<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

This John Kamm Remembers is a continuation of last month’s installment, “Memories of 9/11,” which recounted August-September 2001, when Kamm was approached by Tina Rosenberg about being the subject of a New York Times Magazine profile, and Kamm’s experience in China in the wake of the September 11 attacks.

State Security

Tina and the photographer retained by the Times to cover our visit, Zeng Nian, arrived in Beijing from New York in the late afternoon of December 17, 2001. I met them in the lobby of the Jianguo. From the moment of their arrival going forward, we were the objects of attention by state security. One of my drivers later told me that he was summoned for questioning and shown photographs of our arrival at different ministries.

Tina and I had dinner at the Jianguo. We discussed the schedule for the days ahead.

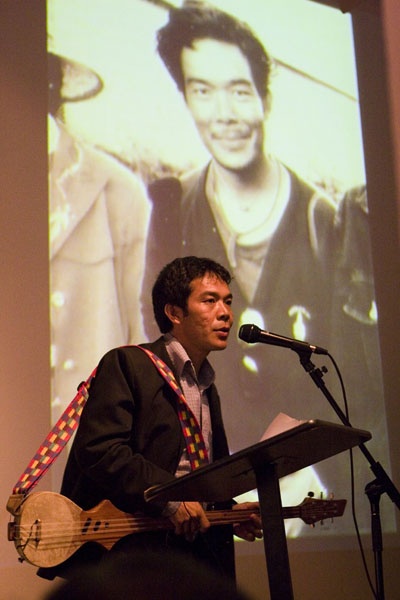

On December 18, Tina, Zeng Nian, and I went to the MFA for a meeting with Li Baodong. The purpose was to discuss the possible release of Ngawang Choepel, a Tibetan musicologist who had studied at Middlebury College in Vermont and had been detained in September 1995 on a trip back to Tibet to film folk dances and record traditional music, and to see his mother. His had become an important case for Senator Jim Jeffords, R-Vermont, a pro-trade politician who had nevertheless voted against China’s Most Favored Nation (MFN) in 2001 over the way Ngawang Choepel and his family were being treated.

While we were introducing ourselves in came Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing, who had recently returned to Beijing from Washington where he had served as ambassador. Li was familiar with the Ngawang Choephel case. Senator Jeffords’ vote against MFN had made an impression. After 9/11 Li Zhaoxing had recommended, to President Jiang Zemin, that political prisoners be released to improve the relationship with the United States, a seemingly contrarian move. Why make concessions to the United States when it was the United States that was seeking support from China?

At the MFA, Foreign Minister Li introduced Tina to Li Baodong. “This is the good Mr. Li,” he quipped. “There’s another Li who lives in Taiwan. He’s the bad Mr. Li.” The foreign minister was referring to President Lee Tenghui, seen by the Chinese government as enemy number one. After the foreign minister left the room, Li Baodong and I discussed the Ngawang Choepel case in cryptic terms. We agreed that we would meet again the next day.

