In the aftermath of 9/11, Chinese President Jiang Zemin resolved to use the attacks to fundamentally improve relations with the United States. In doing so he ignored Vladimir Putin’s entreaties and the advice of several close aides to distance China from the United States. The principal goal of Jiang’s strategic move was to drive a wedge between Taiwan, then headed by Chen Shuibian, and the United States, led by George W. Bush. Shortly after taking office President Bush had pledged to do whatever it would take—perhaps including the use of nuclear weapons—to help Taiwan defend itself.

Jiang sought the advice of his soon-to-be-appointed foreign minister Li Zhaoxing who had recently returned to Beijing from Washington D.C. where he served as China’s ambassador to the United States. Li was impressed by how deeply members of Congress cared about the welfare of China’s political prisoners. Concern for one prisoner in particular, Ngawang Choephel, an ethnomusicologist who had studied at Vermont’s Middlebury College, made a big impact on the ambassador. Citing China’s treatment of Ngawang, then serving an 18-year sentence for espionage, Senator Jim Jeffords, a pro-trade Republican representing Vermont, had voted against renewing China’s Most Favored Nation (MFN) trading status.

As part of the effort to improve relations with the United States, Jiang Zemin decided to start releasing high-profile political prisoners.

Who to Release?

By the end of 2001, I had been intervening on behalf of political prisoners for more than 10 years and had helped around 250 prisoners gain early release (according to a rough count by The Sunday New York Times Magazine for a 2002 profile on me). My greatest assets in these efforts were skills and relationships developed over a 25-year business career in China. Once the decision was made to release political prisoners, China’s leadership turned to me for advice and assistance regarding who should be released.

We agreed that the first to be released should be Ngawang Choephel. On January 20, 2002, he was released on medical parole from De Yang Prison in Sichuan Province and flown to the United States.

As anticipated, the reaction in Washington was positive.

In March, 2002 I flew to Beijing for discussions on prisoner releases. My interlocutor was a member of a five-man group of senior officials headed by Jiang Zemin that was responsible for determining which prisoners would be released, when, and by what means. It was decided that medical parole was the best option since prison authorities could grant it without having to go through a court. I suggested releasing the elderly Tibetan schoolteacher Takna Jigme Sangpo who was believed to be the longest serving prisoner convicted of counterrevolution. (His sentence had been extended twice for staging protests in Drapchi Prison.)

For Tibetans living overseas, gaining Jigme Sangpo’s release was a high priority. Every China-related human rights group, including those that focused on Tibet, had lobbied hard for his release; my foundation and I had included his name on numerous prisoner lists submitted to Beijing and, in August 2001, just weeks before the 9/11 attacks, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, had urged a group of leading business leaders, celebrities, and athletes, who had convened in Los Angeles, to press for Jigme Sangpo’s release.

Negotiations

Shortly after I arrived in Beijing on March 10, 2002, detailed negotiations began. At my first meeting with my interlocutor, I was told that Jigme Sangpo did not want to leave prison where he was highly respected and looked after by his fellow prisoners. (I’d heard the same thing from Congressman Tom Lantos who had received a letter from the Chinese embassy in Washington DC to that effect.) When I said that I found it hard to believe that the elderly Tibetan preferred to remain incarcerated, my host offered to make arrangements for me to go to Drapchi Prison, on the outskirts of Lhasa, so that I could ask him myself.

Naturally, I was eager to meet Jigme Sangpo, but not in prison. In the past, he had staged protests when foreigners—notably the Swiss ambassador—visited Drapchi. In each case, the resulting punishment was harsh and added many years to his prison term. Despite assurances that, whatever happened, the Tibetan prisoner would not be mistreated, I held firm. I suggested that Jigme Sangpo be granted medical parole and placed in a monastery, a hospital, or in the house of a relative.

Discussions were put on hold and resumed two days later. No monastery or hospital would shelter the elderly teacher, fearing the consequences of a huge security presence. Likewise, no relatives dared take him in. Having heard that Jigme Sangpo had a niece living in Lhasa who was a Communist Party cadre, I suggested that she be ordered to temporarily house her uncle; surely, as a loyal party member, she’d be willing to do so.

