<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

Download this story as PDF

Listen to our podcast series

When it came to media coverage of the 1989 protests in China, the protests in Beijing received the most attention. This was largely because of the presence of international media outlets in China’s capital. Their ranks were bolstered by journalists from around the world who were in Beijing for a Sino-Soviet Summit that featured Mikhail Gorbachev.

Leaders of the June 4 protests in Beijing became household names. But Beijing was by no means the only city that experienced mass protests. According to one estimate, as many as 300 medium and large cities across China experienced large protests. Any city with a college or university was the site of protests.

I was in Zhuhai, Guangdong Province, one of the 300 cities where protests took place, when the killings in Tiananmen Square happened. Sitting with a group of Chinese officials, we watched events unfold on a Hong Kong television network. I was horrified by what I saw, as was one of the Chinese officials. (The others were silent, with the exception of a party member who admonished the official who expressed anger at what was broadcast from Beijing.) The next day, as my colleagues and I drove back to Macau, we passed signs of the unrest that had taken place the night before, with placards strewn across the roads and sidewalks, and graffiti condemning China’s leaders. In Macau we passed long lines of people withdrawing money from the Bank of China.

Bengbu, a city in northern Anhui Province with nearly a million urban residents at the time, was among the locations where protests erupted. This important transportation and trade hub, home to a medical school, saw tens of thousands of students and citizens march in response to the bloodshed in Beijing. As I was to discover, the protests were organized and led by a charismatic graduate of Tsinghua University–Zhang Lin (张林).

The Green Bible and Zhang Lin

In February 1994, Human Rights Watch published Detained in China and Tibet (DICAT). Robin Munro, a co-author, came to my office in Hong Kong to deliver an inscribed copy of the book. Because DICAT had a green stripe that adorned the front and back covers, my inner circle dubbed it “The Green Bible.” I used DICAT to populate my prisoner lists submitted to the Chinese government throughout the 1990s and well into the 2000s.

DICAT is a 632-page tome that documents the treatment of 1,700 hundred political prisoners in China, including hundreds detained in the aftermath of the spring 1989 protests in Beijing and other cities. One section in particular drew my attention: “Status Unclear.”

The first entry was for an activist from Anhui Province by the name of Zhang Lin, the head of the Bengbu Autonomous Student Union. The account of Zhang’s activities in Bengbu in May and June 1989 was based on a broadcast program on Anhui Radio that took place on June 14, 1989.

Not long afterward, I went to the Universities Service Centre (USC) in Hong Kong which had an extensive collection of provincial newspapers that included the Anhui Daily. I scoured the editions printed in May and June 1989 and found two articles that mentioned Zhang Lin. One article, published on June 15, 1989, ran with a headline “Zhang Lin Detained According to Law by the Public Security Bureau.” Another article concerned Zhao Fengrong (赵凤荣), an elderly farmer who had requested pamphlets and asked for advice from Zhang Lin.

This method of cross-referencing DICAT’s transcribed radio broadcasts with contemporary newspaper articles proved invaluable in my work identifying and inquiring about political prisoners in China. I used this technique in other cases as well, such as uncovering the correct spelling of three leading members of the Preparatory Committee for the Northeast China People’s Autonomous Republic, a shadowy group that operated in Jilin Province in the early 1980s.

In writing this John Kamm Remembers about Zhang Lin, I interviewed and asked him if he remembered Zhao Fengrong. He replied that he did; in fact, as the leader of the protests, Zhang had interacted with hundreds of people providing them with support and guidance.

Unbeknownst to the outside world at the time of my initial research in 1994, Zhang had actually been released in 1991 after serving his sentence over his role in the 1989 protests. By the time I came across his name in DICAT, Zhang had been sent to a reeducation through labor (RTL) camp for hooliganism in 1994, when he tried to organize independent labor unions in Anhui.

Portrait of Zhang Lin’s Activism

Put together, the Anhui Radio broadcast and the Anhui Daily articles found at Hong Kong’s USC, paint a picture of Zhang Lin’s activism during April, May, and June 1989. He comes across as a dedicated and innovative leader with strong organizational and oratory skills. He inspired others to protest the events that unfolded in Beijing in the spring of 1989.

An avid listener to Voice of America broadcasts, Zhang established the Bengpu Student Autonomous Union on May 19, 1989, and subsequently set up two political parties; he organized a large protest march, blocked roads, staged sit-ins, and led a hunger strike outside the city’s party headquarters. He encouraged students to travel to Beijing to take part in the Tiananmen protests and he formed a “Dare-to-Die Corps” against Bengpu’s party committee and government. The purpose of these corps, formed in many cities, was to block roads and otherwise disrupt traffic, in an attempt to delay armed police from entering the cities. Zhang himself traveled to Beijing in an unsuccessful attempt to meet Fang Lizhi, the dissident astrophysicist. He established a Democracy Center and Human Rights Office at Bengbu Medical School. All of these activities were non-violent.

