What has influenced Dui Hua’s approach to human rights diplomacy in China? Travel and business. In On the Road in Guangdong Province, Executive Director John Kamm describes the encounters that would inform his human rights work in China.

Ten years before I began travelling to Guangdong Province to sell provincial authorities on the virtues of releasing political and religious prisoners, I was traveling the length and breadth of the province selling something different: agricultural and industrial chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and chemical technology.

Even before travelling around the province selling chemicals, I was attending the biannual trade fairs in Guangzhou, the Chinese Export Commodities Fair. I attended 10 fairs, from 1976 to 1980. At these events, the trade fair authorities would lay on trips to locations in the Guangzhou suburbs. I joined as many of these trips as possible, visiting a commune that grew tea in Hua County, fireworks factories in Dongguan County, and the Birds’ Paradise outside of Jiangmen.

Fort Bayard

At the end of the nineteenth century, European powers set about carving up China in what came to be known as “The Scramble for Concessions.” The United Kingdom leased Weihaiwei in Shandong Province and much of Baoan County in Guangdong Province, Germany grabbed Qingdao, Russia acquired Port Arthur (now Dalian), and France leased Kwangchowwan. The capital of the territory was Fort Bayard, now Zhanjiang. Kwangchowwan was administered as a part of French Indochina from 1898 to 1943.

Zhanjiang Prefecture is one of China’s biggest producers of peanuts. In the late 1970s and well into the1980s, Zhanjiang’s peanut crop was badly affected by fungal diseases. I had secured the China agency of Diamond Shamrock Chemical in July,1979. Diamond Shamrock Chemical produced Daconil, a highly effective fungicide.

In May 1980, I gathered a team of experts to travel to Guangzhou to promote the use of Daconil. We gave a technical seminar, conducted a field trial on peanuts at a commune in the Guangzhou area, and met with representatives of foreign trade corporations and users, including the provincial State Farm Bureau and the Overseas Chinese State Farm Bureau (华侨农场). The Overseas Chinese Farms were established to resettle Chinese refugees and migrants from Southeast Asia, starting in the 1950s. After the discussion, we selected an Overseas Chinese state farm in Zhanjiang and set out in a minibus (called a “bread car 面包车” by the locals because they were shaped like a loaf of bread and minibus sounds like mian-bao in Cantonese) on the morning of Saturday, May 31, 1980.

Traveling by road in Guangdong Province was hazardous. Drivers made liberal use of their horns, especially when overtaking other cars. Approaching cars would turn on their high beams at night, blinding the driver and occupants of the oncoming vehicles. The solution was turning on your own beams to blind the other driver, or pulling over to the side of the road till the other car passed. The latter maneuver resulted in more time on the road. I lost two good friends to accidents caused by reckless drivers whose sole qualification for a driver’s license was passing a vision test.

The distance by road between Guangzhou, where Diamond Shamrock had an office, and Zhanjiang is 420 kilometers. Today, traveling the distance by car takes four and a half hours. In 1980, it took much longer and involved several crossings of the West River by ferry.

After finding the bureau and calling the state farm to get directions, we arrived at the state farm in the early hours of June 1, 1980, and settled into where we’d be staying for the week. It was not a welcoming environment. Our housing had been used as a refuse dump.

Not long after we settled down to sleep, we were awakened by revolutionary songs to march and perform calisthenics to. Breakfast consisted of steamed buns and congee. As soon as we could, we left for the city to have a look at the old French concession.

