The In early April, an appeal for the medical parole of Hu Jia, sentenced to 3-1/2 years in prison in 2008 for “inciting subversion,” was rejected. It was the second refusal in less than a year to release Hu due to his deteriorating health, with his family submitting both requests. Hu suffers from cirrhosis, an incurable progressive liver disease, and his condition has worsened in prison. The appeal was made during a spell of bad health and after a growth appeared on Hu’s liver. After medical tests, officials responded by stating Hu’s cirrhosis didn’t meet the conditions for medical parole, and he was returned to Beijing Municipal Prison to continue serving his sentence.

This scenario invites study of how sentences can be reduced and prisoners released in China, and particularly how medical parole functions. China operates an elaborate system whereby a prisoner can receive sentence reductions and complete a sentence early. Prisoners earn points (or demerits) based on daily behavioral assessments. With a certain number of points, a prisoner can apply for a sentence reduction. The review process then requires a court—usually but not always the one that passed the original sentence—to agree to the reduction. After several reductions, courts can commute the remainder of a sentence and order a prisoner released.

Parole may be given to a Chinese prisoner who exhibits exceptional behavior (“good behavior” parole) or performs meritorious service, like stopping a prison riot or creating a useful invention. A court must agree to the parole and the parolee must consent to conditions, such as regular reporting to the public security bureau. Official statistics and reports suggest about 25 to 30 percent of Chinese prisoners receive a reduction each year, but the number of parolees is lower, about 3 to 5 percent. Dui Hua has found that discrimination is codified in provincial regulations against prisoners convicted of “endangering state security” and “cult” crimes; parole is almost never granted to such detainees, and the percentage of them receiving sentence reductions is far lower than for “ordinary” prisoners.

Medical Parole in China: Laws & Practice

China’s medical parole system operates apart from the sentence reduction and parole systems. Medical parole is not as common as sentence reduction with commutation but is used about as often as regular parole. According to the “Measures for Carrying Out Medical Parole for Prisoners” issued by the Ministry of Justice in 1990, “a prisoner who has contracted a serious, chronic illness that has not been successfully treated after a long period of time. . . and who has served at least one-third of a fixed-term sentence, is eligible for medical parole.” A prisoner given a life sentence is eligible for medical parole after seven years. A warden can, in consultation with a provincial-level prison, order the release of a prisoner on medical parole for an initial period of six months. Unlike regular parole, Chinese courts do not intervene in matters of medical parole, and parolees are not required to report to the police. Probably the easiest route for a prisoner to gain early release, medical parole can be granted if a serious medical condition arises during confinement, and at any time for severe illnesses.

Like other forms of clemency, medical parole is commonly granted in times of national celebration. For instance, 44 prisoners in Henan Province were granted medical parole around National Day in 2009, when the prison bureau reduced the sentences of 2,485 prisoners to mark the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China (1,166 prisoners in the province were released by means of commutation and five were granted parole). Large-scale paroles of “elderly, infirm, or disabled” detainees, presumably many released for poor health, also take place around important dates.

As in many other countries, Chinese authorities try to avoid having a prisoner die in detention, so terminally ill patients are occasionally released to die at home. Such was the case with Shao Liangchen, a labor leader during the spring 1989 protests. Shao developed leukemia in prison and was released on medical parole in 2004, dying over a year later. But medical parole has also been handled with less care and compassion: Chen Xiaoming, a housing rights activist, died from a hemorrhage in 2007 just hours after receiving medical parole. Though he suffered from liver cancer, Shanghai authorities had rejected many applications by Chen’s family to parole him for treatment before finally approving his release.

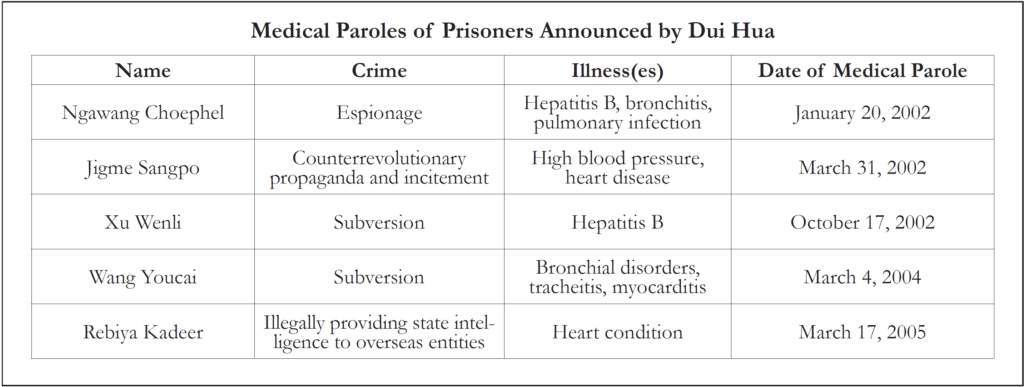

China has granted medical parole to serve politically expedient goals, effectively forcing many Chinese prisoners into exile so they would be less of a nuisance to Chinese leaders. From the early 1990s to early 2005, when China’s campaign against color revolutions began, Beijing secured favor with foreign governments by using medical parole to release high-profile political dissidents whose cases were of great concern abroad, especially in the United States. Medical parolees sent to the United States include, among others, Wei Jingsheng, Wang Dan, Jigme Sangpo, Xu Wenli, and Rebiya Kadeer (see table below for medical paroles announced by Dui Hua). These individuals left China on the grounds that they needed to receive medical treatment—though several were not especially ill—and also with an understanding that they will be re-incarcerated if they return to China.

