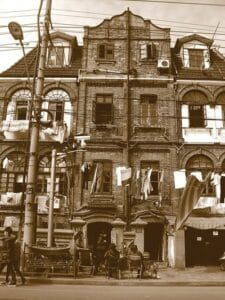

TIlanqiao Prison in Shanghai is one of the oldest operating prisons in the world. Constructed in 1903, occupied in 1906, it has gone by many names. Wood Road Gaol. Shanghai Prison. Oriental Bastille. Alcatraz of the Orient. City of the Doomed. It is where mothers in Shanghai threaten to send their children if they misbehave.

Thousands of inmates have entered Tilanqiao’s gates. Not all have survived. Some have gone mad. China’s longest serving political prisoner, labor leader Jiang Cunde, is incarcerated in Tilanqiao. He suffers from schizophrenia.

After NATO bombed China’s Belgrade embassy in 1999, I resumed my advocacy work as soon as I could. Part of that work involved visiting prisons. It was my practice to carry with me a list of prisoners believed to be in the facility I was visiting. I visited Beijing Prison in early 2000. Not long after this visit I began pushing for another visit to a prison in Beijing. I wanted to go to Beijing Number Two, where most political prisoners in the municipality are held, then as now.

In March 2000, plans were made for me to make a trip to Beijing in September, at which time I would visit a local prison. As soon as I arrived in Beijing in September I sensed problems. I was told that there would be no prison visit, and maybe no information on prisoners. The senior Ministry of Justice (MOJ) official who had agreed to my prison visit, as well as directors general of both the MOJ and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with whom I worked, were unavailable to see me. The reason given for why MOJ officials couldn’t meet me was that they had given blood earlier in the week. Phlebotomies are considered a serious medical procedure in China, I was told, requiring days of rest to recover.

I dug in my heals. A deal’s a deal. Officials were called back to work and we reached a compromise. I could visit a prison in Shanghai on my next trip to China, scheduled for December. The exact prison (at the time the Shanghai Prison Bureau administered 10 prisons, not counting two farms in Anhui and Jiangsu Provinces, respectively) and the timing of the visit would be up to the Shanghai Prison Bureau. The MOJ would send an officer to accompany me.

Flight to Shanghai

I flew to Shanghai from Hong Kong on December 3, still not knowing which prison I would visit. By then, the choice was down to two: Qing Pu, built in the 1990s to house, among others, foreign inmates, and Tilanqiao. I checked into the Hilton Hotel, opened in 1988 as the first foreign-owned hotel in China.

I arrived to find a message from my MOJ escort, Director Bai. We would visit Tilanqiao on December 5. Pick- up would be 2:00 PM. The next morning, December 6, we would fly to Beijing.

I had anticipated as much, so meetings were frontloaded prior to the prison visit. Over the next day and a half, I sat down with the American Consul General Hank Levine and his team, the Shanghai correspondents of The New York Times and the Associated Press, and two resident American businesspeople.

One topic kept coming up in my discussions with diplomats and journalists: the removal from office of the Minister of Justice, Gao Changli, on December 2, the day before I boarded the flight to Shanghai. At first, health issues were cited as the reason this man, who had built a formidable reputation as a legal reformer, had stepped down. Over the next 24 hours however, in time for my meetings, accusations emerged that Gao had engaged in large scale corruption and abuse of power.

There were darker rumors. Gao, it was said, had several mistresses and had overseen a scheme in which female prisoners were offered as sexual favors to well-heeled inmates and high officials, often after alcohol-infused dinners. Upon hearing these rumors, President Jiang Zemin was said to be livid. He angrily ordered the immediate removal of Gao Changli. Or so it was said at the time. The rumor was never confirmed. Gao emerged 10 years after his removal as an expert collector of calligraphy.

