<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

Listen to Dragon Years: 2000 podcast episode.

A

s my tenure as President of the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong (AmCham) drew to a close in 1990, I began speaking out on Hong Kong issues and political prisoners in China. In remarks delivered to the Australian Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong, I called for the release of prisoners detained during the June 1989 protests in Beijing. In a speech to the National Committee on US-China Relations in New York in December, I called for legislation to protect the people of Hong Kong as well as US interests in the colony.

In attendance at the Australian Chamber event was an AmCham staff member. She quickly told the incoming leadership what I had said. Retribution was swift. I was no longer invited to American consulate briefings and meetings with visiting members of Congress, many of whom I got to know during my trips to Washington between 1990 and 1992, when I testified six times before committees of the House of Representatives and Senate.

In 1991, my successor as AmCham leader sent me a letter on AmCham stationary asking me to make sure the press did not mention my tenure as chamber president when writing about me. In the letter, he claimed that a big AmCham member was threatening to leave the body unless the press stopped mentioning my leadership when reporting on my human rights work. (He also offered the services of his public relations firm.) At the AmCham dinner to kick off 1991, he refused to say my name or acknowledge my work on a raft of issues I had dealt with on behalf of the business community, a snub that did not go unnoticed by Hong Kong officials in attendance. Not all AmCham directors supported what my successor did, but several backed him up.

“Pay Me with Information on Prisoners”

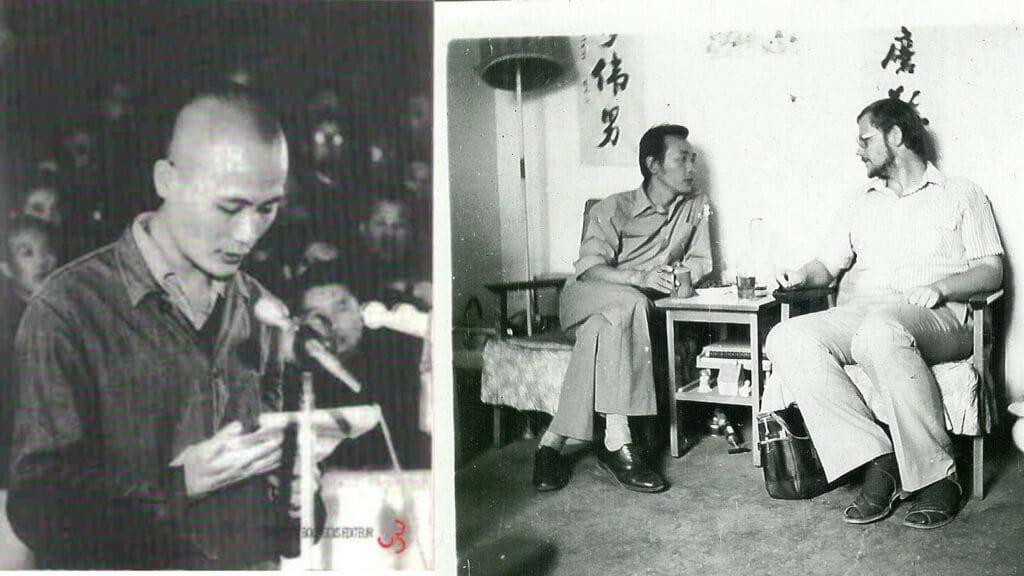

Unlike the American business community and other hostile businesspeople, Chinese officials were friendly. In January 1991, a party official based in Guangzhou came to see me in Hong Kong. This meeting led to a visit to Guangzhou in March during which I handed over my first list of ten prisoners, individuals detained during the Democracy Wall movement and the June 4, 1989 protests.

In April I was invited to come to the office of the Xinhua News Agency in Wanchai. Xinhua acted as the de facto Chinese embassy in the colony. Upon arrival I was ushered into a room where two officials in charge of economic and trade matters were awaiting. After thanking me for my work on Most Favored Nation (MFN), one of them, Mr. Wang made me an unusual offer.

“Would you like to do some business with China?” he asked. “We can grant you exclusive agencies for products much in demand in Hong Kong, including silk.” Agencies oversee distributors and as such do very little work. In effect, all they do is collect commissions. I was being offered a sweetheart deal to compensate me for my work on MFN.