The June 1989 protests were not the first time Zhang Lin had caught the attention of the Chinese police. In 1980, while a student, he traveled to Beijing to copy posters on Xidan’s Democracy Wall, and to purchase books and magazines on democracy. He shared them with fellow students at school who promptly informed on him. He was designated as a member of “targeted people (zhongdian renkou 重点人口),” a group including politically unreliable people subjected to strict surveillance.

First imprisonment

After he was detained and arrested in 1989, Zhang Lin was put in the Bengbu Detention Center, where he was mistreated. He would have been sentenced to a longer period behind bars, or even sentenced to death for allegedly having committed five different crimes, but he negotiated a deal with the authorities. In exchange for not appealing, he received a two-year prison sentence with the understanding that he would be granted a three-month early release. He served 21 months at the detention center until he was granted medical parole. While inside, Zhang learned of the visit of United States (US) National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft to Beijing in July 1989. Thereafter, the harsh interrogations ended.

Thanks to a sympathetic party leader, protests in Anhui were dealt with a relatively light hand. Aside from Zhang Lin, one other protester was sentenced to prison: Wei Hui (魏辉). He was sentenced to one year in prison and became a businessman after release. Treatment of June 4 protesters varied widely from province to province. In Shandong Province, for example, protesters were treated harshly – at least two were sentenced to 18 years in prison–while in Guangdong, like Anhui, protesters received relatively light sentences.

Hitting a Roadblock

By the end of 1994 I had pulled together all available information on Zhang Lin. I moved to the next stage of advocacy: compiling prisoner lists for submission to the Chinese government. I resolved to do so in 1995.

In February 1995, I flew to Beijing for a meeting with the State Council Information Office and the Ministry of Justice (MOJ). I suggested that for the year, I would submit quarterly lists of 25 names each. They agreed, whereupon I handed over my first list of 25 names. I returned to Beijing in April and was given a response. Then I handed over the next list. My plan was to add Zhang Lin’s name in the third quarter. (Eventually, I resorted to sending this list by fax.)

But in May of the same year, my advocacy effort on behalf of Chinese prisoners came to an abrupt halt. On May 22, the US Department of State announced that a visa would be granted to Taiwan president Lee Teng-hui so that he could attend his reunion at Cornell University. Beijing was furious, threatened retaliation, and began firing missiles over and near Taiwan. The US sent two carrier groups to the sea around the island. US-China relations went into a deep freeze.

On May 29, I returned to Beijing. I was questioned by immigration officers and ordered to wait in a small room before being cleared. When they were told to let me through, an officer threw my passport at me.

At the hotel, I found that my reservation had been cancelled. I was under surveillance the entire time in Beijing and unable to meet with anyone other than officials of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who lectured me on the bad behavior and broken promises of the Clinton administration.

It wasn’t until early 1998 that I received a response on Zhang Lin from the MOJ. Soon after he was released from a labor camp, completing his second imprisonment.

Founding a Political Party in New York, Illegally Crossing the Border to China

In early 1998, Zhang Lin traveled to the US. There he met with prominent activist and broadcast journalist Ann Noonan (now Executive Director of the Committee for US International Broadcasting) and veteran pro-democracy leader Wang Bingzhang, a Chinese citizen and US permanent resident. Together, Wang and Zhang established the China Democracy Justice Party, a forerunner of the China Democracy Party.

In October, Zhang attempted to return to China via Hong Kong. He rented a boat in the former British colony and tried to enter Guangdong Province, but he was apprehended in Guangzhou where he was detained and subsequently arrested for illegal border crossing, a crime used to imprison Protestant missionaries who sought to enter China to proselytize. Many have suffered this fate in recent years.

Zhang was sentenced to three years of RTL which he served in a labor camp in Guangzhou. In our conversation, he recalled that particular experience to be the worst out of all his incarcerations.

Then, in 2004, Zhang joined with Yang Tongyan (杨同彦, aka Yang Tianshui 杨天水) to establish the Anhui-Jiangsu chapter of the CDP. Zhang’s fate mirrored his previous experiences: in 2005, he was incarcerated for the fourth time, charged with inciting subversion. The sentence carried five years imprisonment with four years deprivation of political rights.

Zhang’s fellow activists suffered similar outcomes. Wang disappeared while traveling in Vietnam and was convicted of espionage and for organizing a terrorist organization in 2003. He is now serving a life sentence in Shaoguan Prison in Guangdong Province. Yang was charged with subversion in 2005. He served three prison terms, a total of 22 years in Chinese prisons and died of cancer shortly after he was released on medical parole in 2017.

