<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

Download & read this story as a PDF.

Three months after the 9/11 terror attacks, I resumed my travels. My first trip was to Washington DC, where I accepted the Eleanor Roosevelt Human Rights Award at the State Department on December 13, 2001. I was joined at the ceremony by two other awardees – Congressman Frank Wolf, a lion of human rights advocacy, and Barbara Elliott, a fierce advocate for refugees fleeing communism – and members of my family.

For the next two-and-a-half years. I kept to a grueling schedule of domestic and international travel. I made frequent trips to Washington DC, where I met with members of Congress and the Bush Administration, including Lorne Craner, Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights, for whom Dui Hua crafted numerous prisoner lists for use at the annual human rights dialogues between the United States and China. (The dialogue has been suspended since 2016.) A highlight was my testimony to the Congressional Executive Commission on China (CECC), a body I lobbied to establish in the aftermath of President Clinton’s decision to extend China’s Most Favored Nation status without conditions. My testimony – An Arsenal of Human Rights – was delivered on April 11, 2002.

I traveled to other cities in the United States as well, visiting with NGO representatives and supporters, as well as speaking at universities around the country. I also traveled to Australia where I met with government officials and spoke at gatherings at universities and elsewhere.

On my many trips to China during this period I focused on helping secure the release of long-serving counterrevolutionaries, including the ethno-musicologist Ngawang Choephel. I logged two trips to Lhasa where I helped gain freedom for the elderly teacher Jigme Sangpo and the young nun Ngawang Sangdrol. In Beijing I worked with officials of the Ministry of Justice and Ministry of Foreign Affairs to secure the early release of Democracy Party activists Xu Wenli and Wang Youcai. Of special importance was the early release of American citizen Fong Fuming, a businessman, convicted of state secrets violations. This was the first case of an American citizen imprisoned in China that I worked on. It would not be the last.

On my trips to Europe, I focused on securing support from European governments, including those of Switzerland and Scandinavian countries. These efforts were successful and helped ensure the financial viability of Dui Hua for years to come.

June 2004: Washington and New York

On June 5, 2004, I flew to Washington DC for five days of meetings and events. I briefed staff of the CECC on Dui Hua’s work, and addressed a gathering organized by a grantor where I updated the group on developments in Hong Kong, notably the debate over Article 23 in which I had played a role.

Meetings were held with State Department officials in charge of China and human rights, members of Congress, including Senator Chuck Hagel (R-Nebraska), Congressman Doug Bereuter (R-Nebraska), and Congressman Frank Wolf (R-Virginia), as well as senior staff of committees dealing with China. I met with Minister Lan of the Chinese Embassy and staff of human rights groups including Amnesty International.

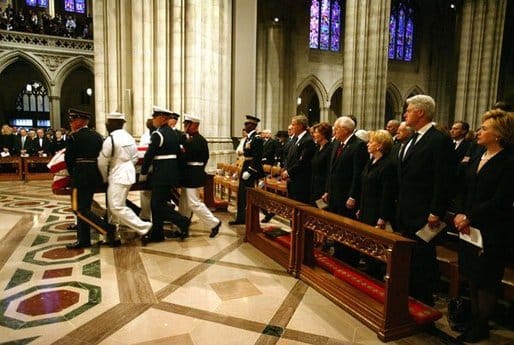

The day I arrived in Washington, former president Ronald Reagan passed away. I followed news of his death closely, watching unfolding events on my hotel room television. I have painful memories of doing so, not least because I was suffering from a bout of kidney stones, two of which I passed with considerable discomfort.

On June 10, I took a morning train to New York. The same day I met with Wang Guangya, China’s ambassador to the United Nations. We met at the Chinese Mission. Before meeting me, Ambassador Wang had signed the book of condolences for President Reagan at the US Mission.

