<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

As winter turned to spring in 1992, Chinese officials increasingly turned their attention to the possibility that the country’s coveted trade privilege – Most Favored Nation (MFN) status in the United States – might be removed if the White House changed hands in November. Deng Xiaoping’s friend George H. W. Bush, the incumbent, was expected to be a shoo-in on account of the success of the Gulf War. But after Super Tuesday, March 10, 1992, polls suggested that in a three-way race involving President George H. W. Bush, Arkansas Democratic Governor Bill Clinton, and independent Ross Perot, Bush would poll less than 50 percent.

Furthermore, in December 1991, Beijing had applied to hold the 2000 Olympics, and officials knew full well that its human rights record would prove to be an impediment. I decided to exploit their fears and ambitions by planning a week-long trip to Beijing beginning April 5, 1992.

It would prove to be a remarkable trip, marked by meetings with senior officials and opportunities to intervene on behalf of political and religious prisoners, the latter mostly Catholics. I would also be given information on China’s most famous political prisoner, Wei Jingsheng, and Wang Dan, a leader of the June 4 protests. Concerning Wei, this would be the first time that the Chinese government would address his living conditions, health, and state of mind.

I flew up to Beijing from Hong Kong on the afternoon of April 5. I was picked up by my driver and taken to the Great Wall Sheraton Hotel, near the Embassy District. The Great Wall Hotel was managed by a friend who offered me a generous rate and lots of hospitality, including the occasional drink at the hotel’s well-stocked bar.

The next day, April 6, I met with my host, Vice Chairman of the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT), Liu Fugui. This was followed by a meeting with the Deputy Director of the American and Oceanian Department of the Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations and Trade (MOFERT), Shi Jianxin. These meetings focused on the situation in Congress with respect to MFN, which was grim, in my estimation.

In the afternoon I met with the Supreme People’s Court and, later, Luosang Chinai, a Tibetan official who was a senior official in the Religious Affairs Bureau (RAB, now the State Administration of Religious Affairs). He was accompanied by a lady who was in charge of the department overseeing Roman Catholics, known as the Second Department.

At this meeting I pressed for the release of elderly Catholic clerics Bishop Liu Guandong, president of the underground Catholic Bishops Conference, serving a sentence in a reeducation through labor (RTL) camp, Father Jin Dechen, serving a 15-year sentence in prison for counterrevolution, and Monsignor Wang Yijun, one of China’s longest serving religious prisoners, then serving a three-year sentence in an RTL camp. Luosang Chinai seemed sympathetic.

Six weeks after this meeting, all three of the clerics, held in facilities around the country, were released on the same day.

That evening I was hosted to a welcome banquet by the CCPIT’s Liu Fugui. Mao Tai, the fiery, sorghum-based spirit (120 proof) was poured liberally, and not wanting to be a bad guest, I partook liberally. I returned to the Great Wall Sheraton, where I was met by my friend the manager. We repaired to the bar where we had shots of Black Label chased by beer. Bad idea.

Vice Minister “Gold Prison”

The next morning, I woke up with a ferocious headache. I had a bolt of caffeine and soldiered on, as businesspeople do, meeting my driver and being driven to the nearby Kunlun Hotel, said to be owned by China’s Ministry of State Security. Up the escalator, I was ushered into a large room where I was met with Ministry of Justice Vice Minister Jin Jian (synonymous with “gold prison”) and the Director of the Reform through Labor Bureau (now the Prison Administration Bureau) Wang Mingdi. I had met Wang in October 1991, so we were “old friends.” Wang was a tough prison official who sported a cauliflower ear.

I sat down on a plush chair with a doily as a head rest. A translator sat between me and the vice minister. There were two notetakers next to Wang Mingdi.

After an exchange of pleasantries, Vice Minister Jin came straight to the point. “We have decided to give you information on any prisoner you ask us about, to the best of our ability.” I was told that this was the first time they were offering this privilege to a foreigner.

I looked at Wang Mingdi. He was seated by a table on which there was a big stack of files, each apparently containing information on prisoners.

I suggested to the vice minister that we could save a lot of time if Mr. Wang would simply give me the files on the table next to him.

Vice Minister Jin did not like this idea. “You need to ask us about individual prisoners, using the full name. Don’t just ask about Mr. Wang in Beijing or Mr. Li in Shanghai. Do you have any idea how many Mr. Wangs live in Beijing and how many Mr. Li’s live in Shanghai?!

