<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

Download this story as PDF

Listen to Dragon Years: 2000 podcast episode.

Even before my first trips to China in early 1976, I frequented state-run bookstores. It was at the Commercial Press outlet in Hong Kong that I found On Exercising All-Round Dictatorship over the Bourgeoisie, the 1975 treatise by Zhang Chunqiao, theoretician of the Gang of Four. That booklet formed the basis for the purge of Deng Xiaoping and persecution of countless “bourgeois counterrevolutionaries.” Its removal from the Commercial Press bookstore in October 1976 was a sign that Zhang, Jiang Qing (Madame Mao), Yao Wenyuan, and Wang Hongwen, collectively known as the Gang of Four, had fallen from power.

For decades I visited bookstores in China, first to identify political and social trends, later to find cases to enter into Dui Hua databases from which prisoner lists were crafted.

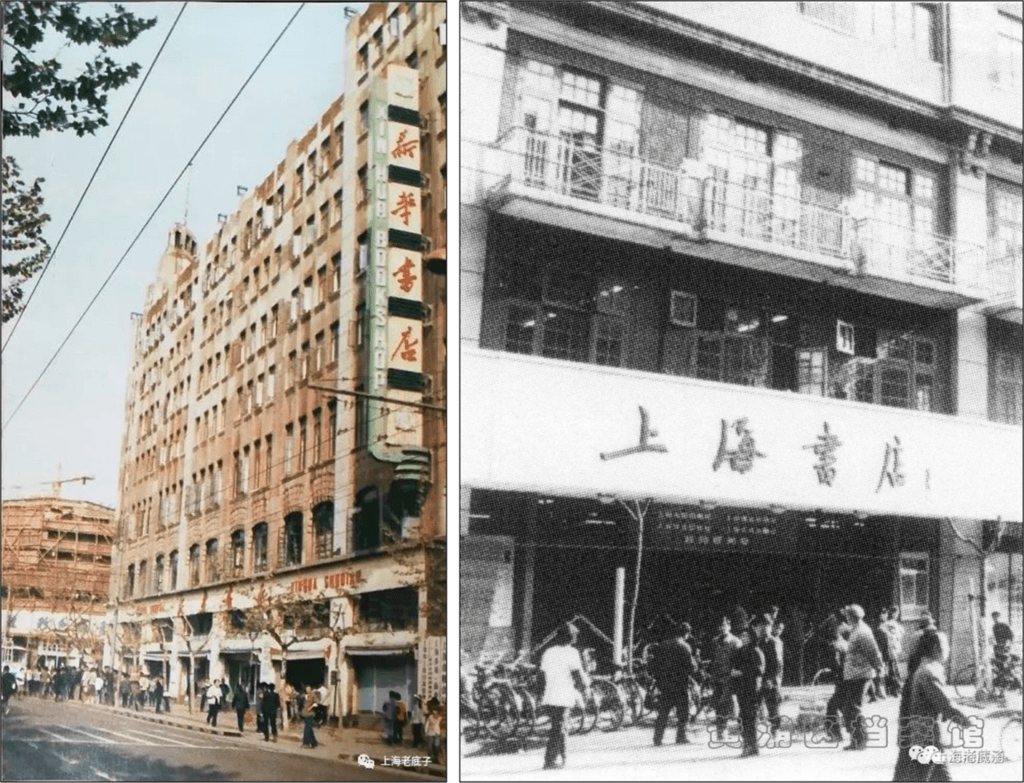

Shanghai

The morning after my arrival in Shanghai in January 1976, I walked to the Xinhua bookstore on Nanjing Road. It was a bitterly cold day, and the store was insulated from the weather by thick canvas curtains at the front door. I walked up the stairs to the second floor where I tried to enter the area where internal (neibu 内部) books were on display. I was told to leave. Later, upon my return, I was blocked from going upstairs.

