EVENTS

Xinjiang Vote Fails at UN HRC

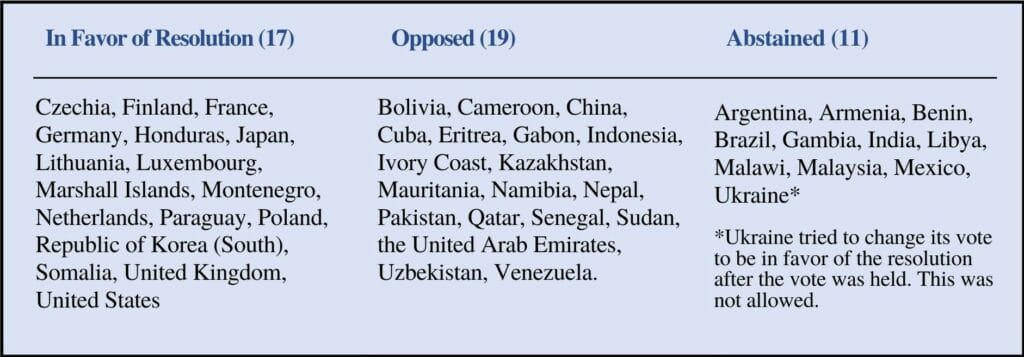

On October 6, 2022, the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) voted against holding a debate on China’s human rights violations in Xinjiang, which would have been held at the first HRC session in 2023. The procedural motion failed with 17 countries supporting and 19 opposing. Eleven countries serving on the 47-member body abstained.

The vote came at the first HRC session since the release of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)’s report that said that the Chinese government is likely committing crimes against humanity against the Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities. The vote was a culmination of years of efforts to hold China to account for its actions in Xinjiang, including dueling joint statements, the first UN visit to China since 2005, and intense lobbying over the report, which High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet published 12 minutes before her term ended. The report made an impact, but, going into the session, many wondered if it would be enough.

Potemkin Visit

Despite being completed in late 2021, the OHCHR’s report on Xinjiang was delayed repeatedly. The announcement that Bachelet would visit China in May 2022 shifted focus and resulted in a further delay of issuing the report. Activists warned of a “Potemkin visit,” by which China would co-opt the authority of the UN to whitewash its policies. Prior to the visit, China ratified two International Labor Organization (ILO) treaties on forced labor.

Bachelet visited China from May 23-28. Both Bachelet and the Chinese government framed the visit as a success, but activists and the international community criticized it harshly as a dent to the OHCHR’s integrity. More than 200 human rights groups called for Bachelet’s resignation. Dui Hua previously listed some of the failings of Bachelet’s visit, noting her limited time in the XUAR (48 hours total) and her parroting of Chinese government narratives. In her press conference, Bachelet said that detainees’ families “were heard” but later acknowledged that she failed to meet with detained Uyghurs or their families. The OHCHR requested “unfettered, meaningful, credible access,” but Bachelet’s team confirmed that Chinese officials accompanied her at almost every meeting.

At the opening of the 50th session of the HRC this past June, Bachelet announced that she would not seek a second term, saying that she wanted to spend time with family, and that she would release the report before stepping down.

A Long-Delayed Report

Heavy lobbying to bury the report continued. China reportedly sent the OHCHR a letter signed by 40 nations urging the council not to release the report. Shortly before midnight on August 31, the report was released.

The report found that “serious human rights violations” were committed in Xinjiang that are “characterized by a discriminatory component” that resulted in the “large-scale arbitrary deprivation of liberty” of Uyghur and ethnic minority residents. It concluded that China’s actions may constitute international crimes including “crimes against humanity” due to the “extent of arbitrary and discriminatory detention” conducted “pursuant to law and policy” and occurring amidst “restrictions and deprivation” of fundamental rights; more so, the report emphasizes that “conditions remain in place for serious violations to continue and recur.”

The report found credible proof of human rights violations including arbitrary detention, torture, ill treatment, non-consensual medical treatment, and sexual and gender-based violence against those detained or imprisoned. Rights violations faced by Uyghurs who are currently detained include prohibitions on cultural expression, extensive surveillance, non-consensual biometric data collection, forced labor conditions, and forced birth control and possible forced sterilizations.