My lunch with The New York Times correspondent Craig Smith the day before I visited Tilanqiao set a dark mood for my stay in Shanghai. The journalist recently interviewed the brother of a man who had been executed for tax evasion. The brother, a well-to-do businessman, followed the execution van to the crematorium and when he could see and cradle the executed man, his deceased brother’s intestines fell out. His kidneys had been harvested. After giving wrenching interviews in his office, located in a high-rise tower overlooking the city, and a local pub, the man became fearful – he was being threatened by the police – and tried to walk back what he had told the journalist. (The story eventually appeared in The Times in March 2001.)

The car with my escort and an official from the Shanghai Prison Bureau, Mr. Zhao, showed up at the Hilton promptly at 2:00 PM. We headed for Tilanqiao.

As we sat in the car — it was a cold December day — I ventured to ask about the fall from power of Gao Changli. Ms. Bai was taken aback by my question. Yes, she said, he had stepped down for reasons of health; he had a bad back. She translated our conversation for Mr. Zhao. “You know about this?” he asked me. I replied it was much in the news. That would be the last time I heard from Mr. Zhao during the visit. He declined to give me his name card.

Tilanqiao Prison occupies a four-hectare plot in the middle of a largely residential neighborhood in Shanghai’s Hongkou district. It is a neighborhood steeped in history. The Jewish ghetto, established in the 1920s, sheltered Jews during the Second World War. Hongkou saved more Jews from the Nazis than any other metropolitan center in the world during the Holocaust, around 25,000 by several accounts. The Ohel Moshe Synagogue, meters from the gates of Tilanqiao Prison, can still be visited. Not far from Tilanqiao is the fabled Broadway Mansions, where I had stayed during my first trip to China in 1976.

The value of the plot of land that Tilanqiao occupies is enormous, especially given the sharp rise in land prices in recent years. For more than 10 years, there have been reports that it would be redeveloped as a mixed commercial residential complex, probably keeping the old British cell block as a tourist attraction. As of this writing, Tilanqiao remains very much in business as a prison, however. The municipal authorities have been unable to reach an agreement on the future of Tilanqiao with the prison bureau, which reports to the Ministry of Justice in Beijing.

Warden Li

We were met at the prison gate by Warden Li and his subordinates, all spit and polish in their fine dark blue uniforms. We entered the main courtyard. Overlooking the prison on two sides, cheek to jowl with its walls, were residential apartment blocks whose units offered a bird’s eye view of the main yard. “The broad masses people keep a close eye on our work,” the warden quipped.

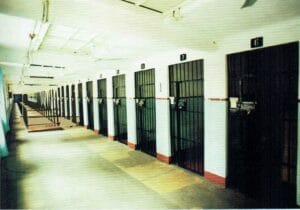

Our small group walked towards the pride of Tilanqiao, the old British cell block. The cell block was designed as a Panopticon. considered at the time of its construction to be the most scientific method of incarceration in the West, originally designed by the nineteenth-century British philosopher Jeremy Bentham as a wheel with the guard tower in the center, and spikes made up of lines of cells. A guard could monitor behavior without the inmates knowing they were being watched.

On the way to the old cellblock I was given basic information about the prison. There were around 4,000 inmates (up from 3,500 inmates in 1998) in 10 male cellblocks and one female cellblock. The prison housed convicts serving sentences of 10 or more years, including those serving sentences of death with two-year reprieve. (Those about to be executed are held in detention centers, not prisons.) This made Tilanqiao one of China’s premier maximum security prisons. It was also considered a model prison, one of the first to be opened to foreign visitors.

When I toured Tilanqiao in 2000, the old cell block was used as a museum and an exhibition space for artwork created by prisoners. One genre was models of buildings, including Tilanqiao itself, painstakingly pieced together from small pieces of wood. A model of the Panopticon itself took pride of place.

We headed for one of the male prisoner cell blocks, passing on the way the prison hospital, which served as the principal hospital for all 10 Shanghai prisons. The cell block was constructed in the 1930s, during the British period, and was made up of six floors. On the ground floor was the kitchen, where piping hot cauldrons of rice were being prepared for dinner. Bushels of fresh vegetables were on display.

