Download & read this story as a PDF

I

n the summer of 1989, I was a vice president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong (AmCham), in line to become president in 1990. I had overseen the chamber’s committees and was popular among the smaller members. I was unpopular with larger members, however, mostly on account of my pushing through a resolution condemning the killings in Beijing and other cities in June 1989.

When it came time for the nominating committee to appoint the next president, a meeting was held at which a former president of AmCham claimed that, if I were to be the next president, the Hong Kong government would be unhappy and would have nothing to do with the chamber. When it came time to vote, the nominating committee chose someone else to be president, leaving me in second place.

When the soon-to-be president called his boss in New York to give him the good news, he got an unexpected response: “You can be president of AmCham, or you can work for me. Those are your options. Your choice.” The fellow chose to keep his job — so I became the chamber’s president, by default, in 1990.

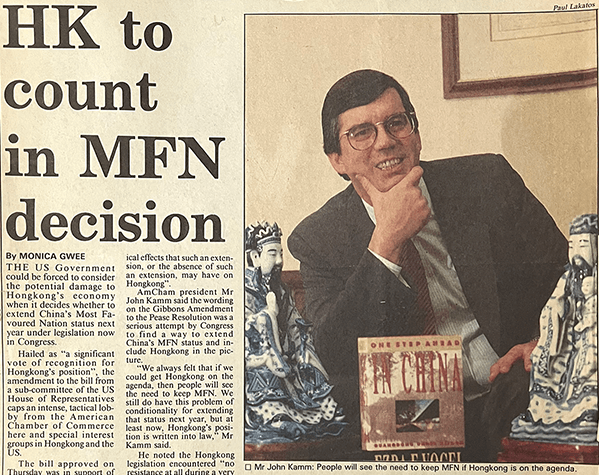

I began speaking out against Beijing’s actions, and my speeches were well-covered in Hong Kong media. It was an active year: during my tenure, I doubled chamber dues without losing members, shepherded the first woman to become a chamber vice president, and planned delegations to Mongolia and Myanmar (I had led a delegation to Laos in 1989). The joke around town was that I was the first AmCham president to have a foreign policy.

One day in March 1990, I was driving to work when I heard on the radio that Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell (D-Maine) and a junior member of the House of Representatives, Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi (D-Ca), would introduce resolutions to strip China of its Most Favored Nation (MFN) trading status. Although few in the colony were concerned that they would succeed in their efforts, I sensed the danger and began making preparations.

I assembled a “Council of War” and began planning to form a delegation to go to Washington. The team raised more than $100,000. One of the Council members, the local manager of a prominent lobbying firm, offered its services at a discounted rate. Another, the local representative of an American airline, gave us a break on the plane tickets.

