<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

With the opening of China in 1972, a young John Kamm embarked on his China venture, starting in Macau and then Hong Kong. In 1976, he began attending trade fairs in mainland China in the waning days of the Cultural Revolution. A journalist and trade promoter during a period of political upheaval, Kamm’s work took him throughout the largest cities and surrounding countryside, including Guangzhou and the Pearl River Delta. Kamm saw aspects of Chinese life largely unknown to those living in the West. This instalment of John Kamm Remembers details some of Kamm’s experiences during this period. In March, we will release a companion piece, “Nothing Starts Without a Sale: Learning to Sell in Cultural Revolution China,” focusing on the bi-annual Chinese Export Commodities Fair held in Guangzhou.

I

moved to Hong Kong (then a British crown colony) in 1972 and started working as an assistant editor of Asian Business & Industry, a business magazine published by Far East Trade Press, in the summer of 1975. Though I mainly wrote about business in China, up till then I had not set foot in the Chinese mainland, as it was closed to most foreigners.

The chance to realize my dream of visiting China finally came by in 1976 when, as a freshly minted representative of the National Council for US-China Trade, I was asked to attend trade fairs in China, starting with so-called mini-fairs. Reforms introduced in 1975, which permitted practices like sewing foreign labels in Chinese garments, were reversed in early 1976, casualties of the Cultural Revolution’s dictates to refrain from “worshipping things foreign.”

Back then, trade fairs provided the only opportunities for foreign businesses to meet their Chinese suppliers face-to-face, so invitations were highly sought after. One of the largest trade fairs was the Canton Trade Fair in Guangzhou. It was a month-long affair that was held twice a year, from April to May and October to November, respectively.

Memories of the Dongfang Hotel

During the Canton Trade Fair, Europeans and Americans stayed at a hotel designated for foreigners (Japanese and Hong Kong businesspeople had their own designated hotels) called the Dongfang Hotel. The US Consulate, established in 1979, was located on the 11th floor of the hotel’s new wing. The place was a hotbed for networking and exchanging insights into China, and I still remember it fondly as the home base for my first forays into China during the waning days of the Cultural Revolution.*

Liaison offices, manned by foreign affairs and public security officers, were established in each hotel. This is where one registered for the fair and was given a red ribbon which one wore to enter the vast trade fair complex.

The Dongfang had a large dining hall open for three meals a day. At the 1977 autumn fair a hamburger stand was opened on the ground floor. The management of the hotel took other steps to make it more livable for foreigners. Not all were successful. The management purchased a large quantity of imported rodenticide which they deployed liberally throughout the hotel. While many rats were killed, others were routed from their lairs and were seen scurrying around the halls. One fairgoer spoke of rats as big as cats. Another was rudely awakened from his sleep by a rat that had fallen into the fan in his room. Yet another thought she had trapped a rat in a desk. The rat gnawed its way out of the desk and found a place to live elsewhere in the room.

Unlike other Asian cities visited by businesspeople, there were no night clubs or massage parlors in Guangzhou. There was a bar on the eighth floor of the Dongfang Hotel, the storied “Top of the Fang,” and dozens of restaurants in the city where businesspeople could rent rooms (mingling with locals was not encouraged) for lavish banquets.

To compensate for the loss of Japanese life in the 1976 Tangshan quake, China purchased Japanese cars and air conditioners. The latter were placed in the courtyard of the Dongfang, exposed to the elements. When a small number were eventually turned on, the fuses were blown, shutting off power at the Dongfang. The Japanese cars were stripped of everything that could be used, including tires. They wound up on cinder blocks sitting forlornly in the lot in front of the Dongfang.

Excursions & Sports Around Guangzhou

The liaison office at Dongfang Hotel organized visits to sites inside and outside Guangzhou. One could join tours to visit communes, factories, and tourist locations like the Birds Paradise in Xinhui District. I remember visiting a hospital to observe operations under acupuncture anesthesia. The patient, on cue, would sit up and wave to the foreign guests. Not a few members of the audience fainted. Fireworks manufacturing was booming in Dongguan County, as fireworks factories in Guangdong started displacing the firework factories in Macau starting in the late 1960s.

