EVENTS

Dui Hua Executive Director John Kamm spent the week of June 5 in Washington DC holding meetings with senior American and Chinese officials who deal with human rights. Meetings were held with the National Security Council; the Department of State’s Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, Bureau of Consular Affairs, and Policy Planning Office; Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United States; Senate Foreign Relations Committee; and the Congressional Executive Commission on China.

Sessions were also held with leading legal scholars and academics, representatives of human rights groups, journalists, and family members and friends of past and current prisoners serving sentences for endangering state security. A highlight of Kamm’s week-long visit was a dinner with Jeff and Sandy Phan-Gillis; Sandy was tried for espionage and released from detention in Nanning on April 28, returning to the United States the same day.

Kamm was accompanied at several of his meetings by Dui Hua Program and Publications Associate Xandra Xiao.

Emerging Rights Policy

Features of the Trump administration’s China human rights policy are coming into focus. Kamm identified several features that will define the approach the administration takes towards addressing human rights in China.

Dialogue Mechanisms

As agreed to by President Trump and President Xi at the April summit in Mar-A-Lago, the two countries have agreed to establish four “comprehensive dialogue mechanisms (CDMs).” The mechanisms will replace the Strategic & Economic Dialogue (S&ED) agreed to in 2009 by President Obama and President Hu.

The four CMDs cover diplomacy and security, economics, law enforcement and cyber security, and social and people-to-people exchanges. In addition to replacing the S&ED, several stand-alone dialogues covering a plethora of issues will be folded into one or more of the CMDs. Some dialogues are expected to continue. The dialogue on the rights of the disabled — a session was held in Washington in May — is likely to continue.

Two of the existing dialogues, namely the human rights dialogue and the legal experts dialogue, will no longer take place. The annual human rights dialogue, started in 1991, was increasingly unsatisfying for officials in both Beijing and Washington to the extent that no dialogues took place in several years, including 2016. The Trump administration intends on raising human rights concerns in every CDM. As an example, the free flow of information, vital to successful business operations, will be raised in the economic CDM. Both individual cases and issues like the Foreign NGO Management Law will be discussed in the CDM framework.

The first CDM, the one devoted to diplomacy and security, will take place in Washington before the end of June. The Chinese delegation will be led by State Councilor Yang Jiechi and the American team will be led by Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis. Subsequent CDMs will alternate between Washington and Beijing.

Putting Americans First

The Trump administration will prioritize cases of prisoners who are either American citizens or who have strong connections to the United States. Examples of the latter might be Chinese citizens like Jiang Tianyong, whose wife lives in the United States, and Tashi Wangchuk, a Tibetan activist detained after giving an interview to The New York Times.

Trump administration officials point to two early successes of this policy: the rescue of Chen Guiqiu, wife of lawyer Xie Yang, and their two daughters (one of whom is an American citizen) from the clutches of Chinese agents in Thailand in March, and the April release and deportation of American businesswoman Sandy Phan-Gillis.

An issue of growing concern for the administration is the increased use, by Chinese police, of exit bans issued against American citizens. As many as 20 Americans are believed to be barred from leaving China. While several of the bans are related to ongoing commercial disputes, several appear to be related to investigations into alleged corruption activities on the part of relatives of the Americans living outside China. Placing an exit ban on the American citizen is seen by American officials as a way to pressure the relative living overseas to return to China.

Funding

Concern is widespread among human rights groups that President Trump’s large cuts to the Department of State’s budget for Fiscal Year 2018 will result in a sharp decline in funding of activities related to human rights in China. Shortly before Kamm arrived in Washington, the International Campaign for Tibet issued a statement decrying the “zeroing out” of funds for Tibetan programs in the FY18 budget.

Congressional staffers cautioned against jumping to conclusions. It is Congress that has the final say on budgets, and support is strong in both the House of Representatives and the Senate for funding human rights activities. As one experienced lobbyist put it, “No presidential budget has passed Congress in the form submitted to Congress in recent years.” At the end of the day, the Trump administration will likely acquiesce in the continued funding of China-related human rights activities.

