EVENTS

Kamm Addresses American and Global Audiences in Four Outreach Events

Introducing Dui Hua’s mission of helping at-risk detainees to audiences around the world is a vitally important aspect of the foundation’s work. Hundreds of people attend virtual events at which Executive Director John Kamm describes what Dui Hua does, and how it does it. Kamm always entertains questions from the audience, and these questions, and the answers, open up new areas of understanding and suggest new approaches to advocacy. Outreach events often lead to members of the audience joining the Dui Hua family by becoming donors or sustainers.

In March and April 2021, Kamm addressed four audiences in different virtual events.

On March 24, 2021, Kamm addressed members of the Young President’s Organization (YPO). Founded in 1950, the YPO is a grouping of more than 30,000 members representing 142 countries. To accommodate the global audience spanning all continents (except Antarctica!), the event began at 7:30 AM PST. Kamm spoke of Dui Hua’s origins, its mission, its unique features, and the nature of the foundation’s relationship with the Chinese government. He outlined why businesspeople can make effective human rights activists: “They practice the five P’s – patience, persistence, preparation, persuasion, and passion; they are good at running organizations and raising money, and they know the value of metrics. They are skilled negotiators.”

The same day, he spoke to congregants of Trinity by the Cove Episcopal Church in Naples, Florida. The topic was “A Cross to Bear.” Kamm recounted his journey from businessman to human rights activist and spoke of the importance of scripture passages in informing his work, singling out Matthew 25 – “I was in prison and you visited me.” Prisoners are the lowest of the low who must command our attention, but they receive the highest attention of Jesus Christ.

On March 27, 2020, Kamm engaged members of the US China Catholic Association. He was joined by Father Drew Christenson who spoke on Catholicism’s human rights theology. For his part, Kamm began his presentation by quoting Albert Einstein: “In theory, theory and practice are the same, in practice they are different.” He went on to describe the foundation’s work helping Catholic priests and bishops win their freedom, and spent time briefing the audience on the Jesus Family case (see this month’s John Kamm Remembers), illustrating how practice forms the basis of Dui Hua’s activism.

Finally, on April 8, 2020, Kamm delivered remarks to the University Club of San Francisco, one of the city’s oldest and largest clubs. It was Kamm’s third speech to the club over the last two years. The event was well attended by local dignitaries and individuals involved in US-China relations in Washington, D.C., including Carolyn Bartholomew, Chair of the US China Economic and Security Commission. The title of Kamm’s presentation was “Joe Biden Confronts the China Challenge.”

Dui Hua’s executive director summarized Joe Biden’s China policy by referring to Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s remarks in testimony to Congress and other venues: “Our relationship with China will be competitive when it should be, collaborative when it can be, adversarial when it must be.”

Kamm pointed out that nearly all of former President Trump’s policies on China remain in place. “The charge that China is committing genocide has been repeated, the position that Hong Kong doesn’t deserve special privileges remains unchanged, the tariffs on Chinese goods have stayed in place, curbs on technology transfers to China have increased, and American ties with Taiwan have been strengthened.”

Kamm then transitioned to a discussion of the meeting between American and Chinese officials in Anchorage, Alaska, on March 18. On the eve of the meeting, the United States slapped sanctions on 24 Chinese officials over China’s treatment of Hong Kong, a move that cast a pall over the meeting. The two sides couldn’t even agree on what to call the session: China wanted it to be portrayed as the start of a strategic dialogue, but the United States insisted it was a one-off. There was neither a banquet nor a joint statement. Most important for Dui Hua, the Chinese diplomats proposed a new dialogue on human rights and invited Secretary Blinken to visit China. Mr. Blinken turned down the invitation and rejected the idea of holding a human rights dialogue with China. Lists of prisoners were handed over by the US diplomats.

Constraints on President Biden’s ability to fashion a new China policy are manifold. The two biggest constraints are strong attitudes against China among the American public and Congress. The latter body considered 550 bills and resolutions with China-related content in the 116th Congress. Fifteen passed and became law. Many others have been reintroduced. A focus of the 117th Congress will be the treatment of Uyghurs, including the use of forced labor and forced sterilization and abortion in Xinjiang.