Though I had studied Mandarin when I was at Princeton, while living in Hong Kong, I ditched it in favor of Cantonese, a very different language, akin to the difference between Dutch and English. Chinese officials who came to Guangzhou from Beijing could neither speak nor understand Cantonese (the common dialect used in Guangdong Province). When they joined tours of communes, I often wound up interpreting for them.

Table tennis tables were set up in the hotels where foreigners stayed, as well as the occasional pool table. There were clay tennis courts on Shamian Island where an enterprising American businessman tried to organize a tennis tournament (“the Canton Cup”) at the autumn fair. Unfortunately, the Chinese Tennis Association, which we did not know existed, stepped in, and ordered a halt to the tournament. That did not stop several of us from playing a few sets at the appointed date and time. The businessman, who represented a sporting goods firm, distributed cans of tennis balls, tennis hats, and other paraphernalia.

During the autumn fair, a football game was organized between foreigners and Chinese players on a pitch at Zhongshan University. The Chinese team invariably won, but, true to the motto “Friendship first, competition second,” the Chinese team let the foreigners keep it close by scoring one or two goals.

Streets of Guangzhou

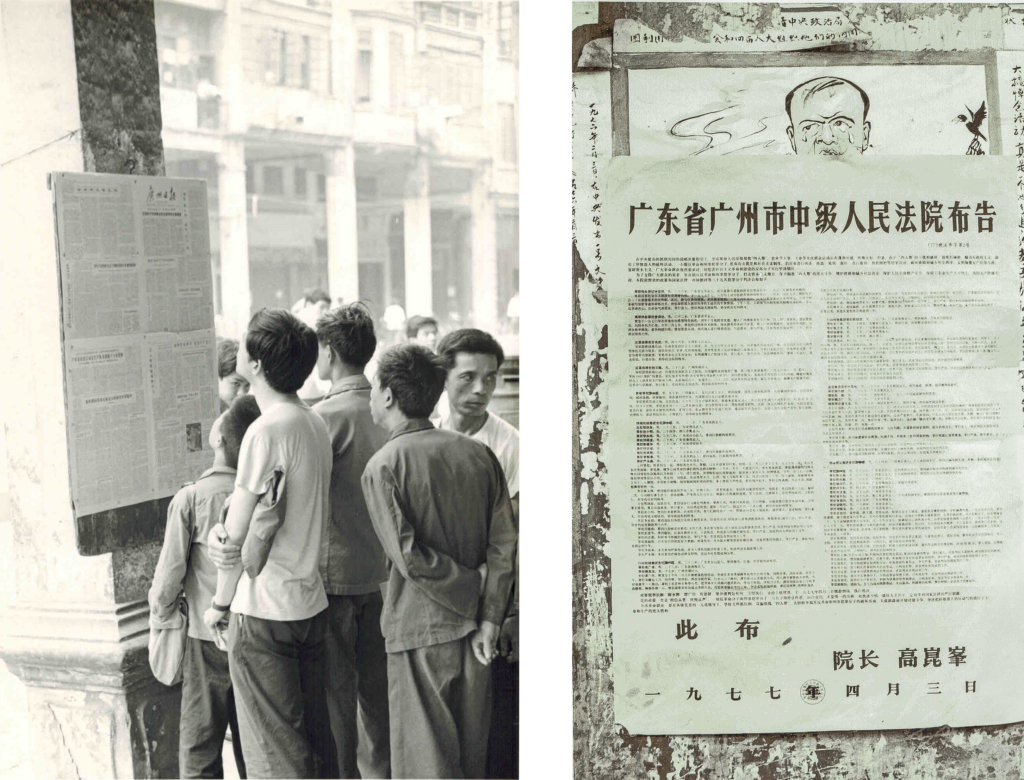

There was plenty of time to wander the streets of Guangzhou. Occasionally, I would see a court notice of executions of convicted criminals, including counterrevolutionaries, posted on walls in the city. Such notices, common during the Cultural Revolution, are no longer seen today.

