<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

I

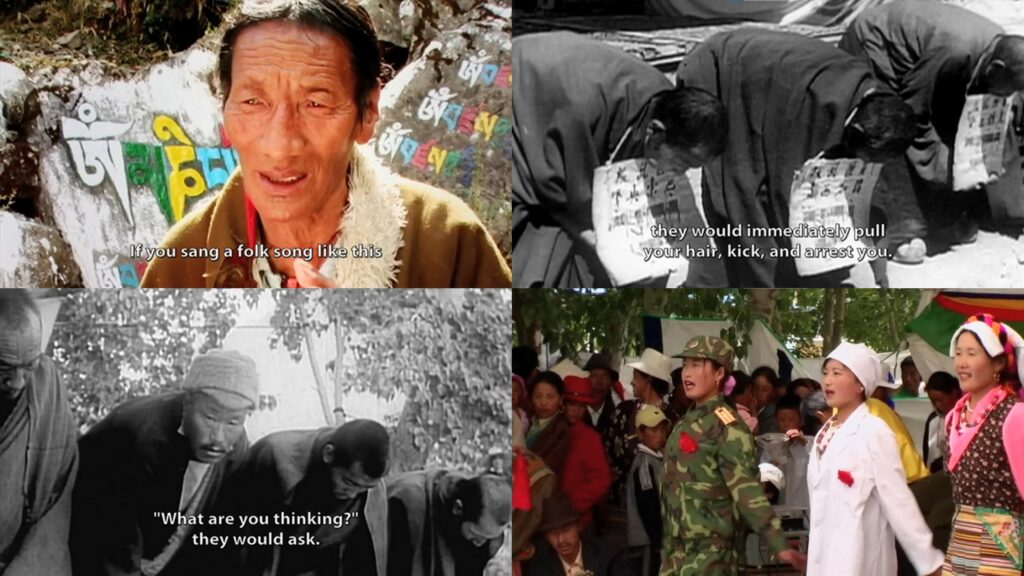

n 1992, Ngawang Choephel, a 26-year-old Tibetan ethnomusicologist born in a small village in Tibet and educated in India, accepted a Fulbright Scholarship to study music and film at Middlebury College in Vermont, thereby establishing a strong personal connection with the people of the Green Mountain State. The connection was to prove crucial in winning his freedom from captivity 10 years later, in 2002.

After getting his diploma, Ngawang traveled to Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), accompanied by an American photographer, in the summer of 1995. They recorded 16 hours of traditional Tibetan song and dance. Not long after the American photographer departed in mid-September 1995, Ngawang was detained by officers from the state security bureau in Xigatse on September 5, 1995. Fortunately, he had given the tapes to a western tourist before he was detained, thereby saving these valuable materials from confiscation and destruction.

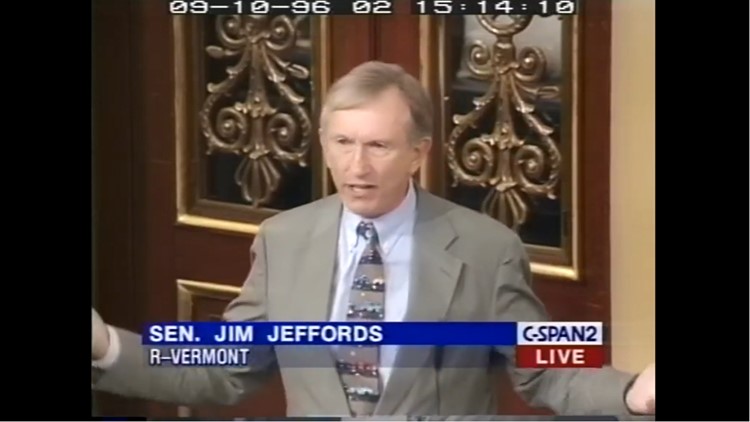

After detention, Mr. Choephel was placed in Nyari Detention Center in Xigatse, Tibet, where he was mistreated. Not long after Ngawang Choephel was formally arrested, Vermont Senator Jim Jeffords wrote, in October 1996, to the Chinese Embassy in Washington seeking information on Ngawang Choephel, beginning a years-long effort to secure his freedom. China’s ambassador to the United States, Li Zhaoqing, responded to Senator Jeffords’ letter with information on Ngawang’s health. Ambassador Li acknowledged that the prisoner had contracted bronchitis, pulmonary infection, and hepatitis around October 1998. (Another source in the Chinese government told me that Ngawang had developed a urinary infection.)

