<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

On many visits to Beijing, I came to know ambassadors from several countries in addition to the U.S. ambassador. Among the best friends I made were Norwegian Ambassador Svein Sæther, Swedish Ambassador Börje Ljunggren, and Italian Ambassador Massimo Iannucci.

I first met Massimo Iannucci in the early 1990s when he was Minister Counselor at the Italian Embassy in Beijing and I was working on the cases of imprisoned Catholic clergy. He and his wife hosted me for dinner at his residence, the home of a Qing Dynasty official on the outskirts of Beijing. They hired a chef who could prepare both Chinese and Italian cuisine. His wine cellar was well stocked.

After his stint as Minister Counselor in Beijing, Massimo Iannucci returned to Rome where he took up the position of Director General of the Asia Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation (MFA). While serving as director general, he also held the position of Italy’s Special Envoy to Afghanistan and Pakistan.

As Director General of the Asia Department, Massimo Iannucci hosted me on two visits to Rome in 2008 and 2009, respectively. If the trip to Hubei was a low point of my human rights work, the visits to Italy’s capital were high points, involving interactions between me and the MFA, parliament, the Holy See, and the Chinese Embassy.

Rome, 2008

I arrived in Rome on a flight from Zurich on the evening of October 4, 2008. I took a cab to the Rome Marriott Grand Hotel Flora, which boasted an exceptional restaurant, among other amenities. The hotel is near the Villa Borghese Gardens, enabling me to take morning walks.

The next day, I attended mass at the Basilica of Saint Paul. That evening, I dined with Iannucci and his wife, Carla, at their home.

At 9 AM on October 6, I was picked up at my hotel by an MFA official. Together we drove to the ministry’s headquarters, housed in the grand Palazzo della Farnesina. The building was constructed during the years Benito Mussolini ran Italy as a fascist dictator. Meetings took place with Director General (DG) Iannucci and senior colleagues, the ministry’s Chief of Cabinet, and the Vice Chairman of the Parliamentary Foreign Affairs Committee. Lunch was hosted by DG Iannucci at the ministry’s club.

In the late afternoon, I met with Monsignors Pietro Parolin and Rota Graziosi of the Holy See’s office of the Secretary of State in Vatican City.

Rome was the last stop on a five-week trip around the world. I flew back to the United States on October 7. Upon my return, I hosted Dui Hua’s first juvenile justice delegation from China’s Supreme People’s Court. Together we traveled across the country, visiting juvenile courts and detention facilities, as well as meeting with key figures involved in juvenile justice reform in the United States, including Justice Arthur Kennedy.

Rome, 2009

The purpose of the 2008 visit to Rome was to prepare for a talk there the following year. At my meetings with the MFA, and in subsequent communications, agreement was reached for me to make a presentation to an audience of Italian diplomats, think-tank representatives, and Italian scholars. The focus of the presentation would be human rights dialogues with China. A representative of the Chinese government would be invited to attend. As part of this agreement, the Italian government committed to giving Dui Hua a small grant to defray expenses.

On December 10, I was driven to the MFA’s headquarters. The program began with remarks by DG Iannucci followed by a statement by the Chinese ambassador to Italy, Sun Yuxi. Ambassador Sun’s remarks marked one of a few times that a Chinese official has spoken about Dui Hua’s dialogue with the Chinese government at a public meeting.

Here is what he said: “Under the leadership of Chairman Kamm, the Dui Hua Foundation has made great achievements in the field of international human rights promotion in just 10 years. It cooperated closely with the Chinese government and relevant institutions. And has established an unobstructed channel for exchanges between China and the West in the legal field. The Chinese government is committed to promotion and protection of human rights and is open to dialogue and exchanges with non-governmental organizations. It is hoped that the Foundation will achieve new results in 2010.”

Immediately after, Ambassador Sun left the meeting. He had been sent a copy of my presentation beforehand and was taking no chances on being in the room when I voiced criticisms of the human rights dialogues.

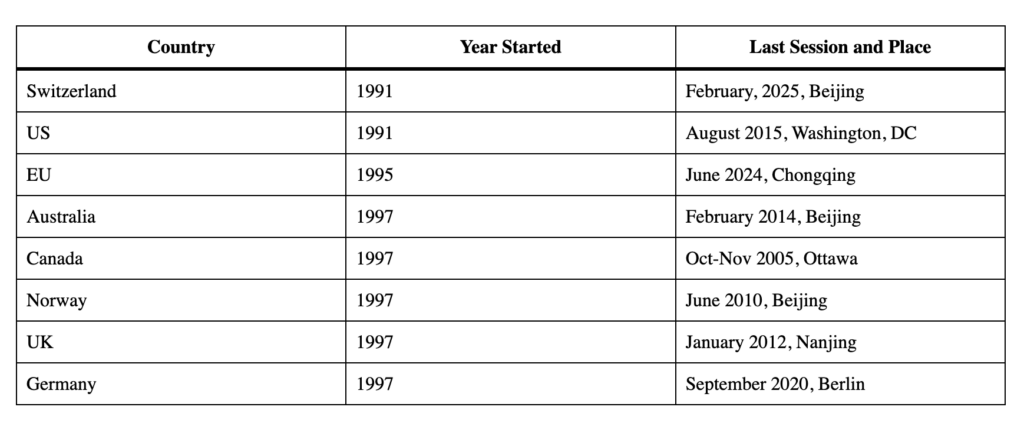

Human Rights Dialogues between China and Foreign Governments. Compiled by Dui Hua, 2025.

