Soon after Dui Hua registered as a non-profit in April 1999, I and my colleagues began visiting the University Services Center (USC) on the campus of the Chinese University of Hong Kong in Shatin. We focused on finding the names of political prisoners in Chinese books and magazines; many of the prisoners had escaped the attention of researchers and activists outside of China.

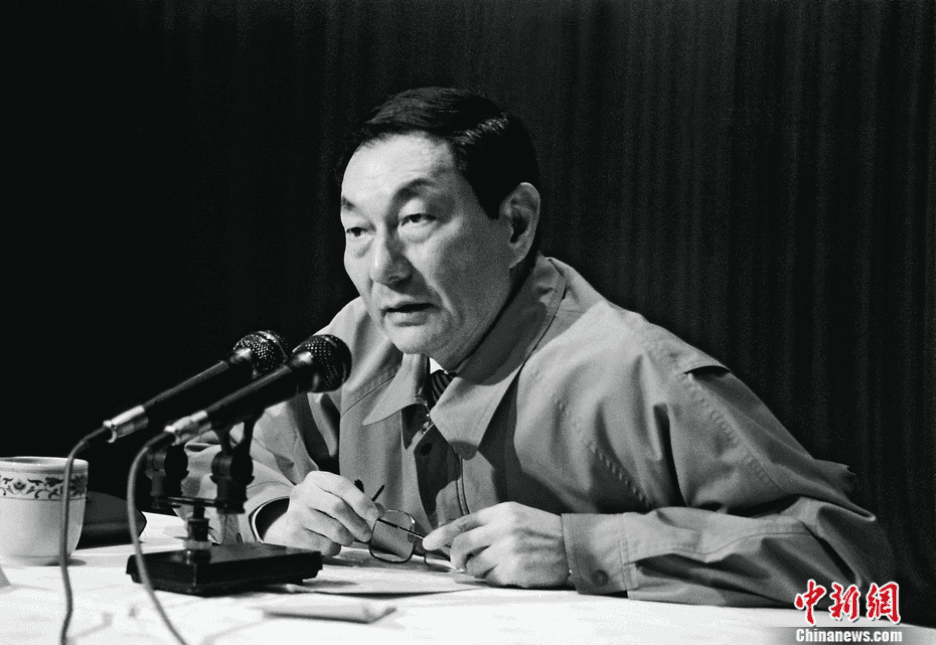

An early find was two issues of People’s Police, a publication that extolled the work of Shanghai’s public security bureau in breathless accounts of their heroism. The issues told the story of Yu Rong (余蓉), then 35, whose father died in prison after being sentenced for counterrevolution. A recidivist who had served sentences for minor crimes, Yu had a penchant for dropping leaflets and other objects from tall buildings in multiple locations in Shanghai.

Copy of People’s Police 1990, Issue One, “A major reactionary pamphlets case in Shanghai”.

Image source: Dui Hua

In all, Yu disbursed 1,450 leaflets by dropping them from tall buildings or leaving them in public toilets over a 108-day period that began with the suppression of protests in Beijing and other cities in the Spring of 1989. The magazine claimed that Yu Rong’s actions constituted the biggest crime of its kind in Shanghai since 1949.

All of the leaflets had been written on the pages of elementary and high school textbooks published in the early 1980s. All had been written by the same hand using a black-ink brush.

Then Shanghai Mayor and Party Secretary Zhu Rongji. Image Source: Sohu.com

At a time of social tensions when crimes were soaring, Shanghai’s mayor, Zhu Rongji, took charge of efforts to capture Yu. He ordered the police to solve the case immediately and deployed hundreds of policemen to accomplish the task.

Zhu had gained a reputation as a calming, moderate voice. After the June 4 protests – which eventually resulted in the execution of four individuals in Shanghai who had attacked a train – Zhu went on local television, removed his glasses and claimed to have lost his speech. He appealed for calm. Zhu went on to build a reputation as an economic reformer and was the architect of China’s effort to join the World Trade Organization. But he was also a brutal reformer who ordered the executions of individuals involved in a big car smuggling scandal in Hainan.

