When US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited China in February, US-China relations were shaky, and the human rights dialogue to be assumed by the new Obama presidency was fraught with questions. In the prior month, the Bush administration had failed in its attempt to conduct a final dialogue session with China, Beijing had redacted President Obama’s inauguration speech, and Secretary of the Treasury-designate Timothy Geithner had called China a currency manipulator at his confirmation hearing. In addition, the incoming administration had its hands full on the home front with a financial crisis and two costly wars. It was the kind of period—tense, overwhelming, and uncertain—when brief remarks can speak volumes.

And so it was that, en route to China, on the final leg of her trip through Asia, Clinton made impromptu comments to reporters traveling with her. Regarding China’s human rights record, she stated, “We know what they are going to say because I’ve had those kinds of conversations for more than a decade with Chinese leaders.” She went on, “We have to continue to press them. But our pressing on those issues can’t interfere with the global economic crisis, the global climate change crisis, and the security crisis.”

Her words caught fire in the press and were widely interpreted to mean that US China policy would be far more conciliatory on human rights than Obama had suggested during his campaign, when, for instance, he called on President Bush to boycott the opening ceremonies of the 2008 Summer Olympics over Beijing’s policies in Tibet. After Clinton’s comments were reported, critics suggested that Obama’s team was going to take the familiar tack of recent administrations: talk tough on human rights but, above all else, maintain the “strategic partnership” with China.

Remarks and Realities

The simple fact is that US human rights policy toward China does not hinge on the thoughts or desires of the executive branch, let alone any one person—even someone as powerful as the secretary of state. There are structures in place to deliberate over policy and to instill checks and balances for decision-making, as well as human rights reports to be filed with Congress. A week after Clinton’s visit to Beijing, the State Department released its annual country report on China’s human rights and concluded that human rights in the country had worsened in 2008. In March, her department once again listed China in its International Religious Freedom report as a “country of particular concern” over alleged violations of religious freedoms.

In a year of major anniversaries, including the Tibetan uprising in 1959, Tibet remains a major flashpoint for human rights attention. Clinton brought up the Tibet issue, though only briefly, during her visit to Beijing. The US Congress and EU Parliament later passed resolutions calling for improved human rights policies in Tibet, with both moves strongly condemned by China. South Africa’s denial of a visa to the Dalai Lama to attend a peace conference—an apparent gesture of solidarity with Beijing—was met with widespread anger and dismay.

The US executive branch also must consider the rulings of the courts, whose decisions can heavily influence the direction of policy and, in some cases, the image of the United States. Since revelations of mistreatment of prisoners in Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo Bay surfaced, it has become more difficult for the United States to criticize China’s treatment of prisoners in Tibet and elsewhere. Obama wants to close Guantánamo and toughen US policy on torture, but one of the thorniest issues facing the administration is what to do with the Uyghurs detained there. Just when it appeared the last hurdle had been cleared to settle the group in the United States, a federal court overturned the verdict of a lower court that would have enabled the move to take place, leaving the new administration in a difficult fix.

In the area of workers’ rights, the Obama team is on target to be more proactive than the previous US leadership. The AFL-CIO, encouraged by the president’s interest in protecting labor, is expected to resubmit a petition—twice rejected by the Bush administration—that claims China’s lack of workers’ rights gives the country an unfair trade advantage. Like labor policy, concerns over the environment also speak to key constituencies of the Democratic Party. Energy Secretary Steven Chu has advocated tariffs on carbon-intensive imports to protect US manufacturing, this coming one day after a top China climate envoy warned that such tariffs would set off a trade war since industrializing countries would have to bear huge emission costs.

Human Rights As Usual For China?

Events that took place around Clinton’s visit to China, both at the United Nations in Geneva and in Beijing, should spur US policymakers and diplomats to be focused on engaging the Chinese government on human rights. In early February, China scored a public relations coup with its deft handling of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of its human rights record before the UN Human Rights Council. Some UN member states, mostly close Chinese allies criticized for their own alleged rights abuses, praised long-standing Chinese practices that have been broached in dialogues. Egypt supported China’s use of the death penalty, Sudan endorsed “reeducation-through-labor,” and Cuba backed China’s strict punishment of human rights defenders whose activities, said Cuba, threaten the interests of China and the Chinese people.

In response to recommendations on how to improve its human rights record, China rejected virtually every one that spoke to increasing civil and political liberties (but said it would “consider” reducing the number of crimes that carry the death penalty). Chinese representatives defended the country at every turn, making the now-familiar argument that economic and social rights were more “fundamental” than civil and political rights. They gave no indication of when the country plans to ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Many in the human rights community had hoped that the UPR would be a new platform for frank and accountable human rights dialogue. Even in mid-January, State Department professionals had expected the United States to play an active role at China’s UPR and dispatch a team from Washington that would pose questions and make recommendations. In the end, however, no US delegation was sent, and no comments or recommendations were raised—yet another indication of the indecision within the new Obama administration over how to deal with China on human rights. To make matters worse, the summary report by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights was criticized for omitting tough recommendations for China, especially those about religious and minority groups and human rights lawyers and defenders. The outcome seemed to further bolster China’s stature in the Human Rights Council, a body the United States will seek to join in part to wield more influence on issues of universal rights.

