In 2005, Rebiya Kadeer – Uyghur entrepreneur and activist – had been given a rapturous welcome on her arrival in the United States. John Kamm recounts his contribution to Rebiya’s release, following her fall from grace from Chinese politics and subsequent arrest and imprisonment.

<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

The senior Chinese diplomat and I agreed to meet at the usual time and place: breakfast at 8:00 AM at the historic Mayflower Hotel, not far from the White House in Washington D.C. The date was May 19, 2005. It was a cool and cloudy day.

The Mayflower was the site of China’s first diplomatic presence in the United States after the two countries resumed contact in the early 1970s following many years of not talking to each other. For several months in 1973, the hotel housed China’s Liaison Office, the forerunner of its embassy. The establishment of the Liaison Office was the result of the Nixon-Kissinger foray into China in 1972.

While the Mayflower had a historic significance for Chinese officials, my interest in dining there was more prosaic. It offered outstanding breakfasts, including, among my favorites, eggs benedict and corned beef hash and eggs.

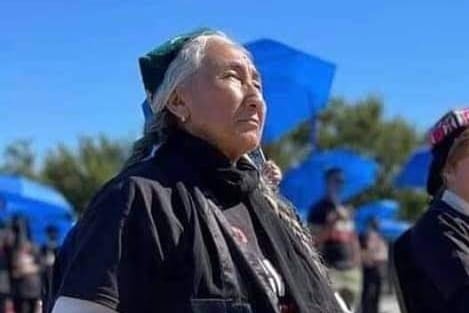

My guest arrived in a poorly tailored western suit, adorned with a scowl on his face. He sat down, and we exchanged pleasantries. The source of his displeasure soon became apparent: the March arrival in Washington of the Uyghur entrepreneur and activist Rebiya Kadeer. She had been given a rapturous welcome at Dulles Airport by members of her family, the Uyghur diaspora, and officials of the U.S. government. The welcoming ceremony featured a victory dance.

I had met with Rebiya and her family the day before my breakfast with the diplomat.

As was the custom when I met Chinese officials, I intended handing over a prisoner list. The official raised his hand as if to signal “Not now,” saying, “Before we get to that, you and I need to talk.”

The embassy official claimed that the reception given to Rebiya Kadeer violated an understanding between Washington and Beijing not to “hype” her arrival in the U.S. Specifically, it went against the tacit agreement between the U.S. ambassador Clark Randt to keep Rebiya quiet. There would be consequences, the diplomat threatened.

I said that I was confident that the State Department could take care of itself. “But what about you, Mr. Kamm? You have business in China. Can you take care of yourself?”

“What do you mean by that?”

His response was a sloppy smile and silence. The threat was clear.

I was not able to hand over my list.

A few days after this breakfast, I flew to Dallas Texas and resigned from the board of directors of an U.S. telecommunications company. Such was the end of my business career.

August 1999

On August 11, 1999, Rebiya Kadeer, a son, and her secretary, were taken into custody in Urumqi on the way to meet a U.S. congressional staff delegation at the Yindu Hotel, a luxury business hotel in the center of the city. She was carrying newspaper clippings that she hoped the delegation would give to her husband, Rouzi Sidik, in Washington D.C. Rebiya had earlier mailed him clippings from Urumqi, Kashgar, and Ili newspapers, as well as clippings from the Xinjiang Legal News. These newspapers were freely available and sold on the streets of Xinjiang’s cities.

In addition to the newspaper clippings, Rebiya was planning to hand over a list of Uyghur political prisoners, and a list of the victims of the killings in Ghuljia, the capital of Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, in 1997.

Rebiya was formally detained two days later and placed in the Liudaowan Detention Center where she would stay for more than 12 months. She later revealed, in an interview with American media, that, although she herself was not tortured, she could hear other detainees screaming from torture.

Rebiya was formally arrested on September 2, 1999, and subsequently tried and convicted by the Urumqi Intermediate People’s Court of illegally providing state secrets abroad, a crime of endangering state security. She was sentenced on March 10, 2000, to eight years in prison, and was given a supplemental sentence of two years deprivation of political rights. Rebiya appealed her eight-year sentence but in November 2000, the Xinjiang High People’s Court rejected her appeal and upheld the intermediate court’s sentence. She was sent to Xinjiang Women’s Prison to serve her sentence. Her sentence was due to expire on August 12, 2007.