I politely rebuffed the official. I cautioned them that the threat to MFN was not over and was likely to come up again for years to come. “I want to invest in the issue. If you want to pay me, pay me with information on prisoners,” I said.

They were taken aback by my response. “Who do you have in mind?” I brought up the name of an activist detained after June 4. Mr. Wang jotted down his name.

Not long afterwards, I received a fax with information on the activist, sent from a Beijing number that I did not recognize. This turned out to be an office under the State Council Information Office (SCIO) whose leaders would come to be known, collectively, by the pseudonym Bai Li.

Bai Li

Bai Li was a principal source of information on prisoners from April 1991 to April 1995. Bai Li was by no means the only source of information. I also received information on prisoners from the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), the Ministry of Public Security (MPS), the Supreme People’s Court, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, and the Religious Affairs Bureau, but Bai Li was, on balance, the most important source of information on Chinese political prisoners during those four years.

In all, the Bai Li channel provided information on more than 100 Chinese prisoners, most of whom were serving sentences for counterrevolution, a crime removed from the Criminal Law in 1997. Many of those prisoners were released early from prison after my intervention.

Information from Bai Li was conveyed by fax to my office in Hong Kong or handed over in person at Bai Li’s office, a run-down structure on the outskirts of Beijing with furniture held together by masking tape. Initially, meetings with Bai Li were arranged by my host in Beijing, the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT). Eventually, I was able to set up the meetings directly by myself, by fax or phone.

Which Prisoners Would Make a Difference?

On one occasion, I hosted a banquet for SCIO and other ministries at a Beijing hotel. Officials of both the justice ministry and the public security ministry were in attendance, a rare occurrence as there was bad blood between the two entities. (MPS used to oversee all prisons in China but in 1980 prisons were put under the administration of MOJ, with one exception, the notorious Qincheng Prison in Beijing.)

At the banquet in Beijing, I was asked which prisoners, if released, would make a difference in Washington. I replied that the release of Catholic clergy would make a difference, pointing out that 40 percent of members of Congress were Catholics. Soon thereafter, Catholic bishops and other clergy began to be released.

On another occasion, I was sitting in the back seat of a car with Bai Li. He was pleased with the result of the Catholic releases and asked who else should be released. I replied that no Democracy Wall prisoners, a group that emerged in the late 1970s that included Wei Jingsheng (魏京生) and Xu Wenli (徐文立), had ever been released early from prison. Releases began in 1992.