In 1983, I learned of the executions of two Hong Kong young men who had hung a large banner with counterrevolutionary slogans outside their hotel room. They went outside the hotel and took photographs after which they headed to the train station to return to Hong Kong. There they were taken into custody, after which they were tried, convicted, and executed. The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) in Beijing approved the execution. In those days, the only executions that needed to get the approval of the SPC were those for counterrevolution. (Now all executions need to be approved by the SPC).

The execution of these two men for hanging a poster out of their window prompted outrage among the people of Hong Kong. It marked the last time that Hong Kong people were executed for political crimes. Executions for other crimes, notably drug offenses, have continued to the present day.

I often wandered into stores to see what was on offer. The only foreign consumer goods available for purchase in those days were Swiss watches, Albanian cigarettes, North Korean brandy, and books by leaders of friendly countries like Enver Hoxha of Albania. Japanese televisions began to be available for sale in 1977.

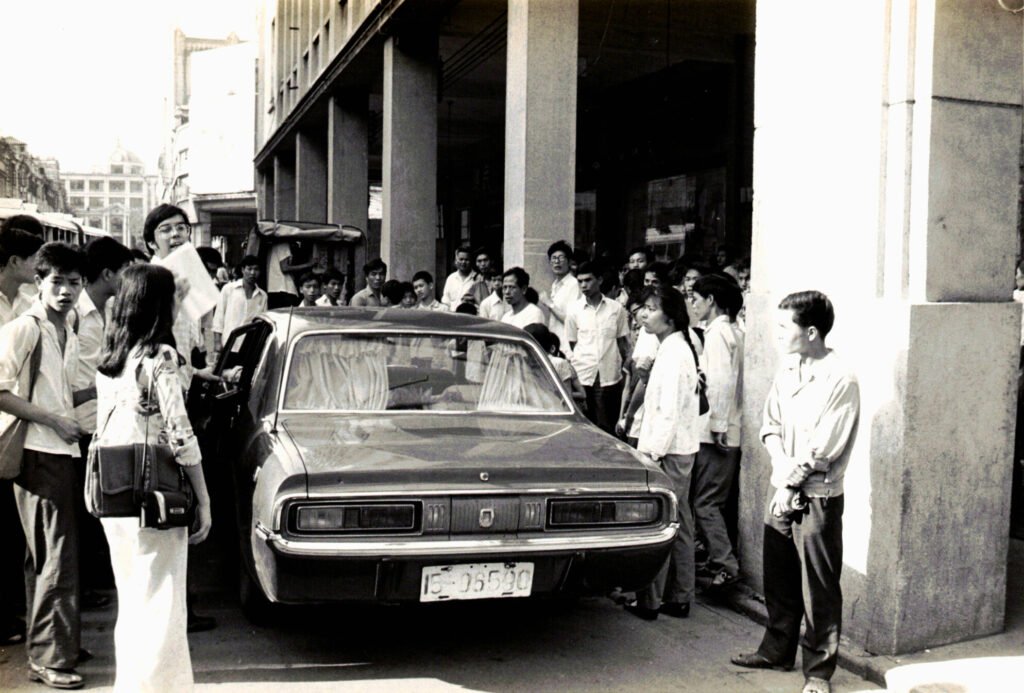

On one occasion, I befriended a taxi driver outside the Dongfang. He asked me to buy a Chinese watch (which were rationed for locals) at a local department store with renminbi he gave me. I did so and handed it over. Later, I saw him again and went into the back seat of his car. He pretended not to recognize me. Such was the fear among locals of fraternizing with foreigners.