When she was detained, the international media referred to Rebiya as a successful businesswoman. That was certainly the case. Starting as a seamstress sewing undergarments, she went on to build a vast business empire consisting of department stores and real estate in China and central Asia. She was to become one of the richest people in China, said to be the richest businesswoman in the country with assets worth hundreds of million renminbi. She served in high positions in industrial and commercial bodies in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

In addition to her business acumen, Rebiya was a philanthropist who invested in schools throughout Xinjiang. She was a political leader who served as a delegate to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (the top advisory body to the Communist Party) and a delegate to the National People’s Congress (NPC). She would criticize Chinese government policies and was an outspoken advocate for greater Uyghur autonomy. She founded the “Thousand Mother’s Movement” to promote job training and employment opportunities for Uyghur women.

In September 1995, Rebiya attended the United Nation’s Fourth World Conference on Women, held in Beijing. At that conference, Hilary Clinton delivered a speech titled “Women’s Rights are Human Rights.” Beijing was not happy with her remarks.

A year later, her husband Rouzi Sidik left China and applied for political asylum in the U.S., which was promptly granted (he had served time in prison for his political activities). At the same time Rebiya delivered a speech on the plight of Uyghurs to the NPC. She had torn up her approved speech and in response to these events, the Chinese government cancelled her official positions and seized her passport.

Dui Hua Gets Involved

In early 2000, I was asked by a member of the congressional delegation that went to Urumqi to help Rebiya get early release and better treatment.

The first thing I did was to seek out a trusted source of information and advice in the Chinese government. How is it possible, I asked, for clippings from freely available publications to be considered state secrets?

The answer: it is not the content of the clippings, but their choice. Why those clippings? Why those newspapers on those dates? What is the hidden message? These were grounds for suspicion in the eyes of the Chinese government.

I began raising Rebiya’s name in meetings with party and state officials. Dui Hua started including her name on prisoner lists submitted to Chinese government ministries. In all, Dui Hua submitted eight prisoner lists before 2004 and received more than 20 responses.

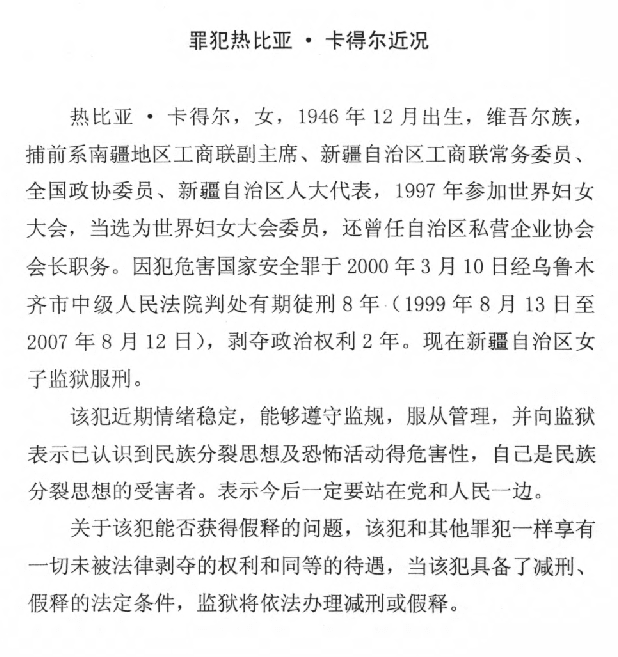

One response was especially significant. On September 10, 2003, while in Beijing, I met with Gong Xiaobing, the newly appointed Director General of the Ministry of Justice’s Bureau of International Cooperation. (I had faxed a request for information on Rebiya to the ministry two weeks earlier.) Mr. Gong gave me a detailed account of Rebiya behavior in Xinjiang Women’s Prison. The response stated that “the prisoner recognized the harmful nature of minority splittist ideology and terrorist activities” and went on to say that “from now on she would definitely stand on the side of the Party and the people.” This was a strong indication that Rebiya could be considered for clemency.

