<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

Listen to Dragon Years: 2000 podcast episode.

L

ess than four years after the events of May and June 1989, Beijing applied, in 1993, to host the 2000 Summer Olympics. It lost the bid by two votes to Sydney. One of the votes was cast by the US representative on the Olympic Committee.

The loss to Sydney was a great disappointment for China. A senior official with whom I met to discuss human rights, including political prisoners, told me that the US had created a great deal of good will among the Chinese people and Chinese officials alike over its criticism of China’s human rights but, despite this, its decision to maintain China’s trade status. “That goodwill has been lost.” That was the beginning of the decline in the United States’ popularity in China. It has never recovered.

George W. Bush and Sandy Randt

Amidst this backdrop of Chinese disappointment, George W. Bush was elected the 43rd president of the United States in November 2000. His election was challenged by his opponent Al Gore, touching off a three-week battle that was eventually settled by the Supreme Court.

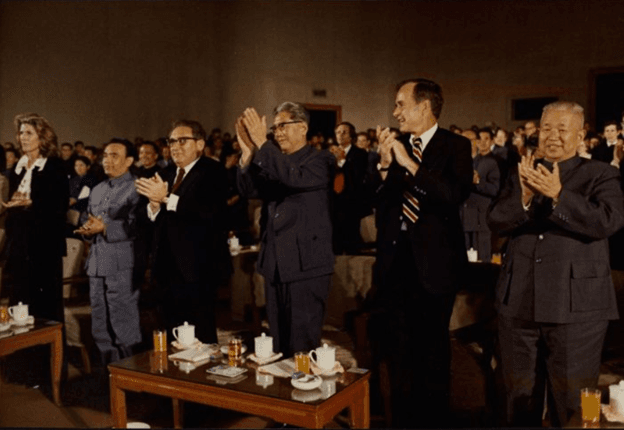

George W. Bush’s father was George H. W. Bush. The senior Bush served as the second US envoy to Beijing, serving as the head of the US Liaison Office (USLO) in Beijing between 1974 to 1975. He went on to become the 41st president of the United States. George W. Bush and his sister spent time in Beijing while his father was head of the USLO; he became familiar with the country and its senior officials long before he became president.

George W. Bush took office in January 2001. Not long afterwards, he nominated his friend and classmate Clark (Sandy) Randt as the US Ambassador to Beijing. He was confirmed by the Senate in July 2001 and sworn in by Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage. I was honored to attend his swearing in. He presented his credentials in Beijing on July 28, 2001.

Sandy Randt had spent 18 years in Hong Kong. He was an attorney, a recognized expert in Chinese law, and a keen observer of developments in China. He had served as a commercial attaché and First Secretary at the US embassy in Beijing from 1982 to 1984. He was also an officer of the American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) while I was president of the chamber. Our friendship predated his time as an AmCham officer by several decades. We were, and remain, close friends, as were our families. Our children grew up together. Our friendship proved to be decisive for my human rights work in China.

Sandy Randt, who was to become the longest serving US ambassador to China, spoke excellent Chinese, but may not have been as fluent as other US ambassadors to the country, two of whom were born in China. Nor did he have the deep knowledge of the ins and outs of how US state and federal governments work as other ambassadors, two of whom served in the Senate and two of whom were elected governors. Nor was he as well versed in matters of national security as other US ambassadors, one of whom had served in the CIA.

Yet Sandy Randt proved to be more effective than any other ambassador who held the position since the countries normalized relations in 1979. He was able to pick up the phone and speak directly to the president of the United States without having to go through layers of bureaucrats. For this reason, he was respected and even feared by senior Chinese officials.

Third Time Lucky

A little over a month after George W. Bush was sworn in as president in 2001, China once again put in a bid to host an Olympics, this time for the 2008 Summer Games to be held in Beijing. Its application was considered by the Olympic Committee in July and was accepted on the third ballot. The Chinese government and the Chinese people were overjoyed.

To win the right to host the 2008 Summer Olympics, the Chinese government made a number of commitments. It is said to have promised to stop parading offenders who were sentenced to death, and to stop executing them in public. It committed to an unprecedented degree of openness, allowing free access by media to different parts of the country and to its own citizens for unsupervised interviews, and to lifting the blocking of the websites of human rights groups.

Beijing failed to live up to its promises. Parading of those condemned to death continued, as did public executions, albeit in parts of the country outside major urban areas. The websites of Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch were unblocked, but others continued to be blocked, including the website of Dui Hua. I protested to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, to no avail.