“Please tell me about Wei Jingsheng,” I replied.

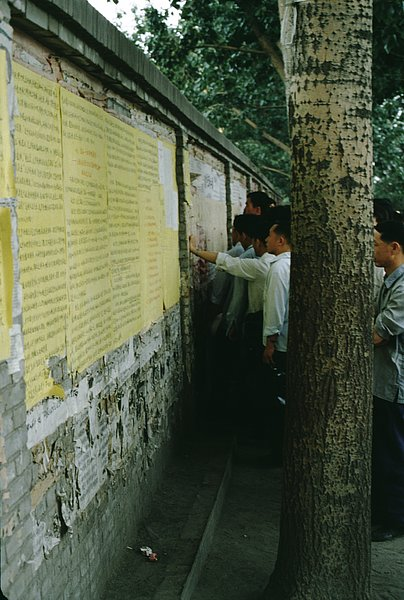

Wei was at the time China’s best-known political prisoner. An electrician and former soldier who had been working at the Beijing Zoo since 1973, Wei was prominent in the 1978 Democracy Wall movement. On December 5, 1978, Wei posted an essay, “The Fifth Modernization,” on Democracy Wall, a stretch of wall surrounding a bus station in Beijing’s western district. Citizens took to the wall and put up “big character” posters in a burst of free speech not seen since the Cultural Revolution – and not seen since. I frequented the wall on many occasions in late 1978; at that time, I was staying at nearby hotels, including the Fuxing, during trips to sell chemicals and technology.

Wei’s poster caused a sensation. It rebutted Deng Xiaoping’s Four Modernizations policy and criticized Deng by name, calling him a dictator. (Deng had called for the modernization of industry, agriculture, national defense, and science and technology.) Wei Jingsheng proposed a “Fifth Modernization”—democracy. Soon Wei was being interviewed by foreign journalists, helped by his able assistant Tong Yi.

Wei was detained in 1979 and subsequently sentenced to 15 years in prison for counterrevolutionary crimes. The Chinese government had said nothing about him for more than a decade.

Wang Mingdi picked a file from the stack and began to read: “Wei Jingsheng, male, Han, born in 1950, middle school education, worker. Sentenced to 15 years imprisonment and three years deprivation of political rights in October 1979. He is currently serving his sentence in a reform through labor camp.”

I asked where Wei was serving his sentence. “What can you tell me about the conditions of his imprisonment? Is he being held in solitary confinement?”

“He’s serving his sentence in a reform through labor camp in Tangshan, Hebei Province. It is not correct to say he’s being held under solitary confinement. His cell has two rooms. He has one room to himself. This room opens onto another room where there are guards. He eats his meals and watches television in this room. He is allowed out for fresh air, and he enjoys gardening. He has been exempted from physical labor.”

“Tell me about his health,” I asked.

Wang replied: “He is in good health, although he smokes a lot. Contrary to reports in Western media, he is not being mistreated. He has not lost his mind. He has not lost his hair nor all his teeth. He likes to stay up late debating with the guards. Wei is a very intelligent, well-informed man, but he is very stubborn. He refuses to admit his guilt or express regret.”

I asked if he could be considered for early release from prison. Wang was blunt. “Unless he changes his attitude, it is unlikely that he will be granted a sentence reduction or parole.”

Once Wang finished talking about Wei, I asked about Wang Dan, a student leader of the Tiananmen Square protests in the spring of 1989. I was told that Wang, like Wei, was proving difficult to reform. He liked reading and stayed mostly in his cell. He too had been exempted from physical labor. He was not being mistreated.

After the meeting with Vice Minister Jin wound up, I was driven to the offices of the State Council Information Office (SCIO) for a meeting and lunch with its director, Zeng Jianhui (who would go on to be chairman of the National People’s Congress Foreign Affairs Committee), and its deputy director Li Yuanchao, China’s future vice president. On the way I reflected on what I had been told, which was in complete variance with the accepted narrative, which was basically that Wei Jingsheng was in bad shape, a basket case.

I told Director Zeng and Deputy Director Li about my meeting with Vice Minister Jin and expressed my concern that people wouldn’t believe the account I had been given about Wei. “Don’t worry,” Zeng Jianhui said. “He’s a vice minister. If he lied to a foreigner, he’d be in big trouble.”

