<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

Download & read this story as a PDF.

This “John Kamm Remembers” entry was originally published as part of the Dui Hua’s

September/October Digest (Issue 90), published October 19, 2022.

On February 11, 2022, I received an email from the Director of Alumni Services and Events at Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS). I was told that I had been nominated to receive the GSAS Centennial Medal, the highest honor bestowed on an alumnus of GSAS, given for significant contributions to society. First bestowed in 1989, the Centennial Medal had been given to around 140 GSAS alumni, including the essayist Susan Sontag and the political scientists Joseph Nye and Francis Fukuyama. I felt humbled and elated to join such a distinguished group of previous awardees. To me, this award was not only a personal honor, but a culmination of Harvard University’s enduring influence on my life and mission.

I enrolled in Harvard for my master’s degree at the age of 23. Though I had only spent two semesters there from 1974-75, they were among the happiest days of my life for both personal and academic reasons. In those two semesters, I learned to read classical Chinese by working through materials I gathered in Kam Tin in Hong Kong’s New Territories with Professor Yang Liensheng, wrote a paper on Chinese foreign trade corporations for Professor Dwight Perkins, and met my first Chinese counterrevolutionary in Professor Jerry Cohen’s seminar on Chinese law, laying the foundation of my human rights activism that began 15 years later.

The Role of Harvard’s Libraries in Prisoner Advocacy

When I was invited to attend the ceremony for the conferring of the GSAS Centennial Medal, I was informed that each of the honorands were allowed to invite a limited number of members of the Harvard community. I focused on inviting librarians who had helped me over the years.

As a human rights organization whose work is founded on its open-source research and advocacy for political and religious prisoners, Dui Hua’s researchers have managed to glean the names of hundreds of political and religious prisoners from the libraries in Harvard. Many of these prisoners were still serving sentences at the time their names were uncovered. Dui Hua placed their names on lists submitted to the Chinese government, after which several received clemency.

There are four libraries at Harvard holding materials with information on political crime in China: the H.C. Fung Library at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, the Harvard Law School Library, the Harvard Yenqing Library, and the Widener Library, the university’s largest library.

These libraries contain publications such as local gazettes, records, and yearbooks published by state security bureaus, public security bureaus, procuratorates, courts, and justice bureaus. They provide information on and insights into how China deals with political crimes through case examples, regulations, accounts of events (e.g., June 4, 1989), and statistics.

For a time, Dui Hua found useful materials in libraries in mainland China, but that is no longer possible as a result of Covid and political surveillance and harassment of our researchers. Such data is becoming harder to come by even in Hong Kong libraries, including Hong Kong University’s Fung Ping Shan Library and the Universities Services Centre at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. In the years after Dui Hua’s founding in 1999, most of the names were found by the foundation’s researchers, including me, at these two libraries. However, as China has increasingly asserted its control over the former colony, especially in the runup to the imposition of the National Security Law in 2020, materials deemed “sensitive” have been removed from the libraries, and no new ones have been ordered. The collections have been “harmonized.”

The libraries at Harvard are today one of the biggest repositories of names used by Dui Hua in its research and advocacy work and have filled the void left by their Chinese counterparts, but even these libraries are finding it more difficult to acquire volumes on political crime in China.