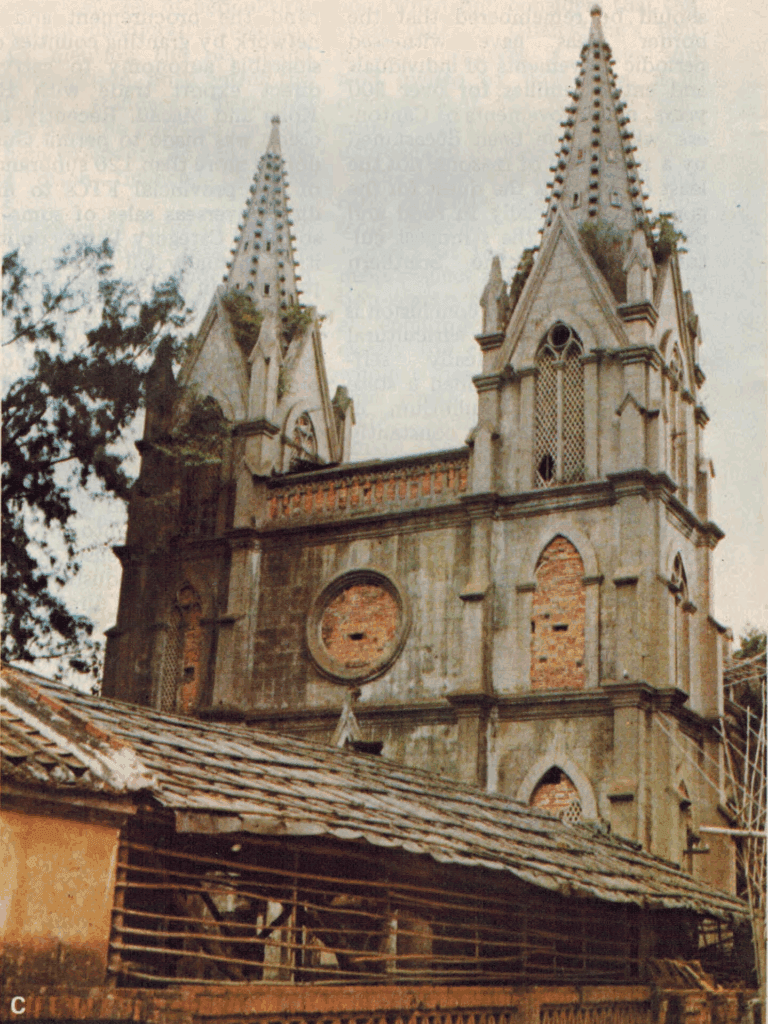

What we saw were the dilapidated remains of a small colonial settlement. Border posts, once manned by the French Foreign Legion, were choked with weeds. Offices of French officials were falling apart. The windows of the Cathedral of Saint Victor were bricked over. I managed to have a look inside. The pews had been taken out and replaced by rusting machine tools.

The priests of St. Victor’s acquiesced in the decision of the revolutionary committee to transform the church into a factory. The priests at another Catholic Church in the area refused to do so, believing that the committee’s order was sacrilegious. That church was then torn down by zealous Red Guards.

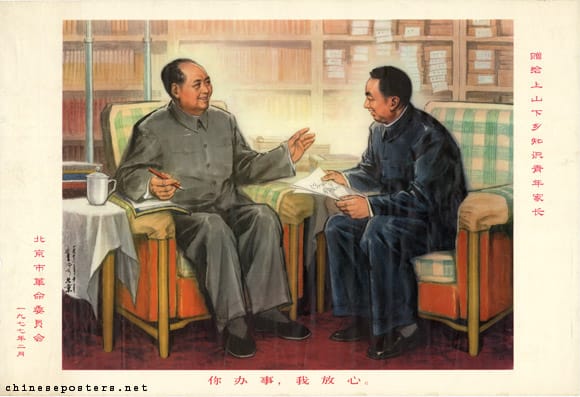

The Overseas Chinese State Farm where we conducted the Daconil trial abutted old Fort Bayard. A customs station, manned by French legionnaires had been erected (Fort Bayard had been used to smuggle opium and other contraband into China). In 1980, the exterior of the station was taken up by a private market where farmers sold what they grew or raised on their private plots. Looming over the market was a large brick and concrete hoarding with a poster of Chairman Mao speaking to Hua Guofeng: “With you in charge, I am at ease. 你办事,我放心。”

We expected that the farm workers would help us spray the peanuts with our fungicide. They helped but we wound up doing much of the work ourselves. We paid a hefty fee for the pleasure of working with their workers and using the state farm soil.

We handed out samples of shirts and hats. Fortunately, our hats were blue. (Another agricultural chemical company handed out green hats but was mystified by the farmers’ refusal to wear them. Wearing a green hat carries a very negative connation. It means your wife or girlfriend is cheating on you.)

Later we tried spraying Daconil on rubber trees at a state farm in Hainan. The trials failed. The fungicide was no good on old rubber trees.

Although we eventually sold small quantities of Daconil to Chinese foreign trade corporations, we never hit pay dirt. Unbeknownst to us at the time, Chinese scientists worked hard to reverse engineer Daconil and produce China’s own Daconil. Unfortunately, the manufacturing process they used was highly carcinogenic. Workers died.