Despite China’s glowing performance at the UPR, the international community is by no means won over by the general state of affairs in China. According to recent poll numbers, China’s popularity has sunk over the past year, especially among democratic countries, even as China garnered the world’s compassion after the Sichuan earthquake and respect for hosting a spectacular Summer Olympics. As the United States has discovered and China may yet, a country whose human rights record is found wanting can suffer a sharp drop in credibility overseas.

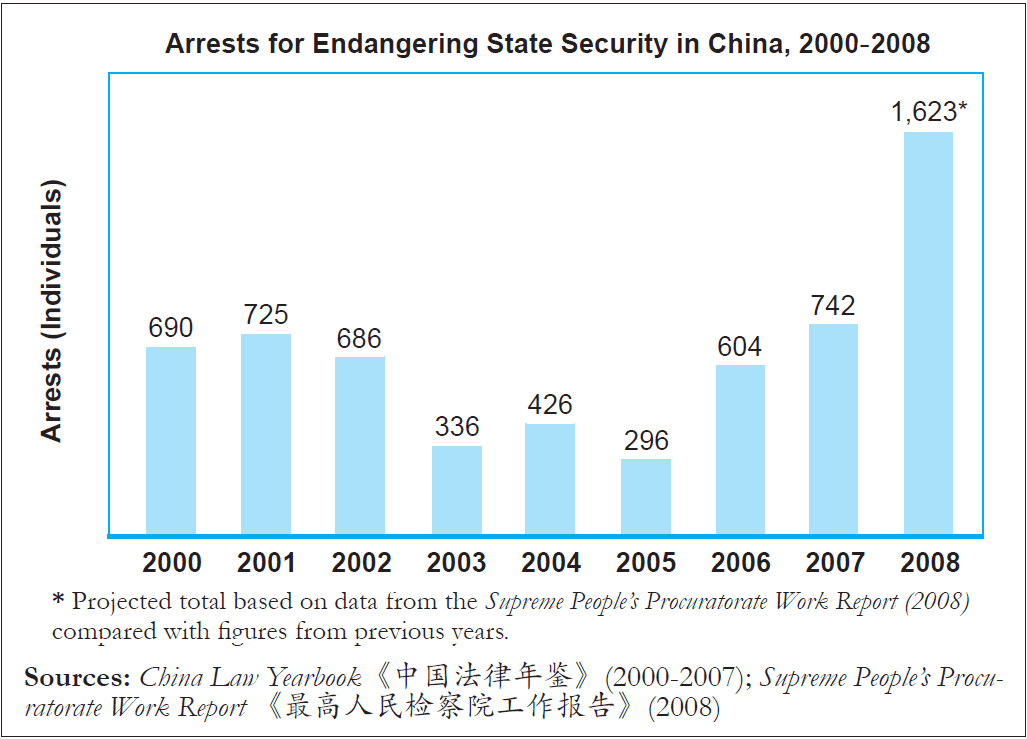

Official rhetoric at the annual session of the National People’s Congress (NPC) in March may give further impetus for the United States to work conscientiously on issues of China’s human rights. Wu Bangguo, chairman of the NPC’s Standing Committee, drew out an explanation about how democratic pillars such as a multi-party political system and independent judiciary were incompatible with Chinese conditions. He underscored that China requires Communist Party leadership and would otherwise be “torn by strife.” This line of thinking follows a tumultuous year in China that saw an estimated 100,000 mass incidents, widespread unrest in Xinjiang and the Tibetan plateau, a doubling in the number of arrests for “endangering state security” crimes (see graph), and a demand by intellectuals and dissidents in “Charter 08” for China to adopt multi-party governance. It is almost certain China will experience greater social unrest in the near future due to the decimation of its export manufacturing sector, among and other problems with human rights ramifications.

When, How Will Dialogue Resume?

At a meeting between Chinese President Hu Jintao and President Obama in London on April 1, it was decided that the next session of the official human rights dialogue would take place “as soon as possible.” It was also announced that the countries are establishing an annual Strategic and Economic Dialogue (SAED) to combine and upgrade the twice-yearly Strategic Economic Dialogue and US-China Senior Dialogue that were features of the Bush administration. Since human rights will be discussed at the new SAED, it is possible that the human rights dialogue itself will take place around the same time. However, President Obama and Secretary Clinton are many weeks, if not months, away from having assistant secretaries of state for East Asia and human rights. Until the team is in place, holding a human rights dialogue with China is not possible.

At the UPR, China asserted that it holds more than 20 human rights exchanges with foreign countries. But neither Chinese nor foreign participants in these dialogues are satisfied with the process or the results. The EU-China dialogue has yet to recover from the shock of China’s execution of Wo Weihan, father of two EU citizens, on the last day of the November session. Several Western dialogue partners have complained that, since July, virtually no new information has been provided by the Chinese side on cases of concern. These same partners have noted that China has become increasingly adept at raising human rights issues in the country with whom they are holding dialogues, such as state control of religion in Norway, police brutality in the UK, and the treatment of a Chinese journalist working for the German state broadcaster Deutsche Welle.

Viewed broadly, the dialogues have become dialogues of the deaf in which each side simply lays out a defense of its own record while attacking the rights record of the other side. In this sense, Secretary Clinton was correct when she said that, on issues of human rights, each side has their own positions, well known to all. The challenge is to move beyond the present stalemate so that the human rights dialogues are equal part cooperation on such issues as juvenile justice and also respectful disagreement on issues like freedom of expression and association.