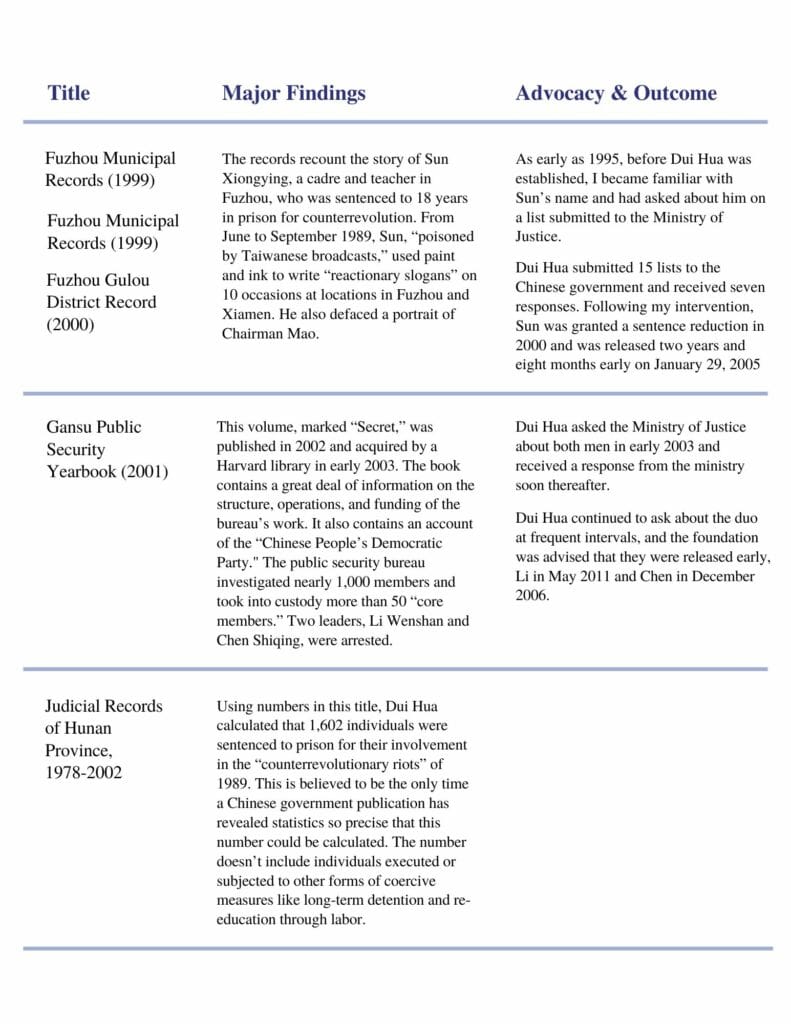

Some of our most notable findings from Harvard Libraries are listed at the end of this article.

Glorious May at Harvard

During the four days spent at Harvard in May 2022 as the awardee of the GSAS Centennial Medal, I attended several functions, including the medal ceremony on May 25. I also met with professors, including Professor Tian Xiaofei, who nominated me for the medal, Dwight Perkins – under whom I had studied in 1975 – and professors Mark Elliot, Michael Szonyi, and Bill Alford, before whose law school classes I had delivered remarks on several occasions. Of course, colleagues and I spent many fruitful hours in Harvard’s libraries.

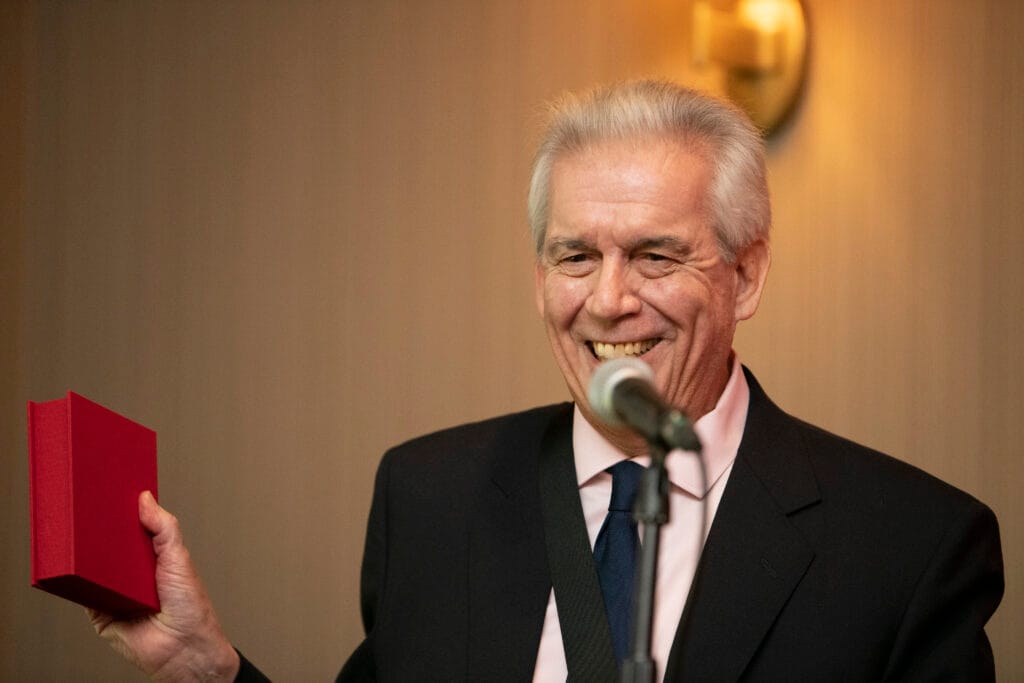

The highlight of the visit was the May 25 medal ceremony held at the Faculty Club. It was the first time I had stepped foot in the club. The time came to accept the Centennial Medal. I stepped to the podium where GSAS Dean and classicist Emma Dench, niece of famed British actress Judi Dench, read the citation and handed me the medal.