Finding Arsenic Trioxide

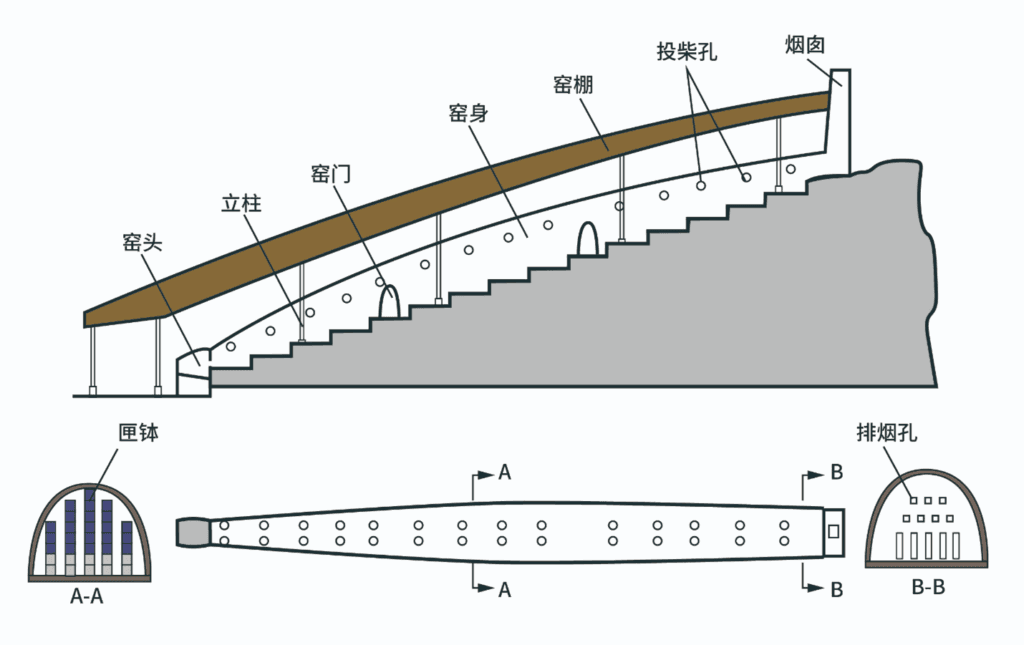

My team and I were tasked by Diamond Shamrock to find sources of arsenic trioxide, a deadly powder used to manufacture weed killers. We ventured to two remote locations in Guangdong Province, Yunfu County in the western part of the province, and Yangshan County in the northern part. In these places we witnessed arsenic being refined in so-called “dragon kilns,” a technology developed in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD.)

On the trip to Yunfu, I travelled with Bill Mulligan, a mining engineer who worked for a large New York bank. We drove over rough roads. In striking contrast, the next county to the west was Loding, a national model in road building. At a later date I traveled on those roads: wide, paved, with barriers on the side and signage in good sight.

Accompanied by county officials, we hiked up a steep hill until we reached a ridge, where we could peer down at the countryside below, dotted with abandoned mines where arsenic-laden rocks had been mined, tailings leaching out from the mouths of the mine.

We stopped for a cup of tea. The county boss remarked that the tea plants were the only thing that could grow in the arsenic-laden soil. We immediately spat out the tea, but Mulligan asked for a bag of what we called “arsenic tea,” which he was given. Turning to me, he said, in a low and joking voice, “I’ll bring this home and give it to an in-law!

We moved closer to the dragon kiln. Village women were hauling buckets of arsenic trioxide down the trail back to town. No special protection gear was worn, no special procedures were followed. I took short breaths but nevertheless felt a tightening of my windpipe in my upper chest.

Selling Vaccines to Pigeon Farms

One of the companies we represented was a European manufacturer of vaccines for animals, especially poultry, flocks of which were frequently ravaged by avian diseases. We ventured to Zhongshan County north of Macau, there to conduct a technical exchange on vaccines for pigeons. Zhongshan is famous for its “Shekki Pigeons,” named after Zhongshan County’s seat, Shiqi (Shekki in Cantonese). These birds, roasted in a time-honored way that results in succulent meat and crispy skin, fetch high prices in Hong Kong and Macau.

On the same trip we introduced a Swiss product to counter swine flu, a perennial problem in South China.

The pigeon exchange was a complete success. County officials, who had their own stash of US dollars, wanted to buy the vaccines from us, but wanted to do so quickly rather than going through the provincial foreign trade corporation.

We decided to use their standard Chinese-language contract used to buy things from mainland companies. Things moved quickly. We signed the contract, the county corporation opened the letter of credit for US$ 30,000, and we arranged the shipment in refrigerated containers. This transaction is believed to be the first sale to a county foreign trade company (known as “sub-branches”) during the reform and opening period.

My experiences doing business, particularly in Guangdong Province, prepared me for my human rights work. I re-learned what my father taught me about selling: Know your customer well, know what your customer wants, and know what your customer is willing to pay. This holds true whether it’s selling chemicals or selling ideas like the benefit of releasing prisoners.

I also learned that, while the outcome of major political cases is determined at the highest level in Beijing, many cases are handled by local government and party officials including those in prison bureaus, courts, and procuratorates. Today, most of the information on political prisoners that Dui Hua obtains is provided by local entities, bypassing Beijing. Sentence reductions and other acts of clemency are frequently decided at the local level … just like business transactions.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.