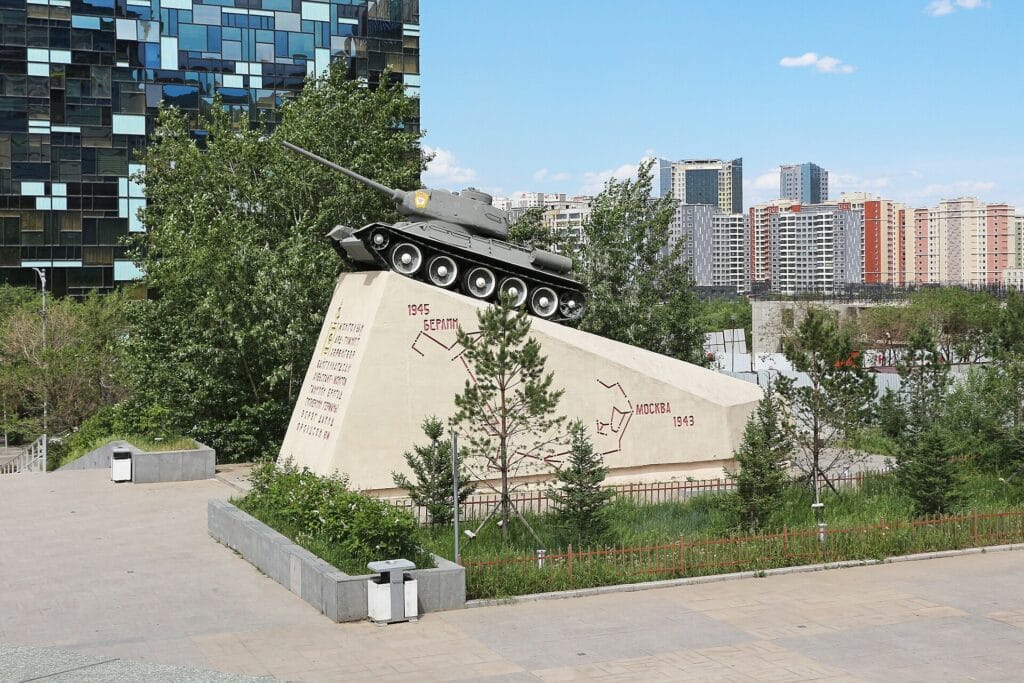

Monument to the Revolutionary Tank Division

Nearby the palace was another reminder of Soviet influence. Mounted atop a striking pedestal was a Soviet T-34 tank used by the 112th Revolutionary Mongolian Tank Division in its battle against German troops during World War Two. The refurbished structure is now known as the Zaisan Memorial.

The 112th Revolutionary Mongolian Tank Division suffered huge casualties but ultimately scored victories against the Nazi invaders, notably at the Battle of Moscow. It was among the most decorated units that fought the Wehrmacht.

Toys Exhibition

On September 11, we visited an exhibition of Mongolian toys and puzzles, now known as International Intellectual and Puzzle Museum. The Mongolian people are renowned for puzzle creation and solution. The exhibition featured thousands of puzzles and toys, some of which had never been solved.

Meetings

Briefing by Ambassador Lake

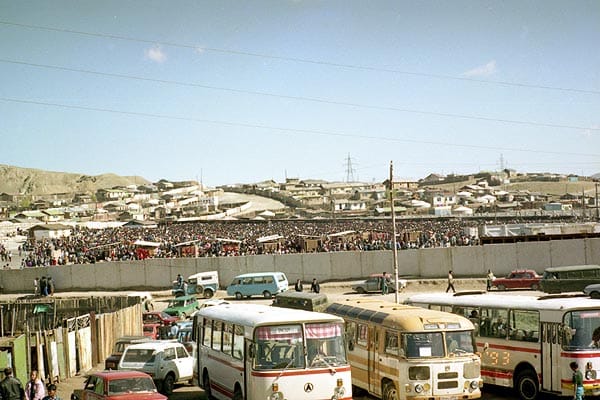

The delegation’s meetings kicked off with a briefing at the guest house by Ambassador Joseph Lake on September 11, 1990. Ambassador Lake went over the history of the Mongolian Revolution from early demonstrations, hunger strikes, and protests that began in late 1989 with a few hundred demonstrators and eventually swelled to a crowd of 100,000. A milestone in the transition to democracy took place two days before our visit when the Prime Minister, his deputies, cabinet members, and members of parliament were elected.

Mongolian Chamber of Commerce and Industry

We spent most of the day with our host, the Mongolian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (MCCI). We started with a round-table discussion before a large audience of businesspeople and officials. I delivered prepared remarks in which I urged Mongolians to have courage as they embarked on the path of reform.

After lunch we met with the State Bank, the Union of Cooperatives, and Mongolimpex, the largest foreign trade corporation in Mongolia. We finished the day with a reception and dinner hosted by MCCI.

State Commission for Technology

We started September 12with a meeting with the State Commission of Technology. At that meeting we were introduced to Mongolia’s traditional drink: fermented mare’s milk, also known as airag. I did not like the taste, but Dick Williams quaffed a full glass without hesitation.

The delegation was hosted to lunch in a ger—called a yurt in Central Asia and Russia— by the Deputy Minister of Trade after which we headed to the presidential palace.

