<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

In October 1992, I was in Hong Kong preparing for a trip to China the next month. It would be my tenth human rights trip to Beijing since January 1991. Many of the names of prisoners I raised on those trips had been granted early release, a reflection of Beijing’s concerns over the possibility of losing its bid for the 2000 Olympic Games and the prospect of Bill Clinton defeating George H. W. Bush in the November 3, 1992 presidential election. Clinton had campaigned on stripping China of its Most Favored Nation (MFN) trading status if elected.

Preparations for trips to Beijing typically took several weeks. Appointments with officials in the Chinese government needed to be requested and, if granted, followed up with details including, on my part, the submission of political and religious prisoner lists. More mundanely, I needed to contact my regular driver and book a room at my usual hotel. Appointments with foreign diplomats and Beijing-based journalists also had to be fixed.

For the November 1992 prisoner list, I wanted to include imprisoned Roman Catholic clergy and senior laity, of whom there were more than 100 at that time. In January 1992, I submitted lists to the central government, including to the Religious Affairs Bureau of the State Council, with names of imprisoned Catholic prelates. In May 1992, I was informed of the early release from prison of three high priority underground leaders I had advocated for. This experience was on my mind as I put together my list for the mid-November 1992 trip to Beijing.

Father Giancarlo Politi, a Good Priest

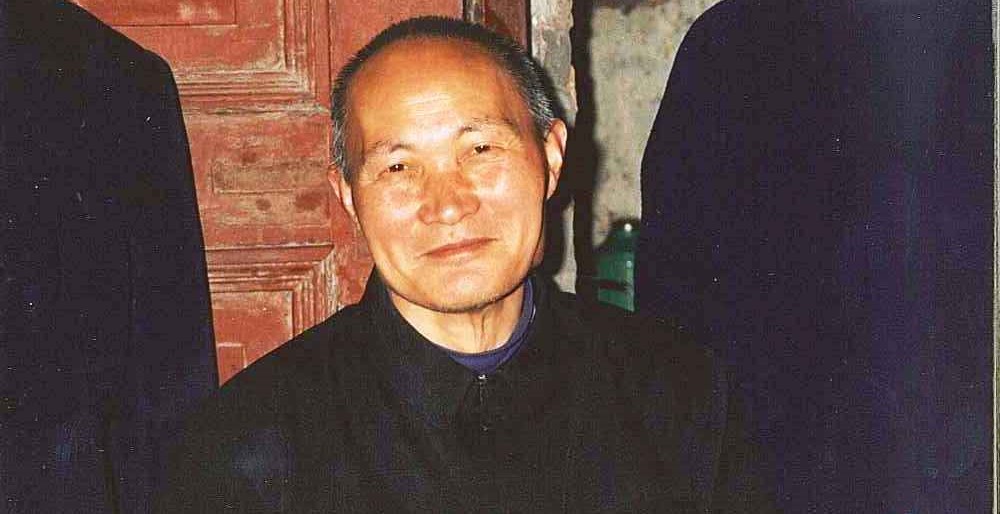

For that first list of Catholic prisoners submitted in January 1992, I had relied for information from Father Giancarlo Politi, a Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions (PIME) missionary assigned to Hong Kong. Father Politi produced and edited authoritative materials on the Catholic Church in China, gained from first-hand readings, observation, and experience in the field. The priest arrived in Hong Kong in 1970 and began traveling widely in China to make contact with Catholic communities in 1986. He was deeply concerned about the fate of imprisoned Catholic clergy. Politi usually travelled alone on his trips to the mainland, though he was occasionally accompanied by Hong Kong Catholics. These were dangerous trips, fraught with peril.

I reached out to Father Politi for assistance. I gave him a call at his place of work and residence, the PIME House in Sai Kung, Hong Kong. We agreed to meet for a “simple lunch” the next day. I contacted my driver – I was still a consultant to Occidental Chemical drawing salary and benefits, including use of a Mercedes 280SE. I arranged to be picked up at my apartment on Coombe Road the following morning.

Upon arrival at PIME House on November 5, 1992, I was met by Father Politi. He would later recall me as “a big man in a business suit with a driver and a Mercedes.” He ushered me into his office, where desks and shelves were piled high with publications and notes from his trips to China. I thanked Politi for sending me copies of PIME’s AsiaNews – he was editor at the time – and his latest mimeographed list of imprisoned Catholic bishops, priests, and senior laity. These lists informed virtually all of the publications of Western human rights groups that dealt with jailed Catholics.

I asked Father Politi for a complete set of the lists, going back several years. He demurred, saying that the most recent list had incorporated the names of all imprisoned clergy on previous lists.

