EVENTS

Bipartisan Consensus Against China in US Congress

Fueled by public anger over China’s behavior, American lawmakers have enacted laws that signal a tougher approach to Beijing, and more are being considered. In a polarized election year, there are few areas for cooperation between the Democratic-majority House and the Republican-led Senate and White House. However, in the last two years, legislators from both parties have successfully advanced more China-related legislation than in any other period in recent history.

Newsworthy Developments

The Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act (HKDRA) was signed by President Trump on November 27, 2019. It authorizes sanctions on mainland and Hong Kong officials who are known to have committed human rights abuses against Hong Kong people, and it requires the State Department to annually report on Hong Kong’s autonomous status. Representative Chris Smith (R-NJ4) and his Senate counterparts introduced the bill after the 2014 Umbrella Movement and democracy protests in Hong Kong, but it did not gain traction in that session of Congress or the two subsequent ones. The bill finally came to a vote in October 2019, after a proposed extradition bill sparked civil unrest in Hong Kong.

In addition to the HKRDA, the current Congress has also agreed to a resolution condemning the People’s Republic of China for violating its obligations to Hong Kong (H.Res. 543) and passed S. 2710, which prohibits the export of tear gas, pepper spray, rubber bullets, and other crowd control munitions to Hong Kong. The PROTECT Hong Kong Act, a bill with similar munitions restrictions but more human rights language, passed the House on October 15, 2019 and awaits action in the Senate. Two other human rights bills, the Hong Kong Policy Reevaluation Act of 2019 and the Hong Kong Be Water Act, have been introduced into the House and Senate.

On March 26, 2020, the president signed the Taiwan Allies International Protection and Enhancement Initiative (TAIPEI) Act, which aims to help Taiwan gain participation in international organizations and to discourage Taiwan’s allies from cutting ties with the island due to pressure from Beijing. Ten other Taiwan-related bills have been introduced in this Congress. Two of these bills, the Taiwan Assurance Act of 2019 and H.R. 353, have passed the House. Both advocate for Taiwan’s presence at the World Health Organization, so it would be noteworthy if either moved to a vote in the Senate, as there have been high-profile disputes between Taiwan and the WHO during the COVID-19 crisis.

No previous Congress in the last decade has introduced more than 10 Taiwan-related bills, and the few laws they managed to enact mostly called for executive branch strategies rather than substantive congressional action (with the exception of the 2018 Taiwan Travel Act). In the same period, lawmakers proposed 21 simple and concurrent resolutions to express Congress’ sentiment towards Taiwan, but not a single one was agreed to until H.Res. 273 in 2019, which reaffirmed US commitment to Taiwan.

Behind the Headlines

When Democrats retook the House of Representatives in the 2018 midterm elections, Dui Hua anticipated that, despite the ideological divide, there would be political momentum to enact legislation concerning China. The recent passage of landmark bills on Hong Kong and Taiwan reflects this, and a thorough examination of China-related legislation over the last decade indicates that this is more than a passing political moment.

Since the 116th Congress began in January 2019, at least 194 bills and resolutions with policy implications for China have been introduced in the House and Senate. In the previous session, 128 China-related bills and resolutions were introduced, and the early 2010s saw an average of just 80 per session. Overall lawmaking has not significantly increased in the same period, so the percentage of legislation concerning China has crept up from 0.72 percent to 1.64 percent of the total.

Of the 641 bills in Dui Hua’s data set, 361 are only partially focused on China. Keeping track of this broadly focused legislation is important for two reasons. First, policies impacting China are more likely to be implemented if they are bundled into more comprehensive resolutions or bills. Over the last decade, on average only 14 percent of solely China-focused bills and resolutions were enacted into law or passed at least one chamber of Congress, whereas 27 percent of bills and resolutions with a broader scope were enacted or agreed upon.

Secondly, the spillover of China-related policies into seemingly unrelated legislation shows that Congress is engaging China with more of an “all of government” approach than confining Chinese policy to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee or the House International Relations Committee. Whereas past China-related legislation primarily concerned diplomacy, defense, trade, and immigration, a significant number of bills and resolutions introduced during the Trump administration also deal with crime (such as S. 2563: ILLICIT CASH Act and H.R. 2483: Fentanyl Sanctions Act) and technology (like S. 3455: No TikTok on Government Devices Act and S. 1459: China Technology Transfer Control Act of 2019).