The report notably did not use the term “genocide,” a fact that was criticized by Uyghur activists and Bachelet’s predecessor as high commissioner Zeid Ra’ad Al-Hussein.

The Vote

Activists and the US-led bloc sought to leverage the momentum of the report and the fallout from Bachelet’s visit into a vote at the HRC. The vote was to approve a procedural motion to hold a debate in 2023 on China’s policies in the XUAR at the next HRC session. The 47 members of the HRC voted on October 6.

As with many of the joint statements and special events at the UN over the past few years, this vote was decided after intense lobbying. The resolution’s narrow defeat by 2-3 votes was a source of suspense in the chamber, even as some experts predicted that it would fall short of the vote. Indonesia, Malaysia, and Qatar were reportedly pressured by China to vote no; only Malaysia elected to abstain. Representatives from both Indonesia and Qatar later said that their votes against the motion were because the discussion “will not yield meaningful progress” unless China consented to a vote. China ties aid to how a country votes on resolutions and motions at the HRC. The United States and its allies don’t.

Prior to the establishment of the HRC in 2005, individual countries could sponsor so-called country resolutions at the Commission on Human Rights. Twelve such resolutions were introduced over many years. China defeated all of them with “no action motions.” China famously threatened Denmark for introducing a China resolution, promising to squash the Nordic country like a sparrow.

The United States refused to link aid and assistance to how a country voted on these actions at the Commission on Human Rights. China, on the other hand, made aid and assistance contingent on how a country voted. Geraldine Ferraro, the US representative on the commission, once quipped that many countries in Africa had football stadiums built with Chinese aid, thanks to the US “China resolutions” introduced at the commission.

The US policy of not tying aid to how a country votes at the HRC explains why Ukraine, which receives billions of dollars from the United States, felt free to abstain on the procedural motion to hold a debate at HRC 52. (The day after the vote, Ukraine tried to change its vote from abstain to yes but the president of the Council, Argentina, refused to allow it.) Ukraine clearly felt that it would gain leverage with China that Beijing could use to deter Russian aggression against the country. It should also be noted that Ukraine is a part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. As Politico reported, 20 of the countries that voted no or abstained, like Ukraine, are part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

The ongoing support of Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) member countries for China’s policies toward ethnic Muslims continues to frustrate activists, reflecting the extent to which China’s lobbying and messaging successfully deflect criticisms. Of the 47 countries on the HRC, Somalia was the only OIC member and the only African country to support the motion.

This UN session was problematic as the Western bloc of nations lobbied for votes on two fronts: for the HRC motion on China and for another resolution at the HRC to appoint an independent expert on human rights abuses in Russia. The HRC motion on Xinjiang was thought to be the weakest possible form of rebuking China, only calling for a debate rather than a monitoring mission or a special rapporteur. Had the motion passed, it would have been the first time that China’s human rights record was addressed as a specific agenda item at the HRC.

The other lobbying effort appeared to pay off not only at the HRC but also at the General Assembly on October 12, when 143 of the 183 Assembly members voted to condemn Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian territory. Five countries including Russia voted no, the others being Belarus, Nicaragua, North Korea, and Syria. China, despite its “no limits” alliance with Russia, was one of 35 countries that abstained.

