Embed from Getty Images

Chinese dissident and pro-democracy activist Xu Wenli prepares to speak to reporters before a press conference, 27 January 2003, in Washington DC, with his daughter Xu Jin (C) and Wife He Xintong (L). Photo by JOYCE NALTCHAYAN/AFP via Getty Images

It is not uncommon for China’s judicial authorities to exercise clemency on the occasion of holidays and festivals. Mark Swidan, Kai Li, and John Leung were released on Thanksgiving Day, 2024. American citizen Jude Shao was released two days before American Independence Day, 2008. Prisoners, political and religious as well as others, are often shown clemency in the run-up to China’s Spring Festival. Amnesties have been called to commemorate important dates.

For me, the most poignant holiday release was that of veteran activist Xu Wenli (徐文立).

On the way to the U.S.

At 1:15 AM on December 24, 2002, I received a phone call from an official who worked for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA). It was the early hours of Christmas Eve. Xu Wenli, leader of the China Democracy Party, had been released and was on his way to the United States.

I was asleep on the couch of my office in San Francisco. I had been expecting the call. The State Council Information Office (SCIO) was hoping to make the morning editions of American newspapers. This release, together with the release of the Tibetan filmmaker Ngawang Choephel and the Tibetan teacher Takna Jigme Sangpo earlier in 2002, was part of the charm offensive launched by Chinese President Jiang Zemin to cozy up to the United States in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington.

As soon as the conversation with the MFA official ended, I called two people: Xu Wenli’s daughter in the U.S., Xu Jin, and Mark Lambert at the American Embassy in Beijing. Mark was the human rights officer at the embassy. He would go on the play a leading role in shaping U.S. policy towards China in the Biden administration.

Xu Wenli served two terms in prison for his political activism. The first imprisonment took place between April 1981 and May 1993 (he was released on parole in late May). The second jailing took place between November 1998 and December 2002 (he was released on medical parole on Christmas Eve.)

Xu’s release in 1993 was widely covered by international media.

Xu, with Wei Jingsheng, were leaders of the Democracy Wall Movement that erupted in major Chinese cities in 1979. Both men wound up serving more than 10 years in prison beginning in 1981. Xu in a Beijing prison, Wei in a specialized facility in neighboring Hebei Province. An account of Xu’s first imprisonment, written by me, can be found in “Prisoner 001.”

Xu and Wei were detained around the same time and sentenced for the same crime, counterrevolution. After their release, Wei went to the U.S., where he lives today, while Xu elected to stay in China.

The two men are very different. Wei is brash. He enjoys the limelight and especially likes the attention he gets from testifying at congressional hearings. Wei had excellent relations with Beijing-based foreign journalists in the early 1990s.

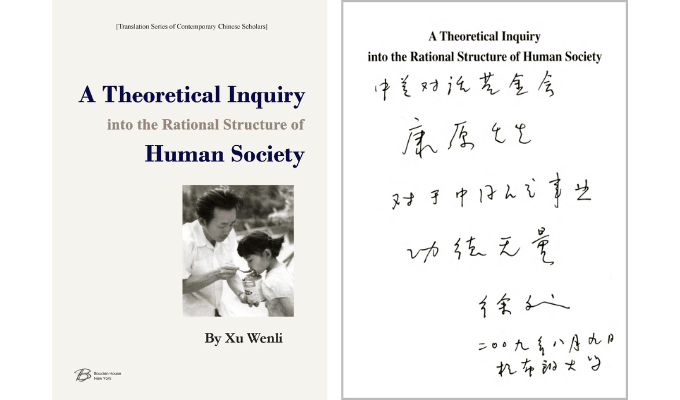

Xu, by contrast, is quiet and reserved. He is a serious intellectual who has authored books on political science. He has never testified before Congress. Reflecting his intellect and speaking abilities, Xu was invited to teach at Brown University upon his arrival in the U.S. after his second imprisonment ended in 2002.

Second Imprisonment

In 1997, China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) amended the country’s Criminal Law and Criminal Procedure Law. The crime of counterrevolution was removed from the Criminal Law and the crimes of endangering state security and using a cult to undermine implementation of the law were added. Judicial reform seemed to be underway.