The New Team

Three individuals have emerged as key players in the formation and implementation of the Trump administration’s China human rights policies.

United Nations Ambassador Nikki Haley: Known for her strong positions on civil rights while serving as governor of South Carolina, Haley criticized China and four other members of the UN Human Rights Council for their records on human rights in her first speech to the Council on June 6. Those countries have “clearly failed to live up to the highest standards of human rights,” a condition for membership in the Council.

Senior Director for Asia in the National Security Council Matt Pottinger: A journalist who lived in China and witnessed first hand how petitioners and protesters were treated by police, and a decorated war veteran, Pottinger has already made a name for himself by advocating on behalf of Chinese prisoners. He was active in securing the release and return of Sandy Phan-Gillis. Pottinger raised eyebrows in Beijing by meeting with the wives of imprisoned Chinese rights activists together with the wife of detained Taiwan activist Lee Ming-Che.

Acting Assistant Secretary of State Susan Thornton: An experienced foreign service officer with more than 20 years of experience in China, Thornton is familiar with all areas of US-China relations. She brings to human rights diplomacy a deep knowledge of where human rights fits into the overall relationship, and strives to strike a balance between human rights and other concerns. She reports to Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan, whom was confirmed by the Senate on May 24. Sullivan has a keen interest in promoting respect for human rights abroad.

Dui Hua recently received a response from its interlocutors that reveals that two female Falun Gong practitioners serving in Guangdong’s Women Prison received clemency. He Xinfang (何新芳) was granted her first sentence reduction of four months on February 19, 2016, after she was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment in March 2014. She is scheduled for release on August 1, 2018. Another Falun Gong prisoner Yuan Yujiao (袁玉娇) was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment in the same case as He and received her first sentence reduction of six months on November 17, 2016. Her sentence is now set to expire on March 19, 2019.

Featured: Phan-Gillis Case Highlights Deportation of Foreigners in China (May 18)

The adjudication of the Sandy Phan-Gillis case by the Nanning Intermediate People’s Court has drawn attention to the supplemental punishment of deportation under Chinese law. Ms. Phan-Gillis, a prominent American businesswoman, was convicted of espionage by the court on April 25, 2017. She was sentenced to three and one-half years in prison and deportation. She was deported on April 28 without serving her prison sentence.

Dui Hua Foundation Annual Report 2016 (May 23)

Previous Digest: May 2017

John Kamm Remembers

City of the Doomed (Part 2)

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s advocacy stories prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999.

To read part one click here.

An Artistic Troupe

We left the cell block and walked a few yards to a recently constructed prefab unit where, I was told, female artistic performers were held. There were 33 females in this “special unit.” I was led into the cell block. Women prisoners, behind a wire mesh, were doing laundry, hanging up their undergarments, and donning theatrical costumes. I wrote in my notebook, “The women were clearly chosen for their appearance.” They met my eyes with defiant looks. I had seen women behind glass windows and even in cages in Southeast Asia, but I never imagined I’d see something like this in China.

We left the women’s cellblock and headed for the theatrical performance at the prison’s auditorium. Our small party made up the entire audience. A special program was laid on by “The Xin-An Art Ensemble of Shanghai Tilanqiao Prison.” In all there were more than a dozen female performers and three male performers dressed up in traditional Han, Mongolian, Tibetan, and Uyghur garb. For an hour, we were treated to renditions of Leonard Bernstein’s Magnificent Seven, a tenor solo from an Italian opera, the theme from the movie Love Story and an assortment of ethnic song and dance routines.