Politi’s Samizdat

I insisted: “As a businessman, I always try to collect as much information as possible on a transaction,” I said. “It sometimes happens that critically important information is inadvertently omitted from the record.” Politi relented. He called his assistant, a young seminarian, and asked him to put together a complete set of the mimeographed lists, which I likened to samizdat of the old Soviet Union, unofficial publications of dissidents and activists that were widely circulated among networks in the country and abroad.

Politi escorted me to the dining hall, where we were joined by a dozen PIME monsignors and priests. The “simple lunch” turned out to be a feast with plates full of pasta, vegetables, meat and fish, washed down with glasses of chianti. After finishing up, I headed for my car. I was met at the door by the seminarian. He gave me a stack of Politi’s lists.

I was driven back to Hopewell Centre in Wanchai, site of my office. I spread out the copies of Politi’s lists on my conference table and began going through them. I quickly discovered that a name – that of Father Li Fangchun 李芳春 – had been dropped from the most recent list. I called Politi and he confirmed that a terrible mistake had been made. I then prepared an urgent appeal and faxed it, on November 7, 1992, to Vice Minister of Justice Jin Jian with whom I had established a good relationship.

Father Giuseppe Li Fangchun, born in Shangqiu County, Henan Province, in 1935, underwent formation at the Kaifeng Seminary, a regional seminary that served the Kaifeng Archdiocese and other dioceses in Henan Province and Shanxi Province. The seminary was considered one of China’s best, on a par with Shanghai’s Shesan Seminary. It was for many years under the administration of PIME. Kaifeng itself was one of the most Christian cities in the country, sometimes called the Galilee of China. It was also home to China’s largest Jewish community.

Li was ordained in secret in 1957. (Around one dozen Kaifeng seminarians were secretly ordained during the 1953-1957 period.) The last PIME missionary in Kaifeng was expelled from China in 1954. The seminary was closed in 1958 due to “lack of enrollment.”

According to the Chronicles of the Kaifeng Seminary published by the official Henan Catholic Administrative Commission, Li Fangchun was detained for counterrevolutionary activities together with other clergy, including the dean of the seminary, Ma Changren, around the time the seminary closed in 1958. The detentions took place during the Sufan (肃反) Movement to purge counterrevolutionaries. (Ma died in prison in 1962.) Li and the others had allegedly formed a “counterrevolutionary group” that secretly held masses, opposed the consecration of the officially appointed bishop of the Kaifeng Archdiocese, and criticized the official Catholic Patriotic Association. The Sufan Movement took place from July 1955 until early 1958. An estimated 214,000 people were detained; approximately 53,000 died, many by execution.

After his detention in 1958 Father Li was tried and sentenced to 14 years in prison for counterrevolution. He served his sentence at Kaifeng Prison, currently known as Henan Number One Prison, a maximum-security prison that has housed many political prisoners and those awaiting execution over many decades.

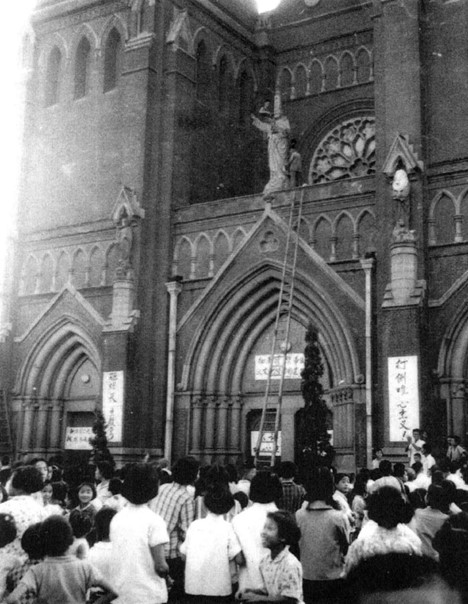

He was due to be released from prison in 1972. In that year, the Cultural Revolution, which began in April 1966, was still underway, although its worst excesses had for the most part passed. The Cultural Revolution was a period when the Catholic Church, or what was left of it, was under fierce attack. Churches were ransacked, priests “struggled” and beaten, and worse. I vividly recall being told by the Polish Consul General in Guangzhou – where there was a joint venture shipping company between China and Poland – that the priests at the Catholic church on Shamian Island had been frog marched by Red Guards from the church and lynched from lamp posts on Renmin Road in those horrifying days.

It is not known whether Li Fangchun was released on schedule in 1972 or had his sentence extended. He might have been placed in a re-education through labor camp, maybe in a remote area. He eventually returned to Shangqiu, a city of some 20,000 Catholics, probably in the late 1970s at the start of the Opening and Reform period when repression against Catholics eased. He began his ministry at the reopened Shangqiu South Church.

Father Li’s freedom proved to be short-lived. He was detained again in February 1983 and sentenced to 12 years in prison for counterrevolutionary activities, including membership in a counterrevolutionary group and counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement. He was sent back to Kaifeng Prison to serve his sentence.