PUBLICATIONS ROUND UP

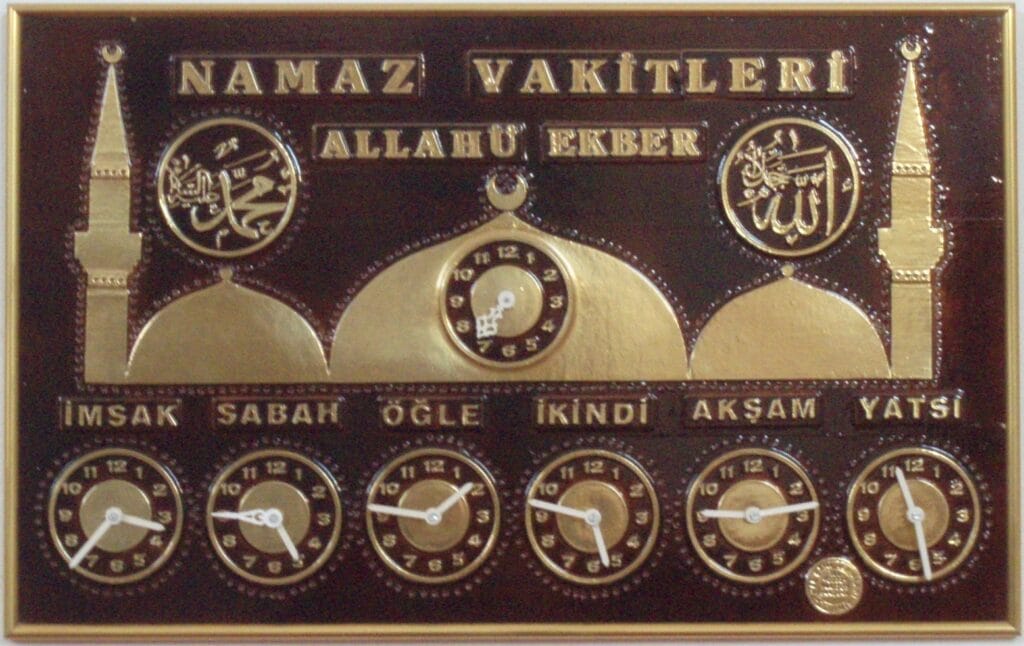

Featured: Human Rights Journal, Punishing Namaz Prayer in Prison, Part I: “Sabotaging Prison Supervision” (October 4, 2022) & Part II: “Illegal Religious Activity” (October 11, 2022)

Muslims around the world are obliged to perform five daily prayers at dawn, midday, afternoon, sunset, and night. The ritual, commonly known as salah, is often called namazi (CN: 乃玛孜) in China, a Persian transliteration of namāz. Within China’s carceral system, all forms of religious worship, including namāz, are forbidden. Prisoners who covertly perform namāz are at risk of receiving harsh punishment, with the most serious penalty being a sentence extension.

Read more here.

See Also: 2021 Annual Report

Dui Hua’s 2021 Annual Report recounts a year of achievements across a challenging landscape, where dialogue and clemency are in decline, but opportunities to improve relations and human rights remain.

See Also: Press Statement: Will the Bell Toll for Shadeed Abdulmateen?

SAN FRANCISCO (September 26, 2022) — Shadeed Abdulmateen, a US citizen, was sentenced to death by the Ningbo Intermediate People’s Court on April 21, 2022. He was convicted of murdering a young Chinese woman, Chen Shijun, with whom he had had a romantic relationship.

Read more here.

See Also: Human Rights Journal, September 20, 2022: Rare Sentence Reduction for Falun Gong Follower

Acts of clemency for Chinese religious and political prisoners have become increasingly rare in recent years. This decrease is the result of Xi Jinping’s hardline approach to both dissent and unorthodox religions, coupled with a sharp drop in judicial transparency. An exception took place in the summer of 2022 when Yu Rongxin (余荣新), a long-time Falun Gong practitioner in Guangdong, was granted a seven-month sentence reduction by the Shaoguan Intermediate People’s Court in June.

Read more here.

See Also: Prisoner Updates 2022 #6: House churches facing continuous crackdown; Hong Kong woman released to Hong Kong, then re-arrested; Activist Long Kehai detained again; Shenzhen activist release

JOHN KAMM REMEMBERS

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s human rights advocacy prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999. Learn about Kamm’s first experiences in China in the 1970s with our timeline.

Names Embedded in Truth, Spoken to Power

On February 11, 2022, I received an email from the Director of Alumni Services and Events at Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS). I was told that I had been nominated to receive the GSAS Centennial Medal, the highest honor bestowed on an alumnus of GSAS, given for significant contributions to society. First bestowed in 1989, the Centennial Medal had been given to around 140 GSAS alumni, including the essayist Susan Sontag and the political scientists Joseph Nye and Francis Fukuyama. I felt humbled and elated to join such a distinguished group of previous awardees. To me, this award was not only a personal honor, but a culmination of Harvard University’s enduring influence on my life and mission.