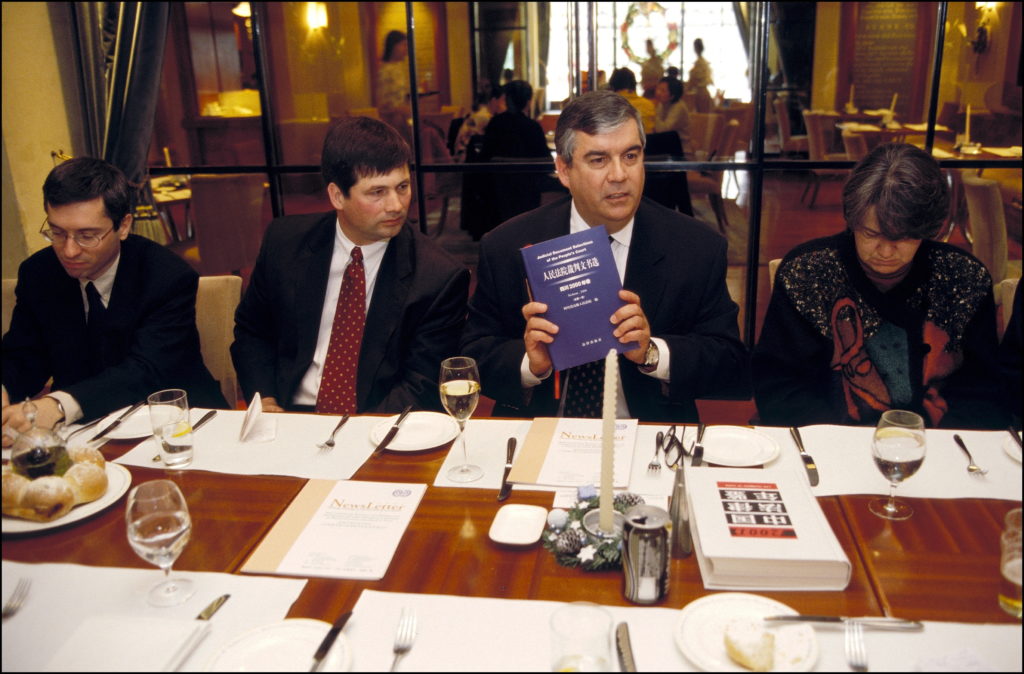

For lunch, Tina and I were hosted by a large group of foreign diplomats assembled by Mark Lambert, the US embassy’s human rights officer, in the best Italian restaurant in Beijing, Aria. They spoke one-by-one about their dealings with China on human rights. In those days, China was engaged in around 10 human rights dialogues with foreign countries. Now there are none.

Tina and I parted ways. I went on a visit to Beijing Number Two Prison. The MOJ had denied a request for Tina to join me. She went back to the MFA for a private interview with Li Baodong. We reconnected for dinner with Mark Lambert.

Not surprisingly. Tina wanted to gauge the opinion of American businesspeople about what I was up to, promoting respect for human rights on the part of the American business community in Beijing. I had set up a breakfast with the American Chamber of Commerce for 7:30 AM on December 19. Those at the table were defensive, citing the good work done for orphans and flood victims. Tina adopted a skeptical air. Outside the room, state security was listening.

After the breakfast, we went to the Supreme People’s Court for yet another uncomfortable meeting. The head of the Foreign Affairs Bureau, Mr. Liu Hehua, had clearly been caught off guard. I presented a letter from “my cousin,” Senator Orrin Hatch, and pummeled him with questions about the fate of the China Plum Blossom Party and the pamphleteer Yu Rong. I offered to provide assistance to Mr. Liu with materials on the American justice system.

As we were leaving, Mr. Liu took our photographer aside and sharply asked him about what was going on. The photographer was told that that he should be careful about who he worked for. It was not what the photographer, a French citizen with family in China, had anticipated.

There are two bookstores that were selling volumes related to judicial matters, including those related to trials for political offenses, near the Supreme Court. (NB: The bookstores no longer offer such books.) We surveyed their offerings under the watchful eyes of suspicious shopkeepers. I bought a couple, and then we were off for a photoshoot at the old Beijing railway station.

I departed Beijing on the 5:30 PM Dragon Air flight to Hong Kong. After three days doing research and briefing clients I returned to San Francisco on December 23, in time for Christmas.

On January 16, 2002, Tina called me with the news that her editor had decided that the entire article – now a profile – would be devoted to my work. The aim was to publish it on February 16. There followed more calls between Tina and me, one on February 5 devoted entirely to Ngawang Choephel’s release that had taken place on January 20. “Wrap up” interviews followed.

The first of two fact-checking interviews with the Times editorial staff followed. I was asked to estimate how many prisoners I had helped in the years since I began intervening on behalf of Chinese prisoners in May 1990. This entailed going over trip reports and notes. Finally, I estimated that I had helped around 250 political prisoners win early release or better treatment. During the last of these fact-checking interviews, I managed to tease the title of the article, now billed as a cover story for the Times’ Sunday Magazine, out of the fact-checker: “John Kamm’s Third Way.” I concluded that Chinese feathers would not be ruffled by this title. The story was slated to appear on Sunday March 3, 2002.