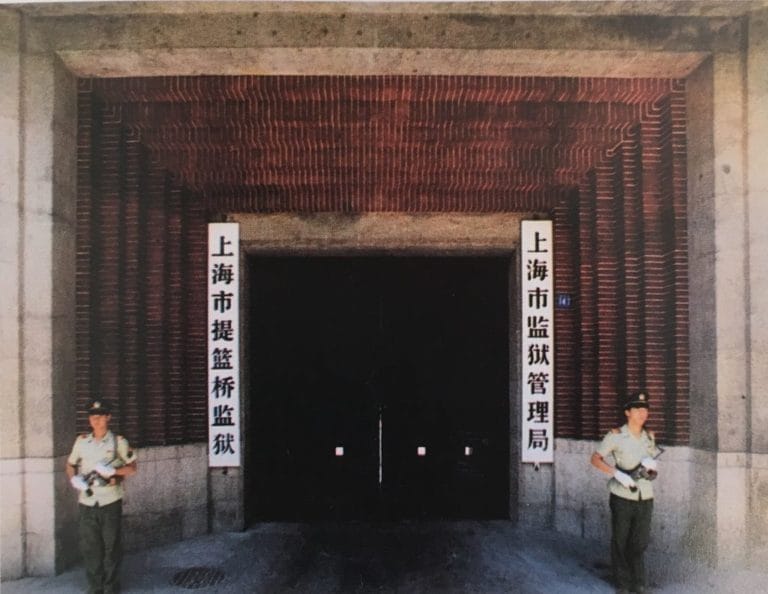

The last stop was the warden’s office, which was housed in the headquarters of the Shanghai Prison Bureau on the prison grounds. It was a squat red brick building constructed much like municipal administrative buildings throughout the British empire in the 1920s and 30s.

Political Prisoners in Tilanqiao

Warden Li and his colleagues asked about my impressions of Tilanqiao. I replied that I was impressed by how clean the prison looked. It certainly appeared that there was plentiful food. The staff looked to me to be professional. It was clear however that the prison was extremely overcrowded. I said that I was uncomfortable at times in both the male and female wards. I recommended that foreign guests not be allowed to get too close to inmates holding sharp scissors.

Warden Li thanked me for my comments and asked if I had any questions before we had dinner at a hairy crab restaurant. I said yes, I wanted to talk about people who might be imprisoned at Tilanqiao, and hear from the warden whatever information he could give me on them. Warden Li became somewhat uneasy at this, even more so when I pulled out my prisoner list.

|

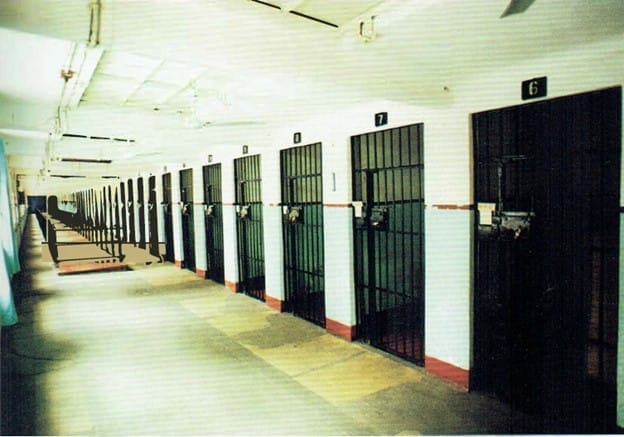

Inside a Tilanqiao prison block. Image Credit: Shanghai Prison Administration. |

I said I wanted to learn about someone on my prisoner lists who had been sent to Tilanqiao to serve a two-year sentence, Mr. Lin Hai, who had been released six months early and gone to the United States. Mr. Lin was said to be China’s first Internet dissident.

I remarked that I thought that only prisoners sentenced to 10 years or longer were housed at the prison. Warden Li replied that all Shanghai counterrevolutionaries were housed at Tilanqiao as part of a policy implemented in 1986 to segregate this special group of prisoners from the general population. Since then the number of counterrevolutionaries (and, after 1997, prisoners convicted of endangering state security) had been halved. It now stood at 17, half of whom were Taiwanese spies. I felt that segregating political prisoners from the general population was an enlightened policy; in some provinces, political prisoners in the general population are bullied by other prisoners, especially those serving time for violent crime. In fact, after his release, Lin revealed that he had not been mistreated, and had not been forced to do manual labor. He complained, however, about overcrowding, saying that he shared his small cell with one or at times two other prisoners.