I enrolled in Harvard for my master’s degree at the age of 23. Though I had only spent two semesters there from 1974-75, they were among the happiest days of my life for both personal and academic reasons. In those two semesters, I learned to read classical Chinese by working through materials I gathered in Kam Tin in Hong Kong’s New Territories with Professor Yang Liensheng, wrote a paper on Chinese foreign trade corporations for Professor Dwight Perkins, and met my first Chinese counterrevolutionary in Professor Jerry Cohen’s seminar on Chinese law, laying the foundation of my human rights activism that began 15 years later.

The Role of Harvard’s Libraries in Prisoner Advocacy

When I was invited to attend the ceremony for the conferring of the GSAS Centennial Medal, I was informed that each of the honorands were allowed to invite a limited number of members of the Harvard community. I focused on inviting librarians who had helped me over the years.

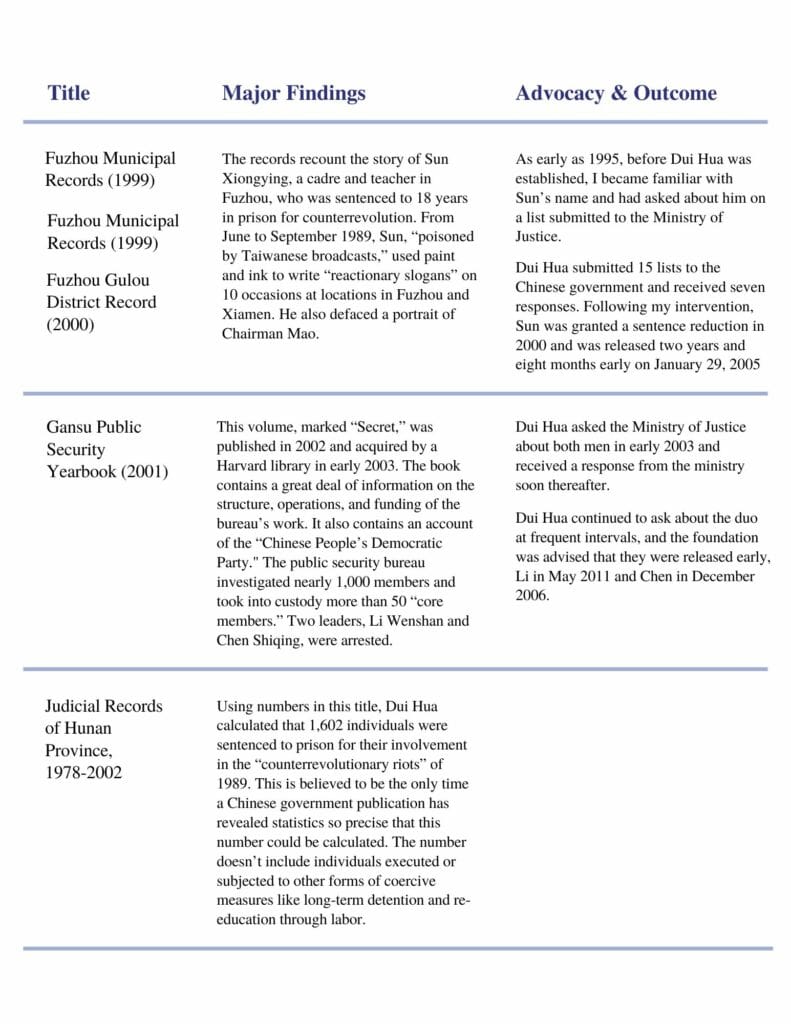

As a human rights organization whose work is founded on its open-source research and advocacy for political and religious prisoners, Dui Hua’s researchers have managed to glean the names of hundreds of political and religious prisoners from the libraries in Harvard. Many of these prisoners were still serving sentences at the time their names were uncovered. Dui Hua placed their names on lists submitted to the Chinese government, after which several received clemency.

