<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

Acting on a recommendation by Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy Human Rights and Labor Richard Shifter, I began submitting prisoner lists to the Chinese government in 1991. In January 1995 I gathered all the responses on prisoners that I received from the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) and the State Council Information Office (SCIO) in 1993 and 1994, 50 in all, and sent a booklet containing the information to senior officials of the MOJ and the SCIO in Beijing.

I flew from Hong Kong to Beijing on Wednesday, February 15, and immediately went to the Jianguo Hotel upon arrival. The next day I met with SCIO Minister Zeng Jianhui, and Liang Gang, Director of the MOJ’s Prison Administration Bureau and his colleague Zhang Jinsheng. (Zeng, now 93 years old, had served as Vice President of the New China News Agency when he was picked to head the SCIO in 1990. He went on to chair the National People’s Congress Foreign Affairs Committee.) We met at the offices of the SCIO, a drab structure next to the Asian Games Village, a 30-minute drive from the Jianguo Hotel.

I started the conversation by asking Minister Zeng whether he had read the recently released human rights report on China released by the Department of State. He replied that he had read it and felt that it was negative and full of mistakes. I pointed out that the report made favorable mention of my cooperation with the Chinese government on prisoner information. Minister Zeng called that mention one of the few positive things in the report.

I then asked what he thought of the compilation of prisoner information that I had faxed to him a few weeks before. He replied that he had received it. “What do you think?” I asked. “You have accurately reported what you were told.” I then asked if we should continue our cooperation, and the minister replied “Of course.”

I took a chance, apologizing for causing so much work for the MOJ. “I suggest I limit my inquiries to 100 names in 1995, 25 a quarter.” Minister Zeng checked with the MOJ officials, and they nodded agreement. “Great,” I said, and extended my hand for a handshake. All present shook hands. Information on prisoners would be provided during in-person meetings or by fax.

I then handed over my first list of 25 names, singling out Yang Lianzi, Zhao Fengping, and Jigme Sangpo for special attention. Yang was an itinerant troubadour who entertained crowds at Tiananmen Square with protest songs and poems. Zhao founded the Northeast China Autonomous People’s Republic, a counterrevolutionary organization. Jigme Sangpo had been a schoolteacher in Lhasa who was now serving a long sentence for counterrevolution.

After I left the meeting I was hosted to a dinner by my host, the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade. The conversation centered around prospects for Most Favored Nation (MFN) renewal in 1995.

I returned to Beijing on April 24, 1995 and met with the SCIO Director of the Domestic Information Bureau Zhou Changnian and the MOJ’s Liang Gang, director of the Prison Administration Bureau. We met at the SCIO office on April 26. As soon as we sat down, Liang Gang handed over responses to 19 of the names on my first list of 25 names. He explained the difficulties in obtaining information on prisoners but said the MOJ was committed to providing information to the best of its ability. I handed over my second list of 25 names. I was informed that the SCIO had established a small human rights unit within the office.

As I had done at the February meeting, I focused on several prisoners including Hong Kong journalist Xi Yang in prison for trafficking in state secrets, Tibetan prisoner Tenpa Wangdrag who had been severely punished for attempting to hand over a letter to American Ambassador Jim Lilley when he visited Drapchi Prison, and Ahmet Jan, a young Uyghur who had been given a long prison sentence for establishing a reactionary organization. After the meeting, I visited bookstores where I found the names and basic information on several previously unknown prisoners. Their names were added to my lists.

Not long after this April visit, the MOJ sent out a directive to prisons under its control requiring them to report on a regular basis the situations of political and religious prisoners.