Flooding the Zone

In those days, the police did not have access to forensic tools like fingerprints and DNA testing. Nor did they have surveillance cameras which today can be found by the thousands in major Chinese cities. The way the case was solved was to catch Yu in the act. When leaflets were dropped, the police would rush to the scene and time how long it took for pieces of paper to fall to the ground. They would then flood the neighborhood to interview witnesses. This approach led to the identification of many suspects, none of which panned out.

Yu picked busy commercial streets to disburse pamphlets, such as Nanjing Road East. The old art-deco building was part

of the former Hardoon estate. Nanjing Road East was once known as Shanghai’s Fifth Avenue. Image source: Wikicommons

On the 108th day of the manhunt, Yu Rong was apprehended in the vicinity of his apartment building. Police noticed a nervous young man, sweating profusely. Yu was taken to his room where incriminating evidence was found (textbooks with torn pages and an ink slab and brush). The interrogation began but before long he was brought to a police station where the interrogation continued. Yu Rong eventually confessed.

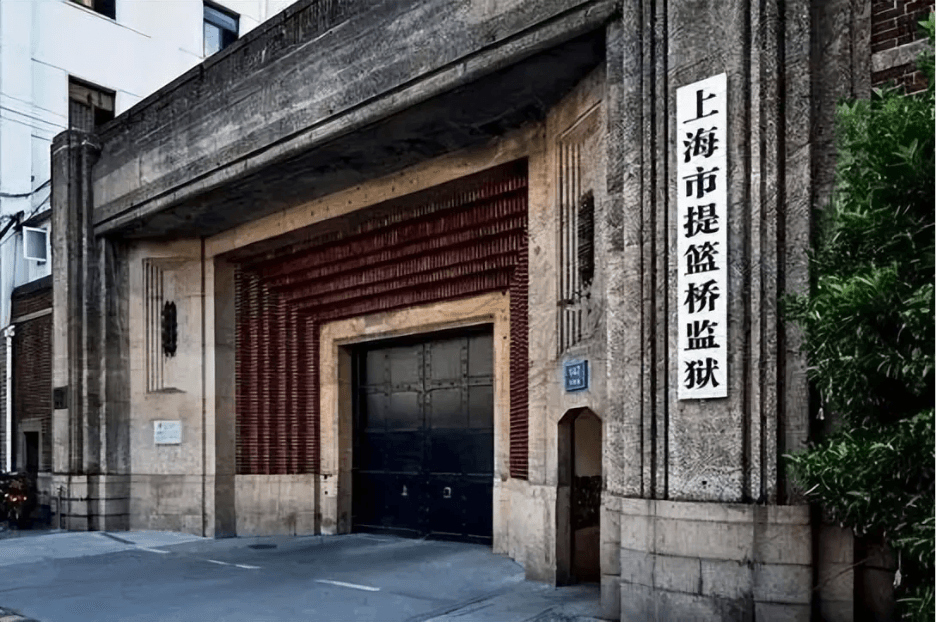

Tilanqiao

My first opportunity to raise Yu Rong’s case came in late 2000, the same year we found the issues of People’s Police in Hong Kong. I had flown to Beijing expecting to be granted a visit to Beijing Number Two Prison, but my request was denied. I was instead offered the chance to visit a prison in Shanghai, where the Ministry of Justice oversaw ten prisons. I returned to Hong Kong where we put together a list of more than 30 names of inmates in Shanghai facilities.

Tilanqiao Prison, at its former location. Part of the facility has been converted to the

Shanghai Prison History Museum. Image source: wenxiaobai.com

Only after my arrival in Shanghai on December 4, 2000, did I know that a visit to Tilanqiao would take place. After arriving, I asked the warden for information on the people on the list, including Yu Rong. (Other names on the list included Jiang Cunde, a labor organizer, and Li Junmin, an alleged Taiwan spy.) The warden, who was accompanied by officers of the Shanghai Prison Bureau, didn’t recognize Yu Rong’s name, but my request for information was noted and passed along to higher authorities.