Measuring the raw quantity of bills and resolutions passed is not always the best way to gauge the impact of legislation. Pew Research has found a trend of fewer “substantive” and more “ceremonial” legislation in recent years. Applying a similar methodology, Dui Hua’s research found that legislation which substantively affects China now makes up a record 70 percent of China-related legislation, compared to 20 percent of the legislation with a symbolic role and 10 percent with an information-gathering role (that is, authorizing reports and investigations to inform future China-related decisions).

Reasons for Success

Of all the bills introduced into the 116th Congress, 26 with China-related provisions have already been enacted or bundled into enacted legislation. Over the last decade, on average only 12 China-related bills were enacted on their own or via other legislation per session. Likewise, this Congress has agreed to an above-average number of simple and concurrent resolutions, expressing its stance on Chinese telecommunications, Taiwan, freedom of the press, the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, Hong Kong, and Dr. Li Wenliang, the Chinese doctor who identified the severity of the COVID-19 outbreak in late 2019. All this is despite the fact that this session is months away from its final quarter, during which, on average, half of all legislation is enacted.

While there are many arguments that Congress’ priorities fail to match American public opinion, lawmakers’ increasingly strong stance on China is both supported by their constituents and an area for common ground across the aisle. When last surveyed by Pew Research, Republicans and Democrats had sharply divided views on America’s top foreign policy priorities, but both agreed on China as a mid-level priority. Since then, Americans across the political spectrum have adopted even more unfavorable opinions on China (see box below). Accordingly, the share of China-related bills introduced with bipartisan support (including at least one co-sponsor from the opposite party) has climbed back to around 65 percent during the Trump administration, up from below 60 percent during the last three sessions of the Obama administration.

It is worth keeping an eye on bills awaiting action, particularly those concerning public health. On March 19, 2020, long-time China hawk Senator Marco Rubio (R-Fl) introduced the Strengthening America’s Supply Chain and National Security Act. The bill, which has bipartisan and bicameral support, aims to lessen America’s reliance on China for pharmaceuticals and medical equipment. It is likely to pass Congress and be enacted into law this year.

Another fourteen bills have already passed one chamber of Congress. They include the aforementioned acts and resolutions on Taiwan, three defense bills that increase reporting on China, two bills investigating Chinese financing, restrictions on government use of Chinese drones and IT equipment, and, most prominently, the Tibetan Policy and Support Act of 2019 and the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act of 2019.

The Tibetan Policy and Support Act passed the House with a supermajority of 392 votes on January 28, 2020. It would be a reauthorization of the Tibetan Policy Act of 2002 and calls for more funding for Tibetan NGOs, a US consulate in Lhasa, and Chinese non-interference in the appointment of the next Dalai Lama. Based on mathematical correlations, Skopos Labs estimates the bill to have a 78 percent chance of being enacted.

The Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act, a response to the reported mass incarceration of Uyghurs in China’s Xinjiang province, passed the Senate on September 11, 2019 with unanimous consent. The House amended the bill to be even stronger and passed it by near-unanimous consent on December 3, 2019, sending it back to the Senate.

If enacted, the bill would impose sanctions against Chinese officials, including politburo member Chen Quanguo, and direct national intelligence agencies to report on the crackdown in Xinjiang, as well as threats against Uyghurs and Chinese nationals in the United States. The legislation builds on a similar attempt in the previous Congress, and two bills against Uyghur forced labor were also introduced on March 12, 2020. The Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act has drawn furious remarks from Chinese officials, threatening trade talks, and its passage would likely provoke China to react even more strongly than it did after the passage of the HKHRDA.

On September 30, 2019, the Pew Research Center released a Global Attitude Survey that revealed that public opinion of China had dropped in 17 countries that were surveyed in both 2018 and 2019, while opinion had risen in nine. China’s favorability had fallen by double digits in eight countries, including the United States, Canada, Sweden, and Australia.

On March 2, 2020, Gallup released its most recent poll of American attitudes towards China. It revealed that public opinion towards China had plummeted by 20 percentage points in the two years since 2018, reaching a level lower than even the poll taken in the aftermath of June 4, 1989.

