Shortly after Tibetan political prisoner Ngawang Sangdrol’s arrival in the United States on March 28, 2003, I began preparing for my next visit to Beijing and Hong Kong, tentatively scheduled for early June, roughly four weeks later. Preparations for these visits, then as of now, take many weeks.

Cases need to be identified, researched, and prioritized. Bilingual prisoner lists for my interlocutors have to be prepared. For this trip I intended to focus on the imprisoned American businessmen Jude Shao and Fong Fuming, as well as prominent Uyghur political prisoner Rebiya Kadeer.

I sought meetings with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Justice, the Supreme People’s Court, the Supreme People’s Procurement, and leading Chinese academics who served as advisers to the Chinese government. I asked to visit a prison. I asked for meetings with the American ambassador and other diplomats as well.

I made my preparations with some trepidation. A fatal disease – Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) – was sweeping China. Thousands of infections had been recorded, and many people – including officials – had been placed under quarantine. Guangdong Province was especially hard hit. By early June 2003, the province had recorded more than 1,500 cases and 57 fatalities. SARS had already spread to Beijing, Tianjin, and other provinces and municipalities by April. By early June, there were 5,329 cases and 336 reported deaths nation-wide.

The epidemic reached Hong Kong in March 2003. The first fatality was recorded on March 11. By early June, 1,750 cases had been identified and 286 deaths recorded. The city was in a state of high alert. Disinfectant was applied liberally to every conceivable surface, often several times a day. People wore masks and generally avoided public gatherings. Tourist arrivals dropped precipitously.

In mid-May I was advised that my principal interlocutor, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Director General of the International Department Li Baodong, remained under quarantine. All prisons in the country had been placed off limits to visitors. I decided to cancel my trip to Beijing but to proceed with the visit to Hong Kong. I would meet Chinese officials from an inland province as well as Hong Kong activists, academics, and researchers. As usual, I would conduct research at the University Services Center of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

“Nest of Spies”

SARS was not the only issue troubling the people of Hong Kong during the early months of 2003. Article 23 of the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, stated that the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) “shall enact laws on its own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People’s Government.” This article had been inserted into the Basic Law after the events of May and June 1989 in Beijing.

By late 2002, the SAR’s Legislative Council (Legco) had failed to enact the legislation called for under Article 23, and Beijing was growing impatient. Chinese officials based in the SAR declared that Hong Kong was a nest of spies; in early 2003 at least three Hong Kong residents, all of whom had worked in China’s Xinhua News Agency, were detained in Guangdong Province for allegedly spying for the United Kingdom during the years leading up to the handover in 1997. They were eventually arrested, tried, and convicted of espionage. Two of them, Chen Yulin and Wei Pingyuan, were sentenced to life in prison. They were still in prison, despite multiple sentence reductions, as of mid-2018 (see this issue’s Prisoner Update).

The Hong Kong official tasked with pushing through Article 23 legislation by Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa was Regina Ip, a career civil servant holding various positions in the Hong Kong government before being appointed Secretary for Security in July 1998. Ms. Ip and I had worked on retaining Most Favored Nation trading status for China in the early 1990s. I knew her as a tough, uncompromising official well versed in issues of trade, industry, and immigration. She had little knowledge of national security however, and had infrequently visited China before 1997 (when she was 47 years old). This was in line with pre-handover British policy which placed restrictions on Hong Kong officials traveling to the People’s Republic.

Regina Ip was also very ambitious. She was determined to eventually become the Chief Executive of the SAR.

Unfortunately for her ambitions, Secretary Ip had developed a reputation for alienating people by making ill-considered remarks. In the run-up to the introduction of the National Security Bill in the Legislative Council’s Bills Committee on February 14, 2003, Secretary Ip had warned against viewing democracy as a panacea. After all, she said, Adolf Hitler had been democratically elected as Germany’s chancellor before embarking on his murderous genocide directed at the Jews. She also disparaged Hong Kong’s taxi drivers and restaurant workers, opining that they weren’t interested in such things as national security.

