EVENTS

Dui Hua and China’s Supreme People’s Court Hold Webinar on Juvenile Justice Reform

On April 13 in San Francisco, April 14 in Beijing, the Dui Hua Foundation (Dui Hua) co-hosted an expert exchange with the Research Department of China’s Supreme People’s Court (SPC). The exchange, which was held virtually, brought together judges, judicial experts, and youth workers from both countries to discuss “Topics in Juvenile Justice Reform.” A short video of the key points and highlights is now online.

The program, which lasted nearly two hours, was months in the planning and featured two panels – one from the United States and one from China – exchanging presentations on topics relevant to juvenile justice. Simultaneous translation for the event was provided by the SPC. The full program is available on Dui Hua’s dedicated website, GirlsJustice.org, which also hosts videos and materials of past exchanges.

Deputy Director General Jiang Jihai of the SPC Research Department moderated the Chinese presentations while Dui Hua Executive Director John Kamm, assisted by Judge Leonard Edwards, moderated the US presentations.

The panelists addressed multiple topics, ranging from new areas like cyberspace regulations to long-discussed topics like record sealing for juveniles. The US panelists were:

- Judge Leonard Edwards, Judge (Retired) Santa Clara County Superior Court and juvenile justice reform activist, presenting on “Recent Developments in Record Sealing of Juvenile Offenders”

- Judge Mike Nash, Head of the Los Angeles Office of Child Protection and former Presiding Judge of the Los Angeles Juvenile Court, presenting on “Congregate Care in the United States”

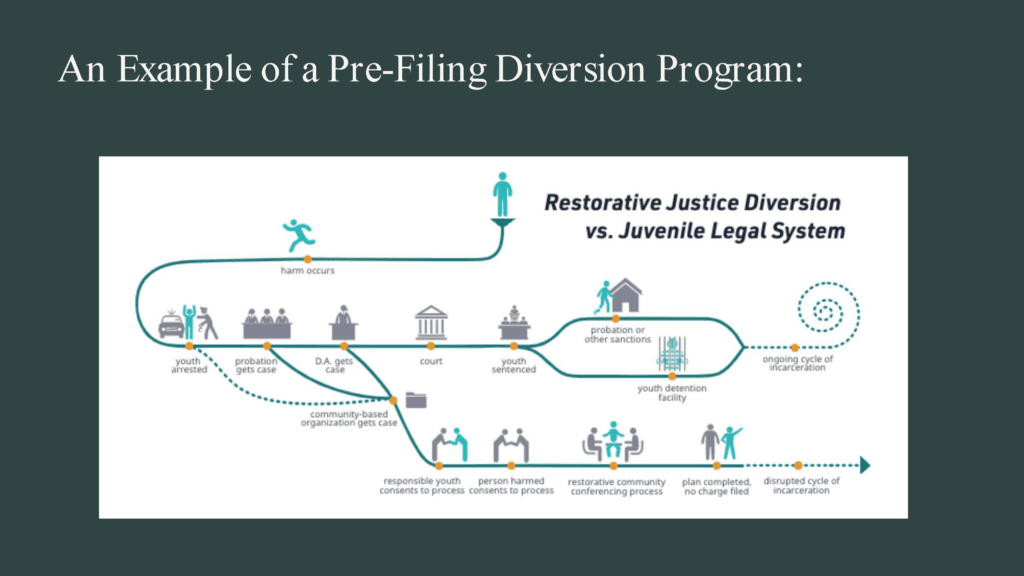

- Jean Roland, Managing Attorney of the Juvenile Division of San Francisco District Attorney’s Office, presenting on “The Role of the Prosecutor in Juvenile Court.”

The Chinese panelists were:

- Chief Judge Sun Mingxi, of the Juvenile Division of Beijing Internet Court, presenting on “Practices of Beijing Internet Court on the Protection of Legitimate Rights and Interests of Juveniles in Cyberspace”

- Deputy Chief Judge Fan Yu, of No.1 Criminal Division of Sichuan High People’s Court, presenting on “Practices of Family Education Guidance System in Sichuan Province”

- Lü Anqi, an official of Juvenile Rights and Interests Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Youth League, presenting on “Actively Promoting the Role of Popular Organizations, Improving the Social Support System for Judicial Protection of Juveniles.”

The American audience consisted of experts from the Child Welfare Council, the Los Angeles office of the Department of Justice, Child Custody Evaluation Services, San Francisco Superior Court, the University of Hawaii, and the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office. Among Chinese audience members, the SPC invited judges and officials of the No. 1 Criminal Division, No.1 Civil Division, Research Department(研究室), Law Reseach Institute(法研所), and the International Cooperation Department of SPC.