Taiwan Strait Crisis

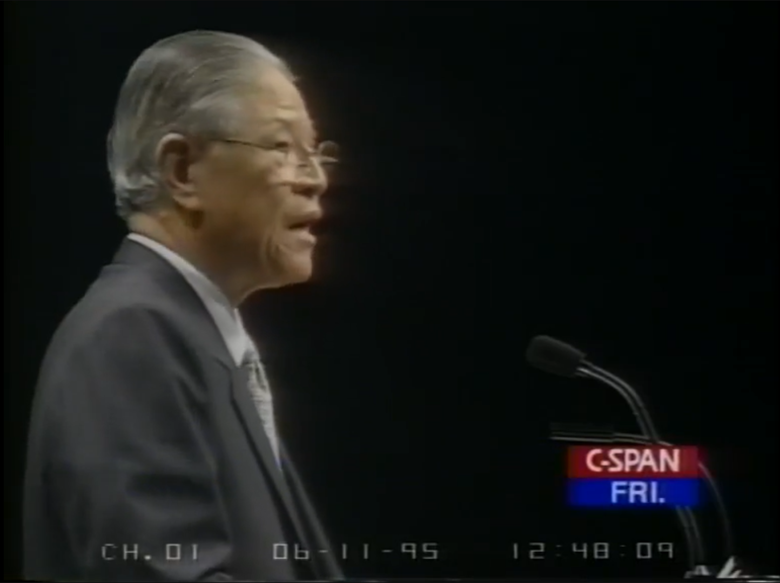

In 1994, Taiwan President Lee Teng-hui transited Honolulu on his way to South America, where a number of countries maintained diplomatic relations with the Republic of China. President Bill Clinton’s State Department refused to grant Lee a visa, so he spent the evening on his plane, on the tarmac.

A year later, Lee Teng-hui was invited to speak at his alma mater, Cornell University. Lee accepted the invitation. Chinese foreign minister Qian Qichen claimed that Secretary of State Warren Christopher assured him in April 1995 that Lee would not be granted a visa. Whatever the truth, Congress stepped in and passed a concurrent resolution. Even though a concurrent resolution, as opposed to a joint resolution, need not be signed by the president, the State Department relented and issued the visa. Lee visited Cornell June 9-10, 1995.

Beijing was furious and accused the United States of violating the “One China” principle and “ruining US-China relations.” In July and August, the Chinese military fired barrages of missiles into the waters off Taiwan, mobilized troops in Fujian Province, and conducted amphibious landing exercises.

Bill Clinton’s administration responded by bolstering the US naval presence in the area around Taiwan. Two aircraft battle groups were dispatched, and one of them sailed through the Taiwan Strait. China stopped the missile firings, and it appeared that the Chinese military had backed down, but the relaxation of tensions proved short-lived. In March 1996, just before Taiwan’s presidential election, the firings resumed. Once again, the United States dispatched a carrier battle group to the region. US-China relations had entered a period of crisis that was to last through the November 1996 US presidential election.

My cooperation with the SCIO and MOJ stalled. For my part, I sent my third and fourth quarter lists to the MOJ in August and December 1995. As I told Chinese officials at the time, I had lived up to my side of the agreement.

Stalemate

I traveled to Beijing in February and May 1996, meeting with the SCIO and the MOJ on both trips. I was told by both organizations, and by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), that it had been decided to suspend providing information to me “for the time being,” due to tensions in US-China relations.

In addition to the fallout from the Taiwan Strait crisis, Beijing was increasingly concerned about the likelihood that the United States would put forward a China resolution at the Human Rights Commission in Geneva. If that happened, I was told by a senior official in the MFA, US-China relations would enter an “ice age.” I was also told that the best way to repair relations would be for President Clinton to invite Chinese President Jiang Zemin to make a state visit to the United States.

On June 2, 1996, I arrived in Washington to present a list of recommendations for US policy towards China now that MFN had been extended without human rights conditions. My recommendations included establishing a consulate in Lhasa, setting up a prisoner registry, and putting together a bipartisan, bicameral commission on human rights in China. I met with members of the Clinton administration and Congress to introduce my recommendations and to ask a favor: would they be willing to write letters urging Beijing to follow through on commitments to provide information, as promised, on prisoners about whom I had asked in 1995?

Prior to my visit to Washington in June, I went to Beijing in May and managed to hand over a new list of 25 names to MOJ, thus bringing to 100 the number of outstanding inquiries. My thinking was to keep the pressure on while I was waiting for responses to the remaining 75 names on the 1995 lists. It was a tactic I would use again before Jiang Zemin’s state visit to the United States in October 1997.

Starting with my testimonies on MFN in 1990, I had met with scores of members of the House of Representatives, Senators, and senior staff in Washington, San Francisco, and Hong Kong, and had formed strong friendships with several. My visits to Washington were facilitated by Hal Furman, a lawyer who had served in the Reagan administration and who had lost a narrow race for Senator from Nevada in 1994.

The plan I worked out with Mr. Furman was to ask members of both chambers, from both parties, and with different China positions to write letters addressed to me for forwarding, or directly to Chinese officials including the Chinese ambassador in Washington. On the early June 1996 trip, I asked Senators John Kerry (D-MA), Craig Thomas (R-WY) and congressmen Matt Salmon (R-AR) and Ed Royce (R-CA) to write letters. They all agreed to do so.