In my presentation to the audience of diplomats and others, I reviewed the status of human rights dialogues between China and foreign governments. At the time, there were seven such dialogues. (Canada, the eighth dialogue, was suspended by Ottawa in 2005. Japan claimed to have a human rights dialogue, but this claim was disputed by Beijing.) In 2024, only one dialogue took place, that of the European Union (EU) in Chongqing. Immediately prior to the dialogue, diplomats were permitted to travel to Tibet. Aside from a brief statement, the EU has been silent on what took place during the discussions. It is believed that the EU raised the names of individuals subjected to coercive measures. It is not known whether a list was handed over. The latest human rights dialogue between China and a foreign country – Switzerland — took place in Beijing in February 2025.

Meetings at the Vatican

During my visits to Rome in 2008 and 2009, I met with senior Roman Catholic clergy charged with handling relations between the Holy See and China, including Under Secretary of State for Relations with States Pietro Parolin, his successor Ettore Pietro Balestrero, and Archbishop Claudio Maria Celli. Archbishop Celli, was, for more than two decades, charged with overseeing negotiations between China and the Holy See. Those negotiations bore fruit in 2018 when, on September 22, a provisional agreement was reached governing the appointment of bishops. This so-called “secret agreement” has been renewed twice, most recently in 2024 for a four-year period.

On December 11, 2009, I set out from my hotel for the long walk to Vatican City. On my way to Saint Peter’s Square, I passed by the Embassy of the Republic of China (ROC) to the Holy See. Then, as now, this embassy was the ROC’s only embassy in Europe. (The office occupies the top floor in the same building as the embassies of Canada and Malaysia.) It is staffed by diplomats who handle interactions between the republic and European countries. Meetings with the Italian MFA are frequent.

I arrived at the Porta Sant’ Anna where I presented my credentials to the Swiss Guards guarding the gate. In short order, a priest came down to escort me to the meeting with Archbishop Celli. Joining us was an officer from the MFA.

My meetings with Celli and other senior prelates focused on the situations of imprisoned Catholics in China. As mentioned above, my work on these cases began in the early 1990s and was well known to the Holy See.

I was especially concerned with the plight of Bishop James Su Zhimin (苏志民), the head of the underground Bishops Conference, who had been taken into custody in 1997 after he met with a visiting U.S. congressman. He had been “disappeared,” apparently into an “Old People’s Home” in Baoding that was run by the local Religious Affairs Bureau.

I wondered if the Holy See had compiled a list of imprisoned clergy and lay leaders in China but was told that such a list was not kept. A prelate half-jokingly said that the Holy See didn’t want to interfere with their decision, including the decision to embrace martyrdom. (In fact, over the years, many Catholic priests have chosen death rather than renounce their faith.) Eventually, while gazing down on Saint Peter’s Square, a young priest unexpectedly slipped me a list of names. It was virtually identical to the lists I had worked on with Father Politi in Hong Kong.

My trips to Rome in 2008 and 2009 took place during the papacy of Benedict XVI. Both had been facilitated by the Vatican’s office in Hong Kong. Benedict was succeeded by Pope Francis upon the abdication of Benedict in 2013. Pope Benedict was more critical of China’s policy towards Catholics than Pope Francis under whose papacy an agreement with China on the appointment of bishops was negotiated. That agreement is said to have been criticized by Pope Benedict as well as Hong Kong Bishop Joseph Zen Ze-kiun (陈日君). Zen’s criticisms of the Holy See’s engagement with China came up during my visits to the Holy See, when senior clerics voiced frustration at his stance.

To show his backing for Zen, Pope Benedict insisted that Zen be invited to his funeral in 2023. Now a cardinal, Zen was detained in May 2022 due to his support for democracy in Hong Kong. Accused of colluding with foreign forces, Zen was later released on bail and has yet to be charged. Authorities confiscated his passport, but Zen was allowed to attend Pope Benedict’s funeral.

On my visits to Rome, I took the opportunity to do some sightseeing and Christmas shopping. I was given a private tour of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel, the Raphael Rooms and the Gallery of Maps which features a detailed map of Italy by Dante. To my surprise, those who lived in the Vatican apartments rarely ventured out to dine in restaurants nearby. They lived a cloistered life. I was under no such self-imposed culinary restriction. I dined at some of the best restaurants in the city before returning to the United States.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.