<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

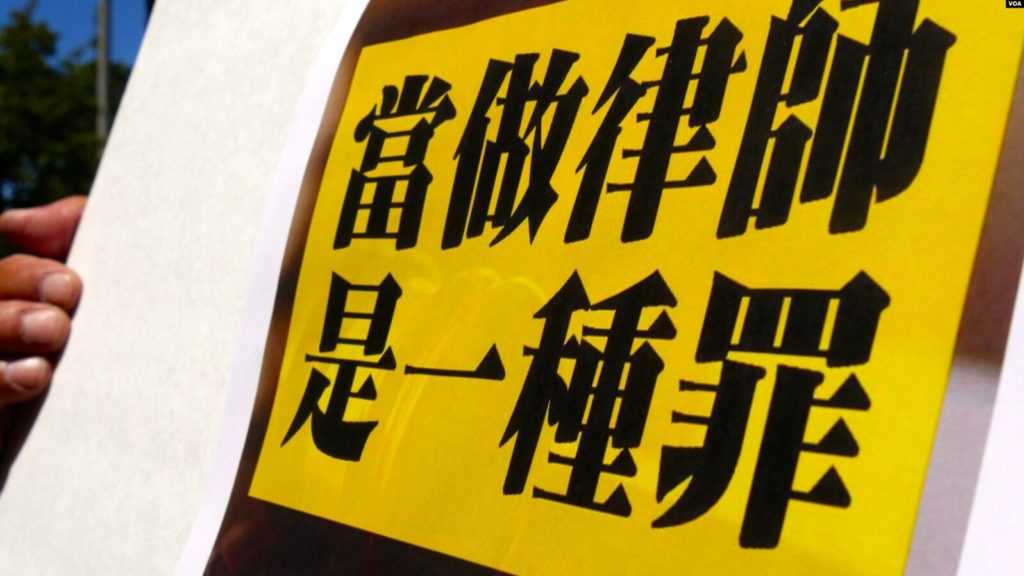

In the early morning hours of July 9, 2015, Chinese police moved against human rights lawyers, legal assistants, and rights activists across China, but mostly those living and working in Beijing. Over the coming days and weeks, an estimated 300 lawyers and activists were detained or had exit bans placed on them. Power was cut off at their residences. Many were stripped of their lawyers’ licenses, forcing law firms to close. Several of those detained were subsequently tried and convicted of state security offenses. A few are still in prison, including Wu Gan, an activist known as “Super Vulgar Butcher,” who was sentenced to eight years in prison for subversion in December 2017.

International reaction to what became known as the 709 Crackdown was sharply critical. Governments, bar associations, law schools, and experts from United Nations Special Procedures condemned the action, to no avail. In an early indication of China’s current policy of ignoring international opinion, Beijing has become defiant and increasingly oblivious to criticism. Even requests for information on the status of political prisoners are now considered assaults on China’s judicial sovereignty constituting interference in China’s internal affairs.

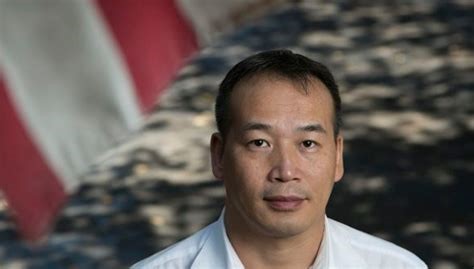

A Brave Lawyer

Prior to his detention by public security agents for inciting subversion, picking quarrels and provoking trouble, and embezzlement on July 12, 2015, and his subsequent departure from China in March 2016, Guilin-based lawyer and associate professor of law at the Guilin University of Electronic Science and Technology Chen Taihe was a well-known advocate of China adopting the jury trial system. He researched the jury system in the United Kingdom as a visiting professor and summarized his findings in an eloquent and well-argued book entitled The Most Common Right.

It is not known why Chen Taihe was detained. It might have been because of his friendship with leading rights lawyer, Li Heping, who was himself detained on July 10, 2015. Chen had called for his release. It could have been because of his extensive ties to the United States. It might have been because of his advocacy for China adopting the jury trial system. Or it might have been because of a vendetta against him by a Guilin official. China’s justice system is anything but transparent.