We toured one of the floors of cells. There were no prisoners in the cells when I toured. Each cell had been designed for a single prisoner, but it was apparent that more than one prisoner was held in each. In addition to the wooden bunk, bedding was laid out on the floor. There was neither a lavatory nor a sink; a night soil pot could be seen in the corner. I was shown the key room. The cells, which opened onto a common area where prisoners could congregate and watch TV, were opened with keys still in use from the British era, big heavy steel devices. I was given a demonstration of how a cell was opened and locked.

I was taken to the workshop. Rows of prisoners, lined up in the hundreds, sat at benches cutting cloth to be sewed into prison uniforms. I was assured that none of the products were for export; export to the United States of goods made in Chinese prisons was a controversial issue at the time. I was invited to walk the middle line between the rows. I did so with some reluctance. In the hands of prisoners, several with expressions of deep anger in their eyes, were long pairs of sharp scissors.

An Artistic Troupe

We left the cell block and walked a few yards to a recently constructed prefab unit where, I was told, female artistic performers were held. There were 33 females in this “special unit.” I was led into the cell block. Women prisoners, behind a wire mesh, were doing laundry, hanging up their undergarments, and donning theatrical costumes. I wrote in my notebook, “The women were clearly chosen for their appearance.” They met my eyes with defiant looks. I had seen women behind glass windows and even in cages in Southeast Asia, but I never imagined I’d see something like this in China.

We left the women’s cellblock and headed for the theatrical performance at the prison’s auditorium. Our small party made up the entire audience. A special program was laid on by “The Xin-An Art Ensemble of Shanghai Tilanqiao Prison.” In all there were more than a dozen female performers and three male performers dressed up in traditional Han, Mongolian, Tibetan, and Uyghur garb. For an hour, we were treated to renditions of Leonard Bernstein’s Magnificent Seven, a tenor solo from an Italian opera, the theme from the movie Love Story and an assortment of ethnic song and dance routines.

The last stop was the warden’s office, which was housed in the headquarters of the Shanghai Prison Bureau on the prison grounds. It was a squat red brick building constructed much like municipal administrative buildings throughout the British empire in the 1920s and 30s.

Political Prisoners in Tilanqiao

Warden Li and his colleagues asked about my impressions of Tilanqiao. I replied that I was impressed by how clean the prison looked. It certainly appeared that there was plentiful food. The staff looked to me to be professional. It was clear however that the prison was extremely overcrowded. I said that I was uncomfortable at times in both the male and female wards. I recommended that foreign guests not be allowed to get too close to inmates holding sharp scissors.

Warden Li thanked me for my comments and asked if I had any questions before we had dinner at a hairy crab restaurant. I said yes, I wanted to talk about people who might be imprisoned at Tilanqiao, and hear from the warden whatever information he could give me on them. Warden Li became somewhat uneasy at this, even more so when I pulled out my prisoner list.

I said I wanted to learn about someone on my prisoner lists who had been sent to Tilanqiao to serve a two-year sentence, Mr. Lin Hai, who had been released six months early and gone to the United States. Mr. Lin was said to be China’s first Internet dissident.

I remarked that I thought that only prisoners sentenced to 10 years or longer were housed at the prison. Warden Li replied that all Shanghai counterrevolutionaries were housed at Tilanqiao as part of a policy implemented in 1986 to segregate this special group of prisoners from the general population. Since then the number of counterrevolutionaries (and, after 1997, prisoners convicted of endangering state security) had been halved. It now stood at 17, half of whom were Taiwanese spies. I felt that segregating political prisoners from the general population was an enlightened policy; in some provinces, political prisoners in the general population are bullied by other prisoners, especially those serving time for violent crime. In fact, after his release, Lin revealed that he had not been mistreated, and had not been forced to do manual labor. He complained, however, about overcrowding, saying that he shared his small cell with one or at times two other prisoners.