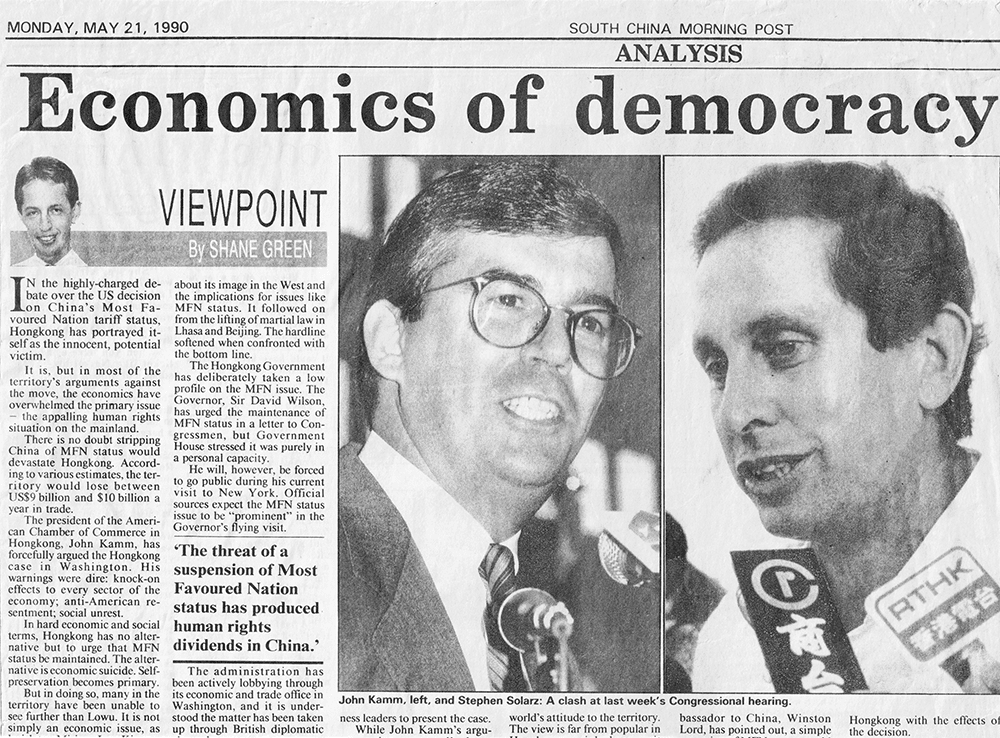

In April 1990, the chamber was advised that a hearing on “Most Favored Nation Status for the People’s Republic of China” would be held in Washington on May 16, 1990. The hearing would be jointly held by three subcommittees of the House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs: Human Rights and International Organizations, chaired by Gus Yatron (D-Pennsylvania), Asian and Pacific Affairs, chaired by Stephen Solarz (D-New York), and International Economic Policy and Trade, chaired by Sam Gejdenson (D-Connecticut). (The House Ways and Means Committee has jurisdiction over trade matters, including granting MFN to foreign countries, but Mr. Solarz decided to move forward regardless.)

I was contacted by Richard Bush — then a staff consultant to Mr. Solarz, now a widely recognized expert on US-China-Taiwan relations — and invited to testify at the hearing. Fools rush in where angels fear to tread. I readily accepted Mr. Bush’s invitation, even though I had never testified to Congress. In fact, AmCham had never testified to Congress, either.

A Novel Strategy

I hit upon an unusual strategy. Instead of avoiding human rights as businesspeople are inclined to do, I would embrace human rights. To do so, I needed to get evidence that businesspeople could do business and advocate for human rights at the same time.

In late April 1990, I led a delegation to Qingdao 青岛, in Shandong Province 山东省. I had been negotiating a joint venture with the Qingdao Sodium Silicate Factory and was familiar with the city’s leaders, including deputy party secretary Yu Zhengsheng 俞正声 (who later became a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, China’s highest political body, as well as a chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Congress).

While in Qingdao, I met with the local chamber of commerce. I was asked to be its honorary chairman, but I turned down the offer. Qingdao courts had handed down some of the longest sentences to June 4 protesters, including an eighteen-year prison sentence for counterrevolutionary incitement and propaganda for marine biologist and student leader Chen Lantao 陈兰涛. Under the circumstances, I couldn’t associate myself with state organizations in the city. To my surprise, the chamber officials said they understood, and asked me for the names of protesters who had been given long sentences.

Another highlight of my visit to Qingdao was accepting an honorary professorship at Qingdao University. In my acceptance speech at the conferral ceremony, I spoke of the relationship between MFN and human rights. After my remarks, a professor approached me. She knew Chen Lantao’s family and offered to help. (After many interventions, Chen was released in 2000, seven years early.)

I returned to Hong Kong on April 28. I gave two press conferences on the visit to Qingdao and the MFN state of play, met three times with the MFN War Council to make preparations for the chamber’s delegation to Washington, and met with a Chinese official who would later become an important source of information on political prisoners. I also dined with Hong Kong Governor Murray MacLehose on May 4, 1990, and met separately with Hong Kong’s Financial Secretary Piers Jacobs.

On May 9, AmCham’s leadership joined me at a banquet hosted by the Director of the Xinhua News Agency, China’s de facto embassy in Hong Kong, Zhou Nan 周南. I interrupted his toast to urge him to help secure the release of Hong Kong student Yao Yongzhan 姚勇战 from detention in Shanghai. Zhou was furious. Many of my AmCham colleagues were outraged — but shortly after I returned to Hong Kong after testifying to Congress, Yao was released.

The day after the dinner with Zhou Nan, I flew to Seoul on business, and on May 12 I continued my business trip in Tokyo. On Sunday, May 13, I holed up in my room at the Okura Hotel. Fortified by a dinner of sushi and a bottle of sake, I wrote my testimony for the May 16 hearing. I flew to Newark on May 14 and immediately took the train down to Washington, DC, where I checked into the Marriott Hotel.

On the long flight to Newark, I went over in my mind what questions House members might ask me after I finished my testimony. One in particular haunted me. I called my mother in Florida and asked her this question: what does the Bible tell us about a situation in which a majority of city residents are evil, but a small minority are without sin — should the city be spared? She was quick to reply: in the Book of Genesis, Abraham negotiates with the Lord to spare the lives of a small number of good people in Sodom, even though the overwhelming majority of residents were evil and worthy of death.

May 15 was full of meetings, many arranged by our lobbyists Hal Furman and Rick Spees. AmCham vice president Jeff Muir accompanied me on my meetings while other AmCham delegates fanned out to meet members of Congress and their staff. Jeff and I met with senior staff of Senators Bradley, Gordon, Lugar, and Simpson. We also huddled with the leadership of the National Council for US-China Trade and the Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office.