Drawing on polls conducted by Gallup, Pew, the Chicago Council, and YouGov, Kamm’s remarks in the four events demonstrated China’s deep unpopularity in the United States, and the distrust of the country’s leadership. Among the most significant findings are that Americans blame China for Covid-19, nearly half support boycotting the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, 70 percent favor prioritizing human rights over economic ties, and – perhaps most striking – many doubt that Joe Biden can successfully confront the China challenge.

EXCHANGES

Exchanges is a feature that explores Dui Hua’s expert exchanges and dialogues.

“…a 10×10 concrete cell with a metal toilet, concrete bed, and tiny windows…”

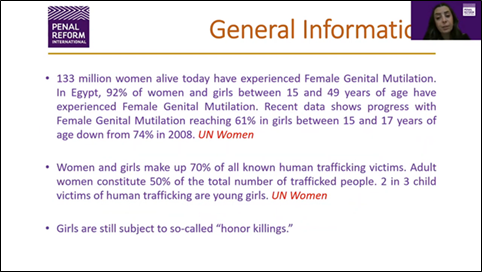

When a girl enters the criminal justice system, what conditions does she face and how are they different depending on where she lives? A rough global sketch of this picture was filled in by panelists during the International Symposium on Girls in Conflict with the Law (GICL).

Speaking about his experience photographing juveniles incarcerated in the United States, photographer Richard Ross commented:

“When you put a ten‑year‑old into a room and a steel door closes, you can hear the sound. You can feel the cold. And then four deadbolts are thrown across. How much damage does it do to these kids?”

This sentiment was echoed by Patricia Lee of the San Francisco Public Defenders Office when describing the current, and relatively new, San Francisco County Juvenile Hall: “There is no difference between an old juvenile hall, a new juvenile hall and adult facility, it serves the same purpose, youth are locked into a 10 x10 concrete cell with a metal toilet, concrete bed, and tiny windows that allow a little light but that you can’t look out of.” Lee stressed that San Francisco is trying to adopt new approaches that include detention alternatives in secure but home-like environments with support services like mental health, family counseling, and skills training.

Panelists from other regions made similar calls for improved support and regulation of juvenile detention facilities. Nafula Wafula, Vice Chairperson for Policy and Advocacy at the Commonwealth Youth Council, shared that the experience of girls incarcerated in the Kenyan system often includes abuse by those who should be protecting them: “There’s a 2016 report that shows that 90 percent of abuses witnessed in police stations by children were perpetrated by police. And the study also found that the police are the most common perpetrators (of crimes against incarcerated girls) in juvenile centers.”

The fact that girls often make up a small portion of the incarcerated population leads to stopgap measures that can put girls at further risk. “In Yemen, girls are kept in detention cells with adult women, while in Jordan, they are kept in tiny, little care centers that do not provide enough space to enable these girls to have proper rehabilitation and reintegration programs that can facilitate their integration into society,” Taghreed Jaber, Penal Reform International’s Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa, said. She described this as a sort of “double discrimination,” in which girls are a minority in a system that ignores their needs as it incarcerates them.

Manfred Nowak, who led the United Nations Global Study on Children Deprived of Liberty stated, “…since the rate of girls is so much smaller than of boys, the criminal justice system, and the prisons, are made for men and boys but not for women and girls. They are more vulnerable to physical violence, in particular, sexual violence, whether it’s by prison guards, virginity testing, etcetera. In general, the conditions in places of detention… lack separation between women and men or the women and girls because often there are only very few girls in a particular prison.”

Meda Chesney-Lind, Chair of the University of Hawaii at Manoa, pointed out a key aspect of why the system seems to be failing girls. “There are big problems when you put girls in facilities and in systems that were really designed for violent boys. Our custody (facilities) lack effective monitoring, and as a result truly horrific conditions have developed in these institutions…there are routine allegations of sexual abuse, excessive idleness, inadequate educational services, allegations of the overuse of isolation, restraints, and chemical agents are also common.”

The Bangkok Rules provide guidelines on what detention facilities for women should include. When implemented, these guidelines protect girls in detention. Reflecting on the progress since the UN’s 2010 adoption of the Bangkok Rules, Jaber said, “I will tell you that as a practitioner in this field, I am a little bit disappointed. The number of girls who are coming in contact with the law and are in detention facilities is increasing, and the measures taken by states towards creating a protective environment and having full compliance with the rules is really shy.”