Supreme People’s Court

When the attacks of September 11, 2001, took place, I was in Hong Kong. Flights out of Hong Kong were not cancelled, so I flew up to Beijing where I was able to meet with officials of several entities, including the Supreme People’s Court (SPC). I asked officers of the court to find information on Yu Rong.

Three months later, I returned to Beijing in the company of New York Times journalist Tina Rosenberg. Ms. Rosenberg was writing a story about my work for the publication’s Sunday Magazine (It would eventually be published as John Kamm’s Third Way in March 2002.) We secured a meeting with the SPC. One of the participants in the meeting was an official I had met at the September meeting. She had been unable to find any information on Yu Rong, leading Ms. Rosenberg to wonder if Yu Rong was still alive.

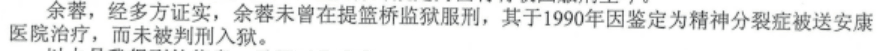

Ankang

I continued to make inquiries. In late 2005, I asked an interlocutor for help in getting information on three Shanghai detainees. In April 2006, I received a reply. Yu Yong had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and placed in an AnKang hospital. Ankang hospitals are psychiatric hospitals managed by public security bureaus. Detention in such facilities is open-ended and does not require the approval of a court.

Response received in a 2006 communication to Dui Hua. “According to multiple sources, Yu never served a sentence in Tilanqiao Prison. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1990 and was sent to receive treatment in an Ankang. He was not sentenced to imprisonment.

The foremost authority on psychiatric detention in China was the scholar and human rights activist Dr. Robin Munro, whose book China’s Psychiatric Inquisition, is the most comprehensive description of this cruel form of arbitrary detention. Dr. Munro used accounts in medical journals found in Mainland libraries, as well as interviews with experts and testimonies of those subjected to mistreatment in Ankang hospitals, and who lived to tell their stories.

China’s Psychiatric Inquisition, by Robin Munro. Image Source: wildy.com

Creative Dissent

Yu Rong found a way to express his opposition to government policies with a minimum chance of being discovered. Other dissidents have tried to do the same, while others are more brazen, unafraid of being discovered.

n a case similar to that of Yu Rong, a June 4 protester by the name of Li Huanming served a sentence for counterrevolution in Shaanxi Province after which he traveled south to Guangdong Province. He settled in Shenzhen, the booming city on the border with Hong Kong. There he planned to distribute thousands of photocopied leaflets by dropping them from tall buildings. He also placed stacks of the leaflets under bridges of the highway to Guangzhou, thinking that passing trucks would blow them into city streets and fields.

Another persecuted group, Falun Gong adherents, wrote messages on Chinese currency which it left lying about city parks. Dissident artists like Ai Weiwei and the Gao Brothers used artwork to express their views.

More recently, several instances of those dissatisfied with the state of life in China publicly denounced President Xi Jing Ping and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) or expressed support for public disobedience, such as the “white paper” movement. All were quickly seized by the police. The fates of many remain unknown.

The CCP and the government it controls have tried to suppress opposing views among the Chinese people. Results are mixed. Dissenters have held to the belief that, as Mao Zedong put it, “A single spark can start a prairie fire.”

| Ankang Ankang (安康), literally, “peace and health” are psychiatric treatment facilities under the direction of the Ministry of Public Security. They are not prison hospitals, as they are sometimes misidentified by Western media. Article 18 of the Criminal Law provides the substantive legal basis for compulsory psychiatric treatment of mentally ill offenders. Through a series of internal meeting minutes in the late 1980’s, the MPS quickly established and asserted its control over the administration of the facilities such as the Ankang hospitals. The system then expanded its functions to include forensic diagnostics in criminal investigations, under procedures further regulated by the Criminal Procedure Law, the People’s Police Law, mental health law, and public security regulations. Officially established in 1985, there are more than 24 such facilities in the country. These facilities are assigned by police to provide psychiatric evaluation in criminal cases, making the independence and neutrality of the evaluation problematic. Members of civil society often question the effectiveness of treatment carried out in Ankang, and the lack of transparency. |