That did the trick. Details of Jigme Sangpo’s release and my visit to Lhasa were hammered out. I asked for permission to bring my own translator (I speak passable Chinese, no Tibetan.), which was denied—the explanation being that, as a teacher, Jigme Sangpo would know at least some Mandarin. I also asked to visit the U.S. consulate in Chengdu before or after my visit to Lhasa. (In those days, all flights to Lhasa from Beijing passed through the Sichuan capital.) This was also denied. However, the Chinese government placed no restrictions on Jigme Sangpo’s eventual choice of foreign residence. (Switzerland, with its large Tibetan population, had expressed an interest in hosting the Tibetan prisoner.) Its only condition was that he fly to the United States first.

Before the meeting broke up, we agreed that I would return to Beijing in two months, then fly to Lhasa with an official from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to meet Jigme Sangpo.

Two weeks later, on April 1 at 1 AM, as I drove from Orlando to Port Saint Lucie, Florida to visit my ailing mother, I received the news on my cellphone that Takna Jigme Sangpo had been released from prison on medical parole on March 31, 2002. His niece had taken him in.

Getting to Lhasa

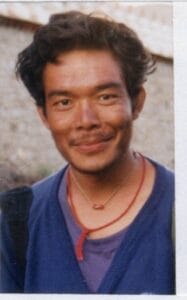

Before returning to China in June, I prepared for my trip to Lhasa by buying a disposable camera and a bottle of Jack Daniel’s (for medicinal purposes!). I also needed a picture of Jigme Sangpo, whom I’d never laid eyes on. Without it, how could I be sure I was meeting the right man? By then I was working with Tibetans living abroad, one of whom sent me a photograph taken in Jigme Sangpo’s cell at Drapchi Prison. It pictured the elderly prisoner sporting a long white beard, huddled in a corner. Because of his deteriorating eyesight, he wore his glasses at a tilt.

I also wanted to confirm with a relative of Jigme Sangpo living in Washington that the Tibetan could indeed communicate in Chinese. And, I needed confirmation of the Swiss government’s willingness to care for him. Unlike the American government, which typically does not give financial support to political prisoners admitted into the country, Switzerland provides a generous monthly stipend. The country is home to a large Tibetan community, and houses a place of worship and study in the small village of Rikon on the outskirts of Zurich.

On June 6, I arrived in Beijing. Over the next nine days I had three meetings with my interlocutor and his deputy and was introduced to my traveling companion, a third secretary in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I met with senior officials of the Ministry of Justice and the Supreme Court, as well as diplomats of the American and Swiss embassies.

On June 16, my companion and I flew to Lhasa via Chengdu. Late that afternoon we arrived at Gonggar Airport and found no one there to greet us. This was my first taste of the hospitality of my Tibetan government hosts, who clearly wanted nothing to do with me. Gonggar Airport is almost 100 kilometers from Lhasa. My companion found a phone and organized a car to come get us. More than two hours later we arrived at the Lhasa Hotel where an official from the Tibet Autonomous Region’s (TAR) Foreign Affairs Bureau met us. He placed khatas around our necks and briefly went over the program. There was no invitation to dinner.

The next day a car came to fetch us and take us to the office of the Foreign Affairs Bureau for a 9:30 AM meeting. In attendance were officials from the TAR Political and Legal Committee of the Communist Party, the TAR Prison Administration Bureau, the Foreign Affairs Bureau, and the Lhasa Public Security Bureau (PSB) which was responsible for monitoring Jigme Sangpo’s medical parole.

I began by asking if the hosting officials would like to say a few words of welcome, but they all declined. For my opening question, I asked if a foreigner had ever been allowed to interview a prisoner on medical parole, to which the PSB official answered no. When I asked if they knew whether or not Jigme Sangpo would like to go abroad for medical treatment, they said I could ask him myself.

I was then advised that medical parole is granted for an initial period of six months, after which the parolee’s condition is reviewed. If the parolee is deemed not seriously ill, he or she is returned to prison to serve the remainder of his or her term. It was clear to me that this is what TAR officials intended to do.

After the meeting I was taken on a tour of the city’s notable sites. When I thanked the official accompanying me, I was told very pointedly that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had paid for the tour, not the TAR government; thanks weren’t necessary.