Dashin Byambasiin

Our hour-long meeting with Prime Minister Byambasiin centered on plans to reform the economy, the goal of which was to sharply reduce dependence on the Soviet Union. The key features of the reform were the privatization of state enterprises, establishment of a stock exchange, full convertibility of the tugrik (Mongolia’s currency), price reform to achieve all prices set by the market, private land ownership, and an open-door policy to attract foreign investment.

The prime minister disclosed that talks were underway with the Soviet Union to value the debt that Mongolia owed to the communist country. The Soviets wanted to use a rate of two rubles to the tugrik, while the Mongolians wanted to use 10 rubles to the tugrik. Despite this sizable difference, the two sides had agreed to delay payments until 1995.

Business meetings

After the meeting with the prime minister, the delegation broke up for discussions with Mongolian government bodies and corporations to discuss business opportunities. I had convinced my employer to underwrite the cost of my trip to Ulaanbaatar to explore what trade and investment might be done in this new market.

I met with the Chemical Institute. I was told that there was not a single chemical plant in the country. I wondered if there was interest in importing technology for producing caustic soda but encountered resistance due to concern over pollution. I was told that the United Nations had concluded that Mongolia was the only country in the world where one could dip a cup into a river and drink the water without fear of contamination from pollutants.

I met with representatives of Arimpex to gauge interest in purchasing chrome chemicals for the tanning industry. Sodim bichromate was purchased in small quantities from Japanese trading companies. Transport costs were prohibitive and made selling chrome chemicals from American plants impossible.

Farewell Reception and Dinner

Our trip ended with a reception and dinner at the guest house. We were served mutton and salmon, which I finally had a chance to eat. It was delicious.

We also were able to sample Mongolian drinks, including Chinggis Khan vodka and suutei tsai, the Mongolian milk tea.

By Train to Beijing

We arrived at the train station early on September 13 to secure our cabins for the long train ride back to Beijing. While the once-weekly flight to Ulaanbaatar took 90 minutes, the overnight train ride back to Beijing would take 30 hours. The train departed promptly at 9:30 AM.

Our delegation took two cabins and shared one of them with a rough-looking Japanese explorer who had been trekking around Mongolia for several weeks. He sustained himself with a leg of cured mutton. He took out a knife and offered us slices.

We ate all the meals on the train. Nothing special, standard railway fare.

On our way out of Ulaanbaatar, we passed the Ger District. As far as the eye could see, ger populated the landscape. It was mid-September, but the air had turned cold. Smoke from coal burning stoves filled the sky. Although there was no water pollution in Mongolia, air pollution was a different matter.

Heading south, the train stopped in Choyr and Sainshand, both provincial capitals, before arriving at Zamyn-Uud, a town on the border with Inner Mongolia. At the railway towns of Choyr and Sainshand we got off the train to check out the environs. We were mobbed by local children, curious to see foreigners traveling by rail in Mongolia. The daily arrival of the train of the Trans Mongolian Railway was a big event in those parts.

At Zamyn-Uud, we got off the train with our valuables and went into the reception room at the station. There we went had our passports stamped before we walked to Erinhot on the Chinese side of the border. Our passports were checked and stamped with exit and entry chops, respectively. AmCham delegates all had Chinese visas.

While we underwent exit and entry formalities, the Mongolian railcars were lifted off their bogies by huge cranes and moved to the Chinese side of the border, where they were placed on new bogies. Railroads operated on different gauges in Mongolia and China, a move designed to forestall invasion from the Soviet Union.

The train passed by eight cities in Inner Mongolia and Hebei before arriving in Beijing at 3:30 PM on September 14. Some of us returned to Hong Kong on Cathay flight 329 the next day.

Inner Mongolia

Aside from taking steps to forestall a Soviet invasion, the difference in rail gauges served another purpose. Inability to travel between Mongolia and Inner Mongolia reduced interaction between Mongolians on both sides of the border. This in turn engendered resentment against China among Mongolians.

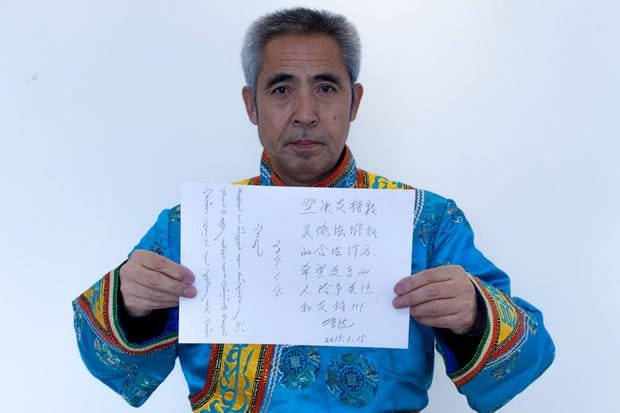

Over time, the Chinese government began encountering an indigenous independence movement in Inner Mongolia. This movement arose as a response to measures to seize grazing pastures and discourage the use of the Mongolian language as well as the practice of Mongolian customs, much as language and customs have been curtailed in Tibet and Xinjiang.

Dissidents were arrested and sentenced to long terms. The most famous was Hada, a Mongolian entrepreneur and member of the Southern Mongolian Democracy Alliance who was detained in December 1995 and subsequently sentenced to 15 years in prison and four years deprivation of political rights for the crime of counterrevolution. During the latter period Hada could not receive visitors. I placed his names on 36 lists and received 32 responses, a high list-to-response ratio, but my advocacy was for nought. He served his entire sentence without reduction or parole.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.