Most recently, Harris released a poll of 1,993 American adults taken from April 3-5, 2020. The poll reveals deep distrust of China over its handling of the coronavirus pandemic, and strong support for a tough policy towards China. Key findings include:

- Fifty-eight percent say that the Chinese government is to blame for the spread of the coronavirus to the United States;

- Seventy-seven percent feel that China’s reporting on the coronavirus has not been accurate;

- Fifty-two percent agree with President Trump referring to the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus;”

- Sixty-nine percent favor President Trump’s trade policy towards China, but 50 percent favor an even tougher policy;

- Fifty-four percent think that China should pay for the spread of the virus;

- By a bare majority (51 percent to 49 percent), Americans do not believe that China will purchase $250 billion of American goods as required by the “Phase One” trade agreement between the two countries;

- Seventy-three percent think that, if China does not live up to the agreement, the United States should reimpose tough tariffs on China;

- Seventy-one percent think that American companies should pull back manufacturing operations from China; and

- Eighty percent feel that, if China has been underreporting cases and deaths, President Trump and/or Congress should impose economic sanctions.

PRISONER UPDATES

Despite a drop in new cases, COVID-19 continues to affect inmates, including those who were jailed for exercising free speech. Prominent rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang (王全璋) has yet to be reunited with his family in Beijing after completing his four years and six months’ sentence for subversion on April 5. Wang, who has repeatedly tested negative for COVID-19, was forced into 14-day quarantine in his hometown Ji’nan, Shandong. His wife Li Wenzu worries that the authorities will continue to use extrajudicial measures to hold Wang for an extended period, as they have with many dissident lawyers and activists over the years.

Another notable case concerned coronavirus critic Ren Zhiqiang (任志强), a former real estate tycoon who is being investigated in Beijing for allegedly “seriously violating law and discipline.” Observers believe that he is held under a form of detention known as liuzhi, under which detainees are kept incommunicado without access to lawyers or families for up to six months. Ren went missing on March 13, 18 days after he published an essay on social media in which he denounced Xi Jinping’s missteps in containing the coronavirus in Wuhan. In the essay, Ren also mocked Xi as “a clown stripped naked who insisted on continuing being an emperor.”

On March 31, Qi Yiyuan (祁怡元) and Zhang Pancheng (张盼成) were sentenced to 24 months and 18 months’ imprisonment, respectively, for picking quarrels and provoking trouble in Beijing. The duo, who are in their twenties, made videos critical of Xi. Qi posted a video of himself wearing an “anti-Xi” and “anti-Communist Party” t-shirt calling for freedom of expression, the release of rights lawyers, and the reinstatement of rights lawyers who were stripped of their licenses. In a separate video, Zhang called for the release of Dong Yaoqiong (who was sent to a psychiatric hospital for splashing ink on a poster of Xi in July 2018), Yue Xin (a vocal supporter of the Jasic worker strike in the summer of 2018), and over a million Uyghurs who are involuntarily held in facilities officially referred to as vocational training centers.

Despite hailing warmer ties with Japan in recent years, China has reportedly detained at least 15 Japanese nationals on various charges since 2015, including espionage. Chinese nationals with connections to Japan are also at risk of being accused of endangering state security. The latest case concerns Yuan Keqin (袁克勤), a professor who conducts research on Japanese and Chinese politics at the Hokkaido University of Education. Yuan, who was born in China and later became a permanent resident of Japan, went missing in June 2019 on his trip to China for his relative’s funeral. On March 26, 2020, the spokesperson of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded to a reporter’s inquiry that Yuan had confessed to spying. However, details of what he did and where he is held have not been disclosed at the time of writing.

PUBLICATIONS ROUND UP

Featured: Human Rights Journal, March 30, 2020: China’s Criminal Trial Statistics: Taiwan-Related Cases, Part I

The self-ruling island of Taiwan has been a thorn in China’s side since the island’s breakaway in 1949. Viewed by China as a territory awaiting reunification, Taiwan is a potential military flashpoint, with both sides of the strait conducting clandestine intelligence operations in each other’s territory.

Since Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-wen first took office in 2016, spy scandals have re-emerged as an irritant in cross-straits relations. In 2017, Taiwanese news media sources said that there were approximately 5,000 Chinese spies in Taiwan, although the Chinese government dismissed these reports. In September 2018, China’s state security departments announced that over a hundred Taiwanese spy cases had been prosecuted amid its “Thunderbolt 2018” campaign. China accused Taiwan of luring mainland students studying in Taiwan with “money, love and friendship,” as well as using honey traps to recruit them as spies.