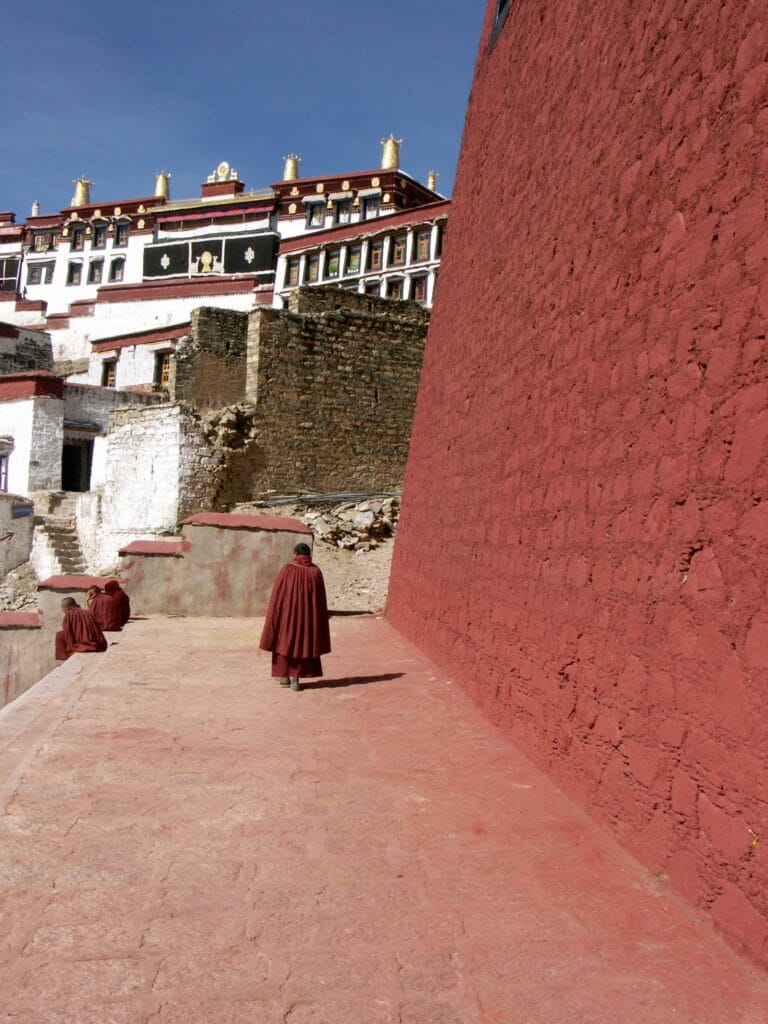

Tibet Erupts

On March 10, 2008, five months before the Games were set to begin, protests broke out in Tibet and other Tibetan areas of the country. By the Chinese government’s count, demonstrations, some violent, occurred in 150 locations in Tibet and Tibetan areas of other provinces, from March 10 to March 25, 2008. Human rights groups’ estimates of the number of demonstrations that occurred after March 10 were much higher.

Hundreds of people were killed by protesters and police. Thousands were arrested and thousands more remain unaccounted for. Buildings and critical infrastructure were destroyed. The Tibetan uprising prompted increased attention to China’s human rights in general, and political prisoners in particular.

In response to the crisis, Dui Hua proposed an Olympics Special Pardon for political prisoners in a speech I delivered in Hong Kong on March 29, 2008. The foundation focused on two long-suffering groups: those still in jail for their participation in the June 4 protests, and counterrevolutionaries. Counterrevolution had been removed from the Criminal Law in 1997.

Special pardons are provided for under Chinese law. Dui Hua followed up the Hong Kong speech with a letter to Wu Bangguo, chairman of the National People’s Congress (NPC), the body that grants special pardons.

The proposal was received favorably by Chinese officials, relatives of Chinese prisoners, and foreign human rights groups. Unfortunately, the NPC failed to act, but several well-known prisoners were granted a measure of clemency, including the Hong Kong journalist Ching Cheong (程翔), who was released and allowed to return to Hong Kong, and American citizen Jude Shao, who was granted parole but forced to remain in China. Jude Shao had been visited by US Ambassador Randt in the Shanghai prison where he was incarcerated.

Tragically, one Chinese citizen who should have received clemency did not. Wo Weihan (沃维汉), a member of the small Daur minority residing in Heilongjiang Province, was executed on November 28, 2008, for espionage. The charges against him were ludicrous and violated the policy of granting leniency to members of ethnic minorities. I had worked hard on his case, having gotten to know his daughters, both of whom are Austrian citizens. I denounced the execution in print and in face-to-face meetings with Chinese officials.

