<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

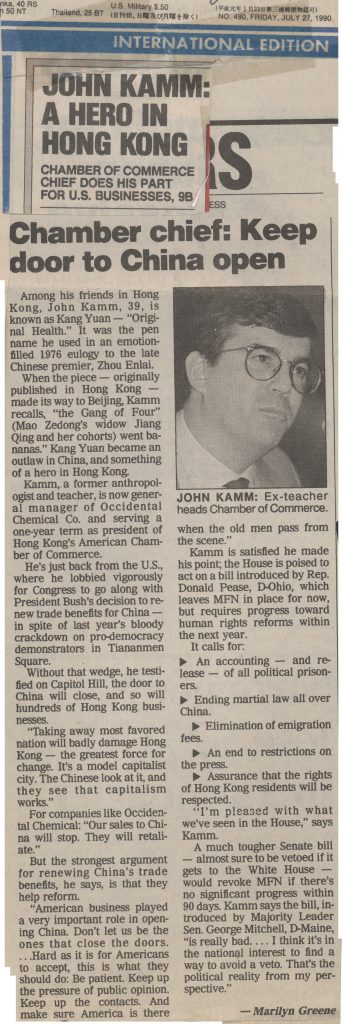

On January 1, 1990, I began my one-year term as president of the American Chamber of Commerce (Amcham) in Hong Kong. As recounted elsewhere, there was opposition from large corporate members to my becoming president. Many of them resented my having pushed through a resolution condemning the June 4, 1989 killings. A former president of Amcham claimed, with no evidence, that the Hong Kong government opposed the prospect of my becoming Amcham president and would refuse to work with me.

1990 would prove to be an eventful year marked by my testifying three times to Congress on China’s Most Favored Nation (MFN) trade status – before subcommittees of the House Foreign Affairs Committee (May 16, 1990), the Trade Subcommittee of the House Ways and Means Committee (June 19, 1990), and the Senate Finance Committee (June 20, 1990). My argument – that withdrawing MFN from China would cause massive collateral damage to Hong Kong – was cited by President George H. W. Bush in his May 24, 1990 statement renewing China’s MFN.

The MFN decision is thought to have been the first time in American history where the then-colony had played a role in a major foreign policy decision.

The chamber also successfully lobbied the Bush administration to issue an executive order protecting visas for Chinese students, and it urged the normalization of relations with Vietnam. In September 1990, I led the first American delegation to Mongolia after that country’s democratic revolution.

Internally, I oversaw the raising of membership dues by a large percentage; the chamber lost very few members. This hike in dues resulted in the chamber banking a significant sum, which enabled it to purchase its own premises in the Bank of America Building, a property it occupies to the present day. I was proud to have welcomed the first businesswoman onto the chamber’s executive council, a long overdue step.

Towards a Hong Kong Policy

On November 16, 1990, as my term of office was about to expire, I traveled to New York. I gave a speech at the Harvard Club in which I called for legislation to protect Hong Kong’s special status under United States law, an initiative that contributed to the enactment of the Hong Kong Policy Act in 1992. The speech, titled “Towards a Hong Kong Policy,” was hosted by the National Committee on US-China Relations.” It was attended by more than 60 local and state officials, journalists, businesspeople and traders, and lawyers, including President John F. Kennedy’s speech writer Ted Sorenson and the celebrated China expert Jerome A. Cohen. It didn’t take long for my speech to find its way to Washington D.C.

I started my remarks by noting that little thought had been given to fashioning a national policy to protect and enhance America’s substantial interests in Hong Kong, and then went on to list what those substantial interests were: America’s 14th largest trading partner, home for more than 160 American-owned factories worth $1.4 billion in investment, shared culture and values, and an American population of more than 20,000 citizens. I estimated that 200,000 Hong Kong people would emigrate to the United States over the next ten years.

I declared that “The United States has a special responsibility with respect to the Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong. . .Ours was the first government to recognize the declaration, later leading the vote in the United Nations on registering the Joint Declaration as an international treaty.” I stressed that the United States has a moral responsibility to be true to our own ideology of free enterprise and respect for human rights. “If America is a shining city on a hill, nowhere is the glow reflected more brilliantly than Hong Kong.”

I questioned how well the Joint Declaration was being honored, and I gave a somewhat tepid response. It was being honored “in the main.” I pointed out that there had been a series of disagreements between the United Kingdom and China on such matters as the pace of democratization, the British Nationality Act, the Port and Airport Development Strategy (which called for the building of a new airport), and cross border controls. “Fortunately, neither side has accused the other of breaking the Joint Declaration.” How times have changed!

I concluded my remarks by suggesting initiatives for the American government and institutions to preserve and protect Hong Kong:

- Washington should keep Hong Kong interests in mind when considering policies towards China. Institutions, whether academic, professional, religious or public-service oriented, should strengthen ties with counterparts in Hong Kong.

- Government should examine Hong Kong’s Basic Law and make comments and suggestions on areas where it can be improved. “I have been particularly vocal on the article relating to subversion and state secrets (Article 23). China’s insistence that Hong Kong pass laws against possession of undefined state secrets represents a serious threat to the free flow of information crucial to Hong Kong’s commercial vitality.”

- The United States should seek to negotiate directly with the Hong Kong government on trade, investment, and taxation treaties necessary for the further development of US-Hong Kong economic relations. The trade treaty should cover separate tariff treatment, trade quotas, bilateral dispute settlement, protection against expropriation, and the establishment of trade offices on each other’s territory.

- Washington should seek treaties with the sovereign powers (China and the United Kingdom) guaranteeing consular access, port visits by military vessels, and reciprocal air traffic rights.

- The United States should support Hong Kong’s full participation in international trade and financial organizations. “We need to work harder to insure Hong Kong’s admission to the Asia Pacific Economic Council.” I suggested that Congress enact legislation to ensure that Hong Kong continues to have access to American companies offering high technology goods and services.

- “Congress should reinforce legislation on Hong Kong’s separate immigration status after 1997.”

- I recommended that the executive branch pressure the Hong Kong government to demonstrate greater commitment to the internationalization of Hong Kong. I cited the “pressing need to involve foreign nationals in as many areas of public life as possible.” I suggested that the Hong Kong civil service be internationalized.

I wound up my speech with these words: “Inasmuch as legislative authority and direction will be required for granting Hong Kong separate trade and immigration benefits, Congress should, at an early date, enact a Hong Kong Relations Act.”

On September 20, 1991, Senator Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) – whom I had met when he visited Hong Kong in 1990 – introduced the Hong Kong Policy Act. The legislation included most of my recommendations. It was eventually signed into law by President George H. W. Bush on October 5, 1992. It was amended by the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act on November 27, 2019.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.