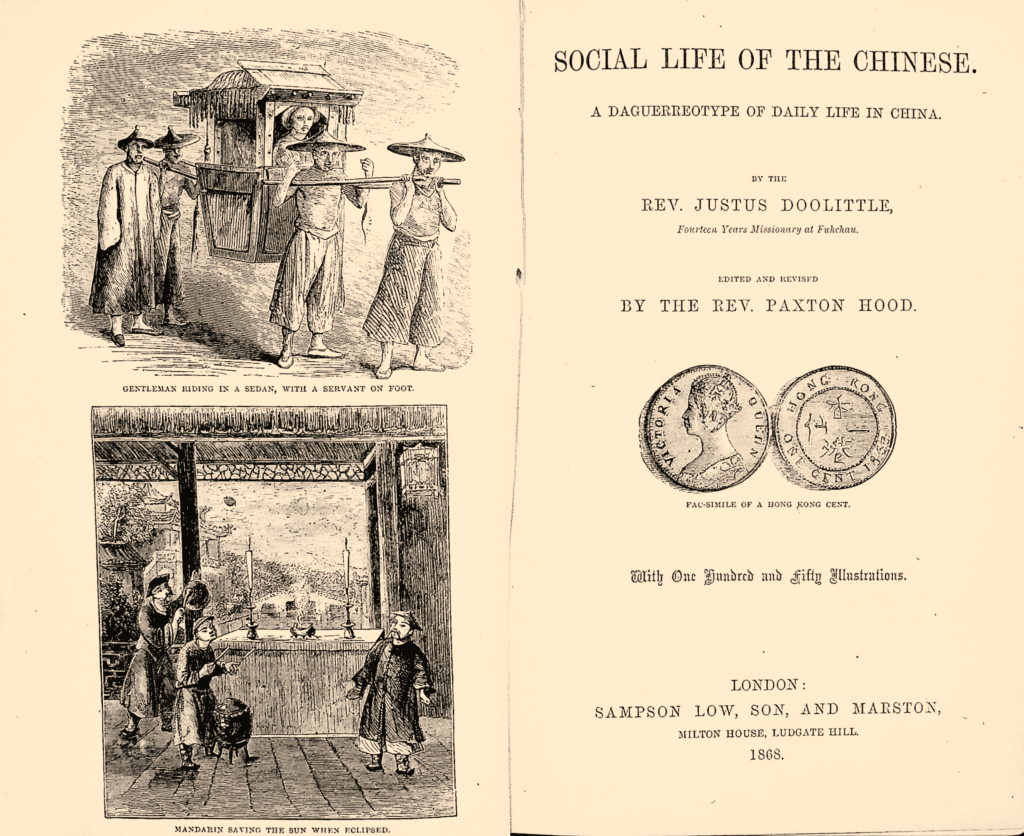

On future visits to Shanghai, I visited the Shanghai Bookstore on Fuzhou Road that sells secondhand books. I found a special bookstore on the grounds of the Jinjiang Hotel. There I found a trove of English-language books that had been taken from the libraries of European residents of Shanghai who had fled the city in 1949. I spirited more than 50 such books out of China, including Social Life of the Chinese by Justus Doolittle, first published in 1865. Such books are no longer available for sale in Shanghai.

Beijing

After attending the Feather and Down Fair in Shanghai, I flew to Beijing to attend the Fur Products Fair. I stayed at the Beijing (Peking) Hotel. Across the street from the hotel, on Wangfujing Avenue, stood a large Xinhua bookstore. Upon entering the store, one confronted an expansive display of Quotations from Chairman Mao, the Little Red Book, a staple of Cultural Revolution China.

On every trip to Beijing over the next two years, I paid a visit to the Xinhua bookstore. The display grew in size until 1978 when it was replaced by a display of books about Chinese law. Deng Xiaoping had been rehabilitated and Mao was in decline.

Further up Wangfujing, there was a Foreign Language Bookstore. It featured books by socialist writers who loved China, including New Zealand writer Rewi Alley. I purchased his Travels in China that covered the Cultural Revolution years of 1966 to 1971.

Further still was a second-hand bookstore in a market. It featured hard to find books published before the Cultural Revolution.

On my visits to the Supreme People’s Court, I passed by a bookstore that featured books published by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate. I found a volume entitled Selection of Criminal Cases: Counterrevolution. One of the cases covered in that volume was that of Zhang Chengjian (张成俭), a disgruntled farmer from Shandong Province who tried to set up an opposition party to oppose the Chinese Communist Party. He had been sentenced to death. I promptly added him to prisoner lists submitted to the Ministry of Justice. His sentence was commuted, and he received sentence reductions that resulted in his release from prison in April 2005.