In 2015 and 2019, President Xi Jinping proposed special pardons that the NPC went on to grant. In all, 47,000 prisoners were pardoned. Principal beneficiaries of the pardon were juveniles and elderly prisoners, two groups that Dui Hua’s advocacy work has focused on.

I supported the decision to grant the 2008 games to China, though other commentators and human rights activists opposed. One journalist likened granting the games to Beijing to the decision to hold the 1936 games in Nazi Germany. The journalist criticized Dui Hua’s support for the Beijing Olympics. This was especially hurtful to me. Growing up, I knew Holocaust survivors, and my uncle had been an investigator at the Nuremburg trials of Nazi war criminals.

Sichuan Earthquake

On May 12, 2008 – three months before the Games were set to begin — a massive earthquake measuring 8.0 on the Richter scale struck Sichuan Province near the capital city of Chengdu. An estimated 90,000 people were killed, thousands more injured, and countless buildings destroyed. Journalists and all unessential personnel were ordered to leave Sichuan.

On June 10, 2008, activist Huang Qi (黄琦)was detained in Chengdu on suspicion of trafficking in state secrets related to his accusations of shoddy construction that resulted in the collapse of buildings after the earthquake. He was subsequently sentenced to three years in prison. Huang continued his activism after his release. He is currently serving a 12-year sentence for endangering state security, his third imprisonment.

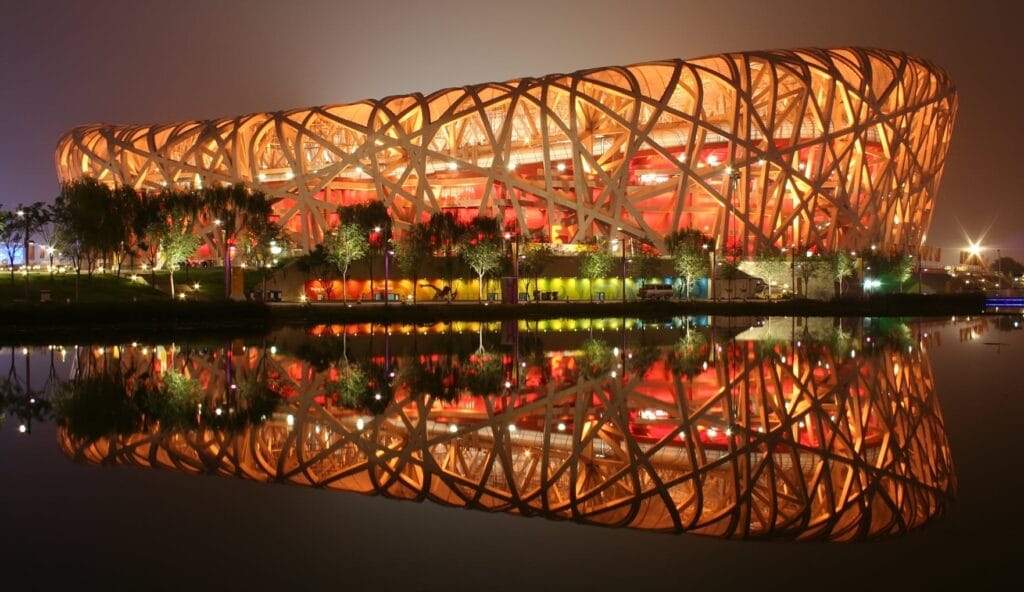

Ai Weiwei (艾未未), a famous artist who was a design consultant for the stunning National Stadium (colloquially known as the Bird’s Nest and built specifically for the Games), was impacted by the quake. In April 2011, he was detained at Beijing Airport and subsequently placed under residential surveillance in a designated location. Although Ai was later released on bail some 80 days later, he was confined to his Beijing home, akin to house arrest. He was accused of tax evasion. Many suspected that the real reason he was detained was his vocal support for victims of the Sichuan earthquake, many of them children, and the work of other activists.

The Bird’s Nest was rarely used after the Games, as were other structures erected for the occasion. They became White Elephants. No one knows how much China spent on the Games, but it was doubtless a large sum.

As for Dui Hua, the impact of the quake was immediate. We had been planning our first juvenile justice exchange with Chinese judges to take place in the United States in June. I insisted that the program be postponed, and our Chinese partners eventually agreed. Instead, they arrived in October and visited courts, carceral facilities, and other sites in Chicago, Washington D.C., Maryland, and San Francisco. The program was a success. It opened the door to Dui Hua’s cooperation with China’s Supreme People’s Court in the field of juvenile justice, an important area of human rights.