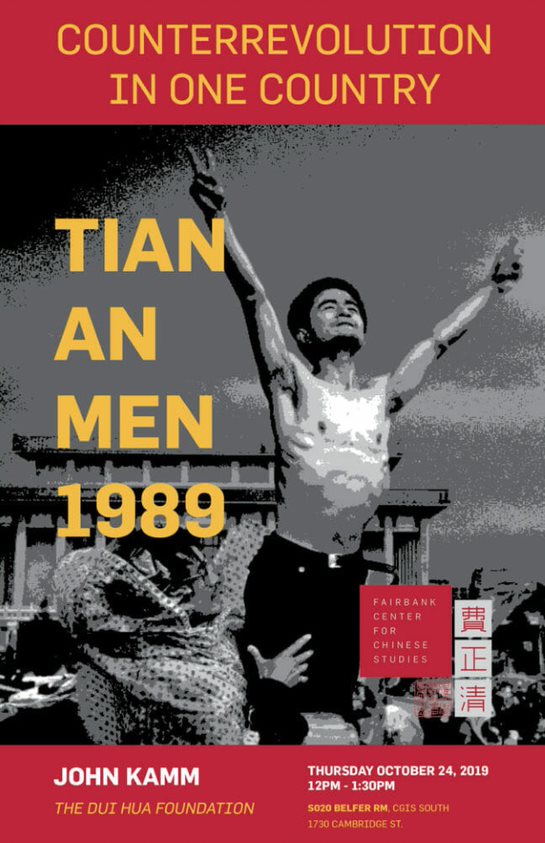

There are four libraries at Harvard holding materials with information on political crime in China: the H.C. Fung Library at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, the Harvard Law School Library, the Harvard Yenqing Library, and the Widener Library, the university’s largest library.

These libraries contain publications such as local gazettes, records, and yearbooks published by state security bureaus, public security bureaus, procuratorates, courts, and justice bureaus. They provide information on and insights into how China deals with political crimes through case examples, regulations, accounts of events (e.g., June 4, 1989), and statistics.

For a time, Dui Hua found useful materials in libraries in mainland China, but that is no longer possible as a result of Covid and political surveillance and harassment of our researchers. Such data is becoming harder to come by even in Hong Kong libraries, including Hong Kong University’s Fung Ping Shan Library and the Universities Services Centre at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. In the years after Dui Hua’s founding in 1999, most of the names were found by the foundation’s researchers, including me, at these two libraries. However, as China has increasingly asserted its control over the former colony, especially in the runup to the imposition of the National Security Law in 2020, materials deemed “sensitive” have been removed from the libraries, and no new ones have been ordered. The collections have been “harmonized.”

The libraries at Harvard are today one of the biggest repositories of names used by Dui Hua in its research and advocacy work and have filled the void left by their Chinese counterparts, but even these libraries are finding it more difficult to acquire volumes on political crime in China.

Some of our most notable findings from Harvard Libraries are listed at the end of this article.

Glorious May at Harvard

During the four days spent at Harvard in May 2022 as the awardee of the GSAS Centennial Medal, I attended several functions, including the medal ceremony on May 25. I also met with professors, including Professor Tian Xiaofei, who nominated me for the medal, Dwight Perkins – under whom I had studied in 1975 – and professors Mark Elliot, Michael Szonyi, and Bill Alford, before whose law school classes I had delivered remarks on several occasions. Of course, colleagues and I spent many fruitful hours in Harvard’s libraries.

The highlight of the visit was the May 25 medal ceremony held at the Faculty Club. It was the first time I had stepped foot in the club. The time came to accept the Centennial Medal. I stepped to the podium where GSAS Dean and classicist Emma Dench, niece of famed British actress Judi Dench, read the citation and handed me the medal.