Exploring different channels

In 1999, after his arrest for illegal border crossing, I switched tactics and began asking about Zhang Lin through a different interlocutor, a party-controlled policy research association. In 2006, following his arrest for inciting subversion, I switched tactics again, filing inquiries through governments including the US, the European Union, and the United Kingdom. Altogether Dui Hua submitted 10 lists with Zhang Lin’s name and received written responses to five of them.

Zhang Lin’s case was taken up by four United Nations (UN) Special Procedures on three occasions – in 2005, 2011, and 2014. (Dui Hua was granted Special Consultative Status with ECOSOC, the committee that oversees the UNs’ human rights mechanisms, in 2005.) The Special Procedures brought to the Chinese government’s attention “the alleged detention and conviction of Mr. Zhang Lin and the harassment of family members.” Aside from responding to the first UN inquiry in 2005, Beijing took no other action and declined to respond to the 2011 and 2014 requests.

Anni and Ruli Zhang

The 2014 UN inquiry was related to events in February 2013, when Zhang Lin and his youngest daughter Anni moved to be with his eldest daughter Ruli who was in college in Hefei, capital of Anhui Province.

On February 27, Zhang Lin was taken into custody by the local police, and, on the same day, Anni was taken from the school where she had recently been enrolled by guobao, the national security police operating under the public security bureau. Both Zhang Lin and Anni were taken back to Bengpu where Anni was placed in a police station. She was held there for 20 hours unaccompanied by female officers, in violation of the recently passed Criminal Procedure Law. The next day, Anni was released. Both she and her father stayed in Bengbu.

On April 7, lawyers Xu Zhiyong, Zhao Yonglin, Tang Jianhao, and others arrived in Bengbu to start a coordinated protest. The next day, Zhang Lin, Anni, and his supporters returned to Hefei. Another attempt to enroll Anni in school failed, prompting a 24-hour hunger strike by Xu Zhiyong and others outside the school. Anni, assisted by Zhang Lin’s supporters, penned an open letter to Peng Liyuan, wife of Xi Jinping, pleading for her assistance in enrolling at school.

Police moved in and cleared the protesters, several of whom were taken into custody. Some were given short sentences of administrative detention while others were sent back to their homes. Zhang and Anni were sent back to Bengbu, where Zhang was detained in July for “gathering a crowd to disrupt traffic and public order.” He was tried and sentenced a year later to three and a half years in prison, his fifth imprisonment.

Fearing for the safety of Zhang’s children, supporters in and out of the country worked to bring them abroad. In September 2013, Yao Cheng, a friend of Zhang Lin’s, took Ruli, Anni, and their mother to the US consulate in Shanghai to apply for a visa so that the children could study in the US. On September 3, 2013, Yao Cheng was detained and subsequently sentenced, in December 2014, to one year and 10 months in prison for gathering a crowd to disrupt public order. He was released in June 2015.

Around the same time, activists in the US also went to work. Ann Noonan introduced Reggie Littlejohn, a fierce advocate for the rights of women and children in China, to me. Together we coordinated frequent exchanges with the Department of State in Washington DC, the embassy in Beijing, and the Shanghai consulate. Being informed, the consulate was prepared for the girls’ visit. The visa was issued and on September 7, 2013, Zhang Lin’s daughters boarded a flight to San Francisco. They were greeted on arrival by Reggie and her husband Robert. Both Ruli and Anni have been granted political asylum in the US.

A short while later, Reggie, Robert, Ruli, and Anni came to visit me in San Francisco where we enjoyed lunch at a Japanese restaurant near the office. Reggie and Robert provided a safe and caring home for the girls in the ensuing years, all the while continuing to advocate for Zhang Lin in China.

Reggie and I, along with Jing Zhang, President of Women’s Rights in China, continued to work closely together to get the Chinese government to allow Zhang to leave China and to secure a visa for his travel to the US.