Chen Taihe’s activism brought him to the attention of the domestic security division of the public security bureau, a unit known as guo bao. They invited him “to drink tea” – a euphemism used for police questioning – on multiple occasions.

His successful law practice, which focused on civil and criminal litigations, brought him fame and wealth, enabling him to purchase three apartments in high-class developments. He gave that all away to find freedom for himself and his family in the United States, assisted by retired Judge Shackley Raffetto, the Dui Hua Foundation, and American diplomats in China. He is believed to be the only 709 lawyer to have successfully left China for the West with the permission of the domestic security bureau of the Chinese government.

Time on the Cross

Upon detention, Chen Taihe was placed in the Guilin Number Two Detention Center. He endured physical mistreatment, including being forced to squat for hours in a stress position, and threats from prisoners, one of whom had been sentenced to death. Chen was in a crowded cell with 12 other detainees; he was not given a bowl, spoons, and other necessary utensils to eat food and drink water for nearly three days.

Finally, on July 16, 2015, he was allowed a visit by a lawyer, who was a spy sent by the government. The second lawyer that visited him was Qin Yongpei. He posted Chen’s situation and mistreatment online after he interviewed Chen in a prison meeting room. (Lawyer Qin was detained in 2019; he has not been released and is currently under indictment for inciting subversion.) Chen was then moved to another detention center where his treatment slightly improved. A month after his detention, he was moved to a location outside the detention center and then on August 22, 2015, he was allowed to return home and placed under residential surveillance, but even then, he continued to be subjected to interrogation and threats by the police right up to the day he departed China.

While keeping the police advised of his whereabouts, he was allowed to move around Guilin and even to travel to other cities. The police monitored his communications and his movements. The family’s bank accounts were frozen, heaping misfortune on top of misery.

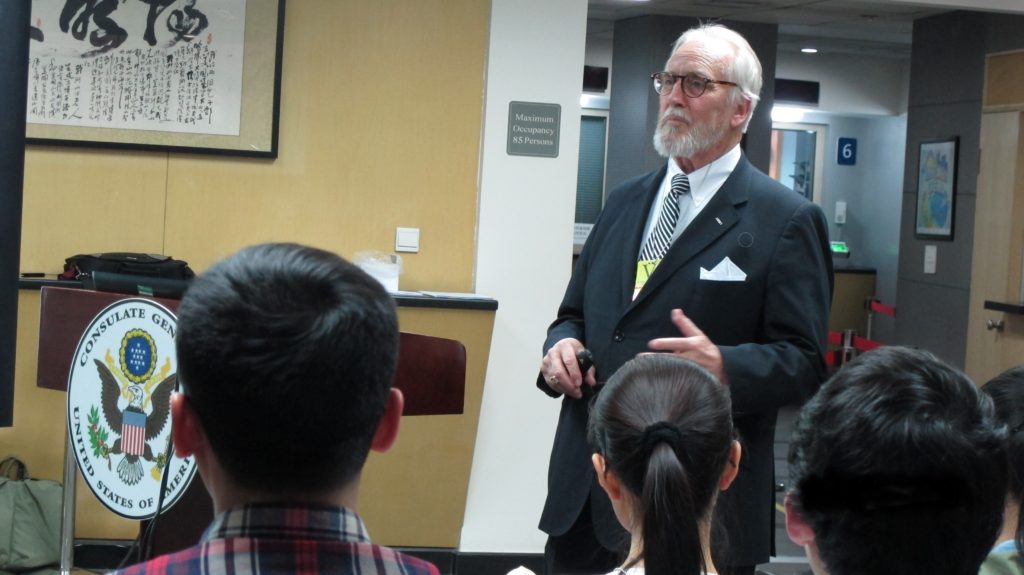

Judge Shackley Raffetto

On July 21, 2015, nine days after Chen Taihe’s detention, I received an email from Shackley F. Raffetto, a retired Hawaii state trial judge and US Navy judge who had befriended Chen Taihe following an introduction by a lawyer based at the US Embassy in Beijing. Judge Raffetto invited Chen and three other Chinese lawyers to visit Hawaii in September 2013. While there, the small group of Chinese lawyers observed a jury trial and were able to interview the jurors after the trial concluded. They met with the Chief Justice of the Hawaii Supreme Court as well as law professors and lawyers from firms involved in legal exchanges with lawyers in China.