Over the next two years, 20 letters were written from Senators and Congresspeople to me, Chinese ambassador Li Daoyu, Chinese President Jiang Zemin, Chinese Premier Li Peng, and Minister of Justice Xiao Yang. I also received a verbal commitment to help from House Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-Georgia) and, after a somewhat contentious session, from Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-California). On a visit to Beijing, Congressman Ed Royce (R-California) – he went on to become Chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee – managed to hand one of my lists to a startled Premier Li Peng.

The first letter came from Senator John Kerry. He had visited San Francisco on March 31, 1996, and together we had met with the Chinese consul general. Minister Song Zengshou. One of the topics the senator raised was the violation of American company intellectual property rights (IPR) by Chinese state-owned enterprises. The consul general claimed that the Chinese government was not able to track IPR violations by Chinese firms. Senator Kerry scoffed: “You can track citizens who voice dissenting views, but you can’t track companies that violate IPR?”

In his letter to me on June 11, 1996, Senator Kerry said that the “noteworthy success” of my dialogue with the MOJ “testifies to the wisdom of pursuing engagement with, not containment of, China.” He asked that as soon as I had received responses to my lists, I let him know so that he could invite me to Washington “to brief some of my skeptical colleagues on the value of dialog on human rights with the Chinese government.” He dangled the possibility of my testifying to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on the results of my work in China.

Two days after the Senator Kerry letter, Senator Craig Thomas (R-Wyoming), chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee’s Asian and Pacific Affairs Subcommittee, sent a letter to Chinese ambassador Li Daoyu. He told Ambassador Li that he thought my cooperation with the MOJ was significant and valuable and urged him to contact MOJ minister Xiao Yang and SCIO deputy director Ma Yuzhen to resume the Prisoner Information Project. Like Senator Kerry, he said it would be desirable for me to come to Washington to brief colleagues.

Two months went by. The letters from Senators Kerry and Thomas failed to get the desired results, so I turned to Congressman Chris Smith (D-New Jersey), chairman of the House of Representatives Subcommittee on Human Rights and a strong critic of China’s human rights record. I had met Congressman Smith at my first testimony on MFN in May 1990, and he and I had become friends (we both grew up on the New Jersey shore, so we were both “clam diggers”). In his letter, addressed to me and dated September 17, 1996, he made the point that for dialogue to be effective, “the question of trustworthiness is critical.” He too invited me to come to Washington to share with colleagues whatever information on prisoners I obtained “as we continue to assess US-China relations.”

The three letters appear to have had an impact. On October 15, 1996, the Director of the MOJ’s Prison Administration Bureau, sent me a letter stating that “the Chinese side does not have the duty to provide the American side with the information on the seventy-five inmates you mentioned.” I immediately replied, saying that I agreed that the Chinese government is not obligated to provide information about its prisoners to foreign governments, but stressing that this was a situation involving a private individual to whom the Chinese government had made a promise. My letter went unanswered. After waiting a few months, I resumed pressing members of Congress to write letters to the Chinese government.

On February 5, 1997, Congressman Lee Hamilton, Ranking Democratic member of the House International Relations Committee, wrote to Chinese Ambassador Li Daoyu expressing support for my work and asking him to urge the MOJ to provide the information that had been promised to me two years before. In quick succession, letters were sent by Congressman Matt Salmon (R-Arizona), who had studied Mandarin as a Mormon missionary in Taiwan, to Ambassador Li Daoyu (March 10, 1997) urging China to honor its commitment to me; Congressman Ed Royce (R-California) to Chinese premier Li Peng (March 21, 1997) pointing out the importance of honoring commitments; and Senators Max Baucus (D-Montana) to Ambassador Li (April 14, 1997), Paul Wellstone (D-Minnesota), and Congressman Doug Bereuter (R-Nebraska) to Ambassador Li, all urging the Chinese government to renew cooperation.

In June 1997, President Bill Clinton gave me the first Global Practices Award for my work on behalf of lesser-known political prisoners in China.

In August 1997, National Security Advisor Sandy Berger traveled to Beijing for discussions with Chinese President Jiang Zemin about a possible state visit to the United States in October 1997. After Berger’s return to the United States, the Department of State announced that President Bill Clinton would host Jiang on a nine-day visit in late October. A summit between the two leaders would take place on October 29, 1997.