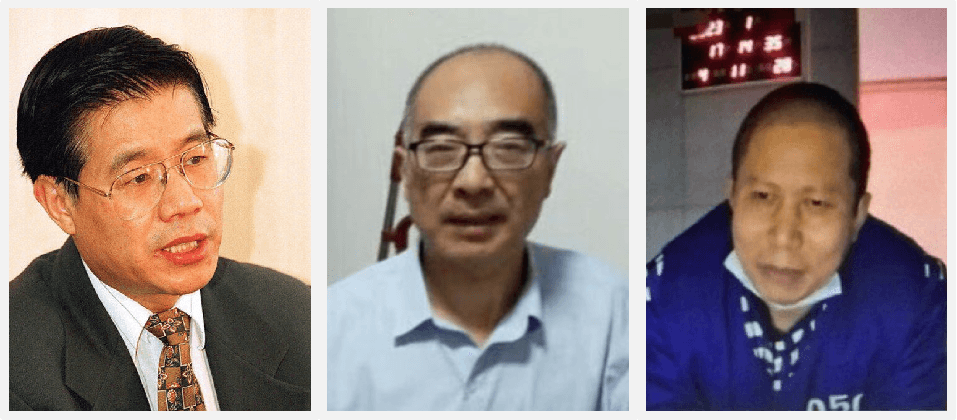

Heart of an Activist

Since his arrival in the US in January 2018, Zhang Lin has been at the forefront of criticizing the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). He has spoken at public events in New York, Washington DC, Seattle and elsewhere. He has organized protests and been a columnist at two newspapers. He established his own YouTube channel, Zhang Lin’s Vision, with more than 100,000 subscribers. It garners about one million views every month.

Zhang Lin is pessimistic about the future of democracy in China. He has no plans to return to the country where he was born and where he toiled for decades, in and out of prison, to realize the dream of democracy and respect for human rights.

The Significance of Zhang Lin’s Case

Of the hundreds of cases I’ve worked on for more than three decades, Zhang Lin’s case stands out:

- He has been under surveillance by agents of the CCP and the government it controls for nearly his entire adult life, from the time he was placed on the list of “targeted people” in 1980 to the present day in the US;

- It marked one of the first instances of my using “open sources” — radio broadcasts and provincial newspapers – to identify political prisoners;

- Zhang witnessed and participated in three of the major pro-democracy movements in China since the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976 – Democracy Wall, the June 4th protests, and the China Democracy Party. Members of the New Citizens Movement joined protests over the refusal of authorities to allow Zhang Lin’s daughter to attend school;

- He was incarcerated in the major carceral facilities used to house political prisoners: police stations where administrative detention is served, detention centers, designated locations for residential surveillance, and prisons;

- He was deprived of his political rights on multiple occasions;

- He was convicted of five offenses used to incarcerate political and religious prisoners: counterrevolution, hooliganism (counterrevolution and hooliganism were removed from the Criminal Law in 1997), illegal border crossing, inciting subversion, and gathering a crowd to disrupt traffic or public order;

- Despite obstacles, Zhang Lin was able to escape China, with the assistance of Reggie Littlejohn, American officials, and me, to reunite with his daughters in the US.

Time Spent in Detention

When I interviewed Zhang Lin for this JKR, we discussed many topics, including his experiences of incarceration. In addition to time spent in police stations, locations used for residential surveillance and prisons, Zhang Lin spent more than five years in 10 different detention centers.

“Cruelest jails in the world”

Based on his experience, Chinese detention centers are the cruelest jails in the world. The Chinese prison authorities studied all four of the detention models – traditional Chinese, Russian, Japanese, and British – and incorporated features of each into China’s current detention model.

“…I was severely mistreated in detention and reform through labor centers. The worst was the Guangzhou labor camp where the guards acted like wild beasts. I was subjected to electric shocks and beaten mercilessly in Chinese detention centers. I was kicked in the back, which contributed to cervical stenosis, a condition that plagues me to the present day. I have to move my neck every 30 minutes, or it will become very stiff. I developed a bad tooth ache in Tongling Prison but was denied medical treatment.”

In detention and reform though labor centers, Zhang Lin encountered at- risk detainees including Christian missionaries, Falun Gong practitioners, and those awaiting execution.

“…I tried to help the missionaries and unorthodox religion practitioners, even challenging a guard to a fight to dissuade him from hurting an elderly Protestant.”

(Members of Zhang Lin’s family were Christian for several generations. He converted to Christianity in 2020, after his arrival in the US.)

Zhang had less opportunity to interact with at-risk prisoners in prisons. Such prisoners would meet occasionally in the prison yard, but they were not grouped together in cell blocks devoted to political prisoners as is the case in some Chinese prisons.

Those awaiting execution

Knowing that China keeps those convicted of death penalty in detention centers while pending appeals or waiting for executions, I asked Zhang if he had seen any of those inmates.

He recalls being part of a group of 20 inmates assigned while at the Bengbu Detention Center to keep watch over those awaiting execution.

“…After an inmate received a death sentence, he was immediately shackled and handcuffed and then transferred to a new cell. The “watch” group was divided into five smaller groups of four inmates who monitored the death row inmates to insure they didn’t assault other inmates or commit suicide or otherwise hurt themselves.”

According to Zhang, a possible reason for the surveillance was to make sure that their organs could be harvested, if necessary, for use in organ transplants.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.