Judge Raffetto had already lectured and conducted a US style jury trial moot program at two PRC law schools. In April 2014 he travelled to Beijing, at the invitation of the US Embassy, with the intention of providing the jury trial moot at a number of law schools that had requested the program. The first school at which the trial moot program would be presented was Chen Taihe’s law school. Chen had advised the Guilin police that he had invited Judge Raffetto to conduct the program at his university.

Upon arrival in Beijing, Judge Raffetto was told that the entire program had been cancelled. No explanation was given. Chen Taihe was ordered not to participate in the program. Judge Raffetto adjusted the program and proceeded to give lectures on the American justice system at law schools around China, arranged by the US government. Police tried to block people from attending his lecture in Beijing. They were admitted by a side door.

In July 2015, Judge Raffetto noticed that Chen Taihe’s name was on a list of lawyers and activists detained in the 709 crackdown drawn up by Amnesty International. He contacted the US Embassy in Beijing, the people with whom he had worked on programs, but never received a response. He then reached out to human rights groups, including Dui Hua, to see what could be done for his friend.

Role of China’s San Francisco Consulate

In my work on Chinese political prisoners, I have used different channels to submit lists and discuss cases. One of the most important channels has been the Chinese consulate general in San Francisco. I reached out to my point of contact, Consul Wang, and asked for a meeting to discuss Chen Taihe’s case. We agreed to meet on Monday, July 27, 2015, at the consulate on Laguna Street.

I submitted a detailed memo on what I knew about the case. I pointed out that Chen was the only law professor to have been detained in the 709 crackdown and pointed out that President Obama was also a law professor. Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, whose capital is Guilin, is the sister state of Montana, home state of US Ambassador Max Baucus. For these reasons, Chen Taihe’s case was now a high priority for the US government.

Wang took action. He impressed on his superiors in Beijing the importance of the case. A few weeks later Chen Taihe was moved out of the detention center and eventually placed under residential surveillance. Unfortunately, his ordeal was far from over.

Throughout my work on the case, I stayed in close touch with officers at the United States Department of State and the National Security Council in Washington as well as the US Embassy in Beijing. Washington-based officials were a source of good advice and assistance arranging Chen’s departure and providing limited financial support. Chen Taihe was well known to the Department of State prior to his detention in 2015. In both 2011 and 2012, Chen Taihe had participated in legal exchange programs and in 2012 he visited Washington DC at the invitation of the State Department’s International Visitor Leadership Program.

Ms. Jiang Jie Flees China, Arrives in US

While their loved ones are suffering in prison, families of political detainees suffer on the outside, often denied visitation rights and telephone calls, not knowing if their spouses are still alive. Sometimes, spouses are urged to divorce their partners so that their children can lead a “normal life,” free of stigma.

Jiang Jie, the wife of Chen Taihe, was interrogated by the police attached to the domestic security division (guo bao) of the Guilin public security bureau, and their apartment was searched on two occasions. The police told Jiang Jie, four months pregnant with the couple’s second child, that she was violating the one-child-per -family policy in force at the time. They tried to convince her to abort the baby. Jiang Jie refused.

Chen Taihe had a US visa, a J2, in his passport; this entitled Jiang Jie to a dependent visa in her passport. Despite limited English and not having friends or family in the United States, Jiang Jie decided to leave Guilin and fly to San Francisco. She purchased two separate tickets, one for her, one for her son, as close as possible to departure. She took these steps to throw the police off her scent. On August 3, she flew to Guangzhou, on the pretext of looking for a lawyer, and, on August 4, together with her son, she boarded a flight to Seoul. From there she flew to San Francisco, arriving on August 4, 2015.

Upon deplaning at the cavernous arrival hall at SFO, Jiang Jie and her son faced a stern Customs officer. He told her that her visa entitled her to enter the United States with her husband, not by herself. They were taken to a room where she had to deal with an unfriendly interpreter over the telephone. This person tried to convince her to return to China. Jiang Jie stood her ground and refused to be sent back.

Finally she was moved to another room where she was dealt with by a friendly immigration officer. He eventually allowed her to enter the United States after she told him where she planned to stay. It had been nearly 24 hours since she arrived at the airport.