Before the earthquake related crackdowns, other human rights activists were being impacted by the Games. Hu Jia (胡佳), a prominent dissident sentenced to prison for criticizing the Chinese government’s failure to improve human rights before the Games, was sentenced to three and a half years in prison. He was serving the sentence while the Games took place. His wife at the time, Zeng Jinyan, had supported the proposal to grant an Olympics Special Pardon.

Hu Jia was nominated for the 2008 Nobel Peace Prize. The Beijing Games were very much on the minds of those who put him forward. He was the odds-on favorite to be chosen as the 2008 laureate, but in the end the Nobel Committee chose someone else. Two years later, Liu Xiaobo (刘晓波) became the first Chinese to be chosen by the committee for the peace prize. Liu died in 2017 because of poor treatment while serving his sentence.

Torch Run

In keeping with tradition, an Olympic torch relay began in Greece, and ended in the city where the games would be held, in 2008, Beijing. The torch passed through six continents and covered 85,000 miles before arriving in Beijing. The relay lasted 129 days and is the longest distance covered of the modem games.

The relay was marred by protests over Tibet and human rights abuses, which disrupted the relay in London and Paris. Violence occurred in Nepal, home to a large Tibetan population.

China learned lessons from these protests. I was in San Francisco when the relay took place and witnessed changes. With the help of the San Francisco Police Department, the route was changed to the outskirts of the city. The Chinese consulate arranged for counter protesters from the Bay Area’s large ethnic Chinese community to show up. Buses filled with students were laid on. The result of this effort was film footage used in a propaganda film to give the impression that Americans enthusiastically welcomed the torch relay, and by extension, the holding of the Games in Beijing.

The Games Begin

Shortly after the torch arrived in Beijing, the opening ceremony was held with a stunning display of fireworks and music.

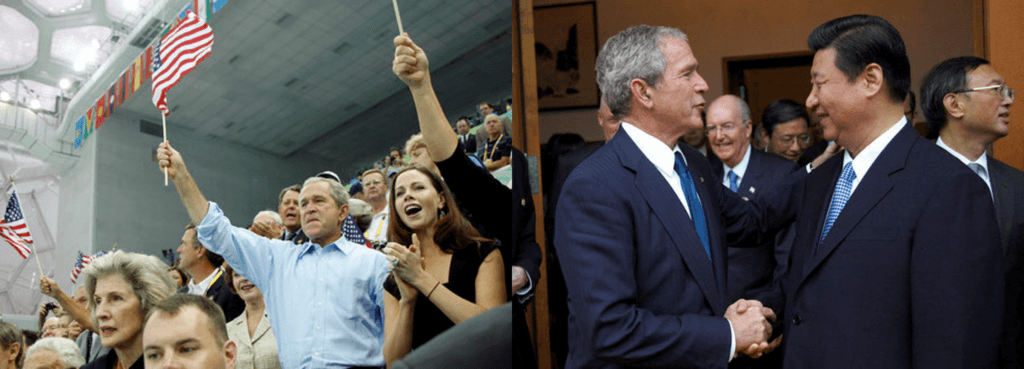

President Bush had been urged by European leaders to join them in boycotting the opening ceremony on account of China’s human rights record. Bush declined to do so and wound up attending the opening ceremony. He stuck to the position that politics and sports should not be mixed.

While in Beijing, President George W. Bush presided over the opening of the new US embassy in Beijing with Sandy Randt. He was joined by his father, mother, and Henry Kissinger.

The day after the glittering opening ceremony, tragedy struck. A US citizen, the father of an Olympian who played on the 2004 volleyball team, was knifed to death on the Drum Tower. His guide was also murdered, and the Olympian’s mother was badly injured trying to protect her husband. Their assailant jumped to his death from the Drum Tower, sparing him from execution.

Results of the Games

China won the most gold medals at the 2008 Summer Olympics, and the United States won the most medals overall. But the games did little to improve China’s international image thanks largely to its brutal crackdown in Tibet, its detentions of Chinese citizens for the peaceful expression of their views, and its failure to honor commitments to greater openness and more restraints on capital punishment.

The success of the games did not help Chinese President Hu Jintao’s reputation either. He left office in 2012, widely seen as a weak leader. He was humiliated at the closing session of the National People’s Congress in October 2023 when documents were snatched from his hands, and he was denied the opportunity to speak. He was led off the stage a broken old man. He reappeared at the funeral of Jiang Zemin in December 2023 but has not been seen in public since.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.