Information from Bai Li: A Sampling

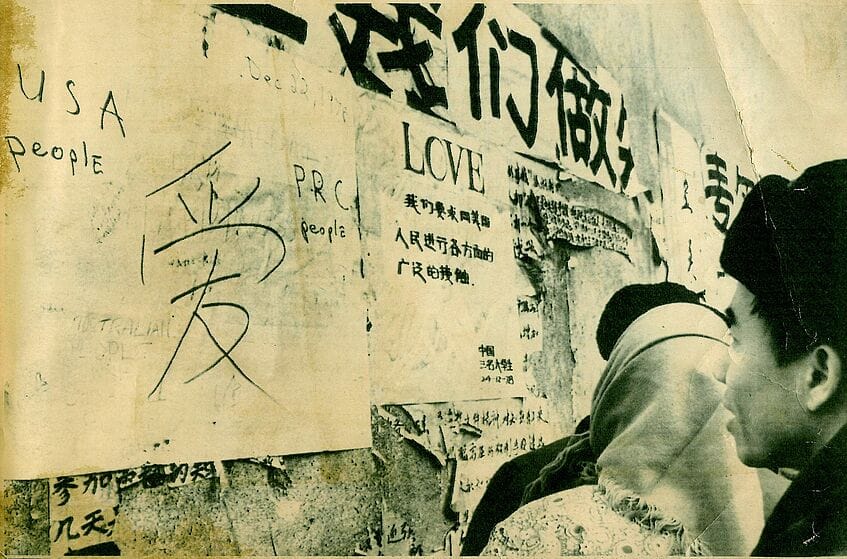

June 4th Prisoners in Qingdao

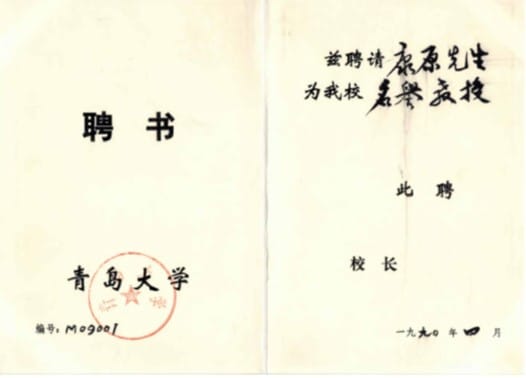

In 1990 and 1991, I made three business trips to Qingdao, a port city in Shandong Province with deep ties to the United States. (Jimmy Carter was based at the US navy base in Qingdao during World War II.) On one of the visits, I spoke to the students and faculty of Qingdao University, where I was made an honorary professor. During a later visit, I spoke to a faculty member and asked her to help a political prisoner, whose family she knew.

Shandong Province courts gave the longest prison sentences to June 4 prisoners, and they had done so sooner than courts in any other province. Two protesters were reportedly executed in Jinan, capital of Shandong Province. Two of the longest sentences were given to two young men who were sent to Shandong Number Three Prison in Weifang to serve their 18-year sentences. In those days, political prisoners in Shandong were sent to Shandong Number Three Prison where they were all housed in the same cell block.

I continued to advocate for the Shandong prisoners in my meetings and correspondence with the Chinese government in the 1990s, including in 1999, the year I set up Dui Hua. In March 1999 I visited Qingdao on business and met with the local branch of the CCPIT, later rebranded as the Qingdao International Chamber of Commerce. I was asked to be their honorary advisor, but I was reluctant to do so. I mentioned that Shandong was known for giving long sentences to June 4 protesters. They asked me for some names, and I handed over a list. In my oral presentation, I focused on six protesters on the list who had been detained in Qingdao following the June 1989 protests. All were released before their sentences expired.

Early in my work, I learned from a good source that one of Qingdao prisoners had neither appealed the judgment to the Shandong High People’s Court nor filed a petition for a retrial with China’s Supreme People’s Court. Bai Li encouraged me to suggest to the family that a petition be filed with the Supreme People’s Court. Eventually, a family member did so. The prisoner was released several years before his sentence expired.

I was given the news of a Shandong prisoner’s release at the end of a visit to Beijing Prison in Daxing Municipality in May 2000. An official from the MOJ who had accompanied me on the visit told me “I have some good news for you,” she said. “The prisoner you care about has just been released.” She was excited and happy to tell me this news.