Response to Dui Hui by the Chinese government, September 2003 (translation)

Rebiya Kadeer, female, born in December 1946, Uyghur ethnicity, prior to arrest was vice-chairperson of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region’s Nanjiang District Industry and Commerce Association, a standing committee member of the Xinjiang Autonomous Region Industry and Commerce Association, a member of the C.P.P.C.C., and a representative from Xinjiang of the National People’s Congress. In 1997, she attended the World Conference on Women and was elected to be a committee member of the World Conference on Women. She has also held the position of president of the Autonomous Region Private Business and Industry Association. Sentenced on March 10, 2000, to eight years’ imprisonment (sentence to run from August 13, 1999, to August 12, 2007) with two years’ subsequent deprivation of political rights by the Urumqi Municipality Intermediate People’s Court for committing the crime of endangering state security. Currently serving her sentence in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region Women’s Prison.

Recently, this prisoner’s emotions have been stable, and she is able to respect prison regulations and obey supervision. She has expressed to prison officials that she recognizes the harmful nature of minority splittist ideology and terrorist activities, and that she herself is a victim of minority splittist ideology. She also said that from now on, she would definitely stand on the side of the Party and the people.

As for the question of whether or not this prisoner will be granted parole, this prisoner enjoys all the rights not otherwise deprived by law and exactly the same treatment as other prisoners. When this prisoner meets the legal requirements for sentence reduction or parole, the prison will handle these matters according to law.

On December 11, 2001, the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention ruled that Rebiya had been arbitrarily detained. In December 2002, the U.S. Department of State’s Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Rights, and Labor, Lorne Craner, went to Xinjiang to press for her release. On October 3, 2003, the U.S. Senate passed SR 230 calling on China to immediately and unconditionally release the Uyghur political prisoner Rebiya Kadeer.

At the same time, senior Chinese foreign affairs officials traveled to Urumqi to press local leaders to release Rebiya. They encountered resistance. It took a decision by the Standing Committee of the Politburo to order her release.

In September 2004, Rebiya was awarded the Rafto Prize in Bergen, Norway. Around the same time, she was nominated for the 2005 Nobel Peace Prize. Ultimately, the prize was jointly awarded to the International Atomic Energy Agency and its Director General Mohamed ElBaradei.

In response to intense media attention and international pressure, Rebiya was granted a one-year sentence reduction in March 2004. I was told that the original plan had been to release her immediately and allow her to join her family in the U.S. However, the U.S. sponsored a resolution criticizing China at the United Nations Human Rights Commission in Geneva and the plan was put on hold.

The U.S., citing progress on human rights in China, decided not to sponsor what China called an “anti-China resolution” in Geneva. Rebiya was granted medical parole. Accompanied by a U.S. diplomat, she boarded a flight to Chicago, thence to Washington D.C.

In March 2005, I was at Notre Dame University in South Bend, Indiana to deliver the third annual O’Grady Lecture. On March 16, I was enjoying a farewell dinner when I received a message from China: Rebiya Kadeer had been released and was flying to Chicago. Dui Hua released a press statement that attracted considerable media attention.

Prior to leaving China, Rebiya was warned: If you step out of line, your businesses will be ruined and your family will suffer. After her rapturous reception at Dulles International Airport and her interviews with foreign journalists, reaction by the Chinese government was swift. By mid-2006, her sons and other relatives and friends had been detained, and the process of seizing her assets begun. Initially, she was fined the equivalent of US$ 2.8 million. Eventually, the sum would amount to several hundred million dollars. (Levying massive fines and seizing assets has become a favorite technique of the central and local governments. It serves two purposes: bankrupt the opposition, including house churches, and funding local governments).

On January 6, 2006, the car in which Rebiya was travelling was rammed by a truck outside Washington D.C. The truck backed up and rammed her again. The license plates were traced to the Chinese embassy.