Jiang Jie and son Zuoan went to Fremont where she rented a place to stay. After her husband was released from the detention center, he called her on her mobile. She was overjoyed to hear his voice. At the end of August, at the suggestion of an official at the American embassy in Beijing, she made contact with Dui Hua. We began to assist her. At the end of September, she contacted the legal aid center at the University of California Berkeley. They proved to be very helpful to her and her husband in starting a new life in the United States.

Trips to Guangzhou and Beijing

After his release from detention to residential surveillance, Chen Taihe was summoned every two weeks for interrogation by guo bao. These sessions took place either at the guo bao office or in a hotel. These were extremely stressful events during which Chen was threatened with rearrest.

The final straw was when the case of arrested lawyer Pu Zhiqiang was brought up in an interrogation session. Pu had been detained in May 2014 for creating a disturbance and inciting ethnic hatred by posting seven Weibo messages between 2011 and 2014. At the time of Chen Taihe’s interrogations in Guilin, Pu had yet to be brought to trial. One of his interrogators pointed out to Chen that Pu had only posted seven Weibo messages whereas Chen had posted thousands. (Pu was subsequently tried and given a three-year suspended sentence. He was stripped of his license to practice law.)

At around the same time, lawyer Bao Longjun’s son was arrested trying to leave the country for Myanmar and Hong Kong bookseller Gui Minhai was kidnapped in Thailand and taken back to China.

Fearing his rearrest was imminent and that he would die if he were put back in detention, Chen decided to leave China. He would travel to Guangzhou, site of a large US consulate. Not knowing that one cannot apply for political asylum at a consulate, Chen went to the consulate where he sought entry. He was turned away, and he made his way back to Guilin.

Chen then sought permission from guo bao to travel to Beijing. Permission was granted. The first trip was used to tie up loose ends of cases he was working on. The second trip, undertaken in February 2016, was to apply for a new visa to enter the United States. The visa was granted on February 24, 2016 whereupon Chen briefed American officers on what he had endured.

Airport Scenes: Guilin and San Francisco

All was ready. Chen Taihe went to Guilin Liangjiang International Airport to board a plane to Hong Kong where he was to board a plane to San Francisco. After checking in with his luggage on March 1, 2016, he approached immigration. They cleared him to leave, but after entering the departure area officers of wu jing, the people’s armed police deployed at the airport, stopped him and refused to let him board the flight. Chen called guo bao who intervened on his behalf. After half an hour wu jing relented and Chen was allowed to board the flight.

It was a nervous 320-mile flight to Hong Kong on a Chinese carrier through China airspace. After arrival at Hong Kong international airport, he boarded a flight to San Francisco.

Unlike his treatment at Guilin Airport and Jiang Jie’s treatment at SFO, Chen entered the United States without incident. At the arrival hall he was met by Jiang Jie, his oldest son, and me.

Doubtless exhausted, he nevertheless was upbeat and full of energy. He and his small family boarded a taxi for their small apartment in Fremont.

A New Life

After he arrived in the United States, Chen Taihe applied for political asylum through his Berkley-based legal aid team. Judge Shackley and I wrote letters supporting his application, which was eventually granted. It allowed him to not only stay in the United States but to seek employment as well.

Chen wanted to practice law but he needed the support of the Guilin Bar Association, issue a certificate of good standing which they refused to provide. Fortunately, the California Bar Association can grant permission to take the bar examination if the applicant is supported by letters from practicing lawyers. With the of his legal aid team, Chen Taihe gathered five support letters and sent them along. The California Bar Association accepted his application to take the bar examination.

Chen Taihe decided to put off taking the examination to make some money to support his family. He joined California’s largest landscaping firm working in the red-hot San Francisco Bay Area property market as a landscaping designer and project manager. Always good with his hands and with a keen eye for detail, Chen was an immediate success, his efforts praised by colleagues and customers alike. He eventually set up his own company.

Today, Chen Taihe, Jiang Jie and their three children (a daughter, Stephanie, was born in September 2021) are living the American dream. A successful businessman, Chen owns his own firm and his own home. He continues to fight for democracy and human rights in China by posting on social media, delivering a lecture at Hastings Law School where he was granted a position of visiting professor, and asking me to intervene on behalf of imprisoned lawyers and members of their families in China.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.