People of Faith: Catholic Clergy

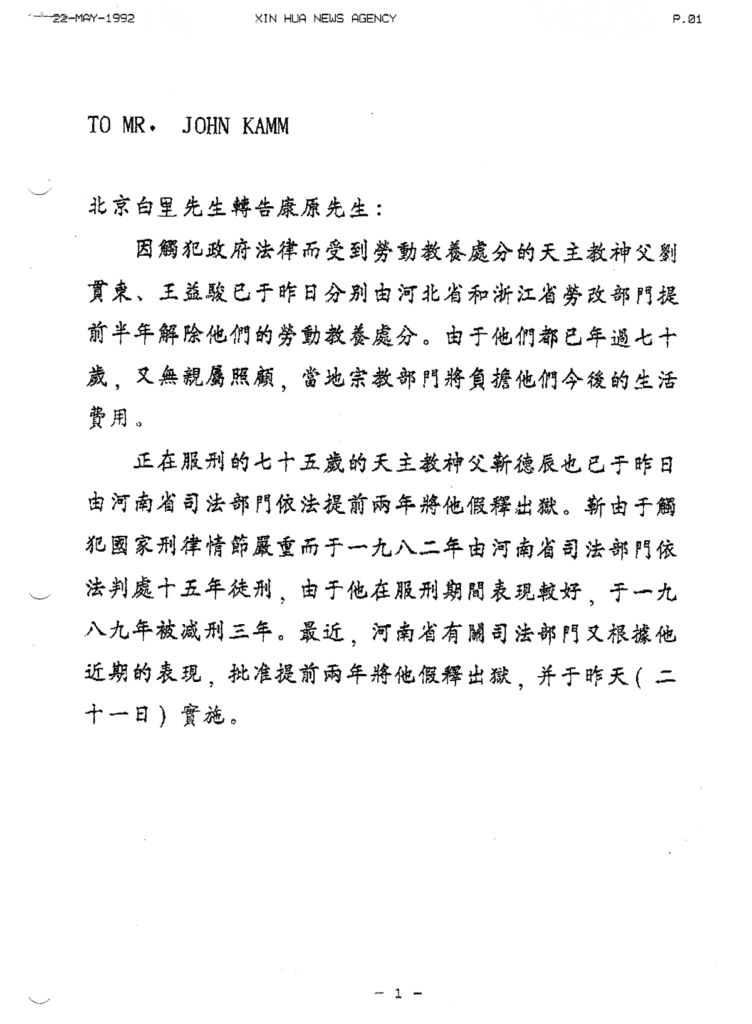

Not long after the banquet in Beijing at which I pushed for the release elderly Catholic clergy, I submitted lists of priests to the Religious Affairs Bureau and the SCIO. On May 26, 1992, I received a fax from Bai Li addressed to my Chinese name Kang Yuan (康原). It was one of the earliest messages from Bai Li and contained information on three priests: Hebei Bishop Peter Liu Guandong (刘冠东), Henan Vicar General Joseph Jin Dechen (靳德辰), and Zhejiang monsignor Francesco Wang Yijun (王益骏). Liu was the elected head of the Chinese Bishops Congress and as such was the leader of the underground Catholic Church in China. Wang Yijun, like Liu Guandong, had spent decades in Chinese prisons for practicing his faith.

TO MR. JOHN KAMM

Relayed communiqué from Mr. Bai Li of Beijing to Mr. Kang Yuan:

Catholic priests Liu Guandong and Wang Yijun, who were sentenced to Reeducation through Labor (RTL) for violating the law, had their punishments lifted yesterday by the Hebei and Zhejiang Provincial RTL organs, respectively, a half a year early. Because they are both more than 70 years old and have no close relatives to care for them, the local religious affairs organs will be responsible for their daily living expenses.

The Catholic priest Jin Decheng, who is seventy-five years old and has been serving a sentence in prison, was paroled yesterday by the Henan Provincial Justice Bureau two years early, in accordance with the law. Jin was sentenced by the Henan judicial organ in 1982 to fifteen years of imprisonment for serious violation of the law. Due to good behavior during incarceration, he was granted a sentence reduction of three years in 1989. Recently, based on his behavior, the relevant judicial organ in Henan approved granting him parole, two years before expiration of the sentence. The parole took effect yesterday (on the 21st of the month).

A response from Bai Li from 1992 on acts of clemency for three Catholic priests, with the English translation. Image credit: Dui Hua

The next year three Catholic prisoners on my lists were released before the end of their terms. Casimir Wang Milu (王弥禄), the underground bishop of Tianshui Diocese in Gansu Province, sometimes called the “Black Bishop of Tianshui” for ordaining priests without the blessing of the pope, Hebei priest Placid Pei Ronggui (裴荣贵), and Henan priest Giuseppe Li Fangchun (李芳春) were released a couple of years before their sentences were set to expire.

The Vatican determined that, on release, Bishop Wang Milu’s mental health had deteriorated to the point that he could no longer carry out his pastoral duties. He was succeeded by his brother, John Wang Ruowang (王若望), as bishop of Tianshui.

In April 1989 – two months before the quelling of pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square – public security officers descended on the Catholic village of Youtong in Hebei Province, injuring hundreds, and killing two villagers. The village priest, Pei Ronggui, was detained and subsequently sentenced to five years in prison for disturbing the social order.

Li Fangchun served two long prison terms for counterrevolution. Father Giancarlo Politi of Hong Kong and I worked hard to secure his early release in early 1993. For the story of Father Li and other Catholic and Protestant clergy released early from prison, please see “Two Good Priests.”

During this period, I asked about 22 Catholics and received written responses for ten of them.