November 1992 Trip to Beijing

I flew to Beijing on a Dragonair flight on November 16, 1992. I was picked up by an officer of my host organization, the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT). After checking into the Great Wall Sheraton and taking the obligatory “rest,” I was whisked away to a welcoming banquet hosted by CCPIT Vice Chairman Xie Peijing at the nearby Kunlun Hotel.

The next five days were filled with meetings. I sat down for discussions with senior officials of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the State Council Information Office, the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations and Trade, and the Chinese People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs. Bill Clinton had just been elected, and his name was on everybody’s lips. They asked if I thought that Mr. Clinton would revoke China’s MFN status.

On Thursday November 19, 1992, I met with Wang Mingdi, director of the Ministry of Justice’s Laogai (Reform through Labor) Bureau (later renamed the Prison Administration Bureau). Wang gave me information on Li Fangchun. Li had been detained on February 23, 1983. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison for counterrevolution, reduced by one year in 1984 and one year in 1988. His sentence was to expire on February 22, 1993. No information was provided on any supplemental sentences including whether a sentence of deprivation of political rights had been imposed.

Wang didn’t mention that Father Li had already been released from prison on medical parole a short time before our meeting, in late October or early November 1992. He likely had not heard of the release, which suggested that the release had been sudden. Wang Mingdi would confirm the release at our next meeting in March 1993. Medical parole is the simplest way to secure an early release as it doesn’t need the approval of a court.

After briefing the American ambassador at his office in Beijing, I flew back to Hong Kong on Saturday, November 21. I got in touch with Father Politi and we agreed to meet at the Holy Spirit Centre in Aberdeen on Tuesday, November 24. There I told him what I had learned about Father Li Fangchun.

Politi activated the old PIME network in Kaifeng. He was told that the prison wardens had opened the prison gate and unceremoniously tossed Li Fangchun out onto the street around the time of my appeal to Minister Jin Jian. Li was found wandering the streets by a Catholic couple surnamed Cai, a priest and his sister, a Catholic nun.

Li was in bad shape. He could not remember his name, nor even remember that he had been a priest. He walked with difficulty. The couple nursed him back to health. He gradually recalled how he had suffered in prison; he had experienced two heart attacks.

Under Cover of Darkness

Politi travelled to Kaifeng in January 1993. He met Father Li at the couple’s house. After a period spent building trust, the Kaifeng priest, Politi, and Li Fangchun decided to leave Kaifeng early the next morning. A driver who could be trusted — probably a local Catholic — was hired, and at 5:00 AM, after a sleepless night, the group — Li, Politi, and Father and Sister Cai — left Kaifeng in the cold and dark. Politi was under surveillance. As he later put it, “In China, you learn to move under cover of darkness.”

The journey to Shangqiu from Kaifeng — 200 kilometers (about half the length of New York State) — took more than two hours on rough roads (this was long before a freeway was opened to link the two cities.) Father Li was mostly silent, tracking progress by ticking off the stones marking kilometers. Politi told him of our effort to secure his release. Li Fangchun wept.

His home village was about 20 kilometers from Shangqiu. As he approached it, he could see the spire of his old church. He called out for the taxi to stop, and he leapt from the car. As Politi put it, “he ran like a child” to the doors of his church. There he fell on his knees and kissed the earth. The church had long been abandoned; no priests were in sight. A villager, a Catholic, emerged from the shadows and led Father Li away, but not before telling Father Politi to leave right away and never come back. “It’s too dangerous for you, and for us.”

Not long after his return to Hong Kong, Father Politi was recalled to Italy. Those in the local Catholic community believed he was called back in part due to his activism on behalf of Catholic bishops and priests in China, including his trips to the mainland to gain information on local Catholic communities and imprisoned Catholics. Beijing was also said to be angered by Father Politi’s role in leaking photographs of the deceased Bishop Fan Xueyan, lying on a slab. The photos suggested that Bishop Fan, his body covered with bruises, had been mistreated.

Politi’s last trip to the mainland was the one he made to Kaifeng in January 1993 to bring Li Fangchun home to Shangqiu. Shortly after his return to Hong Kong and as he was preparing to return to Milan, Father Politi learned that Li Fangchun had died from his third heart attack.

The Italian missionary never returned to Hong Kong, working in Milan on China issues until he passed away at the age of 75 from complications from a long illness in December 2019. Father Politi gave an on-camera interview to my son Rene and his Oberlin College classmate Jake Hochendoner in October 2013. Much of the information on Politi’s trip to save Li Fangchun comes from that interview.

Father Politi is remembered as a good shepherd by Catholics on the mainland and in Hong Kong, where he served as a parish priest in Yuen Long and Tsuen Wan before taking up his position at PIME House in 1986. He fought to save the Roman Catholic Church from extinction in China during the darkest days of the second half of the 20th century. He will long be remembered.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.