A Letter from Alan Leong

I arrived in Hong Kong on June 11 and immediately went to the J.W. Marriott Hotel at Pacific Place on Hong Kong Island. After checking in, I went to my room to begin unpacking. While doing so, I noticed a letter that had been slipped under my door. It was from Alan Leong, a leading member of the Article 23 Concern Group and Chairman of the Hong Kong Bar Association. The letter, on Bar Association stationary, invited me to make a presentation to a conference on Article 23 to be held at the Law School of Hong Kong University on June 14-15, 2003. The title of the conference was “Freedom and National Security – Has the Right Balance Been Struck?” I was asked to make a presentation on national security legislation in the People’s Republic of China.

I called Mr. Leong at his Chambers. “What’s this all about?” I asked. “The policy governing Hong Kong is ‘One Country, Two Systems.’ What does national security legislation in China have to do with national security legislation in Hong Kong.” At that point I hadn’t even read the National Security Bill being considered by Legco.

Mr. Leong replied, “You are correct. National security legislation in China should have nothing to do with national security legislation in Hong Kong. As it turns out, however, the bill under consideration contains language which links the two systems. In short, if an organization in Hong Kong is subordinate to an organization in China that has been banned by the central government on national security grounds by means of a certificate, the Secretary for Security can ban it in Hong Kong.”

I was intrigued. I had never heard of a Mainland Chinese mechanism for banning an organization on national security grounds by means of a certificate. Prior to 1997, when China’s Criminal Law was amended to remove the crime of counterrevolution, individuals could be sentenced to prison for simply belonging to a counterrevolutionary group. Whether or not a group was a counterrevolutionary group was determined by a court, not by a government agency. After 1997, mere membership in a group no longer constituted a crime. This important 1997 reform of the Criminal Law sought to criminalize acts like drafting manifestos and raising money, not simple association.

I agreed to make a presentation on June 15, the second and last day of the conference. I was told by Mr. Leong that the audience would probably be small. June 15 was Father’s Day in Hong Kong, and mine would be among the last presentations.

After we rang off, I went to the hotel’s concierge level and printed out a copy of the National Security Bill. Part 4, Section 8A (2) (c) provided for the Secretary for Security to proscribe any local organization “which is subordinate to a mainland organization the operation of which has been prohibited on the ground of protecting the security of the People’s Republic of China, as officially proclaimed by means of an open decree, by the Central Authorities under the law of the People’s Republic of China.” The next section (3) stated that conclusive evidence of the prohibition would be “a certificate issued by or on behalf of the Central People’s Government.”

I began preparing a presentation based on points of Chinese law, and on cases of individuals tried by Chinese courts for counterrevolution and endangering state security.

The Conference

I decided not to attend the first day of the Hong Kong University conference on June 14, 2003. That evening though, I was invited to attend a dinner at the Hong Kong Club. In attendance were conference participants including local pro-democracy activists and lawmakers. The mood was grim.

Earlier that day Legco’s Bills Committee had carried out a “clause by clause” review of the National Security Bill, a process that took nearly eight hours. Many of the legislators in the democratic camp chose not to attend the meeting, preferring to attend the Hong Kong University conference instead. After the review, the Legco committee voted to end debate, meaning that debate could not be reopened, and easing the way for the bill’s adoption by Legco.

All seemed lost. What could be done to stop adoption of the legislation by Legco? I weighed in at the dinner, introducing the Cultural Revolution concept of “raising the red flag to oppose the red flag.” It was often used by Red Guard factions against each other; each claimed the mantle of Mao Zedong thought and used quotations from Mao to undermine the arguments of the faction.

In the case of Article 23, Chinese law was a “red flag,” and set against this was another “red flag,” the Hong Kong National Security Bill. What we needed to do was to show how the Hong Kong legislation ran counter to both the spirit and letter of Mainland Chinese law. Instead of pointing out why the legislation was bad for the human rights of the people of Hong Kong, basing our arguments on the Common Law, we needed to show how the legislation was bad for the people of China based on Chinese law. A long shot, but worth a try.

The next day I arrived at the conference hall to find a packed room of leading legal scholars from around the world, a cohort of Democratic legislators, and the Hong Kong Solicitor General Bob Allcock and his subordinates. Mr. Allcock was head of the Legal Policy Division of the SAR Department of Justice.

My panel sat down and shortly thereafter I began my presentation. I went through it point by point, focusing on the 1997 amendment to the Criminal Law that criminalized acts, not association.