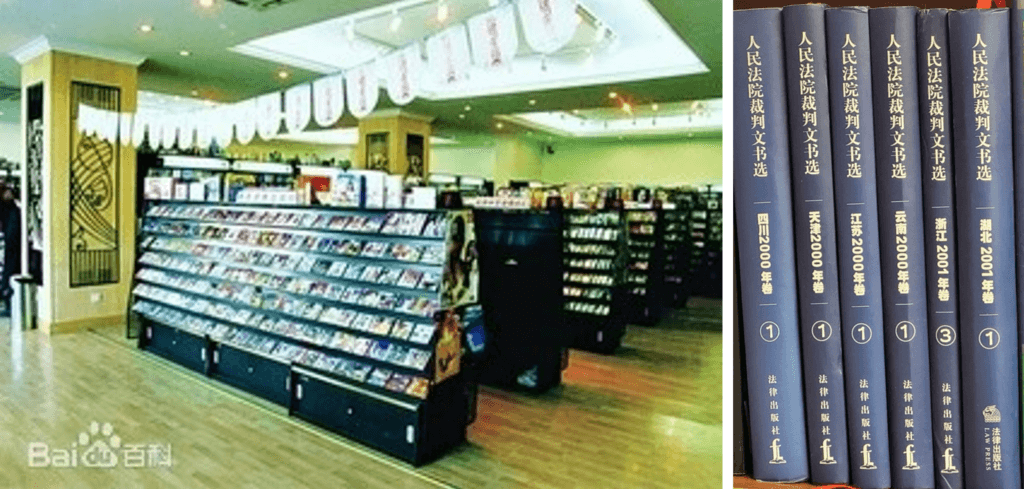

The most valuable bookstore for finding important volumes on political crime was the Law Press Bookstore, operated by the Ministry of Justice, an hour’s drive from my hotel. Among the volumes I found was a series of books that covered a selection of crimes, including endangering state security and so-called “cult” crimes, covered by Article 300 of the Criminal Law. Cases in those volumes included those of Yue Zhengzhong (岳正中), convicted of espionage by a Tianjin court; Lobsang Tenzin and Zege, two Tibetans convicted of splittism by a Sichuan court; Wang Meiping (王梅平), convicted of robbery and espionage by a Zhejiang court; and Kong Junlin (孔峻凌), convicted of subversion by a Hubei court.

It did not take long before volumes that interested me in Beijing bookstores were taken off the shelves. In recent years I had found nothing that would inform my work advocating for political and religious prisoners. I continued to find books on such topics as juvenile crime, the treatment of juvenile offenders, and how to apply for medical parole.

I grew concerned about what I would say to Chinese Customs if, upon exit from China, they found books marked neibu. I asked an interlocutor in the Chinese government. Her advice? Save the receipts!

My concern proved to be prescient. Shortly after this conversation, a buyer of used books marked neibu, a retired provincial archivist by the name of Jin Zhangqin (金章嵚), was arrested for trafficking in state secrets. Jin had purchased used and discarded books from two vendors in China and resold them to a research center in Hong Jong. He was tried, convicted, and sentenced to 10 years in prison. Dui Hua worked on his case. He was granted two sentence reductions and was released before the end of his sentence. More recently, the Ministry of State Security (MSS) announced in June 2024 that it had been tipped off by a collector of military books and documents that he had found more than 200 documents some of which were marked top secret in two bags outside a recycling center. The collector called the local MSS bureau which in turn arrested two men surnamed Guo and Li for violating China’s Law on Guarding State Secrets.

Tianjin

I attended the Carpet Fair in Tianjin in February 1976. The “Campaign to Beat Back the Right Deviationist Wind,” a thinly veiled attack on Deng Xiaoping and other “right deviationists,’” had begun. I was curious to see if I could find volumes that reflected the nascent campaign, so I hired a taxi and headed for the biggest Xinhua bookstore I could find.

As the taxi turned onto the street, it was as if an electric current had passed up the street. People began to assemble. Finally, the taxi arrived at the location. It was mobbed, faces pressed up against the glass. I struggled to exit the cab. The crowd followed me into the bookstore where they surrounded me. I left as quickly as I could, not having found anything of interest.

Even though Tianjin was and remains one the three most important ports in China, the crowd behaved as if it had never seen a foreigner. This was in sharp contrast to the people of Shanghai and Guangzhou who went about their business paying no mind to foreigners in their midst.