The Meeting

On the afternoon of June 17, 2002, my companion and I were driven to the home of Jigme Sangpo’s niece. As we approached, I noticed an iron chain across the road leading into the residential compound and security was everywhere, with armed police on the rooftops and a PSB guard post near the front door. As we entered, the niece stuck out her tongue in the traditional Tibetan greeting. We went into a room that was filled with officials and uniformed and plain clothes police, and I was told to take a seat on a couch against the wall, directly in front of the audience.

Then Jigme Sangpo was led into the room. Wearing his glasses at a tilt, he matched his photo. This was the frail old man for whom so much security had been laid on. He sat down next to me on the couch.

I immediately asked him if he spoke Chinese, to which he shook his head no. I didn’t know how to proceed. How could I be sure that my questions and Jigme Sangpo’s answers were rendered accurately? Then a young woman in the room stepped forward and volunteered to translate. The atmosphere was tense and there was an air of displeasure within the group.

With no time for pleasantries, I asked Jigme Sangpo about his health and whether he wished to seek treatment abroad. Though he suffered from multiple ailments and hoped to go to the U.S. for treatment, he’d been told that approval would only be granted if he promised never to return to Tibet. “This,” he said, “I am not willing to do.”

At this point the interview came to an abrupt halt. Guards came in and, as they took Jigme Sangpo away, he broke loose and put his head on my chest. There were tears in his eyes. Addressing the room, I said that I had been told Jigme Sangpo did not want to leave prison; now that I knew the truth, I planned to return to Beijing and work with the central government to arrange Jigme Sangpo’s travel to the United States for medical treatment.

With that, I got up to leave. Waiting outside was the director of the public security bureau who asked me what Jigme Sangpo had said. When I told her that he wanted to go to the U.S., and that I was going to make it happen, she blurted “You can’t do that! He’s old. He needs to be taken care of.” I told her that she and her colleagues had been taking care of him for long enough, and that now it was someone else’s turn.

Leaving Lhasa

That night I shared a simple meal with my traveling companion in the hotel coffee shop. After our yak burgers arrived, she told me that her colleagues at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs were jealous that she had gotten to accompany me on this historic trip. She continued: “We debate among ourselves why you chose to give up your business career to do this kind of work, to travel so far to help an old Tibetan you’ve never even met.” I asked her what she thought, and I appreciated her answer: “We think that you believe there are more important things in life than making money.”

On July 13, 2002, one month after my meeting with Jigme Sangpo in Lhasa, the elderly Tibetan boarded United Flight 850 in Beijing, bound for Chicago. Accompanied by an officer of the American Embassy, he arrived in Chicago that afternoon (local time) and immediately flew to Washington, where he took up residence in the home of a relative. Tibetans around the world celebrated.

Aftermath

Jigme Sangpo eventually settled in Rikon, Switzerland, where I have visited him on several occasions and where my youngest son Rene spent several weeks with him in the summer of 2010. He has thanked me on behalf of Tibetan and Han prisoners. This kind and gentle man bears no ill will against Han Chinese.

Ever since Jigme Sangpo’s release, Tibetans around the world have gone out of their way to express their gratitude. On one occasion, I was hosted to a fine meal and plenty of drink in London by a former prisoner who was in Drapchi Prison when Jigme Sangpo was there. He told me this story:

“On socialist education days in the prison, we were gathered together to hear speeches by the wardens. Seated on a stool was Jigme Sangpo. The warden would tell us: ‘If you want to get out of here, you will admit guilt, accept reform, obey all instructions, and perform manual labor. If you do so to our satisfaction you will be released. On the other hand, if you’re like this old fox (Jigme Sangpo) and don’t accept reform and admit guilt, you will never get out of here. The only way Jigme Sangpo will leave Drapchi is in a box.”

My drinking companion finished up by saying that, “with Jigme Sangpo’s release, every prisoner in Drapchi experienced a great sense of joy, of hope, knowing that if the Chinese government could free him, they could free anybody.” In the following months, the Chinese government granted early release to a number of Tibetan political prisoners, including Ngawang Sangdrol and Phuntsog Nyidron, leaders of the Singing Nuns of Drapchi.