In the letter, Ambassador Li accused Ngawang of spying for the Dalai Lama (the “Dalai Clique” in his words). Two months later, Ngawang Choephel was tried and convicted for espionage and counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement and sentenced to 18 years in prison with four years deprivation of political rights. Ngawang appealed the sentence, but on September 24, 1997, the TAR Higher People’s Court rejected his appeal and upheld the intermediate court’s judgment. He was first admitted to the infamous Drapchi Prison and then transferred to the Powo Tramo Prison, where he was treated somewhat better.

I began my work on Ngawang Choephel’s case in 1997, placing his name on a list of political prisoners handed over to the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) in Beijing. The following year I submitted another list to the ministry. The ministry confirmed details of his conviction and sentencing. I raised his case in meetings with the justice ministry and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) in both 1997 and 1998. At the same time, I researched Chinese law to see what I could find that might be useful in lobbying for the young Tibetan’s release.

I came up with this article from the Measures for Carrying Out Medical Parole for Prisoners issued by the MOJ in 1990: “Prisoners who have contracted serious and chronic illnesses that have not been successfully treated for a long period of time…and who have served at least one-third of their fixed-term sentence” are eligible for medical parole. These measures were to provide the legal justification for Ngawang Choephel’s liberation and flight to the United States.

On April 19, 1999, a group of friends and I registered the Dui Hua Foundation as a 501c3 charity with the State of California Secretary of State. One week later, on April 26, 1999, the United States introduced a resolution critical of China at the Human Rights Commission’s meeting in Geneva. China mobilized its allies who together introduced a “no action” motion. This motion passed handily, prompting celebrations by Chinese officials and their allies. I received a fax from the MOJ advising me that, “for reasons known to all,” it would no longer provide responses to my requests for information on prisoners.

On May 7, 1999, NATO warplanes launched five US guided bombs at the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. The attack, organized and directed by the US Central Intelligence Agency, did extensive damage to the building, killed three Chinese journalists and wounded at least 20 other embassy staff. China was furious. Large crowds attacked and damaged the US embassy in Beijing, as well as other US diplomat posts in the country. A friend of mine who worked at the US consulate in Guangzhou was hit in the head with a brick.

I wrote to the Chinese embassy in Washington, expressing my regrets and enclosing a small donation for the families of those who were killed in the bombing. I received a letter from Li Zhaoqing thanking me. I was subsequently told that I was the only American who donated money to the families.

China cancelled virtually all programs with the United States, including the human rights dialogue. However, since Dui Hua’s dialogue had already been suspended, we were not affected. This enabled me to quickly resume talks with the Chinese government on prisoners. I flew to Beijing from Hong Kong in early September 1999, where I met with both the MOJ and the MFA as well as the China Society for Human Rights Studies. I handed over a list and received written information on several political prisoners. This was the first time Dui Hua submitted lists to the Chinese government.

In Washington, Senator Jeffords and members of the Vermont congressional delegation, including Congressman Bernie Sanders, continued to press Ambassador Li Zhaoxing to release Ngawang Choephel, or to at least treat him better. Their efforts began to pay off. In July 2000, Ngawang Choephel was moved from Powo Tramo Prison (aka Bomi Prison) in Tibet to Deyang Prison, a model prison in Chengdu, Sichuan Province. The next month, Ngawang was permitted two one-hour visits by his mother, Sonam Dekyi, and his uncle. The meetings were very emotional.

This gesture was likely related to an impending vote in Congress on granting China permanent Most Favored Nation, which had been renamed Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR). If that was the intent, the effort failed. On September 9, 2000, Senator Jeffords, a pro-trade Republican, voted no on the resolution to grant China PNTR. The motion passed 85-15. Jeffords’s vote made a big impression on Ambassador Li.

On September 11, 2001, planes hijacked by terrorists flew into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan and the Pentagon in Washington. A fourth attack, on the White House, was thwarted by passengers, forcing it to crash into a field in Pennsylvania. Chinese President Jiang Zemin went against the advice of advisors to distance China from the United States, and decided to do the opposite, He would use the terror attacks to bring China closer to the United States. But how to do so?