China’s “007”

On the way back to the hotel, I stopped by the Ministry of Public Security, on Tiananmen Square, to see Director General of the International Department Zhu Entao, someone I’d known since 1976 when he was seconded to the Guangzhou Trade Fair’s liaison office handling Americans and Europeans. Zhu, “China’s 007,” feigned ignorance of Wei’s situation, not unexpected as Wei was being held in a Ministry of Justice facility. There was bad blood between the ministries, arising from the decision in 1980 to transfer control of the country’s prisons from the Ministry of Public Security to the newly established Ministry of Justice (MOJ).

I returned to the Great Wall Sheraton and called Nick Kristof of The New York Times. Nick and his wife Sheryl WuDunn had been awarded a Pulitzer Prize for their reporting on the Tiananmen Square protests. He was and remains passionate about human rights.

Nick joined me for drinks at the hotel bar. I read from my notes of the meeting with Vice Minister Jin, leaving nothing out. After an hour, Nick left and returned to his apartment to write up the story. It appeared in The New York Times on April 8, 1992, under the headline “China Offers Peek at Famed Prisoner.”

The day the article appeared I met with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, the prosecutors. That evening I hosted a banquet in honor of my host, the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade’s (CCPIT) Liu Fugui. Gathered around the table were senior officials of the SCIO, the Religious Affairs Bureau (RAB, now the State Administration of Religious Affairs), the Public Security Ministry, the MOJ, and the Procuratorate. I was asked which prisoners’ release would have the biggest impact on American opinion, in Congress and in the general public. I was well prepared, and listed labor leaders, Catholics, and other big names like Wei Jingsheng. After the dinner, the official from the RAB took me aside and told me that the Catholics whose names I had raised would be released.

As anticipated, the reaction to the Kristof article was one of disbelief and, in some quarters, hostility. A Beijing-based journalist of a rival newspaper, a friend who had written a profile about me and my work, called me at my hotel, furious that I had given the “scoop” to Kristof. A New York-based human rights activist wrote a letter to The Los Angeles Times questioning why anyone would believe anything the Chinese government told John Kamm.

Wei Released

I continued to raise Wei on future trips to Beijing, pressing for his release. I met Wang Mingdi on March 9, 1993, at the MOJ’s old headquarters, a shabby, non-descript building on a dusty lane off the road to Beijing airport. Officers played billiards in the middle of the road in front of a bicycle repair shop.

I asked Wang about Wei. “He is such a famous international person; many people are interested in him.” Wang told me that, while Wei was healthy, “He persists in his strong anti-government attitude. He is strongly against socialism and blames the Chinese government for everything wrong in China, even the recent East China floods.”

Wang revealed that at the end of 1992, six months after I raised his name, Wei was driven to Beijing and taken to Science Street in Haidian District. “We let him alight and take a look. He didn’t say much, only ‘I’m from Beijing, but I don’t recognize Beijing.’” Wang Mingdi didn’t rule out an early release, though he said this would be “difficult to consider.” If Wei continued to follow prison rules, his sentence would not be extended. It was not uncommon in those days for counterrevolutionaries to have their sentences extended.

Wei Jingsheng was paroled on September 14, 1993. The reason given was that he had obeyed prison regulations, but many observers noted his release took place one week before the decision by the International Olympics Committee on which city would be awarded the 2000 Summer Olympics. (Beijing lost out to Sydney by a single vote.)

Wei looked well on release. A photograph taken with his brother and sister and published in a western newspaper showed a grinning, somewhat plump Wei. He had lots of hair.

The last time I discussed Wei with Wang Mingdi was in late October 1993, a month after the release. He told me that he had gone to the Tangshan prison holding Wei. It consisted of one big building with 20 individual cells. There was a large garden area, and a field where inmates could play ball. All prisoners had been exempted from physical labor. Wei’s cell was “full of books.” Wang felt that conditions were good enough to allow foreigners to visit, but as far as I know, this never happened. As I was leaving the meeting, Wang expressed regret that Wei had been released. “We did a bad job. We should have kept him in prison.” By then, China had lost its bid to host the 2000 Olympics.

Wei returned to activism after his September 1993 release. He was arrested again in early April 1994 after a meeting with US Assistant Secretary of State John Shattuck in the lobby of the China World hotel, under the eyes of state security agents. He was subsequently sentenced to 14 years in prison for counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement. After international pressure and an appeal to President Jiang Zemin by President Bill Clinton, he was released on medical parole on November 17, 1997 and promptly flown to the United States, where he remains active promoting human rights and democracy in China.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.