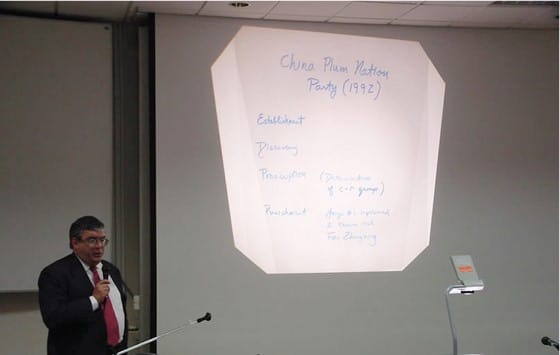

I referenced several cases in which individuals had been convicted of subversion after 1997 for undertaking subversive acts. I had been unable to find a single case of someone being subjected to coercive measures for mere membership in an organization. In one case, that of the Chinese Nation’s People’s Party, more than a thousand members of an underground political party had been spared criminal prosecution. Its leaders had been convicted of subversion and sentenced to long prison terms for engaging in activities like organizing meetings, drawing up a manifesto, and raising money.

Reinforcing my point that China did not ban groups on national security groups, I pointed out that it had in fact banned groups like Falun Gong on public order grounds. Article 300 of the Criminal Law made it a crime, punishable by imprisonment, to use a cult to disrupt the administration of the law. If China had banned groups on public order grounds, why hadn’t it banned groups on national security grounds?

I concluded that Hong Kong’s National Security Legislation could not come into force unless and until China’s National People’s Congress amended the criminal law and returned to the “bad old days” of the pre-1997 criminal law, a time-consuming and complicated process that would anger China’s legal reformers who were proud of having removed “membership in a counterrevolutionary group” from the criminal law.

My remarks caused quite a stir. Veteran democratic legislator Martin Lee wondered aloud: “Why didn’t we think of that?” Legislator and union leader Lee Cheukyan delivered impassioned remarks: “We Hong Kong people are so selfish. All this time we have been concerned with how this bill will hurt the human rights of the Hong Kong people. Now we learn that it could hurt the human rights of the entire Chinese nation. We will be condemned as criminals for a thousand generations!”

At this point, Attorney General Allcock addressed me, arguing that there were regulations issued by local authorities that governed registration of organizations. If an organization could not be registered, it was the same as banning the organization. I disputed this. “Refusing to register an organization is not the same as banning it. And, in any event, laws passed by the National People’s Congress take precedence over regulations put out by ministries and local governments. There is nothing in the Criminal Law about banning organizations on national security grounds.”

Albert Chan took the floor. Chan, former dean and current professor of law at Hong Kong University School of Law and a member of the Basic Law Committee, was a respected legal scholar enjoying excellent relations with senior Chinese judicial and government officials. “John Kamm is right,” Professor Chan declared. “For the National Security Bill to be enacted in its present form, Mainland Chinese law would have to be amended. No proscription mechanism as described in the bill exists in Chinese law.”

Bob Allcock was at sixes and nines, the proverbial deer in the headlights. He had lost control of the meeting. He said that the issue I had raised could be discussed at the Legco Bills Committee meeting on June 17. I asked if I could attend the meeting and he said yes.

The next day local newspapers, English and Chinese, were full of stories on what I had done. A headline in the South China Morning Post read “Hong Kong’s Future Autonomy is at Stake, Says Expert.” The stage was set for a showdown between Regina Ip and John Kamm at the Bills Committee meeting on June 17.

Debate in Legco

I showed up at the Legco Building on June 17 at the appointed hour. I took my seat in the gallery above the ornate chamber, looking down on the legislators. Bob Allcock came up to where I was sitting and gave me a handwritten note. An amendment to the bill would be introduced changing the proscription mechanism from “certificate” to “open proclamation.”

The first order of business at the meeting was an attempt by Democratic legislators to rescind the June 14 decision to close debate. All their motions were voted down. Attention then turned to my objection to the bill as presented at the Hong Kong University conference.

Regina Ip tabled the motion to amend the bill by substituting “certificate” with “open proclamation.” This move was met with derision by the Democratic camp. One legislator remarked that after saying debate could not be reopened the government had in fact done just that. Legislators Emily Lau and Margaret Ng, stalwart campaigners for human rights and democracy, claimed that the amendment didn’t change a thing. What was meant by “open proclamation?” Could a newspaper advertisement placed by a local government be considered an “open proclamation?” The government had muddied the waters.