In June 1998, U.S. President Bill Clinton traveled to China, visiting Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. President Clinton and President Jiang held a joint news conference in which Clinton told Jiang he should meet the Dalai Lama. He also referenced the removal of counterrevolution from the Criminal Law and recommended releasing those who were in prison serving sentences for this crime, a proposal I had put forward to the White House before his departure for China. The joint press conference received a great deal of attention from the Western media.

Unfortunately for the reform movement, conservative members of China’s Politburo as well as senior military leaders paid close attention to what was said by the two leaders and were furious that Jiang didn’t push back, especially on the suggestion that Jiang would enjoy the company of the Dalai Lama.

Right after Clinton left China to attend to domestic problems (notably the Monica Lewinsky scandal), a Hangzhou activist by the name of Wang Youcai tried to establish the Zhejiang Branch of the China Democracy Party (CDP), His application got nowhere, but Beijing soon caught wind of what was going on. Jiang Zemin ordered the authorities to nip the nascent democracy movement in the bud. Wang Youcai was detained on October 8, 1998, and subsequently sentenced to 11 years in prison for the crime of subversion.

Three days before Wang was detained, China signed the United Nations Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The convention establishes the right to form political parties. (Although it signed the ICCPR in 1998, China’s NPC has yet to ratify it.)

On November 9, 1998, Xu Wenli and fellow activists, including He Depu (何德普), Gao Hongming (高洪明), Lü Shizhun (刘世遵), and Zha Jianguo (查建国), announced the establishment of the CDP Beijing-Tianjin Branch. Three weeks later, on November 30, Xu was detained. Around the same time, the fellow activists who joined him in the attempt to register the party were also detained. Xu was subsequently sentenced to 13 years in prison and three years deprivation of political rights. He was sent to Yanqing Prison to serve his sentence.

As he did during Xu’s first term in prison, Hong Kong-based human rights champion Robin Munro encouraged me to seek clemency for Xu. Munro, who passed away in Taiwan in 2021, was Human Rights Watch’s China researcher in Hong Kong. He had gotten to know Xu in Beijing well before his arrest in 1981. They became fast friends.

By the time I took up Xu’s case, for the second time, in 1998, I had been intervening on behalf of Chinese political and religious prisoners for more than eight years. I had developed a modus operandi of interactions and dialogues used to work with different parties in an intervention. In the coming years I was to deploy this M.O. in hundreds of cases.

Interactions with Family Members

Gaining the trust of the prisoner’s family is vital. The trust I gained during Xu’s first imprisonment carried over to the second imprisonment.

Especially valuable was the help I received from Xu’s daughter, Xu Jin, who had relocated to the U.S. In July 2001, Xu Jin sent me the results of her father’s medical tests. The information informed the application for Xu Wenli’s medical parole, which was eventually granted.

Dialogue with the Chinese Government

What distinguishes my work—and, after 1999, the work of Dui Hua—is the ability to engage the Chinese government in a dialogue on human rights and the treatment of prisoners. This work entails both face-to-face meetings and submission of lists to Chinese government ministries. Lists are submitted directly and through governments with whom we work. During the term of Xu’s second imprisonment, we submitted eight lists and received seven responses from the Chinese government.

In reviewing notes from my meetings with my Chinese interlocutors, I am struck by the references to Xu’s bad attitude and, resulting from that, the unlikeliness of his early release from prison. They denied that Xu was in poor health. “He’s quite healthy,” they claimed.

I usually was the one to seek in-person meetings, but on at least one occasion, an official unexpectedly asked to see me. On the evening of November 1, 2002, a senior official came to my hotel in Beijing. He was dressed casually and wanted to discuss real estate opportunities. We eventually got around to discussing Xu Wenli. He advised me that Xu’s release, already agreed to internally, had hit a roadblock, mostly for domestic political reasons having to do with the selection of Hu Jintao as Secretary General of the Chinese Communist Party. Some conservatives were pressing Hu not to release any more political prisoners. Their opposition was eventually overcome.

Dialogue with the U.S. Government

The administration of George W. Bush, who took office in January 2001, actively worked to secure the release of two activists: Uyghur entrepreneur and humanitarian Rebiya Kadeer and Xu Wenli. President Bush relied on two American officials, his old friend Ambassador to China Clark “Sandy” Randt, and Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Rights and Labor Lorne Craner. Both men asked for my assistance.