Democracy Wall: Xu Wenli (徐文立), Wang Xizhe (王希哲), Wei Jingsheng (魏京生)

On a visit to Beijing in early 1993, Bai Li asked me a “theoretical” question. “If we want to maximize favorable press coverage in the United States, when should we release a prisoner?” I replied that major media outlets like the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal start putting their issues to bed no later than midnight the day before publication.

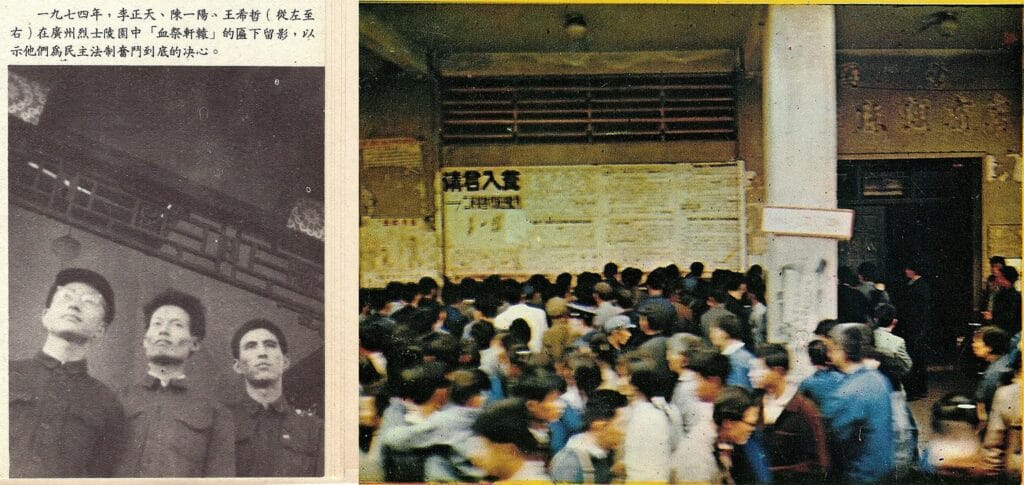

On May 26, 1993, I received a fax from Bai Li. “Xu Wenli will be released from Prison at 10 AM, on May 26, 1993,” two hours before midnight on the East Coast. A few months before Xu Wenli was released, Wang Xizhe, a prominent activist based in Guangzhou, was released from Huaiji Prison in western Guangdong Province. He was serving his second prison sentence, having served time for a big character poster written with Li Zhengtian and two other activists in 1974, a Cultural Revolution group that came to be known as Li Yizhe. Like Xu Wenli, Wang Xizhe now lives in the United States where they have remained active in promoting respect for human rights in China.

I received a fax from Bai Li (misspelled as Bei Li) on September 9, 1993, advising me that Wei Jingsheng had been granted parole. This was surprising as I had been told that the chance of an early release was small due to Wei’s attitude in prison and his passion for arguing with the guards. According to the fax, he had his own cell and could smoke cigarettes.

Prior to his release in 1993, Wei had been taken on a tour of cities near Beijing so that he could “see for himself” the progress China had been making in economic and social development. Wei was a leading dissident figure well known in the West due to his authoring the seminal wall poster “The Fifth Modernization” which he posted on Democracy Wall in Beijing.

After another arrest in 1994 and imprisonment, Wei was released in 1997. He now lives in exile in the United States where he has testified before Congress and met with members of the House of Representatives and the Senate to lobby for legislation meant to advance human rights and rule of law in China.

Obscure Prisoners: Zhang Chengjian (张成俭)

In late November 1994, I flew to Beijing, hoping to have a meeting with the MOJ. They were not available to see me. I secured a meeting with Bai Li on December 2, 1994, where I advised him that I had hoped to hand over a list of little-known prisoners list directly to the justice ministry. He told me to give it to him. He would fax me the response to my Hong Kong office.

A few weeks later, as 1994 drew to a close, I received a fax from Bai Li with information on 13 names on the list.

One of the names that information was provided for was a prisoner by the name of Zhang Chengjian. I had found his name in a book on counterrevolutionaries that I had purchased in a Beijing bookstore. Unhappy with reforms introduced by Deng Xiaoping, Zhang had gathered a group of like-minded people to overthrow the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party, constituting crimes of inciting counterrevolution and establishing a counterrevolutionary group. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison by a Shandong court in 1983, which was extended by seven years for a murder charge in 1998. After several sentence reductions, he was released from prison in 2005.