Across the board, panelists stressed that current juvenile justice systems were inadequate, ignoring the needs of girl detainees and leading to further victimization and stigmatization. The notion that many girls in detention would be better served by addressing the underlying factors of their criminal behavior was a recurring, and enduring, call to action. Drawing on his research for the UN, Nowak concluded “…the root causes for so many kids in detention are the lack of an effective child welfare system. Most of these children should actually be treated by the child welfare system and not in the criminal justice system.”

To learn more about the panelists, watch their individual webinars and read a full list of recommendations visit girlsjustice.org.

PUBLICATIONS ROUND UP

Featured: Human Rights Journal, May 18, 2021: Hefty Prison Sentences for Selling Audio Bibles

Dui Hua’s research into court judgments found that four Christians who sold USB flash drives containing encrypted sermons were sentenced to two to six years in prison in Henan Province on December 2, 2020. Three of them were convicted of illegal business activity and another of “concealing crime-related income.” Their trial was concluded just a few days before overseas Christian groups reported another illegal business activity case in Shenzhen where five Christians were facing trial for selling audio Bibles amid China’s campaign to “eradicate pornography and illegal publications.”

In April 2018, China’s popular online retailers including JD.com, Tabao, and Amazon.cn began pulling Bibles from their stores. Although the Bibles are still printed in China, they are legally available only at state-sanctioned church bookstores and cannot be sold through normal commercial channels. Individuals who breach the rules to sell the Bibles online or in physical bookstores risk being charged with illegal business activity under Article 225 of the Criminal Law.

See Also: Human Rights Journal, May 13, 2021: Transparency in Inciting Splittism Trials

China’s Fifth Judicial Reform Plan Outline in 2019 committed itself to an “open, dynamic, transparent, convenient sunshine judicial system.” Although much progress has been made in the number of court rulings and judgments posted online, the level of transparency varies by case type, crime, and region. Criminal cases classified as endangering state security (ESS) are among the least transparent.

Despite being a restive region, Ganzi, or Garze, a Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture occupying the western arm of Sichuan Province, is the top region in all of China with the highest number of publicly disclosed ESS court rulings and judgments. In Ganzi, 26 of the 28 publicly disclosed ESS cases concerned the crime of inciting splittism (煽动分裂国家罪). Dui Hua previously reported that the Ganzi Intermediate People’s Court convicted nine Tibetans of inciting splittism between June and August 2020. In the last four months of 2020 the same court released five more judgments involving six defendants who were tried for the same crime.

See Also: Prisoner Updates 2021 #5, Part I: CGTN documentary on “war on terrorism in Xinjiang”; “Two-faces” officials; fate of Ilham Tohti student learned; CCTV claims to reveal money man behind Hong Kong protests

See Also: Prisoner Updates 2021 #5, Part II: Retired police officer sentenced to twelve years for defamation and other crimes; Appeal rejected for citizen journalist who exposed corruption; Former party-school teacher released

JOHN KAMM REMEMBERS

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s human rights advocacy prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999.

Resurrecting the Jesus Family

I was quite surprised when the State Council Information Office (SCIO) and the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) agreed to the proposal I made at our January 1995 meeting to accept four lists of prisoners during the year, one each quarter. I had prepared and handed over a list of 25 prisoners, leaving three more lists of 25 names to be submitted in 1995.

This was four years before Dui Hua existed, and long before the foundation had set up its political prisoner database (PPDB). Since the early 2000s, I have relied on the PPDB to draft prisoner lists, but in the 1990s I had to rely on conversations with political activists, family members of political prisoners, and NGO publications to identify names for my lists.