I was honored to stand alongside three other 2022 Centennial Medalists. They are:

- Neil Harris, PhD ’65, History, for his “pioneering work in shaping the field of cultural history”

- Vicki Sato, AB ’69, AM ’72, PhD ’72, Cellular and Developmental Biology, for her “visionary leadership and life-changing breakthroughs in the biopharmaceutical industry”

- Robert Zimmer, AM ’71, PhD ’75, Mathematics, for his “superlative leadership of [University of Chicago],” and his “principled advocacy for the core mission and values of higher education on the national and global stage”

More about the event:

My award acceptance speech

GSAS Centennial Medal Citation

Given Harvard GSAS’s pivotal role in shaping and aiding Dui Hua’s mission, the award is more than a personal honor. I am grateful to the GSAS, not only for myself but on behalf of the prisoner whose names were unknown but to God until they were found at Harvard — names embedded in truth, spoken to power.

Notable Findings from Harvard Libraries in May 2022

Baoshan Prefecture Public Security Records (2019)

- In late 2021, Dui Hua published Persecution of Unorthodox Religions in China, an exhaustive treatment of a rarely examined subject. Dui Hua identified 41 so-called cults operating in China in recent years. As many as 40 percent of “cult” prisoners in Dui Hua’s political prisoner database are women (women account for 8.5 percent of prisoners in China). Unorthodox religious groups often have extensive international links, and they are for the most part nonviolent.

- Baoshan Prefecture in Yunnan Province has a population of 2.5 million people with a substantial number of ethnic minorities. The Baoshan Prefecture Public Security Records identifies 10 unorthodox religious groups operating in the prefecture in recent years and gives the names of 79 adherents subjected to coercive measures, though few have been sentenced to prison. The four largest groups in terms of adherents subjected to coercive measures are Yi Guan Dao, Falun Gong, the Shouters, and Mentu Hui.

Records of Trials in Gansu Province (2018)

- It is not unusual to find statistics on crime in volumes found at Harvard University libraries. These statistics, when coupled with the set of Supreme People’s Court statistics, help fine-tune our knowledge of how political and religious crimes are handled in China.

Records of Trials in Gansu Province

- Contains tables of cases of endangering state security (ESS) and “using an evil cult to sabotage implementation of the law” (Article 300 of the Criminal Law) tried in Gansu from 1990 to 2015. We learned from the Supreme People’s Court statistics that the vast majority of splittism and inciting splittism cases are tried in provinces with large ethnic minority populations – Xinjiang, Tibet, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Gansu. From the Gansu volume we now know how many such trials took place in Gansu, which sports a large Tibetan population.

- In 1999, the Chinese government banned Falun Gong. The impact of this decision is evident in the table covering Article 300 trials in Gansu. From 1999 to 2015, 486 Article 300 trials took place in Gansu, with more than 40 percent taking place in the four-year period of 2012-2015. The Gansu table on trials of endangering state security uses the term “counterrevolution” to enumerate ESS trials for the entire period. In 1997 China removed the crime of counterrevolution from the criminal law and inserted the crime of endangering state security. The Gansu table confirms what has long been suspected: in the eyes of China’s judiciary, ESS is the same as counterrevolution, a crime defined by motive that is not based on “scientific forensics.”

Jiangsu Province Public Security Records (2010)

- It is widely believed that the Spring 1989 protests were confined to Beijing and a few other large cities. In fact, demonstrations and strikes took place in more than 300 cities and counties across China. The Jiangsu Province Public Security Records chronicles what took place in Nanchang, Jiangxi’s capital, from April 15 to June 25, 1989, including the dates and times of protests and transport disruptions and the names of organizations – chiefly autonomous student federations and independent worker’s unions – that were declared illegal and disbanded.

- Numbers of students and worker leaders and key members of the organizations are given, though no individual names are provided. Ten members of the Nanchang United Worker’s Union were “secretly arrested” but the term “secretly arrested” is not defined.

- The Nanchang account of the spring 1989 protests is but one of many found in Harvard libraries since Dui Hua began its research in 2000. Books published over the last few years rarely mention the events of 1989 as China’s leadership seeks to erase memory of the largest political protests to take place in the country since 1949.

Earlier Findings from Harvard Libraries & Their Contribution to Advocacy

Visit Dui Hua’s timeline “John Kamm Remembers: Fifty Years in China” to read more stories like this, view photos from this period in history, watch videos about the origins of modern US-China engagement, and learn how the decisions of the past are shaping our future.

Subscribe here to receive Dui Hua publications by email.