Since 1986, sentence reductions for political prisoners had increased, but the rate of reduction was well below that for ordinary prisoners, Warden Li acknowledged.

I wondered if Warden Li was familiar with the name Yu Rong, a young man who had thrown 1,400 counterrevolutionary leaflets from the tops of downtown Shanghai buildings in 1990, a case that then-mayor Zhu Rongji dubbed the biggest case of counterrevolutionary incitement and propaganda in the city’s history. Warden Li was not familiar with the name. (In 2006 I learned that Yu Rong had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and was incarcerated in a psychiatric detention center, also known as Ankang.)

I asked about Tao Shanben, sentenced to life in prison for being a follower of the Gang of Four. Warden Li said there were no more Gang of Four elements in the Shanghai prison system.

Warden Li recognized the names Yao Kaiwen and Gao Xiaoliang as convicts who had tried to set up a counterrevolutionary group. Beyond that, he declined to say more. According to my notes, Yao, a school teacher, and Gao, a worker, had been detained in May 1993 for establishing “The Mainland Headquarters of the Democratic China Front.” They were subsequently sentenced to 10 years and nine years in prison, respectively. Gao received a sentence reduction after my visit, and was released in late 2001. Yao served his full term and was released in May 2003.

Li Junmin in The City of the Doomed

Sensing that the time for questions was running out, I moved on to my last two prisoners, Taiwanese spies Zhou Guogui and Li Junmin. I had received information on them from the MOJ in March 2000 at which time both were serving sentences in Tilanqiao.

Zhou was an elderly Hong Kong doctor who had been sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment in 1986 for spying for Taiwan. Because he suffered from a heart condition and high blood pressure, he was released on medical parole a few months before my visit.

Li Junmin was the most famous counterrevolutionary prisoner in Shanghai at the time. A Taiwanese intelligence officer, he was sentenced to life in prison for espionage in May 1982 and sent to Tilanqiao. While in Tilanqiao, he managed to send letters detailing conditions in the detention center in which he had been held prior to being sent to Tilanqiao. He sent the letters through prisoners who were about to be released. He also carried out “counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement” among other prisoners – “viciously attacking the Communist Party and seeking to overthrow China’s socialist system.”

Li was tried again for his new crimes, and the Shanghai Intermediate People’s Court sentenced him to death in December 1983. The Shanghai High People’s Court upheld the verdict and sent the case for final review to the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) in Beijing. Following a decision made during the Strike Hard Campaign of the summer of 1983, death sentences could be carried out after the provincial high court had rejected an appeal, with an important exception: death sentences for counterrevolution had to be reviewed and approved by the SPC in Beijing.

The SPC overturned the death sentence and passed a sentence of death with two-year reprieve in February 1984. In June 1986, this sentence was commuted to life in prison. Li’s life sentence was reduced to 18 years with seven years’ deprivation of political rights in June 1994. At the time of my visit to Tilanqiao, Li was scheduled to be released on December 20, 2012.

In contrast to his responses on other prisoners, Warden Li became quite animated when I mentioned Li Junmin’s name. In language reminiscent of how Democracy Wall prisoner Wei Jingsheng was described to me by MOJ officials in 1992, Li Junmin was “defiant, and resists reform. For a long time, he had nothing good to say about the Chinese government, but now he has acknowledged that recent developments might be good for the Chinese people,” said Warden Li. “He now wishes both China and Taiwan well.” Warden Li expressed the hope that, one day, there would be no prisoners serving sentences for counterrevolution or endangering state security in his prison, but for the foreseeable future, Li Junmin would stay in Tilanqiao.

A few months after my visit Li Junmin was given an eight-month sentence reduction. In 2003 he was granted a 14-month sentence reduction and this was followed in 2004 by a 12-month reduction. His sentence was commuted in December 2006. He returned to Taiwan to be greeted by his wife, who had never given up on Li Junmin despite being told by the Taiwan government that he was dead, and the son he had never known. Li Junmin had survived the City of the Doomed.