|

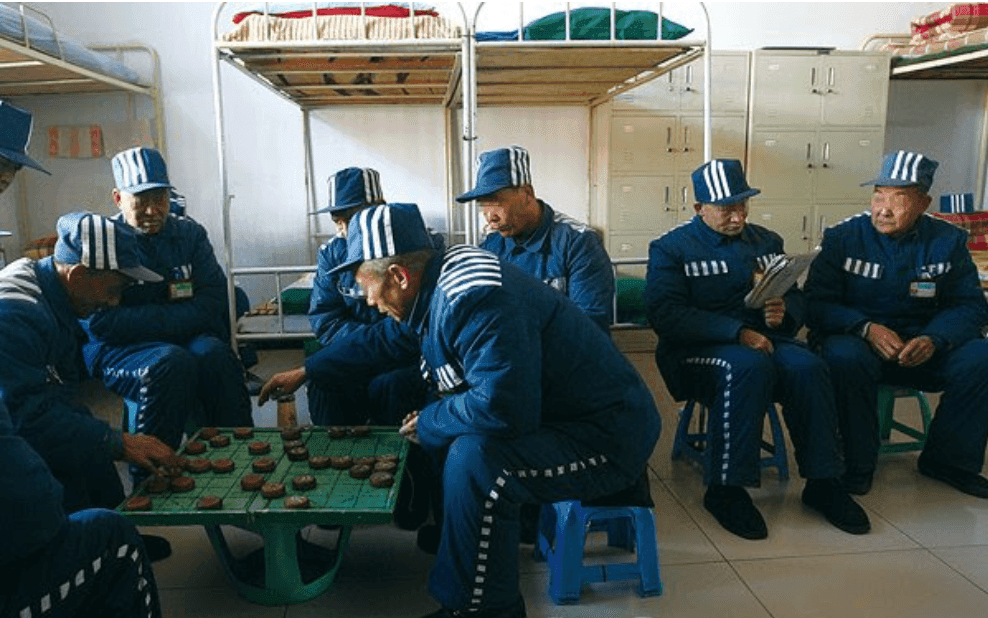

Men play chess inside the “elderly” prisoner cell block of Henan No. 3 Prison. Photo Credit: Pan Xiaoling, Southern Weekly |

It’s an old problem and a new one. The United States and China are facing demographic challenges from aging populations, and the trend is particularly acute in prisons. In the US, longer sentences and mandatory minimums have contributed to a historically unprecedented level of incarceration, resulting in prisons that are both growing and growing grey. According to a Human Rights Watch report, the number of people age 65 or older in US state and federal prisons grew 63 percent between 2007 and 2010, compared with growth of less than one percent in the overall prison population. This statistic underscores why the plight of older prisoners is now often called a crisis.

While definitions vary, the proportion of “elderly” prisoners in both the US and China may be around 3–4 percent of national prison populations. In China, prisons generally classify people age 60 or over as “elderly”—some sources say the age is 55 for women—but prison statistics are not often in the public domain. Using available data, Chinese academics have speculated that elderly people account for less than 3 percent of Chinese prisoners and, at 3 percent, that would be about 50,000 people. In the US, the minimum age of an “older” prisoner varies by state from 50 to 70. Using the Chinese benchmark for comparison, there were 59,700 people 60 or over in state and federal prisons in 2010, accounting for 3.9 percent of the US prison population, according to data from the US Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS).

Dui Hua previously highlighted the indignity and monumental costs of requiring people to confront aging and illness behind bars—BJS data indicate that more than 8,000 people age 55 or over died of illness in US state prisons between 2001 and 2007. Building on these humanitarian and fiscal arguments, this article looks at recidivism rates as support for making elderly prisoners prime candidates for more tempered and alternative sentencing, as is already the case in China.

Age and Recidivism

“Of all the causes which influence the development of the propensity to crime, or which diminish that propensity, age is unquestionably the most energetic,” wrote Belgian sociologist Adolphe Quetelet in his 1842 classic, A Treatise on Man and the Development of his Faculties. Quetelet, arguably the world’s first crime statistician, based his work on French crime data from 1826 to 1829. Recent research continues to support his theory that the incidence of crime peaks in adolescence or early adulthood and then declines.

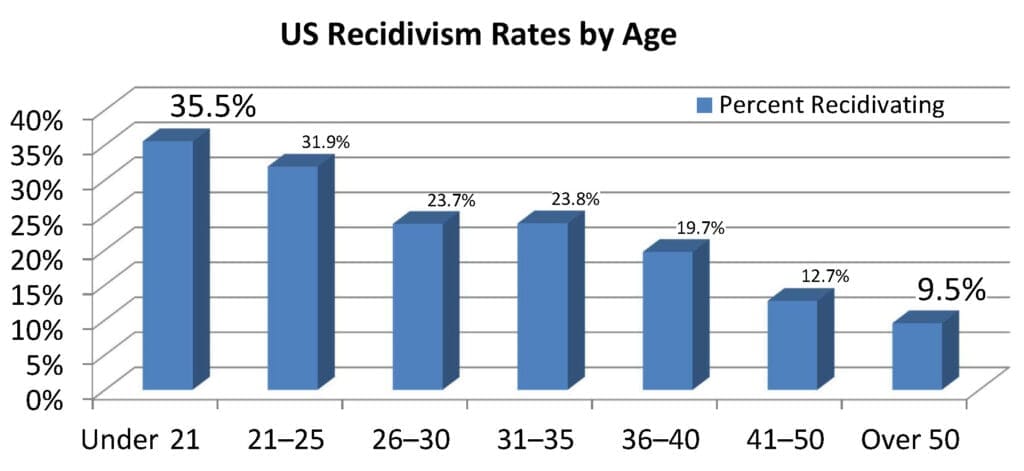

A comprehensive analysis of people in the US federal prison system found that recidivism declined consistently with age. This 2004 study, which was produced by the U.S. Sentencing Commission, reported that people over age 50 had a recidivism rate of 9.5 percent, compared with 35.5 percent for people under 21 (see graph). According to a 1998 study from the Coalition for Sentencing Reform, only 3.5 percent of people 55 or older were re-incarcerated within a year of release, compared with 45 percent of those ages 18 to 29.