Guangzhou

I found little of interest in bookstores in Guangzhou. The Foreign Languages Bookstore carried a complete set of the works of Enver Hoxha, the Albanian dictator who was, for many years, China’s best friend in Europe. The works of Enver Hoxha had few buyers. They gathered dust until they were taken down.

As in the Foreign Language bookstore in Beijing, Enver Hoxha was not accompanied by the Works of Kim Il-Sung, the North Korean leader. This was another sign that Mr. Kim was not a favorite of Chinese officials based in or visiting Guangzhou for the bi-annual trade fairs.

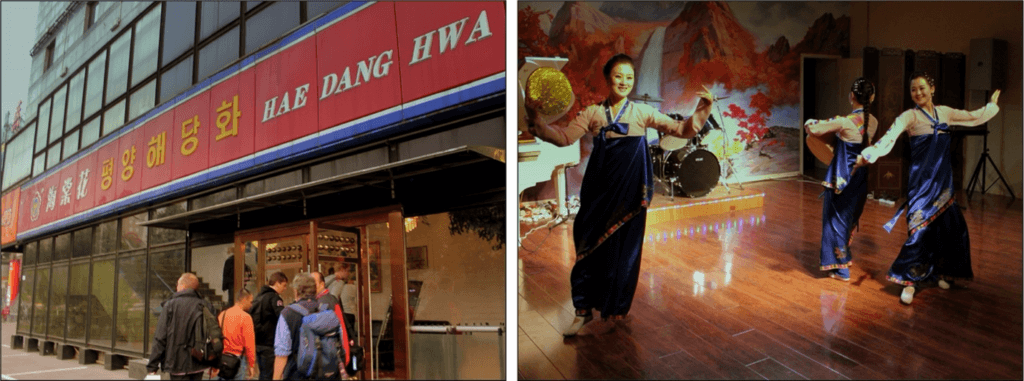

Pyongyang Jiegenghua Restaurant

In the early summer of 2013, as I went looking for a bookstore near the Beijing West Railway Station, I spied a Korean restaurant – Pyongyang Jiegenghua 平壤桔梗花 – with the windows papered over and large burly men guarding the door. I did some research and found out it was one of several North Korean restaurants in Beijing. (Many are now closed, including Jiegenghua.)

While they were operating, North Korean restaurants were a major source of foreign currency for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). According to North Korea Confidential, a revealing book by Damiel Pearson and James Pearson. At one time there were 40 North Korean restaurants in China, including many in Beijing.

While they were operating, North Korean restaurants were a major source of foreign currency for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). According to North Korea Confidential, a revealing book by Damiel Pearson and James Pearson. At one time there were 40 North Korean restaurants in China, including many in Beijing.

Mindful that American citizens were forbidden from spending money that might benefit Pyongyang, I asked a local Chinese friend to accompany me to Jiegenghua, promising to reimburse him after the visit.

What we found upon entering was a space from a different world. Dark and forbidding, with young Korean women serving tables. Propaganda posters adorned the walls.

I wondered aloud who the waitresses were. My friend, who understood and spoke English perfectly, overheard me and offered an answer. It turned out he was familiar with North Korean restaurants and had frequented them over the years. He was an afficionado of Korean food and Korean alcoholic beverages.

“The young women are the daughters of high-ranking government and party officials who live in Pyongyang,” he replied. “They spend a year in this place and are not allowed to walk around outside.”

He continued: “It is considered a great honor to be selected to serve tables at North Korean restaurants in Beijing. All the money earned – including tips – goes straight to the government in Pyongyang. It sometimes happens that the women form close relationships with Chinese officials and businessmen in Beijing. They give the women expensive gifts – watches and gold bars. These too must be surrendered upon their return to Pyongyang.”

We sat at a table with a group of Chinese businessmen who had just gotten back to Beijing from Pyongyang. They were clearly happy to be back home. One of them had drunk far too much North Korean fiery liquor. His head sank until it landed in a bowl of kimchi.

As we sat at the table, my friend saw a People’s Liberation Army officer come in with an aide carrying his briefcase. My friend recognized him and muttered, “This man is a corrupt officer.”

I was invited to go to the second floor to meet the ladies who were entertaining guests. I passed on the opportunity. Sometimes, discretion is truly the better part of valor.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.