Ethnic Prisoners

Early in my work with Bai Li, I inquired into the status of prisoners held in Xinjiang and Tibet, including the Kazakh poet Kajikhumar (Qazhyghumar) Shabdan, held in Urumqi Prison Number One, Tibetan activist Jampel Changchub (江白强久) and Tibetan teacher Jigme Sangpo (晋美桑布), both held in Drapchi Prison.

Compared to Han prisoners, getting information on ethnic prisoners proved difficult, as was securing clemency. Jampel Changchub’s sentence was reduced by three years at the end of 1994. Elderly prisoners Kajikhumar Shabdan and Jigme Sangpo both served many years in prison but were released before their long sentences ended. The two Tibetans have passed away, Jigme Sangpo in Switzerland in 2020 where he had been granted political asylum and Jampel Changchub in Tibet.

The List of 100

In February 1995, I traveled to Beijing where I met with Bai Li and a representative of the MOJ. Prior to the meeting I had gathered all the information that Bai Li had given me in 1993 and 1994 into a booklet that I faxed to Bai Li. At our meeting in February, I asked for my interlocutor’s reaction to the booklet. “You have accurately reported what we told you,” Bai Li’s responded. I then asked, “Shall we continue?” Bai Li nodded yes.

I apologized for giving them so much work and suggested presenting four lists of 25 names, one each quarter. They agreed. We shook on this “deal,” and I handed over the first list of 25 names.

I returned to Beijing in April and met with Bai Li and a representative of the MOJ. It was a frosty meeting. I was nevertheless given a response to my February list. Information was provided on 18 prisoners including Zhao Fengping (赵凤平), a political dissident in Jilin Province and Yang Lianzi (杨连子), a June 4 poet and troubadour from Gansu Province.

Zhao Fengping was the leader of a group of counterrevolutionaries based in Jilin Province. I tracked him down by searching through state newspapers at the Universities Service Center in Hong Kong. Zhao had put up Wei Jingsheng’s “Fifth Modernization” on a wall in Shenyang. He was sentenced to life in prison, subsequently reduced to 13 years.

Yang Lianzi roamed Tiananmen Square singing ballads to the protesters. He became friends with Hong Kong-based human rights activist Robin Munro, who asked me to put Yang on one of my lists. Yang had been given a 15-year sentence for counterrevolutionary propaganda soon after the quelling of the protests.

Both Zhao Fengping and Yang Lianzi were released before their sentences expired.

The Bai Li Channel Closes

In late May 1994, President Bill Clinton renewed China’s (MFN) without linking the trade status to human rights. One of the conditions that Mr. Clinton and Congress had imposed on renewing MFN was the accounting of prisoners detained after the June 1989 protests.

The Chinese government no longer had an incentive to provide information on prisoners, but they continued to give me information through the Bai Li channel and other channels. One of the reasons was that former US Ambassador to China Winston Lord had pointed out that the Chinese government had said that, if the pressure of MFN revocation were taken off the table, China would take steps on human rights. Ambassador Lord challenged the Chinese government to make good on that promise.

At the Spring 1995 session of the Geneva-based Human Rights Commission (renamed the Human Rights Council in 2005), the United States and the European Union lobbied for the adoption of a resolution condemning China’s human rights record. I received a fax from China’s MOJ advising me that it would stop providing me with information on prisoners. (The resolution failed by one vote.)

In May 1995, the State Department issued a visa to Taiwan president Lee Teng-hui (李登辉) so that he could give a speech at his alma mater, Cornell University in which he criticized China. Beijing was furious. Among several other dialogues, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that the human rights dialogue with the United States would be suspended. The People’s Liberation Army began firing missiles over Taiwan, and the United States responded by deploying two aircraft carrier groups to waters around the island. Tensions between the two countries were high. The Bai Li channel closed, never to reopen. After my 1995 meetings, I never saw Bai Li again. I continued to submit lists and receive information from other entities, however, and continue to do so to the present day.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.