|

Recidivism refers to re-arrest or re-conviction within a 24-month period. Data: U.S. Sentencing Commission |

Discussing the reason for the link between age and law-breaking, some experts point to biological and hormonal changes. Others highlight the influence of stable social relationships, particularly marriage, and physical degeneration. Whatever the explanation, any criminal justice system that takes public safety into account cannot deny that older people generally pose less of a danger to society—in terms of recidivism and persistence of crime—than younger people.

A Mature Approach to Criminal Justice

In February 2010, China’s Supreme People’s Court released an opinion on the implementation of the national policy of combining leniency and severity (宽严相济). The opinion calls for the use of discretion in granting elderly people lenient punishment (Para. 21) and lists them as eligible for leniency in sentence reduction and parole (Para. 34). One of the stated purposes of the policy is to prevent and reduce crime.

|

In Anhui, 151 people age 60 or over received sentence reductions and parole in January 2011. Photo credit: Legal Daily |

Additionally, several courts have cited generally lower rates of recidivism and lower public safety risk as reasons to treat older people differently. Although some US jurisdictions offer compassionate release programs for terminally ill prisoners, federal and state parole policies do not typically consider age, and the move to determinate, or non-discretionary, sentencing has precluded such discretion.

Last year, China included provisions for the elderly in amendments to the Criminal Law. Unlike prison guidelines that use age 60, however, the law uses age 75 to delineate elderly prisoners. Some critics have argued that this age is too high to have any real impact and is out of step with Chinese criminal justice regulations that choose age 70. That said, as a move towards more humanitarian treatment, the amended law makes elderly people eligible to receive suspended sentences (Art. 72) and receive leniency and reduced sentences (Art. 17).

Defendants in this age group are also exempt from capital punishment, except “in cases where death is caused by especially cruel methods.” As an indication of how little impact this will have, the number of Chinese capital cases involving people over 70 is fewer than 10 cases per year, compared to the estimated 4,000 people executed in China in 2011. By contrast, the percentage of people over 60 on US death row quadrupled between 1999 and 2009 to more than 8 percent (of 3,173 people). While the US takes more time than China to carry out executions, the number of elderly people executed in the US has risen in recent years. Between the reinstatement of capital punishment in 1976 and 2002, only one prisoner over age 65 was executed. Since then, at least three have been put to death.

Life Without Possibility

Another contentious and divergent area relevant to aging prisoners is life without the possibility of parole. The US is a global outlier in its extensive use of the sanction and its application of the sentence for nonviolent crimes. As of 2008, more than 41,000 people in US prisons were serving sentences of life without the possibility of parole, according to data compiled by The Sentencing Project. In China, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain, the sentence, which has the potential to increase the elderly prisoner population and virtually guarantees death behind bars, does not exist.

People, young and old, should be held accountable for their actions, and criminal sanctions are an important way to do this. At the same time, courts should have ways of recognizing the low risk that aging prisoners pose to free citizens and the dignity of dying outside prison. China’s criminal laws are moving towards such discretion, while sentencing guidelines and mandatory minimums are holding US judges back. A more balanced US policy towards elderly prisoners would universalize the possibility of parole and recognize that while justice requires blindness, it also requires vision. ■

China’s Oldest ESS Prisoner?

Chen Zhaolu (陈兆祿) was born on December 9, 1917, in Guangzhou. He became a Hong Kong resident in 1968 when he started working for Xinhua News Agency—then China’s de facto consulate in Hong Kong—and retired in 1985 at age 67. Chen remained in Hong Kong with his immediate family, including two sons and three daughters, but traveled regularly between Hong Kong and Guangzhou.

Eighteen years after retirement, on November 25, 2003, Chen was detained in Guangzhou on suspicion of “endangering state security” (ESS). That year, a number of former Hong Kong Xinhua employees were arrested on charges of espionage, an ESS crime, but it is not known whether Chen’s detention was part of a broader investigation.

On January 19, 2004, the Guangzhou Intermediate People’s Court sentenced Chen to 13 years’ imprisonment. At age 86, he was incarcerated in the elderly prisoner cell block of Guangzhou Prison, Guangdong’s “model prison.” Chen was given a nine-month sentence reduction in 2006 and a 16-month sentence reduction in 2008. He was granted medical parole for a period of three years on September 2, 2009, and is reported to be in the care of his family.

Medical parole, as with parole granted for good behavior, is a sentence served outside prison. Dui Hua believes that Chen Zhaolu, age 94, is the oldest prisoner serving a sentence for endangering state security in China. Given his advanced age and subsequent special needs, prison authorities, an informed source said, are unlikely to re-incarcerate Chen when his medical parole expires on September 1, 2012. According the source, Chen’s remaining sentence is likely to be commuted.