Prior to Jiang’s arrival in the United States, I sent the MOJ two new lists: one a “national list” with 37 names from provinces all of China, and one a list of 24 counterrevolutionaries and hooligans in Shandong Province, where leaders of the June 1989 protests had received some of the longest prison sentences in China. Also prior to the October summit Senator Hatch (R-Utah) visited China and intervened on my behalf with President Jiang Zemin and Minister of Justice Xiao Yang, urging them, in private meetings, to resume providing the information promised to me.

Talks between the two governments began on a list of “deliverables,” things that the two countries wanted to see come out of the Clinton-Jiang summit. One of the American deliverables was the resumption of my “prisoner information project.” A joint statement issued at the end of the summit affirmed both sides’ commitment to holding human rights dialogues involving both governmental and non-governmental organizations. A side document referenced resumption of the prisoner information project. (Mine was the only name in the joint statement documents. Mention of my name in Chinese, Kang Yuan, prompted hilarity on the Chinese side: Kang Yuan is a homonym of the name of a popular biscuit in China).

Unfortunately, information did not begin to flow, necessitating another barrage of letters from members of Congress including Congressman Don Manzullo (R-Illinois) to Jiang Zemin (Manzullo attached one of my lists of religious prisoners to his letter), Senator Orrin Hatch (expressing disappointment that the promised information had yet to be provided), and Senator Jesse Helms, perhaps the fiercest critic of “Red China” in the Senate.

All the while I was getting lawmakers to write letters, senior administration officials including Secretary of State Madeline Albright and National Security Advisors Tony Lake and Sandy Berger were raising the Chinese side’s failure to honor their commitments with senior Chinese officials, including Foreign Minister Tang Jiaxuan, even after President Jiang’s promise that it would do so. The American embassy in Beijing also weighed in, pressing the Ministry of Justice to resume providing information. President Clinton exchanged letters with Senator Hatch in which the president expressed strong support for my efforts. I was authorized to provide the letters to the Chinese government.

In February 1998 I traveled to Atlanta to attend a conference with former President Jimmy Carter. On February 13, I received a phone call from Bai Ping, Deputy Director Bai Ping of the MOJ’s Foreign Affairs Bureau, advising me that I would be sent information on prisoners “in a few days.” As promised, I received the information – a partial installment on the list of 100 – a week later. I advised Senator Hatch, who commended me on this achievement, and other members of the House of Representatives and Senate who had supported me.

By the time Dui Hua was established in April 1999, the MOJ had fulfilled its 1995 commitment to provide information on 100 prisoners, “to the best of its ability.” The last installment was provided June 22, 1998, the eve of President Clinton’s state visit to China. Bolstering my claim, made in Congressional testimony in September 2006, that asking about prisoners tripled the chance of clemency, a majority of prisoners on my 1995, 1996, and 1997 lists had been granted early release from prison, while others had benefited from better treatment.

After the resumption of the prisoner information project, members of Congress and the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations continued to write letters to Chinese officials supporting my efforts to win the release of counterrevolutionaries and reduce use of the death penalty. Some letters asked for my help in assisting constituent’s family members incarcerated in China. Some letters, including one sent to Religious Affairs Bureau chief Ye Xiaowen by Congressman Joe Pitts, were sent with prisoner lists.

In all, 60 letters were written from 1996 to 2007. Letters were written by members of the Senate and House of Representatives including House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-California), House Majority Whip Tom Delay, Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee William Roth (R-Delaware), Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle (D-South Dakota), Senator John McCain (R-Arizona), Senator Joe Leiberman (D-Connecticut), Senator Sam Brownback (R-Kansas), Senator Tim Hutchinson (R-Arkansas), Pete Sessions (R-Texas), Phil Crane (R-Illinois), Howard Berman (D-California), and Jim Leach (R-Iowa). The last letter, dated June 5, 2007, was written to me by Senator Byron Dorgan (D-North Dakota) following a discussion we had in Rome.

The experience of having to fight for MFN renewal taught Beijing the importance of Congress in making China policy. After China gained entry to the World Trade Organization in December 2001, it gradually came around to the view that Congress was less and less important in formulating China policy, even though, in 2020, more than 300 bills and resolutions touching on China’s “core interests” in Hong Kong, Tibet, Taiwan, and Xinjiang were debated in Congress, and several were passed by both chambers with veto-proof majorities. Today, letters from congresspeople and senators to the Chinese government are often ignored and almost never acted on. I took advantage of a special moment in the history of US-China relations to use Congress to help political prisoners in China.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.