In early 2006, Rebiya went to Stanford University to deliver remarks to a small crowd in a seminar room. My son Jack was in the audience. She recognized him and expressed gratitude for what I had done to help her.

Developments Infuriate Beijing, Lead to Accusations

Dui Hua was by no means the only entity that worked hard to secure the release of Rebiya Kadeer. The U.S. government, other governments, and the United Nations all weighed in, in different ways at different times. Especially impactful were the written responses received by the U.S. Department of State. One response claimed that special dining and living arrangements had been made for the prisoner and that she was allowed a one-hour family visit once a month, extended upon request. It detailed a family visit from her nephew. The response said that she would be allowed to join her husband after her release.

What set Dui Hua’s interventions apart were its ability to wrest written responses from both the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Justice, and its being immediately notified of acts of clemency, which allowed Dui Hua to release its press statements.

On November 27, 2006, Rebiya Kadeer was elected President of the World Uyghur Congress (WUC). She was to serve until November 12, 2017.

The position gave her greater stature and more access to senior U.S. officials, notably President George W. Bush who met the WUC president in Prague on June 7, 2007. Bush welcomed Rebiya to the White House on July 20, 2008. Beijing lodged “strong representations” and registered “strong objections” to this interference in the internal affairs of China.

Neither President Barack Obama nor President Donald Trump ever met Rebiya . President Joe Biden, perhaps careful not to damage already strained US-China relations, has never met her either.

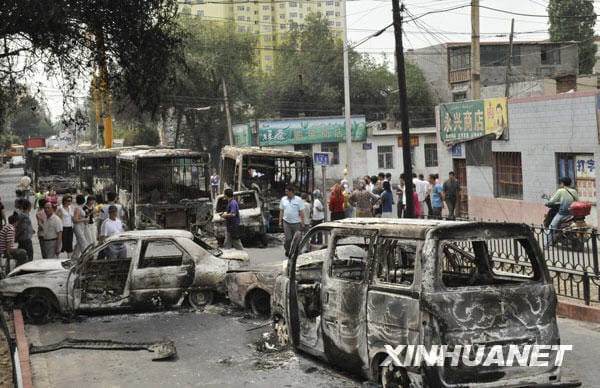

On the evening of June 26, 2009, Han Chinese men, enraged by the alleged rape of a Han Chinese woman by a Uyghur man, set upon Uyghur workers in Shaoguan, Guangdong Province, killing at least two of them. Days later, rioting broke out in Urumqi as Uyghurs attacked Han Chinese, killing around 200 and wounding many more. Despite offering no evidence to support its claim, Beijing blamed Rebiya and the WUC for instigating the riots. The Chinese government launched a campaign to label the WUC president a terrorist, and to further limit her international travel.

In July 2009, the Chinese Consulate in Melbourne Australia wrote to the organizers of the Melbourne International Film Festival, demanding that they cancel the showing of “The 10 Conditions of Love,” a documentary about Rebiya and the struggle of the Uyghur people against Chinese oppression. When the organizers refused, China pulled all seven Chinese films, including those from Hong Kong, from the festival. In Xinjiang, seven Uyghurs were arrested in December 2011 for possessing DVDs of the Rebiya documentary.

Over Chinese objections, Rebiya delivered remarks at the Fourth Session of the United Nations Forum on Minority Issues at the Human Rights Council in Geneva in November 2011.

Like the U.S., Japan issued visas to Rebiya in 2009, 2015, and 2019. She met with government officials, parliamentarians, and civic society leaders, and spoke at universities. Tokyo brushed off China’s protests. Surprisingly, Taiwan barred Rebiya from visiting the island in July 2010.

Although retired, Rebiya has remained active. In June 2024, she criticized the visit to Xinjiang of Hakan Fidan, Turkey’s foreign minister, claiming that he failed to condemn China’s treatment of the Uyghurs, who are a Turkic people. There is a large Uyghur exile community in Turkey.

In late 2024, the Urumqi city authorities razed the Rebiya Kadeer Trade Center, demolishing one of the last remaining reminders of her work in the city. What they haven’t been able to demolish are the memories and deep affection the Uyghur people have for Rebiya Kadeer.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.