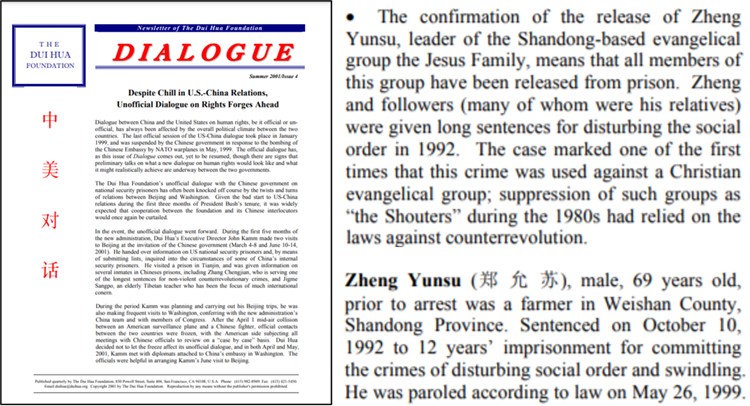

Among the names I included on my lists was Zheng Yunsu, leader of a Jesus Family congregation in Shandong Province who was detained in May 1992 and subsequently sentenced in September 1992 to 12 years in prison for disturbing the social order and fraud. I found his name and accounts of his detention and sentencing in Detained in China and Tibet, published by Human Rights Watch in February 1994, and The Imprisonment and Harassment of Jesus Family Members in Shandong Province, published by Amnesty International in October 1994. I placed Zheng Yunsu’s name on my fourth quarter list, which I faxed to the Ministry of Justice in November 1995.

Subsequent to Zheng’s detention, Chinese police moved in and detained dozens of other Jesus Family members, including Zheng’s four sons, and demolished their church buildings in Duoyiguo Village in Shandong Province. The arrests and destruction of church properties were eerily reminiscent of the attack by Chinese police on Youtong Village in Hebei in April 1989. A Trappist priest, Pei Ronggui, was detained, Church property demolished, and two villagers killed in the attack. Pei was subsequently sentenced in 1991 to five years in prison for “disturbing the social order.” He was granted early release on March 31, 1993, following a brief campaign of spirited intervention with my interlocutors.

Instead of being put in prison for counterrevolution, both Pei Ronggui and Zheng Yunsu were imprisoned for disturbing the social order, a precursor of “using a cult to sabotage implementation of the law,” Article 300 of the Criminal Law amended in 1997.

The Jesus Family: A Brief History

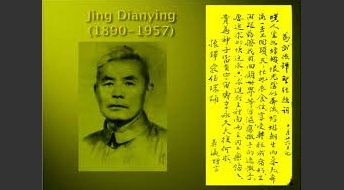

The Jesus Family is an indigenous Christian communitarian group that emerged in Shandong Province during the 1920s. Although it was influenced by Pentecostal missionaries, the Jesus Family is not a Pentecostal church. Founded by Jing Dianying, a charismatic Christian who was raised in a traditional Confucian family that practiced Buddhism and who later attended a Methodist high school, the Jesus Family expanded rapidly throughout China, surviving and even thriving during the Japanese occupation and the Chinese civil war that resulted in the defeat of Nationalist forces in 1949.

The Jesus Family emphasized simple living, poverty, communal sharing, piety, and prophesy. It emphasized prayers and singing of psalms. It reportedly rose to more than 125 congregations and 20,000 members in China by 1949. Although concentrated in Shandong, families existed in many other provinces.

After 1949, the Jesus Family leadership embraced the officially sanctioned Three-Self Movement, and for a while its activities were condoned, even praised by the Chinese government and communist party. However, the sect’s rapid growth and communitarianism came to be seen as a threat to the party, and in 1952 Jing was arrested and sentenced to prison where he developed cancer. Jesus Family properties were destroyed and the 500 members who lived in Mazhuang were dispersed throughout Shandong.

Jing died shortly after being granted medical parole in 1957. The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) saw this unorthodox Christian group largely disappear. It was only after the reform and opening period began in 1979 that the church reemerged. It spread rapidly. In Ding’s home village, Mazhuang, the family reoccupied 43 acres of land, established a church, and grew crops. Eventually an eye hospital was established. It still serves the Mazhuang and surrounding communities and is deeply appreciated by both local residents and the party.

One of the biggest areas of growth took place in Duoyigao, a village near Weixian City in western Shandong. There and in surrounding villages, the family, under the leadership of Zheng Yunsu, counted around 3,000 congregants. Services, including baptisms, were attended by more than 1,000 believers. The congregation supported itself by raising rabbits, making shoes, and growing crops for its own consumption and to give away to those in need. Family activities alarmed local security forces, which subjected the group to surveillance, including using a helicopter to monitor gatherings. Members faced harassment and short detentions.

Attacks on Duoyigao Village, May-June 1992

On May 19, 1992, police disrupted a service led by Zheng Yunsu in Liuzhuang Village, a community with many Jesus Family congregants not far from Duoyigao Village. Zheng was spirited away from the service before police could take him into custody, but the next day, Zheng surrendered to police in Shandong’s provincial capital, Jinan. Not long afterwards, Zheng’s four sons were taken into custody. Zheng and his sons were paraded through Duoyigao Village and surrounding villages with placards hung around their necks identifying them as Jesus Family believers.