The “Taiwan threat” has long been a major part of the Chinese Communist Party’s rhetoric, but how it articulates this perceived danger has varied. This post, the latest in Dui Hua’s series using statistics from the Supreme People’s Court, compares public information sources about Taiwanese espionage cases with court statistics. Much like in its coverage of Hong Kong-related cases, ambiguity and inconsistencies in reporting suggest an opaque system prone to opportunistic interpretations of criminal law.

Continue reading about Taiwan-related cases here.

JOHN KAMM REMEMBERS

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s human rights advocacy prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999.

Mission to Beijing: April 1992, Part I

As winter turned to spring in 1992, Chinese officials increasingly turned their attention to the possibility that the country’s coveted trade privilege – Most Favored Nation (MFN) status in the United States – might be removed if the White House changed hands in November. Deng Xiaoping’s friend George H. W. Bush, the incumbent, was expected to be a shoo-in on account of the success of the Gulf War. But after Super Tuesday, March 10, 1992, polls suggested that in a three-way race involving President George H. W. Bush, Arkansas Democratic Governor Bill Clinton, and independent Ross Perot, Bush would poll less than 50 percent.

Furthermore, in December 1991, Beijing had applied to hold the 2000 Olympics, and officials knew full well that its human rights record would prove to be an impediment. I decided to exploit their fears and ambitions by planning a week-long trip to Beijing beginning April 5, 1992.

It would prove to be a remarkable trip, marked by meetings with senior officials and opportunities to intervene on behalf of political and religious prisoners, the latter mostly Catholics. I would also be given information on China’s most famous political prisoner, Wei Jingsheng, and Wang Dan, a leader of the June 4 protests. Concerning Wei, this would be the first time that the Chinese government would address his living conditions, health, and state of mind.

I flew up to Beijing from Hong Kong on the afternoon of April 5. I was picked up by my driver and taken to the Great Wall Sheraton Hotel, near the Embassy District. The Great Wall Hotel was managed by a friend who offered me a generous rate and lots of hospitality, including the occasional drink at the hotel’s well-stocked bar.

The next day, April 6, I met with my host, Vice Chairman of the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT), Liu Fugui. This was followed by a meeting with the Deputy Director of the American and Oceanian Department of the Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations and Trade (MOFERT), Shi Jianxin. These meetings focused on the situation in Congress with respect to MFN, which was grim, in my estimation.

In the afternoon I met with the Supreme People’s Court and, later, Luosang Chinai, a Tibetan official who was a senior official in the Religious Affairs Bureau (RAB, now the State Administration of Religious Affairs). He was accompanied by a lady who was in charge of the department overseeing Roman Catholics, known as the Second Department.

At this meeting I pressed for the release of elderly Catholic clerics Bishop Liu Guandong, president of the underground Catholic Bishops Conference, serving a sentence in a reeducation through labor (RTL) camp, Father Jin Dechen, serving a 15-year sentence in prison for counterrevolution, and Monsignor Wang Yijun, one of China’s longest serving religious prisoners, then serving a three-year sentence in an RTL camp. Luosang Chinai seemed sympathetic.

Six weeks after this meeting, all three of the clerics, held in facilities around the country, were released on the same day.

That evening I was hosted to a welcome banquet by the CCPIT’s Liu Fugui. Mao Tai, the fiery, sorghum-based spirit (120 proof) was poured liberally, and not wanting to be a bad guest, I partook liberally. I returned to the Great Wall Sheraton, where I was met by my friend the manager. We repaired to the bar where we had shots of Black Label chased by beer. Bad idea.

Vice Minister “Gold Prison”

The next morning, I woke up with a ferocious headache. I had a bolt of caffeine and soldiered on, as businesspeople do, meeting my driver and being driven to the nearby Kunlun Hotel, said to be owned by China’s Ministry of State Security. Up the escalator, I was ushered into a large room where I was met with Ministry of Justice Vice Minister Jin Jian (synonymous with “gold prison”) and the Director of the Reform through Labor Bureau (now the Prison Administration Bureau) Wang Mingdi. I had met Wang in October 1991, so we were “old friends.” Wang was a tough prison official who sported a cauliflower ear.

I sat down on a plush chair with a doily as a head rest. A translator sat between me and the vice minister. There were two notetakers next to Wang Mingdi.