He summoned Li Zhaoqing, who had recently returned from Washington to become China’s foreign minister, for advice. Li advised Jiang that China should release high profile prisoners convicted of political crimes, starting with Ngawang Choephel.

A few weeks before the 9/11 terror attacks, I received a phone call from New York Times journalist Tina Rosenberg. Ms. Rosenberg was – and is – one of America’s most accomplished journalists having won a Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Award, and a MacArthur Fellowship. Ms. Rosenberg told me that she had begun writing a story on how businesses dealt with human rights abuses in countries where they did business. She wanted to tell my story as part of this article. (The story evolved into a cover story in the Times’ Sunday Magazine, Kamm’s List, that run in early March 2002.)

Tina began interviewing me over the phone and in person. The Times requested a visa for Ms. Rosenberg to visit Beijing to watch me at work. To my surprise she was granted one. A Chinese official told me “We don’t expect her to write a story like one that would appear in the Peking Review, but we hope she’ll be fair.”

Ms. Rosenberg and I took different flights to Beijing, where we met for dinner on December 17, 2001. In the following days she attended my meetings with the MFA and the Supreme Court, accompanied by a photographer. (The MOJ refused to allow Tina to attend our meeting. Nor was she allowed to accompany me on my visit to Beijing Number Two Prison on December 18.) The journalist did however attend a breakfast meeting with the American Chamber of Commerce. There she witnessed the chamber’s blunt rejection of my request for help.

The meetings with the MFA on December 18 and 19 took place at a critical time for my effort to help Ngawang Choephel. Writing of the December 18, 2021, meeting with the MFA. Ms. Rosenberg writes: “Kamm was nervous as we sat in the reception room of the enormous foreign ministry. Then, with a great flourish, in walked Li Zhaoxing, who had written the letter (to Senator Jeffords). He stayed only a minute and exchanged pleasantries, but Kamm had received the signal he was hoping for. Li Zhaoxing’s welcoming presence, if only for a moment, meant that Kamm’s concerns had been heard and that the release had been approved.”

After Zhao left, Director General Li Baodong agreed to a code name – “Mr. X. from Xanadu” – which facilitated my discussion about Choephel with Li Baodong on December 19, 2001. At that meeting we reached agreement on key points: Choephel would fly from Beijing to the United States, the US government would pay for his flight, and Ngawang Choephel was free to speak to the media on his time in Tibet and in prison in both the TAR and Sichuan.

One month later, on January 20, 2002, Ngawang Choephel, accompanied by an officer of the US Embassy, boarded Northwest Airlines flight NW88 to Detroit, arriving the same day. The MFA authorized me to release a statement on the release, which I did. According to the Dui Hua statement, “After receiving a medical examination and appropriate medical treatment in the United States, it is expected that Ngawang Choephel will return to India to be with his mother and other members of his family.”

The release of Ngawang Choephel marked the first time that China released a Tibetan political prisoner in response to foreign pressure. In the months after his release, other Tibetan prisoners were released, including Jigme Sangpo and the Drapchi nuns Ngawang Sangdrol and Phuntsong Nyidron. Sadly, Beijing no longer grants clemency to Tibetan political prisoners.

The lessons I learned during my work on the Choephel case formed a template for my human rights activism. These included:

- Close work with the US embassy in Beijing, and the Department of State in Washington. My partners were Ambassador Clark Randt and Assistant Secretary for Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor Lorne Craner.

- Close work with members of Congress, including Senator Jeffords. Senator Craig Thomas and others, including their staff.

- Coordination with human rights NGOs, including those working on Tibet. We insured that Ngawang’s name was on prisoner lists used in bilateral human rights dialogues, notably the dialogue between the United States and China that took place a few weeks before the release.

- Joint efforts with other governments, including Australia, which placed Ngawang Choephel’s name at the top of the short list of names submitted for their rights dialogue with China.

- Research into Chinese law. The “one-third” rule was deployed not only in the Choephel release, but in the releases of other dissidents.

- Outreach to audiences and media outlets.

Since his release in early 2002, Ngawang Choephel has continued his documentary filmmaking. His first film, Tibet in Song, was a Sundance Festival Jury Award Winner. Most recently, his movie, Ganden: A Joyful Land, debuted at the International Buddhist Film Festival in San Rafael, California, on April 30, 2023. Ngawang’s work has made an important contribution to preserving Tibetan culture and telling the story of the struggle for freedom of the Tibetan people.