Since Rebiya Kadeer’s release on medical parole in March 2005, however, no high-profile political prisoners have been given medical parole and sent to the West. Beijing, which now routinely rejects criticism of its human rights record, prefers keeping political prisoners locked up as it tightens social and political controls. And if medical parole is granted to such detainees, it is highly unlikely that they would be allowed to leave China for medical treatment.

Examining Current Cases

Many severely ill political prisoners are caught up in China’s hardened stance. Lobsang Tenzin, imprisoned for 22 years and due to be released in 2013, has diabetes and has suffered from gallstones. Wang Bingzhang is afflicted with multiple illnesses and had a mild stroke in prison. Wang, sentenced to life imprisonment, has served the minimum seven years needed to be eligible for medical parole under Chinese law. The case of Jiang Cunde demonstrates medical parole can be revoked and is conditional on behavior. Sentenced to life in prison in 1987, Jiang was released on medical parole in 1993 after he was certified to have a psychiatric illness. But in 1999, he was sent back to prison for violating terms of his parole—he had become politically active again—and, after having his life sentence commuted, is still not due for release until 2024.

Perhaps no case today better illustrates Beijing’s aversion to granting medical parole to political prisoners than that of Hu Jia. He began his activism by railing against environmental degradation and the Chinese government’s slow response to AIDS, and assisted in campaigns to release political detainees. Hu was arrested in December 2007 following his video testimony at a European Parliament hearing at which he spoke out against human rights violations in China and the holding of the Olympic Games in Beijing. Hu was eventually sentenced in April 2008.

Chinese authorities have a credibility problem when making a case that Hu does not qualify for medical parole. His wife, Zeng Jinyan, an activist in her own right, contends that Hu’s cirrhosis developed after his hepatitis B went untreated when he was “disappeared” for 41 days in 2006, though authorities claimed Hu received medication during that period. In May 2009, Hu’s family filed the first medical parole application after Zeng visited him and found him thinner and weaker, partly due to resistance to his anti-viral drug, which he had stopped using earlier in the year. On March 30, 2010, Hu was admitted to the Beijing Prison Bureau’s hospital for tests to see if he had developed liver cancer. While officials and doctors said that no malignancy was found, test results were not released to the family, but instead (as in May 2009) simply passed along verbally.

Officials have poorly cloaked the political rationale for keeping Hu behind bars. In rejecting the recent request, officials said that releasing Hu on medical parole involved “other considerations” besides his health. In 2009, an official suggested there was a lack of “major political environment”—most likely, political intervention from above—for Hu to be paroled.

Hu has joined other political prisoners whose activism and subsequent incarceration have garnered enormous international support. Two weeks after he was sentenced, France made Hu an honorary citizen—the Dalai Lama was bestowed the honor the same day—and the European Parliament awarded Hu its Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought in December 2008. Hu, his sentence scheduled to expire in June 2011, is also a perennial favorite to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

Can Medical Parole Be Medicated?

Beijing should root the application of medical parole in the law and base decisions on which prisoners qualify for release on medical grounds. To legitimize standards for medical parole, authorities must make conditions inside prisons and the health status of detainees more transparent—but China seems to be going in the opposite direction. Despite Beijing’s openness, declared in 1994, to consider having the International Committee of the Red Cross visit prisons, the ICRC has not yet been given the opportunity. Refusing to release medical documentation to families of prisoners further inhibits any appearance that Chinese authorities handle medical parole in a valid way.

Though Beijing appears intractable about releasing political prisoners on medical parole, international actors should still encourage greater transparency and push for more information on prisoner health. Advocates can work through special bodies, including UN mechanisms, to urgently appeal for the release of ill prisoners, and names of prisoners who may be eligible for medical parole will no doubt continue to be raised within human rights dialogues.

Advocating for the medical parole of a political prisoner represents a two-pronged humanitarian appeal: clemency is sought to help save the life of a detainee already believed to be illegally imprisoned for exercising protected rights. Perhaps Chinese officials, now entrenched in a “stability-above-all-else” posture, will one day be secure enough to see it is more costly to their political legitimacy for citizens to suffer physically in prison than have them released into Chinese society, or not even incarcerated in the first place.