The event included a Q&A session, during which US and Chinese panelists answered submitted questions from their counterparts. The Chinese panel asked US presenters about topics including preconditions for unsealing juvenile records, regulations on cybercrimes affecting minors, and trends in juvenile delinquency. The US panel asked their Chinese counterparts about congregate care procedures, treating juvenile offenders as adults, and about the decline in the number of juveniles sentenced by Chinese courts over a ten-year period.

In response to the latter question, Judge Jiang provided valuable information on recent developments in juvenile justice reform in China. The number of juveniles tried by Chinese court fell from 56,000 in 2013, the year the amended Criminal Procedure Law (CPL) with juvenile protections took place, to 28,000 in 2022. Seven percent of those tried were females, and the majority of all juveniles tried were 16 or 17 years old. Trials of juveniles took place without interruption during the Covid pandemic. Judge Jiang attributed the drop in the number of juveniles tried to the implementation of revised laws, notably the CPL and the Juvenile Delinquency Prevention Law.

Starting in 2008, Dui Hua and the SPC have cooperated on nine programs. Seven have been devoted exclusively to juvenile justice while two were international symposia, one on women in prison in 2014 and the other a webinar series on girls in conflict with the law, which ran from October 2020 to April 2021.

PUBLICATIONS ROUND UP

Featured: Human Rights Journal, May 9, 2023: UN Submission Focuses on Persecution of Women in Unorthodox Religions

The number of women incarcerated in Chinese prisons has grown faster than the population of incarcerated men over the past decade, and women are disproportionately represented in criminal cases involving unorthodox religious groups. These are two of the findings highlighted by Dui Hua in its submission to the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)’s review of China.

Human Rights Journal, May 2, 2023: Eleven Years on the Lam: Indictment of a Tibetan “Robber”

Protests swept across the Tibetan plateau ahead of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. More than a decade later, China continues to track down and punish pro-independence protesters who took part in the unrest, some episodes of which turned deadly. An indictment uncovered by Dui Hua reveals how one protester was ultimately found and punished years after their alleged crime.

Human Rights Journal: Child Welfare with Chinese Characteristics, Part I: Rights & Responsibilities of Family & Schools (April 4, 2023) & Part II: An All-of-Society Effort (April 6, 2023)

On June 1, 2021, the second revision of the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of Minors (hereafter Protection of Minors Law) came into effect. The revision introduced 60 new articles into law. During the Joint Program on Child Welfare Laws (JPCW) webinar hosted by Dui Hua in April 2022, panelists from the Supreme People’s Court of China (SPC) spoke in depth about the revisions to the Protection of Minors Law across six key protection areas: family, school, society, internet, government, and the judiciary.

This article explores China’s child welfare legislation by drawing on the relevant legislation, white papers issued by Chinese Communist Party organs, and remarks made during Dui Hua’s 2022 JPCW webinar. Part I focuses on the obligations of the family unit and educational institutions in child welfare. Part II looks at the designated roles of online entities, government bodies, the judiciary, and society at large in ensuring the welfare of the child.

See Also: Prisoner Updates 2023 #4: Author of a well-known blog sentenced for incitement in Shanghai; Clemency granted to “cult” prisoners in Guangdong women’s prison; House church leaders released; Veteran activist Dong Guangping remains missing

JOHN KAMM REMEMBERS

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s human rights advocacy prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999.

Half the Sky

In March 2006, the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) was established, replacing the much-criticized Human Rights Commission. One of the principal tasks of the HRC is to oversee the process known as Universal Periodic Review (UPR). Every four to five years, the human rights records of United Nations member states are examined with respect to their compliance with international human rights norms.

China’s first UPR was held in Geneva in 2009, followed by its second UPR in 2013 and its third UPR in 2018. China’s next UPR will take place in early 2024. The Dui Hua Foundation (Dui Hua), which is in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (ECOSOC), has attended all of China’s UPRs, and has made submissions at each one. It will make a submission to China’s January 2024 UPR in July 2023. It intends on attending China’s fourth UPR.

One of the subjects examined at UPRs is whether the reporting state has issued invitations to special procedures (special rapporteurs and treaty bodies) to the reporting state. There are currently 59 special procedures.

After China’s first UPR, it invited the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Mr. Olivier de Schutter, to visit the country at the end of 2010, no doubt thinking that this would be a relatively benign and risk-free visit. Beijing is very sensitive to any criticism of its human rights record by international bodies, especially the HRC and its special rapporteurs and treaty bodies.