On June 18, 1992, 40 truckloads of police descended on Duoyigao Village. Several buildings were destroyed, and possessions – including bicycles, machinery for making shoes, furniture, bedding, clothing, livestock, and grains – were seized. On June 20, 1992, the police returned and detained more than 20 Jesus Family members. On July 10, 1992, another ten members were detained.

On October 10, 1992, Zheng Yunsu was convicted of fraud and disrupting social order by the Weishan District Court. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison and placed in Shandong Number One Prison. His four sons were sentenced to three-year terms of re-education through labor. Most other Jesus Family detainees were released after they confessed their crimes and agreed to stop their religious activities. Those released, and other members of the Jesus Family, wrote a detailed account of what they had gone through. This was provided to Amnesty International in London which published an urgent appeal based on this information in August 1993. This appeal formed the basis of the information published by Human Rights Watch in 1994, which in turn led to my including Zheng Yunsu’s name on my November 1995 list submitted to the SCIO and the MOJ.

Nine months after I submitted the November 1995 list with Zheng Yunsu’s name on it, he was granted an 18-month sentence reduction. Further advocacy resulted in Zheng Yunsu being released on parole on May 26, 1999, seven years into his 12-year sentence.

Strategy to Free Zheng Yunsu

I adopted a multi-pronged strategy for advocating on Zheng Yunsu’s behalf. I placed him on my lists and raised his name in conversations with Chinese officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the SCIO, the MOJ, and the Religious Affairs Bureau. I also put his name on lists of countries having bilateral human rights dialogues with China, notably the United States. I encouraged members of Congress to reference Zheng in their letters Chinese leaders. Finally, I used the visits of senior American religious leaders to China to raise Zheng’s name.

Following the November 1995 list on which I put Zheng’s name, I placed Zheng’s name on a list of 24 prisoners submitted to the MOJ in October 1997, immediately prior to President Jiang Zemin’s state visit to the United States, and on a July 1998 list of religious prisoners eligible for parole (they had completed half of their sentences). I gave this list to the Department of State for use in its January 1999 bilateral human rights dialogue with China.

In addition to referring to the November 1995 list that included Zheng’s name in Congress members’ letters to the Chinese government urging a resumption of the Prisoner Information Project, several members either attached their own lists of religious prisoners on which Zheng’s name was included or raised Zheng in their conversations with Chinese officials in the United States or China.

During the October 1997 state visit of Jiang Zemin to the United States, Jiang Zemin and President Clinton struck an agreement that a group of American religious leaders would be invited to visit China in early 1998.

The group, led by Rabbi Arthur Schneier, president of the Appeal of Conscience Foundation, and including the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Newark Theodore McCarrick and the president of the National Association of Evangelicals Reverend Don Argue, spent two weeks in China in February 1998. They met with President Jiang in the Great Hall of the People; Rabbi Schneier presented President Jiang with a gold-embossed Torah. They also met with Ye Xiaowen, director of the Religious Affairs Bureau. They provided Ye with a list of 30 religious prisoners drawn up in consultation with the United States government and human rights activists, including me. Ye promised to give answers.

In January 1999, Rabbi Yechiel Eckstein, one of America’s preeminent rabbis, traveled to China to lobby the Chinese government to release imprisoned Christian pastors. He forcefully took up the cause of Zheng Yunsu in discussions with Director Ye Xiaowen. Four months after the rabbi’s visit, Zheng Yunsu was paroled.

Aftermath

Little has been written about what happened to the Jesus Family after 1997. What has been written suggests that the Jesus Family has largely disappeared – disbanded, marginalized, affiliated with various house churches, or absorbed into the government-approved Three-Self Movement. In his book Pentecostals in China, published in September 2015, Robert Menzies maintains that the Jesus Family exists in non-communitarian form in various parts of China. “It’s quite small,” he writes.

An American religious scholar living in Hong Kong disagrees. This man, who visited the Mazhuang eye hospital in the early 1990s and has stayed in touch with the faith community in Shandong, states that the Jesus Family remains active in the public space. According to his account, as of the end of 2019, the Jesus Family enjoys good relations with the Three-Self Movement’s Shandong Christian Council. Zheng Yunsu, now in his late 80’s, was in good health and continuing his work. He was not in trouble with the Chinese government. He was well and at peace. His faith had set him free.