<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

In 1976, China was gripped by ideological fervor. John Kamm, Hong Kong representative of the National Council for US-China Trade, began attending mini-fairs in mainland China in January that same year. A journalist, researcher, and trade promoter, Kamm was in a unique position to witness China in flux, rife with contradictions and tensions — between past and present, East and West, tradition and modernity. As a two-part look back on those years in Guangzhou, this instalment of John Kamm Remembers focuses on those trade fairs, his China trade publications and efforts as a trade promoter.

S

alesmanship is the art of convincing people to buy something they don’t think they need, whether it’s chemicals or human rights.

I learned how to sell from my father, who sold whiskey and beer for the Trenton Beverage Company in the 1950s and 1960s. He was, in his words, a purveyor of alcoholic beverages.

I would watch him ply his trade as he covered his sales route in central New Jersey. Salesmanship enabled me to embark on my journey of becoming first a journalist, then a businessman, and finally a human rights advocate.

I started writing about business in China in 1975 as an assistant editor of Asian Business and Industry, a monthly magazine published by Far East Trade Press in Hong Kong. In 1976, after being appointed the Hong Kong representative of the National Council for US-China Trade (“National Council”) I began promoting trade with China by attending “mini-trade fairs” in Shanghai (Feather and Down) and Beijing (Fur) in January, and Tianjin (Carpets) in February.

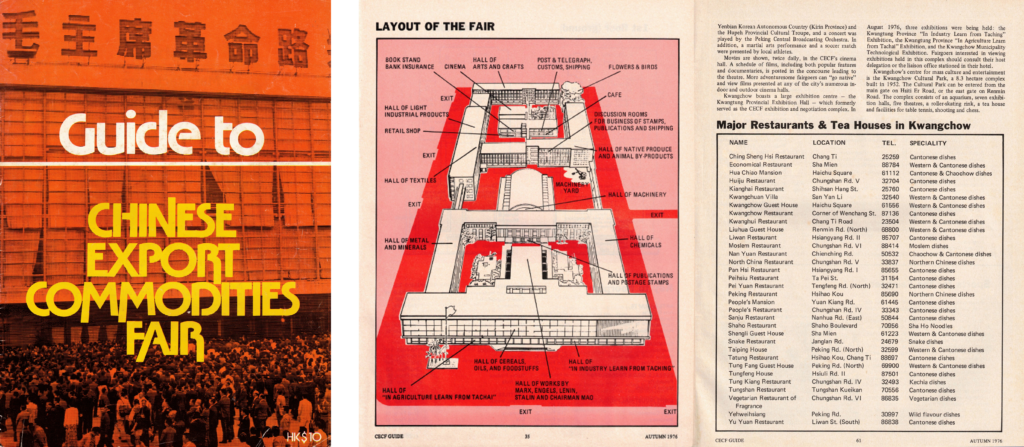

Back then, trade fairs served as a rare window of opportunity for foreigners to enter China, and my work there led to many poignant and memorable moments, such as attending China’s Premier Zhou Enlai’s funeral in Beijing in January 1976 and getting caught in the devastating Tangshan Earthquake in July, while travelling to the Chemicals Trade Fair in Tianjin. In 1976 and 1977, I attended the Spring and Autumn Export Commodities Fairs in Guangzhou, also known as the Canton Trade Fair. Seizing the opportunity, my wife and I led a small team of writers to put together the Guide to Chinese Export Commodities Fair, a publication that would serve as a guide to the trade fair for foreigners. With the help of the Far East Trade Press, it was published in time for the 1976 autumn trade fair.

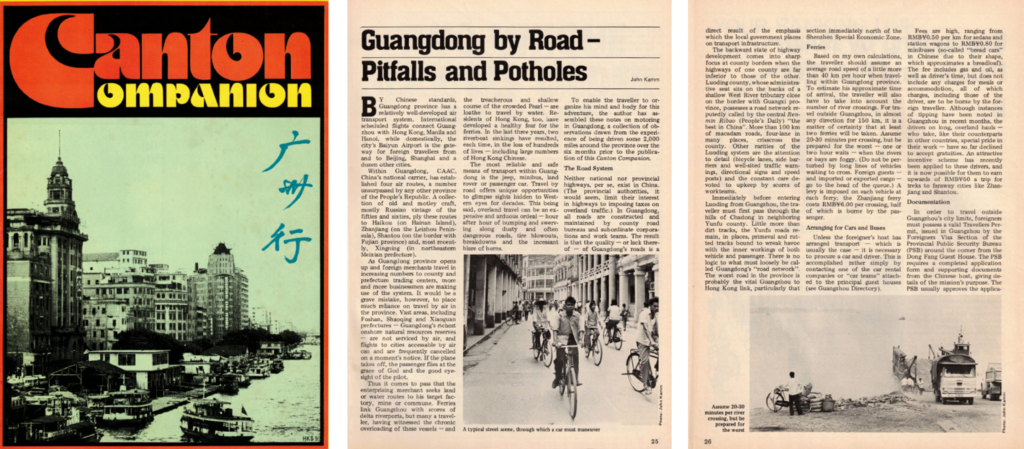

This was followed by Guide to Canton for the spring 1977 fair and, subsequently by Canton Companion for the next six biannual fairs. I also started working on in depth business and trade reports including the China Trade Quarterly and the China Economic Times.

