<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

When I was president of the American Chamber of Commerce in 1990, I testified three times to the United States Congress as it was debating whether or not to renew China’s Most Favored Nation (MFN) tariff status. I presented what became known as the “Hong Kong argument”: Hong Kong, years away from being returned to China, would suffer disproportionately by removing China’s MFN. In one notable exchange between myself and Congressman Steve Solarz on May 16, 1990, I was asked whether I was advocating a “Hong Kong uber alles” policy. I reminded the congressman of the biblical story of Sodom and Gomorrah in which God spared the cities, both thoroughly evil, to spare the lives of a few good individuals.

In his decision to renew China’s MFN, President George H.W. Bush referenced the Hong Kong argument. This marked the first time in American history that the United States took into account Hong Kong’s interests when making a major foreign policy decision. My work received wide-spread acclaim in Hong Kong. A headline on the front page of USA Today referred to me as a “Hero in Hong Kong.”

Prior to my May 1990 testimonies I intervened on behalf of a young June 4 protester at a banquet hosted by senior Chinese official Zhou Nan in Hong Kong. After my testimony, the protester was released. I began to think I could use my vocal support for renewing China’s MFN to secure the release and better treatment of political prisoners. I decided to testify on two occasions in 1991.

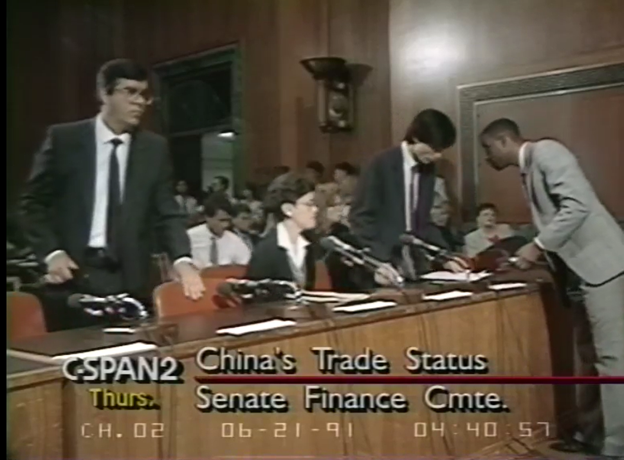

For my 1991 testimonies, I prepared what came to be known as the Guangdong argument. I decided to explore whether or not there was a correlation between a province’s human rights record and its dependence on trade with the United States. Guangdong’s main export market was the United States, and most Americans of Chinese descent traced their roots to the province. The plan was to gather evidence and make a report to the Senate Finance Committee hearing on June 20.

Five Trips to Guangzhou

I made five trips to Guangzhou from February to June 1991. I met with former political and religious prisoners including Li Zhengtian (member of the Li Yizhe group and honorary advisor to the Guangzhou Student Federation, a leader of the June 4 protests), Father Tan Tiande, an underground Catholic church leader who spent decades in prison as a counterrevolutionary), and Pastor Samuel Lamb (a leader in the house church movement who, like Father Tan, had spent more than 20 years in prison for counterrevolution).

On these trips I also met with senior officials of the Guangdong and Guangzhou governments, including a vice-governor, a vice-chairman of the Foreign Economic and Trade Commission, a vice-chairman of the local branch of the China Council for the Promotion on International Trade (CCPIT), the bishop of the official Catholic Church who I pressed to end the harassment of Father Tan, and officials of the Guangdong Province Prison Bureau, and the Guangzhou Public Security Bureau.

Prior to my last trip to Guangzhou prior to my testimony, I flew to Beijing for a series of meetings with Chinese government officials. My host was a vice-chairman of the CCPIT. They arranged meetings with a vice president of the Supreme People’s Court during which I pressed for the release of the Li brothers (Li Lin and Li Zhi), Hong Kong Trade Representative Lo Haixing, and two individuals accused of helping dissidents leave China as a part of Operation Yellow Bird. (All were eventually released early).

I also met with the State Council to review moves in Washington to strip China of its trade privileges. Everyone I met with were afraid that China would lose MFN. They were motivated to assist me.

Prison Exports

A goal of the trip to Beijing was to get approval to visit a Chinese prison in Guangdong. In addition to getting information on how June 4 counterrevolutionaries and hooligans were being treated, I wanted to look into whether or not Chinese prisons were exporting products to the United States, a hot issue in Washington. Vice Chairman Xie of the CCPIT promised to assist. Not all Chinese prisons were open to foreigners. He said he’d ask the Guangzhou branch to identify a prison I could visit. They would meet me at Guangzhou Bai Yun Airport the next day.