I was honored to stand alongside three other 2022 Centennial Medalists. They are:

- Neil Harris, PhD ’65, History, for his “pioneering work in shaping the field of cultural history”

- Vicki Sato, AB ’69, AM ’72, PhD ’72, Cellular and Developmental Biology, for her “visionary leadership and life-changing breakthroughs in the biopharmaceutical industry”

- Robert Zimmer, AM ’71, PhD ’75, Mathematics, for his “superlative leadership of [University of Chicago],” and his “principled advocacy for the core mission and values of higher education on the national and global stage”

More about the event:

My award acceptance speech

GSAS Centennial Medal Citation

Given Harvard GSAS’s pivotal role in shaping and aiding Dui Hua’s mission, the award is more than a personal honor. I am grateful to the GSAS, not only for myself but on behalf of the prisoner whose names were unknown but to God until they were found at Harvard — names embedded in truth, spoken to power.

Notable Findings from Harvard Libraries in May 2022

Baoshan Prefecture Public Security Records (2019)

- In late 2021, Dui Hua published Persecution of Unorthodox Religions in China, an exhaustive treatment of a rarely examined subject. Dui Hua identified 41 so-called cults operating in China in recent years. As many as 40 percent of “cult” prisoners in Dui Hua’s political prisoner database are women (women account for 8.5 percent of prisoners in China). Unorthodox religious groups often have extensive international links, and they are for the most part nonviolent.

- Baoshan Prefecture in Yunnan Province has a population of 2.5 million people with a substantial number of ethnic minorities. The Baoshan Prefecture Public Security Records identifies 10 unorthodox religious groups operating in the prefecture in recent years and gives the names of 79 adherents subjected to coercive measures, though few have been sentenced to prison. The four largest groups in terms of adherents subjected to coercive measures are Yi Guan Dao, Falun Gong, the Shouters, and Mentu Hui.

Records of Trials in Gansu Province (2018)

- It is not unusual to find statistics on crime in volumes found at Harvard University libraries. These statistics, when coupled with the set of Supreme People’s Court statistics, help fine-tune our knowledge of how political and religious crimes are handled in China.

Records of Trials in Gansu Province

- Contains tables of cases of endangering state security (ESS) and “using an evil cult to sabotage implementation of the law” (Article 300 of the Criminal Law) tried in Gansu from 1990 to 2015. We learned from the Supreme People’s Court statistics that the vast majority of splittism and inciting splittism cases are tried in provinces with large ethnic minority populations – Xinjiang, Tibet, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Gansu. From the Gansu volume we now know how many such trials took place in Gansu, which sports a large Tibetan population.

- In 1999, the Chinese government banned Falun Gong. The impact of this decision is evident in the table covering Article 300 trials in Gansu. From 1999 to 2015, 486 Article 300 trials took place in Gansu, with more than 40 percent taking place in the four-year period of 2012-2015. The Gansu table on trials of endangering state security uses the term “counterrevolution” to enumerate ESS trials for the entire period. In 1997 China removed the crime of counterrevolution from the criminal law and inserted the crime of endangering state security. The Gansu table confirms what has long been suspected: in the eyes of China’s judiciary, ESS is the same as counterrevolution, a crime defined by motive that is not based on “scientific forensics.”

Jiangsu Province Public Security Records (2010)

- It is widely believed that the Spring 1989 protests were confined to Beijing and a few other large cities. In fact, demonstrations and strikes took place in more than 300 cities and counties across China. The Jiangsu Province Public Security Records chronicles what took place in Nanchang, Jiangxi’s capital, from April 15 to June 25, 1989, including the dates and times of protests and transport disruptions and the names of organizations – chiefly autonomous student federations and independent worker’s unions – that were declared illegal and disbanded.

- Numbers of students and worker leaders and key members of the organizations are given, though no individual names are provided. Ten members of the Nanchang United Worker’s Union were “secretly arrested” but the term “secretly arrested” is not defined.

- The Nanchang account of the spring 1989 protests is but one of many found in Harvard libraries since Dui Hua began its research in 2000. Books published over the last few years rarely mention the events of 1989 as China’s leadership seeks to erase memory of the largest political protests to take place in the country since 1949.

Earlier Findings from Harvard Libraries & Their Contribution to Advocacy

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.