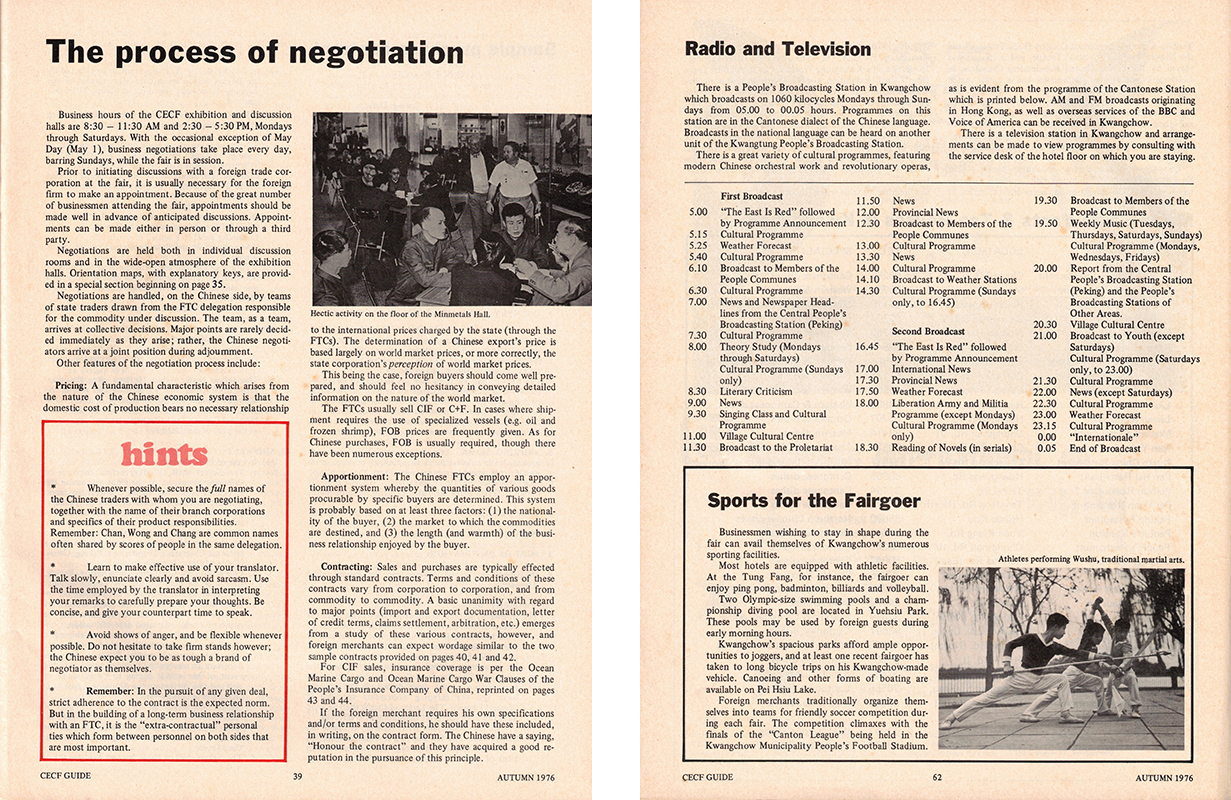

We had to haul hundreds of copies of these magazines and equipment across the border from Hong Kong, passing through the border town Shenzhen where the crates, more than 40, were opened and inspected by Chinese Customs. Upon arrival in Guangzhou, we settled into the National Council’s office on the seventh floor of the Dongfang Hotel, which would serve as our residence for five-week stays. We then unpacked the boxes and set up the office in time for the opening of the fairs, which ran from April 15 – May 15 and October 15 – November 15, respectively.

On the eighth floor of the hotel was the storied “Top of the Fang,” a brightly lit place with tables covered by white cloths. It served soft drinks and cold beer, notably Tsingtao beer, and offered peanuts. Tipping was not allowed (and was considered insulting to the staff who viewed their work there as service to the people). A jar full of Chinese coins and bank notes was placed at the entrance for errant tippers to reclaim their money.

The Council’s office was equipped with an IBM electric typewriter, a Xerox 660 copier, and a telex tape-punching machine. The office was well-stocked with soft drinks, beer, and spirits. To send a telex, we would go to the ground floor, punch a tape, and wait in line until a telex machine became available. Occasionally, we visited offices of foreign trade corporations in downtown Guangzhou. Most were dark, cold, and damp.