Since 1986, sentence reductions for political prisoners had increased, but the rate of reduction was well below that for ordinary prisoners, Warden Li acknowledged.

I wondered if Warden Li was familiar with the name Yu Rong, a young man who had thrown 1,400 counterrevolutionary leaflets from the tops of downtown Shanghai buildings in 1990, a case that then-mayor Zhu Rongji dubbed the biggest case of counterrevolutionary incitement and propaganda in the city’s history. Warden Li was not familiar with the name. (In 2006 I learned that Yu Rong had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and was incarcerated in a psychiatric detention center, also known as Ankang.)

I asked about Tao Shanben, sentenced to life in prison for being a follower of the Gang of Four. Warden Li said there were no more Gang of Four elements in the Shanghai prison system.

Warden Li recognized the names Yao Kaiwen and Gao Xiaoliang as convicts who had tried to set up a counterrevolutionary group. Beyond that, he declined to say more. According to my notes, Yao, a school teacher, and Gao, a worker, had been detained in May 1993 for establishing “The Mainland Headquarters of the Democratic China Front.” They were subsequently sentenced to 10 years and nine years in prison, respectively. Gao received a sentence reduction after my visit, and was released in late 2001. Yao served his full term and was released in May 2003.

Li Junmin in The City of the Doomed

Sensing that the time for questions was running out, I moved on to my last two prisoners, Taiwanese spies Zhou Guogui and Li Junmin. I had received information on them from the MOJ in March 2000 at which time both were serving sentences in Tilanqiao.

Zhou was an elderly Hong Kong doctor who had been sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment in 1986 for spying for Taiwan. Because he suffered from a heart condition and high blood pressure, he was released on medical parole a few months before my visit.

Li Junmin was the most famous counterrevolutionary prisoner in Shanghai at the time. A Taiwanese intelligence officer, he was sentenced to life in prison for espionage in May 1982 and sent to Tilanqiao. While in Tilanqiao, he managed to send letters detailing conditions in the detention center in which he had been held prior to being sent to Tilanqiao. He sent the letters through prisoners who were about to be released. He also carried out “counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement” among other prisoners – “viciously attacking the Communist Party and seeking to overthrow China’s socialist system.”

Li was tried again for his new crimes, and the Shanghai Intermediate People’s Court sentenced him to death in December 1983. The Shanghai High People’s Court upheld the verdict and sent the case for final review to the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) in Beijing. Following a decision made during the Strike Hard Campaign of the summer of 1983, death sentences could be carried out after the provincial high court had rejected an appeal, with an important exception: death sentences for counterrevolution had to be reviewed and approved by the SPC in Beijing.

The SPC overturned the death sentence and passed a sentence of death with two-year reprieve in February 1984. In June 1986, this sentence was commuted to life in prison. Li’s life sentence was reduced to 18 years with seven years’ deprivation of political rights in June 1994. At the time of my visit to Tilanqiao, Li was scheduled to be released on December 20, 2012.

In contrast to his responses on other prisoners, Warden Li became quite animated when I mentioned Li Junmin’s name. In language reminiscent of how Democracy Wall prisoner Wei Jingsheng was described to me by MOJ officials in 1992, Li Junmin was “defiant, and resists reform. For a long time, he had nothing good to say about the Chinese government, but now he has acknowledged that recent developments might be good for the Chinese people,” said Warden Li. “He now wishes both China and Taiwan well.” Warden Li expressed the hope that, one day, there would be no prisoners serving sentences for counterrevolution or endangering state security in his prison, but for the foreseeable future, Li Junmin would stay in Tilanqiao.

A few months after my visit Li Junmin was given an eight-month sentence reduction. In 2003 he was granted a 14-month sentence reduction and this was followed in 2004 by a 12-month reduction. His sentence was commuted in December 2006. He returned to Taiwan to be greeted by his wife, who had never given up on Li Junmin despite being told by the Taiwan government that he was dead, and the son he had never known. Li Junmin had survived the City of the Doomed.