I flew down to Guangzhou on Wednesday, June 12, and was met by the CCPIT officer who would accompany on the prison visit. The young man informed me that we would visit the Shijing Juvenile Reformatory the next morning.

After settling into my room, I was joined for lunch by a colleague from the Occidental Chemical Hong Kong office as well as the Guangzhou office manager. After lunch we visited Li Zhengtian’s art gallery in the Novotel Hotel.

At nine AM the next morning, my CCPIT handler met me and my Hong Kong colleague at the front door of the Garden Hotel. We drove for around 30 minutes to the Guangdong Provincial Juvenile Reformatory, commonly referred to as Shijing Juvenile Reformatory, in Baiyun District, where we were met at the entrance by the reformatory’s warden. Shijing was a facility open to foreigners, and quite a few had visited since the reformatory was founded in 1958. Senior leaders from Beijing had also visited, and we were shown a photograph of Qiao Shi, a member of the Politburo when he visited in 1985. We were ushered into the main office where we listened to a taped message in English. The warden then launched into a “brief introduction” to his “model reformatory.”

The Shijing Juvenile Reformatory was, and remains, the only juvenile reformatory in Guangdong Province. It houses all juveniles from age 14 (the current age of criminal responsibility) to 18 convicted by courts in Guangdong. It is administered by the provincial justice bureau. Juveniles who commit offenses that do not rise to the level of crimes are housed in work-study schools under the watchful eye of public security bureaus. The longest sentence in the juvenile reformatory was three years. In 1991 there were more than 1,700 male juveniles in Shijing, and 31 females. A contingent of 240 officers made up the staff.

Most of the juveniles in the reformatory had been convicted of theft and robbery, but there were some who had been convicted of more serious crimes like murder, rape, wounding, and arson. Juveniles were housed according to their crimes in 10 separate dormitories. Girls were housed in their own dormitory.

Hooligans

I asked the warden if any of the juveniles had been convicted of crimes of counterrevolution committed during the May-June 1989 protests. He replied no, but some inmates had been convicted of hooliganism. One youth had stolen RMB 400 from the warden’s office.

There was a recidivism rate of 10 percent for youth who passed through the reformatory, relatively high for China. In a typical year, 70 percent of inmates were rewarded points for good behavior and 17 percent received sentence reductions or parole. If inmates misbehaved, there were five levels of punishment. They would first undertake self-criticism. The next step was a warning, after which the juvenile would be written up. Especially serious offenders were shackled and finally, their sentences could be extended. The purpose of incarceration was to reform the juveniles so that they would become “useful citizens.” Strict but fair management was practiced, the warden assured us.

Each juvenile was given 40 catties of rice a month, RMB 50 worth of other foodstuffs, and RMB 3 spending money. The whole reformatory consumed 20,000 catties of fish every month. (One cattie is equivalent to 600 grams). Inmates were allowed to watch three hours of television a week, and two movies a month. They were permitted monthly visits by family members.

We then toured the facility, a large area of several hectares surrounded by brick walls topped with wire. It was a barren, hardscrabble place. Vegetation was sparse, common to this part of Guangzhou. The workshops and dormitories were connected by concrete paths. It had rained recently, and mud was everywhere. Potted plants lined the walkways.

After visiting the girls’ dormitory, we toured a workshop where boys were assembling radios for the Guangzhou Number Two Radio Factory. The juveniles were seated on benches. Each had a name plate with the length of their sentence. They did not make eye contact with the visitors. I was told that there were also workshops making garments and spare parts for adult prisoner factories managed by the prison bureau.

The warden denied that any products were manufactured for export. “The quality is too low, too simple,” he explained.

After our visit, we were driven back to the city where we were hosted to lunch by a CCPIT vice chairman. I returned to Hong Kong on the late afternoon train and ate dinner on board for RMB45.

Progress but Setbacks

There were large influxes of juvenile offenders into the reformatory in the early 2000s. The facility maxed out at 4,000 inmates, resulting in serious overcrowding. A new reformatory was constructed. Recent photos show bright, multistoried buildings with juveniles working on arts and crafts.

My visit to the Shijing Reformatory was my first visit to a Chinese carceral facility, and it touched off an interest in juvenile justice reform. I subsequently visited a juvenile reformatory in Beijing and a juvenile camp on one of Hong Kong’s offshore islands. In 2008, Dui Hua began a series of five juvenile justice exchanges with China’s Supreme People’s Court. We have contributed to meaningful reforms, but deep issues remain and are poised to worsen. Effective March 1, 2021, the age of criminal responsibility will drop from 14 to 12.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.