Finally, Lee Cheukyan took the floor. “Secretary for Security, you have said that the bill was subjected to scores of public consultations and 80 hours of debate by Legco. Yet, a foreigner comes to town who has never read the bill, examines it for less than an hour and finds a fatal flaw. What do you have to say to John Kamm?” Pointing at me, he said “Look at John Kamm sitting in the gallery. He is laughing at you!”

This proved too much for Regina Ip. “I am sick and tired of hearing from so-called foreign experts on Chinese law. Sick and tired!” she exclaimed in a high-pitched and agitated voice.

At this point, the Chairman of the Committee meeting stepped in and suggested a brief recess to allow tempers to calm down. I left the gallery and went downstairs to find Martin Lee waiting for me. He ushered me into a room where there were several dozen journalists waiting to pepper me with questions. I made it clear that I was not satisfied with the amendment. The bill was still flawed.

At this point I took a gamble. “The Ministry of Foreign Affairs holds its weekly press conference on Thursday June 19. There are journalists in this room who work for wire services. Why don’t you ask the Foreign Ministry spokesman who is right, John Kamm or Regina Ip?”

In making this move I reckoned that Regina Ip knew as little about Chinese bureaucratic politics as she knew about Chinese law. She had studiously built relations with the Hong Kong Macau Affairs Office, and had largely ignored the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a bad move. In the event, journalists submitted my question at the press briefing on June 19. The spokesman declined to answer. On June 25, 2003, Regina Ip tendered her resignation as Secretary for Security, citing personal reasons. Later that year she entered Stanford University to study for a Master’s Degree.

As I was exiting the Legco conference room on June 17, two journalists from Apple Daily and Ming Pao stopped me at the door. “What do you think of what Regina Ip said about you?” they asked. I played dumb, “What was that?” “She said that she was sick and tired of hearing from so-called foreign experts on Chinese law. She called you a so-called foreign expert.” I quipped: “I thought she was talking about Bob Allcock.” The press loved it.

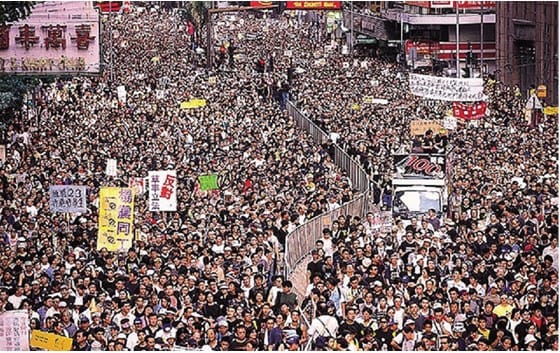

On July 1, 2003, hundreds of thousands of Hong Kong people took to the streets to protest Article 23. Government officials had predicted that only 30,000 people would participate in the march. The marchers wound through the streets and ended the march by passing by Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa’s office. They carried placards denouncing “Uncle Tung” and calling for his resignation.

With the desertion of James Tien, leader of the Liberal Party which had supported passage of the legislation, the National Security Bill’s fate was sealed. The government removed the bill from consideration by Legco. Citing health issues, Tung Chee-hwa resigned in March 2005. Mr. Tung remains in excellent health. He had apparently contracted a short-term political illness.

As for me, I returned to San Francisco, but my job was not complete. I penned an article that ran in both English and Chinese newspapers in Hong Kong outlining how the people of China would be hurt if the National Security Bill was passed by Legco and became law.

In the summer of 2003, a senior official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs came to San Francisco and we agreed to meet. He told me that “We know that the Hong Kong government has made many mistakes, but we don’t appreciate our friends pointing them out!” We had a good chuckle.

Fifteen years after the demise of the National Security Bill, China’s leaders, notably President Xi Jinping, are pushing for the SAR to enact Article 23 legislation, perhaps as early as the end of 2018. Opposition among the public to such legislation remains high – Regina Ip, the face of Article 23, received the lowest number of Election Committee votes for Chief Executive in 2017 – but due to changes in the make-up of Legco brought about by the ousting of several recently elected legislators, sanctioning speech and association under Article 23 could well be in Hong Kong’s future.