Our meeting was an exceptionally friendly one. I mentioned that I was interested in applying for Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Committee (ECOSOC) of the United Nations, the body that oversaw the Human Rights Commission, now the Human Rights Council, in Geneva. Ambassador Wang replied: “I will support you, and if any of my colleagues give you a hard time, let me know.” In the meeting were other diplomats assigned to the mission, including Li Xiaomei, then China’s representative on the NGO Committee, now Special Representative for Human Rights of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing.

I left the mission and headed to my sister-in-law’s brownstone in the city for dinner. Pat worked at the United Nations, and she offered to introduce me to the person in charge of NGO accreditation the next day, June 11, 2004. The person in charge was a French woman, a longtime UN employee.

The lady was getting ready for her long summer vacation in France and had little time for me. She asked what I wanted, and I told her that I’d like to apply for ECOSOC consultative status. She handed me the application form and asked, “Which country do you work on?” “China,” I replied. “Forget it,” she remarked, with a wave of the hand. China and its allies had blocked applications of virtually all human rights groups, like Human Rights in China, that worked exclusively on China.

I straightened her out. “I met with Chinese Ambassador Wang Guangya yesterday, and he told me that he would personally support Dui Hua’s application.” You could have knocked her over with a feather.

At the next meeting of the NGO committee, applications by NGOs for consultative status were considered. One by one, the committee chairperson read out the names of the applicants. It was a lengthy list. Typically, if a country objects to an NGO’s application, the committee registers its objection, and the chairperson moves on. “The Dui Hua Foundation,” the chairperson intoned. Waiting to object were Chinese allies Pakistan and Cuba who looked for a signal from the Chinese representative. Li Xiaomei sat motionless as other representatives shifted in their seats.

After the chairperson finished ticking off the names of NGO applicants, he or she returned to Dui Hua. “I ask again. Are there any objections to The Dui Hua Foundation’s application for Special Consultative Status.” Li Xiaomei told me later: “I was very embarrassed, but I registered no objection.” Dui Hua was granted the much-coveted status, becoming the only independent human rights group focused on China to be given this status. That remains the case to this day.

Making Use of our UN Status

Early in 2005, a fellow Dui Hua director, Bill Simon, traveled to Geneva with me to obtain our badges that granted us privileges at the Palais des Nations, home of the Human Rights Commission. Since 2005, I traveled to Geneva at least once a year before the Covid-19 pandemic made international travel impossible.

In Geneva I stayed at the Hotel Ambassador through the generous support of the hotel’s owner, Madame Rossotto. I fell in love with the city, and took long walks along the lake to Palais Wilson, site of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and many of the special procedures of the Human Rights Council. I particularly enjoyed spending time in the Old City, dining at its restaurants with an old friend, Christophe Swinarski, a distinguished human rights scholar who had served for many years with the International Committee of the Red Cross, also headquartered in Geneva.

Dui Hua has made good use of its special consultative status. The foundation has made submissions to all of China’s and the United States’ Universal Periodic Reviews (UPR), a process whereby every member of the United Nations’ human rights record is scrutinized every 4-5 years. Our submission to China’s third UPR in 2018 was of special importance. We focused on judicial transparency, examining the decision to post judgments on the Supreme People’s Court’s China Judgments Online (CJO), which we hailed (attached to our statement were prisoner lists of names found on CJO). Unfortunately, in 2021 the court purged the website of judgments involving cases of endangering state security and other sensitive crimes, dealing a blow to Dui Hua’s work compiling prisoner lists for submission to the Chinese government. For both the Chinese and US UPRs we examined capital punishment; when it comes to the death penalty, both countries are outliers.

In addition to its work on UPRs, Dui Hua has worked on issues related to women prisoners and arbitrary detention. We lobbied for China to invite a delegation from the newly established Working Group on Discrimination Against Women in Law and Practice. The group visited China in December 2013, not long after China’s UPR.

Dui Hua has worked closely with the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention to secure favorable opinions on the cases of American citizens judged to have been arbitrarily detained by Chinese authorities: US businesswoman Sandy Phan-Gillis and US businessmen Mark Swidan and Li Kai, both of whom remain imprisoned as of this writing.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.