Upon his return to Geneva from his mid-December 2010 visit, Mr. de Schutter made a report. While noting the advances made by China, the report also referenced “specific challenges” that needed to be addressed, including agricultural sustainability and food insecurity in poor and rural areas, food safety, and land degradation and pollution. An entire section was devoted to criticizing China’s policies targeting nomadic herders in Tibet and other minority areas. Beijing was not happy, and no more invitations to special procedures were issued in 2011 and 2012.

As China approached its third UPR to take place in October 2013, its Ministry of Foreign Affairs considered whether or not to invite a special procedure to visit the country. I was asked for my advice. I was inclined to recommend the Working Group on the Issue of Discrimination Against Women in Law and Practice (WGIDAWLP) but first I needed to ascertain whether the working group was interested in making a formal visit.

I asked friends in Geneva and was told that the group had only been established in 2010 and as such it was the “new kid on the block.” Many other special procedures were waiting for invitations. I decided to ask the working group anyway and was pleasantly surprised to learn that it was interested to visit China. I made a suggestion to the MFA that the group be invited.

I arrived in Geneva from Oslo on Sunday October 20, 2013, and checked into my usual haunt, the Hotel Ambassador. I had dinner at a nearby Chinese restaurant and settled in for the night. In addition to attending China’s UPR, where I was informed that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had accepted my suggestion to invite the working group, I met with American and Chinese diplomats, UN officials, the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Assembly, and the president of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Peter Maurer.

At my meeting with the WGIDAWLP on October 24, I was thanked for my work lobbying the Chinese government to issue the invitation – the visit took place two months later in December 2013 – and discussed their and UNOHCHR’s possible attendance at Dui Hua’s international symposium on Women in Prison (the Bangkok Rules), set to take place in Hong Kong in February 2014.

Women in Prison

The symposium took place as planned. Dui Hua partnered with the University of Hong Kong and China’s Renmin University. A member of the WGIDAWLP, Elenora Zielinska, attended and presented a paper on the group’s 2010 visit to China. The OHCHR sent a representative, Adwoa Kufuor, to make a presentation on the treatment of women prisoners under international human rights law.

China sent the largest delegation to the symposium; it included scholars from the Supreme People’s Court and several research institutes and law schools who presented papers on domestic violence, women law enforcement officers, and treatment of female juvenile offenders in Beijing, and, separately, treatment of female prisoners in Hong Kong. (Hong Kong has one of the highest percentages of women prisoners of any country or territory in the world). Findings of a survey of five places of detention for women in China, commissioned by Dui Hua and conducted by scholars at Renmin University led by Professor Cheng Lei, were presented.

The symposium’s delegates visited Hong Kong’s largest women’s prison and held discussions with the territory’s authorities in charge of women prisoners. Most important, the symposium, attended by one of the judges tasked with reviewing death penalty decisions, contributed to the overturning of a death sentence for a victim of domestic abuse who murdered her husband.

On a follow-up visit to Beijing, I was advised by a senior official of China’s National People’s Congress that the legislative body would consider where the Bangkok Rules could be incorporated into Chinese legislation.

Girls in Conflict with the Law

The International Symposium on Women in Prison set the table for the International Symposium on Girls in Conflict with the Law. Unlike the women in prison symposium, which was held in person, the girls in conflict with the law (GCIL) symposium was held virtually due to the Covid-19 pandemic. From October 2020 to March 2021, 12 webinars featured experts from 18 countries discussing topics related to the treatment of girls in the justice systems of countries on five continents.

The final topic was a presentation by China’s Supreme People’s Court – “Special and Priority Protection of the Legitimate Rights and Interests of Underage Girls in Accordance with the Law,” featuring Dui Hua’s long-time partner Judge Jiang Jihai and his colleagues.

There is no contradiction between Dui Hua’s work on women prisoners and girls in conflict with the law, on the one hand, and our work on political and religious prisoners on the other. From the earliest days of my advocacy to the present, I have worked on numerous cases of women and girls who have been detained and imprisoned, including Ngawang Sangdrol and the Drapchi nuns, Liang Shaolin and dozens of other women subjected to coercive measures for practicing unorthodox religions, American citizen Sandy Phan-Gillis, and Rebiya Kadeer and other Uyghur women. To Dui Hua, Mao Zedong’s claim that “Women hold up half the sky” is more than a slogan. It is a core belief at the center of our work.

Visit the “John Kamm Remembers” page to read more stories like this, view photos from this period in history, watch videos about the origins of modern US-China engagement and learn how the decisions of the past are shaping our future.

Subscribe here to receive Dui Hua publications by email.