The public security bureau did their best to make sure disturbances like fights did not take place, but they couldn’t stop all deviant behavior. On one occasion, I witnessed a fight between youth hurling rotten vegetables at the crews of sampans tied up on the shoreline of Shamian Island. On an arranged visit to Dongguan County, I witnessed a fight between an individual and a group of gangsters. On a walk near the trade fair building with a female colleague a fast-moving bicyclist tried to harass her physically and sped away.

Worshiping was another deviant behavior discouraged by the authorities, but it was known to take place in private dwellings. Churches, including the massive Sacred Heart Catholic Cathedral, were boarded up. Priests, including Father Tan Tiande, who suffered greatly during the Cultural Revolution, could not be visited. It took until the early 1990s for visits to be allowed, under the watchful eye of Religious Affairs officials.

The North Korean Trade Office on Shamian Island

Shamian Island is a sandbar located in the southern part of Guangzhou. Prior to 1949, it was the site of the British and French concessions. In the early 1950s, most foreigners left Guangzhou, leaving behind stately Western edifices and a couple of churches, one Anglican and one Catholic. Eventually two new foreign offices opened on the island: a Polish consulate was set up to service crews of the Sino-Polish shipping company and a North Korean trade office was established to conduct business in Macau and Hong Kong.

During the US presidential election campaign of 1976, candidate Jimmy Carter pledged to remove US troops from South Korea. This was a popular position among the North Koreans who worked at the trade office on Shamian. North Korean trade representatives had little opportunity to meet foreign businesspeople, but they were invited to attend receptions put on by foreign governments, notably the Swiss government. During the autumn 1976 trade fair, I met several North Korean officials who were very friendly, unlike the way I was greeted at the spring 1976 trade fair. On that occasion they scowled, refused to shake my hand, and turned their backs to me.

At the autumn 1976 fair I was invited to visit the North Korean trade office on Shamian. Before accepting, I went to the liaison office and asked if there were objections to my going to the trade office. The response I received was surprising. I was told not to visit the North Koreans. “You are here at our invitation, not theirs. Stay away from them.” This was an early indication that relations between Beijing and Pyongyang were not as close as many in the West thought they were.

Recollections of the Cultural Revolution

My wife and I became good friends of the Polish Consul General and his wife. We frequently visited the consulate on Shamian Island and invited them to our office at the Dongfang Hotel where small parties took place.

Polish officials lived in Guangzhou throughout the Cultural Revolution. Sitting on the balcony of the consulate they witnessed fierce shelling between rebel factions on Baiyun Mountain and the army on the south bank of the Pearl River. As Catholics, they attended mass at Our Lady of Lourdes Chapel on Shamian for as long as they could. First, the Red Guards ordered the congregants to stop singing, and then harsh measures were adopted against the Chinese priests, who were beaten and executed, strung up on Renmin Road lamp posts in downtown Guangzhou.

A Hong Kong businessman who visited our office recalled: “I lived in Guangzhou during the 1966-1968 period. There was a breakdown of social order. One stayed in one’s own neighborhood and was careful not to enter other neighborhoods as a stranger. On one occasion, a stranger entered a neighborhood near where I lived. The residents beat pans and drums and set upon him. He died a terrible death.”

Before visiting China in the mid-1970s, I fancied myself an admirer of Chairman Mao and the sayings in his “Little Red Book.” What I saw and heard back then changed me. I lost my innocence and adopted a skeptical view. I was no longer a “panda hugger,” a term applied to those who hold that China can do no harm.

*Note: While there is general agreement that the Cultural Revolution began in 1966, there is no general agreement on when it ended. A leading authority on the Cultural Revolution in the West, Professor Fred Teiwes, has laid out four possible dates in the 1968-1978 period. Professor Teiwes and other experts date the end of the Cultural Revolution to 1966-1968, when the worst excesses took place. For this episode of John Kamm Remembers, I take the end of 1977, when Deng Xiaoping was rehabilitated, as the culmination of the Cultural Revolution.