Words of Advice

One meeting stands out. We met for lunch at the office of leading law firm Jones Day, which had recently brought on board retired Senator Charles “Mac” Mathias (R-Maryland). Mathias gave me good advice on how to behave when testifying: “Whatever is said to you by a member, don’t overreact. Don’t get angry, and make sure to humbly respond. Coming from Hong Kong, you understand the importance of ‘face.’ Never make a member lose face.”

We arrived early at Rayburn House Office Building and settled into seats behind the front row in Room 2172. The hearing began at 9:40 a.m. The order of the witnesses was former ambassador to China Winston Lord, followed by advocates for Tiananmen Square victims and human rights NGO representatives, followed by US-China relations and trade leaders, and then business community representatives, of whom we were three.

Ambassador Lord, a Chinese student leader, and the Washington head of Human Rights Watch were given pride of place, and they delivered powerful testimonies in favor of sanctioning the Chinese government. David Lampton of the National Committee on US-China Relations and Roger Sullivan of the National Council for US-China Trade represented the establishment view that no sanctions should be imposed on account of China’s rights abuses. Now it was the turn of the businessmen.

By now, the hearing had dragged on for several hours, and I grew fearful that I would miss my flight to Dallas, headquarters of Occidental Chemical. Most of the members of the subcommittees had departed, including Congresswoman Pelosi, leaving Congressman Solarz and Congressman Chris Smith (R-New Jersey) on the podium. Smith represented a district adjacent to the district on the Jersey shore where I had grown up.

I took my seat at the witness table and tried my hand at “soaring oratory”: I spoke of the people of Hong Kong and their support for the pro-democracy movement in China. “Who knows better than the people of Hong Kong how bad the situation is? We are on the front lines. There are young Hong Kong people in Chinese jails. I take the opportunity to call once more for China’s leaders to release them to their families in Hong Kong. We, the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong, will continue to speak out and work as hard as we can to realize their freedom.”

I then made a fateful promise: “Whatever capital we might earn by fighting further sanctions, we will gladly spend in the effort to free all Chinese prisoners of conscience.” In the thirty-three years since I made that promise, I have tried my best to honor it.

Meeting Nancy Pelosi

C-SPAN was a fledgling network that broadcast political events, hearings, and votes in Congress. My testimony was beamed into offices all over Capitol Hill. It caused quite a commotion. Congresswoman Pelosi scurried back to the hearing and took her seat, even though she wasn’t a member of any of the subcommittees holding the hearing. She took the microphone and accused me of being dismissive of Chai Ling 柴玲 and other democracy activists.

I promptly forgot Senator Mathias’s advice and pushed back hard. I denied that my intention was to dismiss Chai Ling, spoke of my respect for her and other leaders of the protests, and went on to remind Mrs. Pelosi that the people of Hong Kong had marched in their millions in support of democracy in China. “All we are saying is, if you knock the underpinnings out from under our economy, we cannot continue to support reform and democratization.” After taking another shot at me, Mrs. Pelosi backed off.

Chairman Solarz took over. He asked a hypothetical question: if in fact removing China’s MFN would lead to better human rights in China, would I still oppose revoking the trade status for the sake of Hong Kong? “Are you saying Hong Kong uber alles?” he asked to laughter.

I had prepared for this very question. I brought up Abraham’s negotiating with the Lord to spare the wicked for the sake of the righteous.

The hearing ended at 3:22 p.m. Fortunately, Jeff Muir had left the hearing earlier and returned to the hotel, where he picked up our luggage and hired a cab to pick me up outside Rayburn. The driver knew the back roads to National Airport. I arrived in time for my flight. I needn’t have worried about Occidental’s reaction to my testimony: Chairman Armand Hammer fancied himself a friend of China, and I was told he loved my testimony.

“A Hero in Hong Kong”

I returned to Hong Kong where my work was applauded. Media coverage was heavy, with the front page of USA Today hailing me as “A Hero in Hong Kong.” I became known as Mr. MFN. Most importantly, I was told by Zhou Nan’s assistant that Yao Yongzhan would be released. I was elated but not convinced that this success was anything other than a fluke.

I cohosted Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji 朱镕基 on his visit to Hong Kong in June 1990. He let it be known that he had personally ordered the release of Yao Yongzhan. He had heard of what I had done at the Zhou Nan banquet and didn’t want to be upbraided by me in front of hundreds of people. It was a pleasant lunch. Zhu returned the favor by telling Newsweek that China didn’t care whether the country retained MFN or not. He claimed that only AmCham cared!

In early June 1990, President George H. W. Bush renewed China’s MFN for another year. In his extension statement, he mentioned testimony that Hong Kong would suffer if China’s trade status were revoked. It marked the first time in American history that Hong Kong had factored into an important foreign policy decision by the American government.