Dialogues with Other Governments

In an effort to ward off sanctions, Beijing began holding human rights dialogues with other governments in the 1990s. In addition to the U.S., China was discussing human rights with seven other countries at the time of Xu Wenli’s and Wang Youcai’s arrest in 1998. Dui Hua assisted several of these by composing prisoner lists and proposing topics for discussion. Xu figured prominently in both.

Interactions with NGOs

On the whole, my interactions on the Xu Wenli case with the human rights and dissident communities were good. By far the most helpful was Robin Munro. He headed the Human Rights Watch office in Hong Kong from 1990 to 1999. Our offices were within a hundred yards of each other, and we met frequently. He introduced me to the case, and pressed me to intervene with my Chinese interlocutors.

While Munro supported my work, our collaboration on the Xu case and many others outraged both the human rights community and the business community, members of which toyed with the idea of denouncing me. As the saying goes,”If both sides condemn you, you must be doing something right!”

Cooperation with Amnesty International was enhanced by my strong relationship with the Norwegian government. Amnesty’s Norwegian branch chronicled Xu’s case and my role in assisting him during his first and second imprisonments in an account published in 2003.

Media Coverage

Dui Hua announced Xu’s Christmas Eve release in a press statement issued immediately after calling Xu Jin and the American Embassy in Beijing. Media coverage was extensive. China’s actions against the CDP and its leaders, Xu Wenli and Wang Youcai, had garnered much media attention, so journalists had plenty of material to work with.

Aftermath

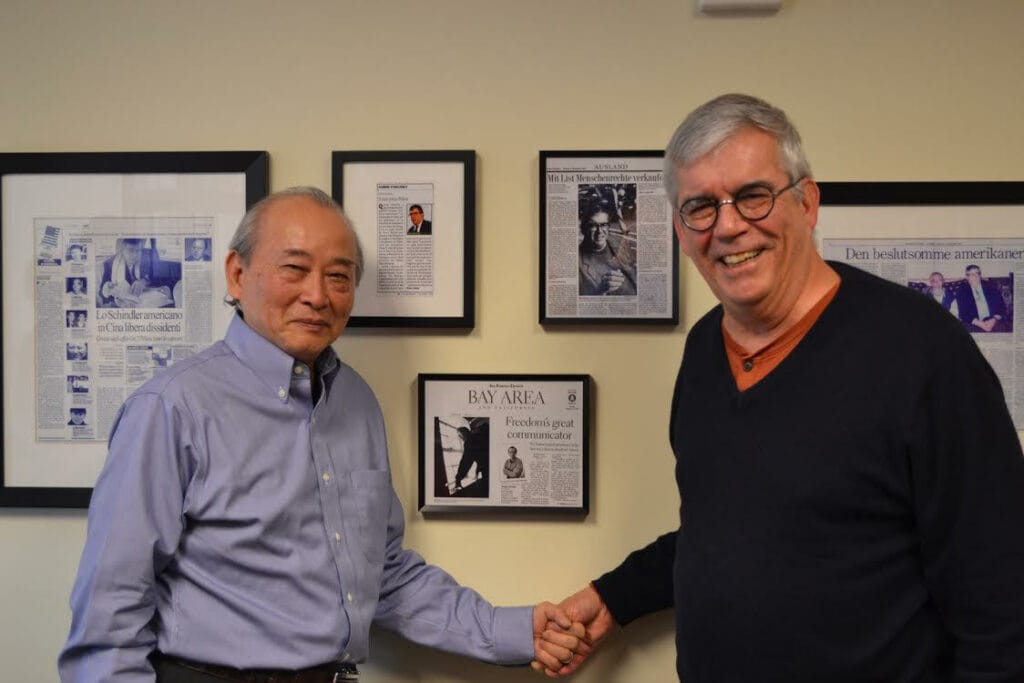

After his release, Xu came to San Francisco to see me at my office. He visited three times. We posed for photographs and enjoyed lunches. Xu was accompanied, on occasion, by his wife, He Xintong, and former political prisoners including Wang Xizhe and Wang Dan.

Now 82 years old, Xu remains active. He lives with his family in Providence, Rhode Island and is a senior research fellow emeritus at Brown University. In January 2024, he donated his papers to Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. His legacy as a champion of human rights and democracy is secure.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.