The year 2009 has been one of important anniversaries in China, some condemned on human rights grounds, like the suppression of the pro-democracy protests in Beijing and other cities in 1989 and the crackdown on the Tibetan uprising fifty years ago. On October 1, Beijing celebrated the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic with displays of military might and fireworks, but not with a special pardon of long-serving prisoners as many inside and outside China had hoped for.

This year will also be remembered as one of growing US-China ties more in tune with another anniversary: the normalization of US-China diplomatic relations in 1979. At the first round of the Strategic and Economic Dialogue in July, the countries agreed to cooperate on energy and climate change policies and expand military and cultural exchanges. In November, President Obama’s first visit to Beijing since his election is set to push initiatives to spur global economic recovery, fight terrorism, and respond to pandemic diseases. Another session of the human rights dialogue is expected to occur by year’s end or in early 2010.

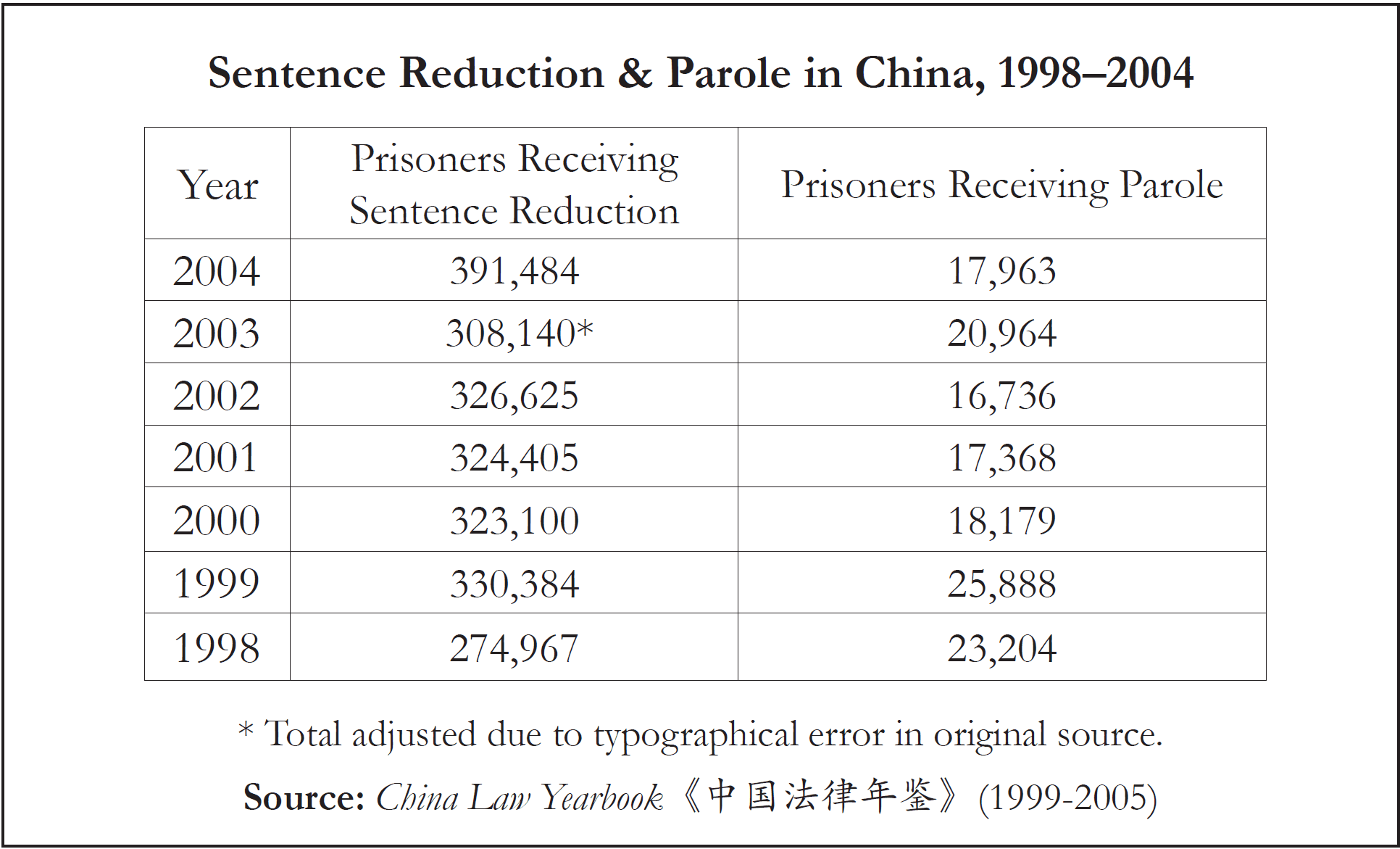

The agreement to reconvene the US-China Legal Experts Dialogue, announced in September during the visit to Washington by Wu Bangguo, chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC), is one more chance for the two countries to sit down and talk. Between 2003 and the last round in July 2005, there have been three sessions of the dialogue between the Office of Legal Affairs of the US State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor and senior Chinese judges of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC), each focusing on sentence reduction and parole in the two countries.

Speaking of Sentence Reduction & Parole

The previous sessions of the legal exchange dialogues were inspired by Dui Hua’s 2003 inquiry to the SPC about whether sentence reduction and parole for “counterrevolutionary” prisoners in China were still being “strictly handled” even after removal of the crime of counterrevolution from the Criminal Law in 1997. These sessions concluded with the SPC clarifying that all prisoners, including those serving sentences for counterrevolution, enjoyed equal access to sentence reduction and parole. The SPC explained the term “strictly handled” means that all sentence reduction and parole decisions are made strictly in accordance with the law. According to the SPC, no discrimination exists, and if prisoners serving sentences for “endangering state security” (ESS) benefit from sentence reduction and parole at lower rates than other prisoners, it is probably because fewer are willing to confess their crimes. (Dui Hua’s research indicates that political prisoners benefit from clemency at far lower rates than other prisoners.) When asked to issue a written clarification to subordinate courts, the SPC demurred, telling State Department officials that it would convey the clarification through other means.