Canton Companion

Publications released by Far East Trade Press for the trade fairs turned out to be hits: not only were they the only English-language publications covering the trade fair, they were also one of the few English-language publications distributed, on a limited basis, in China. Back then, we were in the waning days of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution*, a period of turmoil that damaged many facets of life in China including the economy and the conduct of foreign trade. To the lucky few businesspeople able to make it into China for the trade fairs, the twice-yearly magazine was a lifesaver, not only for its advice on accessing essentials like making phone calls, finding food, etc., but also for offering insights into the oddities of Cultural Revolution-era culture.

Besides services on offer in Guangzhou, Canton Companion featured articles on topics like Cantonese opera and dissent in Guangzhou where the “counterrevolutionary Li Yizhe group” was based. The group consisted of a few dozen local dissidents led by Li Zhengtian.” It was “struggled” in sessions at a theater near the train station, served long sentences in prison, and were nearly executed for their 1974 big character poster calling for democracy and rule of law. Mao Zedong is said to have intervened. He famously said “We should not fear criticism. The sky won’t fall.”

Sourcing basic information for Canton Companion was a daunting task: many publications were deemed to include state secrets. Local newspapers could not be read by foreigners; photographing locals reading them was forbidden. (I once heard of an Australian couple detained in Shanghai in 1976 for photographing locals reading a newspaper on a small glass-enclosed billboard).

The contents of the Guangzhou phone book – the phone numbers – were also considered state secrets. Every floor of the hotel had a copy of the phone book at the reception desk in a locked drawer that was often kept open. I stole furtive glances and memorized the numbers of foreign trade corporations. There were no private phones in Guangzhou in those days and the numbers for state enterprises, including for branches of foreign trade corporations, consisted of five digits.

While Canton Companion was distributed free of charge, it was supported by advertisements of companies doing business at the trade fair. This was yet another practice unheard of during the height of the Cultural Revolution. As an agent for chemical company Diamond Shamrock, my company Primary Sources placed an advertisement in a local newspaper – the Guangzhou Daily – on April 14, 1979. This was one of my team’s greatest achievements

Liaison offices, staffed by foreign affairs and public security officers, were established in each hotel housing foreigners during the trade fair (the Dongfang Hotel for most Western foreigners; the Baiyun Hotel for the Japanese and the Guangzhou Hotel on Haizhu Square for Hong Kong businesspeople). One job of the liaison offices, besides registering the attendees, was to organize visits to places of interest inside and outside Guangzhou. I availed myself of chances to go on these excursions, visiting people’s communes, tea farms, factories, hospitals, and other locales. By the time I stopped attending the trade fairs in the 1980s, I had visited most of the counties in Guangdong Province.

I experienced both humorous and terrifying events on these travels. On one trip to a commune in Zhanjiang, I came across an elderly man early one morning. My colleagues and I needed to call the commune management to let them know we’d arrived and to get directions. The fellow would dial a number and immediately hang up the phone. On another trip to the hinterlands, we found out why driving at night on Guangdong roads was so hazardous. Many drivers, who got their licenses by merely passing a vision test, would turn their headlights on high beams and then suddenly turn them off. Back and forth, from blinding lights to total darkness.

After my company, Primary Sources, secured the agency for Diamond Shamrock in 1979, I began travelling to remote corners of Guangdong Province to find raw materials for Diamond’s products. The company produced a herbicide based on arsenic trioxide. In Guangdong, two counties – Yunfu and Yangshan – had large reserves of arsenic, mined and roasted in traditional dragon kilns. Primary Sources colleagues made three trips to these counties, during which there were several humorous adventures.

On my visit to Zhongshan, I worked with a Swiss vaccine manufacturer to quell an epidemic of pigeon flu. The trial was a success and resulted in the first-known sale of a foreign product to a sub-provincial foreign trade corporation.

In addition to trips to Yunfu and Yangshan, I visited communes, state farms, ports, and factories in Jiangmen, Zhanjiang, Hainan (then part of Guangdong Province, now a separate province), Zhongshan, Zhuhai, Dongguan, Luoding, Yunfu (said to have the best roads in China – “in building roads, learn from Yunfu!”), Whampoa, and Baoan (now Shenzhen). These places were rarely visited by foreigners.

Although the trade fairs were primarily venues for cutting export contracts, two commodities were purchased in large quantities: plastic resins and industrial chemicals. I met representatives of American chemical firms and in 1979 when the United States and China reestablished relations, I took on the agencies of several companies, most importantly Diamond Shamrock, based in Cleveland, Ohio.

I opened the first foreign office in Guangzhou, well before regulations governing the establishment of foreign offices were promulgated. Beijing was often unaware of what was happening in the southern city. As the saying goes, “The mountains are high, the emperor is far away.”

I finally got to use what my father taught me: I became a salesman.

*Note: While there is general agreement that the Cultural Revolution began in 1966, there is no general agreement on when it ended. A leading authority on the Cultural Revolution in the West, Professor Fred Teiwes, has laid out four possible dates in the 1968-1978 period. Professor Teiwes and other experts date the end of the Cultural Revolution to 1966-1968, when the worst excesses took place. For this episode of John Kamm Remembers, I take the end of 1977, when Deng Xiaoping was rehabilitated, as the culmination of the Cultural Revolution.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.