After an exchange of pleasantries, Vice Minister Jin came straight to the point. “We have decided to give you information on any prisoner you ask us about, to the best of our ability.” I was told that this was the first time they were offering this privilege to a foreigner.

I looked at Wang Mingdi. He was seated by a table on which there was a big stack of files, each apparently containing information on prisoners.

I suggested to the vice minister that we could save a lot of time if Mr. Wang would simply give me the files on the table next to him.

Vice Minister Jin did not like this idea. “You need to ask us about individual prisoners, using the full name. Don’t just ask about Mr. Wang in Beijing or Mr. Li in Shanghai. Do you have any idea how many Mr. Wangs live in Beijing and how many Mr. Li’s live in Shanghai?!

“Please tell me about Wei Jingsheng,” I replied.

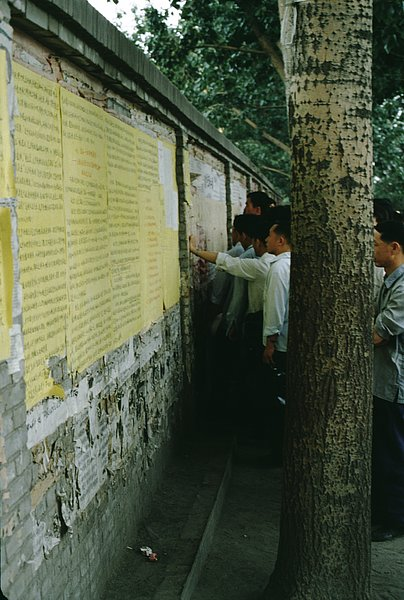

Wei was at the time China’s best-known political prisoner. An electrician and former soldier who had been working at the Beijing Zoo since 1973, Wei was prominent in the 1978 Democracy Wall movement. On December 5, 1978, Wei posted an essay, “The Fifth Modernization,” on Democracy Wall, a stretch of wall surrounding a bus station in Beijing’s western district. Citizens took to the wall and put up “big character” posters in a burst of free speech not seen since the Cultural Revolution – and not seen since. I frequented the wall on many occasions in late 1978; at that time, I was staying at nearby hotels, including the Fuxing, during trips to sell chemicals and technology.

Wei’s poster caused a sensation. It rebutted Deng Xiaoping’s Four Modernizations policy and criticized Deng by name, calling him a dictator. (Deng had called for the modernization of industry, agriculture, national defense, and science and technology.) Wei Jingsheng proposed a “Fifth Modernization” — democracy. Soon Wei was being interviewed by foreign journalists, helped by his able assistant Tong Yi.

Wei was detained in 1979 and subsequently sentenced to 15 years in prison for counterrevolutionary crimes. The Chinese government had said nothing about him for more than a decade.

Wang Mingdi picked a file from the stack and began to read: “Wei Jingsheng, male, Han, born in 1950, middle school education, worker. Sentenced to 15 years imprisonment and three years deprivation of political rights in October 1979. He is currently serving his sentence in a reform through labor camp.”

I asked where Wei was serving his sentence. “What can you tell me about the conditions of his imprisonment? Is he being held in solitary confinement?”

“He’s serving his sentence in a reform through labor camp in Tangshan, Hebei Province. It is not correct to say he’s being held under solitary confinement. His cell has two rooms. He has one room to himself. This room opens onto another room where there are guards. He eats his meals and watches television in this room. He is allowed out for fresh air, and he enjoys gardening. He has been exempted from physical labor.”

“Tell me about his health,” I asked.

Wang replied: “He is in good health, although he smokes a lot. Contrary to reports in Western media, he is not being mistreated. He has not lost his mind. He has not lost his hair nor all his teeth. He likes to stay up late debating with the guards. Wei is a very intelligent, well-informed man, but he is very stubborn. He refuses to admit his guilt or express regret.”

I asked if he could be considered for early release from prison. Wang was blunt. “Unless he changes his attitude, it is unlikely that he will be granted a sentence reduction or parole.”

Once Wang finished talking about Wei, I asked about Wang Dan, a student leader of the Tiananmen Square protests in the spring of 1989. I was told that Wang, like Wei, was proving difficult to reform. He liked reading and stayed mostly in his cell. He too had been exempted from physical labor. He was not being mistreated.