Dui Hua recently obtained detailed notices on sentence reduction and parole issued by higher people’s courts in Shanghai, Shandong, and Guangdong. The Shanghai and Shandong notices were both issued before the conclusion of the initial legal experts dialogue. The Shandong notice (issued in May 2005) prohibits parole for prisoners serving sentences for endangering state security, mandates that ESS prisoners wait a full year longer than other prisoners before receiving an initial sentence reduction, and that reductions for ESS prisoners must be 12 months shorter than those for other prisoners. The Guangdong notice, issued two months after the last session of the dialogue, provides for more lenient treatment of ESS prisoners than the Shanghai and Shandong notices. In Guangdong, ESS prisoners who display outstanding behavior can be paroled. (In fact, the Hong Kong journalist Ching Cheong was paroled in February 2008.) Still, compared to other prisoners, they have to wait six months longer for their sentence reductions, and their reductions are shorter (six months and not 12 months).

Although strictures are looser in some provinces than in others, political prisoners are still discriminated against in China’s sentence reduction and parole system. The next legal experts dialogue should use this information as a point of reference and again press for clarification on sentence reduction and parole provisions for Chinese serving sentences for political crimes. (See following table on sentence reductions and parole in China.)

The Worst, Best of Times for Dialogue

Like the related human rights dialogue, the next legal experts dialogue will convene during trying times for rule of law in China. In many respects, rights defense work is becoming more dangerous, and free expression and the right to a free trial face serious obstacles. In February, Gao Zhisheng, one of China’s most renowned rights lawyers, was “disappeared.” The Open Constitution Initiative, which promoted Chinese legal reform, was declared illegal this summer, its website shut down, and its head, Xu Zhiyong, arrested on tax evasion charges. Scores of rights lawyers have had their licenses revoked. In broader terms, the number of arrests for political crimes is expected to increase again this year, in part due to the riots in Urumqi in July. Public security forces are vigorously policing the Internet and have detained, arrested, or convicted many citizens for online posts and other electronic communications.

