<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

Beginning in 1990, I testified on a dozen occasions to Congressional committees in Washington DC. My last testimony was delivered in 2011. On different occasions, I appeared before the House Ways and Means Committee, the House Foreign Affairs Committee, the Senate Finance Committee, and the Congressional Executive Commission on China (CECC), a body whose establishment I had called for in the wake of President Bill Clinton’s decision to unconditionally renew China’s Most Favored Nation trade status in May 1994.

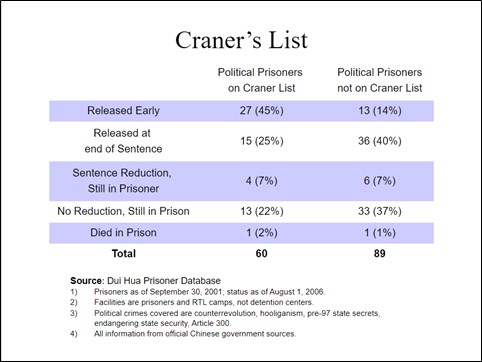

Of special importance was my testimony delivered to the CECC on September 20, 2006. In this testimony I described what had happened to 75 political prisoners whose names were on a list of prisoners handed to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs by Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Rights, and Labor Lorne Craner in the summer of 2001. I concluded that “If you were on the list, you had a better than 50 percent chance of being released or given a sentence reduction in the ensuing five years. That’s three times better than the rate of early release for political prisoners that we know of who were serving sentences in September 2001 but who weren’t on Craner’s list.”

I based my conclusion that being on a prisoner list significantly increased the chance of early release both on my analysis of the Craner list and on interactions with the Chinese government in the 15 years prior to my testimony, including communications with the State Council Information Office (SCIO) from 1991 to 1994. During this period, I asked about and was provided information on more than 70 prisoners, including Democracy Wall prisoner Xu Wenli (徐文立); the information I was given specified the hour and the day he would be released. I was given information on several elderly Catholic priests, as well as many other political prisoners.

Of special significance was a fax received from the SCIO in December 1994. For the first time, I was given written responses to a prisoner list I had submitted earlier that year to the Ministry of Justice. A number of the prisoners on the list received early releases from prison after I had given it to the Ministry of Justice, including:

- Ge Hu (葛湖): A teacher in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, was 35 years old at the time of his arrest in 1989. He was sentenced to seven years in prison in November 1989 for committing counterrevolutionary offences during the 1989 pro-democracy protests. He developed multiple health issues, but the prison refused to grant him medical parole. Seven days after I requested information on him from the MOJ, he was granted medical release. He returned home to be with his wife and young child.

- Hao Fuyuan (郝付元): A farmer from Shandong Province, a hotbed of counterrevolution, Hao was active in the 1989 protests. He circulated a tape condemning Deng Xiaoping and pushed students to boycott classes and listen to Voice of America. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison. I asked the MOJ about Hao, after which he was granted early release, probably in 1996.

- Zhang Chengjian (张成俭): Another farmer from Shandong Province, Zhang claimed to be Mao Zedong’s son. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 1984 for committing counterrevolutionary offenses. The sentence was extended by seven years in 1988 for killing a fellow inmate. I had put his name on the same list as Ge Hu, handed to the Ministry of Justice on October 31, 1994. In 1995, his sentence was reduced, followed by two more sentence reductions in 1998 and 2001, respectively. Dui Hua learned of his release in December 2001.

Although early releases of political and religious prisoners on Dui Hua lists have become fewer in recent years, especially after the Covid pandemic when prisons adopted the unofficial “entry only, no exit” policy, notable acts of clemency still in take place. Among the most noteworthy is the early release of Liang Jiantian (梁鉴添), a printer of Falun Gong literature, announced by Dui Hua in March 2022.

I began asking about him shortly after he was sentenced to life in prison in 2000, not long after Falun Gong was banned. I put his name on 20 lists submitted to the Guangdong Government. In 2007 his life sentence was commuted to 20 years in prison. Multiple sentence reductions were granted until the final six-month reduction in October 2021.

Despite strong evidence to the contrary, policy makers in Washington generally dismiss the importance of submitting prisoner lists to the Chinese government. A principal venue for submitting lists and discussing cases used to be the bilateral human rights dialogue. This was suspended by the Obama administration in late 2016 and has not been resumed, even though Beijing has signaled a willingness to hold another session.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.