On matters of law, the US and Chinese sides clearly have many points of contention, but historically, Chinese officials have been receptive to inputs from US counterparts in legal exchanges, including those coordinated by NGOs, universities, bar associations, and business councils. After frequent programs on labor law and worker rights, for example, China promulgated the Labor Contract Law and a revised Labor Dispute Mediation and Arbitration Law in 2008. Judging the practical effects of these laws is difficult, but their passage indicates that some Chinese lawmakers are trying to remedy urgent problems. Labor rights are under constant stress in China, and with worker protests on the rise, labor grievances are as likely to play out in China’s streets as in the courts.

A crucial prerequisite for legal discussions is more transparency in the criminal justice system, particularly regarding case adjudication. To this end, the renewed legal dialogue can encourage Chinese counterparts to increase access to verdicts and trials. Some Chinese provinces have started to publish verdicts online, but most courts do not make their rulings public. And while most trials are supposed to be open to the public, including foreign observers, attending trials remains difficult if not impossible, especially in sensitive cases or those involving “state secrets.” Pre-trial procedures in both countries, like the constitutionally-protected right of a defendant to meet with counsel, collection of evidence, and the process for calling witnesses, are all issues worthy of frank and open discussion.

Other Areas Open for Talks

As with labor law, the least mature of China’s legal mechanisms may yield the most space for the United States to work with Chinese partners. China’s fledgling juvenile justice system is one on which dialogue is increasingly robust. The rise in juvenile crime in China and the absence of a national system for trying juvenile cases have inspired China to go abroad and learn from Western models. One of the most successful legal exchanges in recent years was the delegation hosted by Dui Hua from China’s SPC to study the US juvenile justice system (see Dialogue Issue 33). A report on the program was prepared for Premier Wen Jiabao and circulated in Chinese legal circles. Following this positive experience, the SPC has invited Dui Hua to organize a return delegation of American experts to study China’s juvenile justice system in 2010.

Chinese officials are often willing to discuss issues of law and criminal justice undergoing reform, particularly where international observers have recognized progress even when pointing out shortcomings. One such area is the use of capital punishment. Dui Hua estimates about 5,000 Chinese prisoners will be executed this year—still exceeding all other countries combined, but far fewer than earlier this decade. A major factor was restoration of the SPC’s authority of final review over death sentences in 2007, among the most important recent developments in Chinese law.

Very gradually, the cloak of secrecy surrounding capital punishment in China is lifting—both voluntarily and despite China’s resistance—and the legal dialogue can encourage Chinese officials to be even more transparent. Chinese media have increased coverage of the promotion of lethal injection as a replacement for execution by gunshot, and an official media report in August revealed that more than a third of China’s population lives in areas that use lethal injection. Open discussion of this shift (insofar as it provides factual information on capital punishment) is cause for restrained optimism. Furthermore, the Ministry of Health has revealed that prisoners make up 65 percent of donors for the approximately 10,000 organ transplants carried out annually in China, effectively the government’s first admission that thousands of people are executed every year.

But the 2008 case of businessman and scientist Wo Weihan, executed after a closed trial based on secret evidence, revealed that the capital punishment process is still rife with problems—and showed how much needs to be discussed from a basic legal standpoint. In this case, China confronted its first concerted international campaign by foreign governments and NGOs to halt an execution. Worldwide appeals may have triggered internal debate in Beijing over whether to carry out the execution, which took place at least 10 days after the SPC sent down its review decision, and also applied enough pressure for the SPC to issue an interpretation clarifying the procedure for stopping an execution.

Mood & Measure of Dialogue

If the human rights dialogue can serve as a model, revival of the legal experts dialogue does not spell an easy victory for legal reform in China. As the country’s lawmakers debate changes to the Criminal Procedure Law and Criminal Law, it is important to recall that international legal exchanges with China have not always been warmly received. In the past, the Party Central Committee has warned Chinese judges, lawyers, and officials that foreign bodies might use exchanges to infiltrate domestic debates on constitutional reform and has directed Chinese organizations to be cautious and seek to preserve the “stability” of China’s constitution.

As with other talks, the fruits of the US-China Legal Experts Dialogue will be measured in incremental steps and over many years. Perhaps its real value lies in the opportunities it creates for forthright exchange, whether on the treatment of political prisoners, the application of the death penalty, or other issues. Any talks that enable the United States and China to discuss sensitive matters that bear so heavily on rule of law and human rights are worth pursuing, and with gusto.