I left for Hong Kong on February 26, thence to Beijing on March 10. In Hong Kong, I intended having dinner with my Guangdong interlocutors, taping a show for VOA, giving a speech to the Asia Society, and conducting research in Hong Kong libraries. Most important, I wanted to gauge reactions to the cover story, due for publication during my days in Hong Kong.

On Friday, March 1, my cell phone went off while I was in the stacks of the Hong Kong University library. I stepped outside to take the call from my wife. The story had been published on the Times’ website on Thursday, February 28. “I thought you said that the title of the story was ‘John Kamm’s Third Way,”’ she said. “In fact, the title on the cover is ‘Kamm’s List.’” That’s when I learned that there are in fact two titles for a cover story. One for the cover, which is decided by the graphics people, the other inside the body of the article decided by the editorial staff.

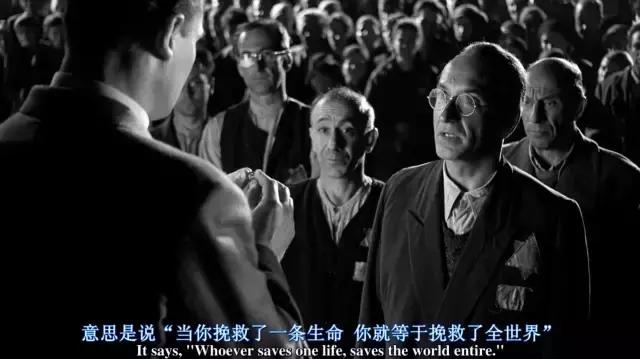

The latter was in fact “John Kamm’s Third Way.” The cover was a mockup of a movie poster that closely resembled one of the movie posters for Steven Spielberg’s 1993 hit movie Schindler’s List.

Schindler’s List

I shuddered. It would be hard to avoid the comparison between Kamm, saving Chinese prisoners from the Chinese government, and Schindler, saving Jews from the Nazis. I anticipated a sharp reaction from Chinese officials in Beijing – assuming I was allowed to enter the country.

I need not have worried. I entered China on March 10, 2002, without incident. The next day I met with Li Baodong and La Yifan. La advised me that he was monitoring reactions to the article among Chinese officials and National People’s Congress and political Consultative Congress deputies, assembled in Beijing for their annual meetings, the so-called “Two Sessions.” Thus far there had been no negative reactions. I told them that there was unhappiness with the article among American businessmen. Li Baodong airily waved his hand: “Don’t worry. They’ll get over it.”

A young official escorted me from the ministry to my car. “Imagine,” he said. “An article about human rights in China in which the Chinese government is not the biggest villain!”

On the afternoon of March 11, I went to the MOJ’s headquarters where I was received by two directors: Wang Lixian, head of the International Department, and Liu Fuchen, head of the Prison Administration Bureau. We sat down and director Liu fixed his eyes on me. “Mr. Kamm, wasn’t there an article about you published in the United States recently?” I said yes, there had been a story about me in the New York Times Sunday Magazine published a few days before.

“What was the title of the article,” Liu asked. “John Kamm’s Third Way,” I replied. Liu shot back. “No, that’s not the title I remember.” I explained that “Kamm’s List” was the title on the cover of the magazine. “John Kamm’s Third Way” was the title listed in the table of contents and inside the issue itself. Liu continued his line of questioning. “Wasn’t there a movie with a title similar to that?” I confessed that there was: “Schindler’s List.”

Liu rubbed his hands and exclaimed: “Won an Oscar, didn’t it? Excellent!”

An Unhappy Exchange

After a final meeting with Li Baodong on the morning of March 13, I went to the Supreme People’s Court where I was received by Liu Hehua. He was not happy, taking special umbrage at a line in the story: “Kamm not only speaks Mandarin and Cantonese but also the language of the party which is just as important.” Liu adopted a threatening tone. “This will not end well for you.” It turned out that Liu was relying on a translation of the article and not the actual article itself. I admonished him to read the original, and not rely on a translation.

I returned to Hong Kong on March 14 and flew back to San Francisco on March 17, satisfied that, while members business community were not happy – the head of a large business group that promotes trade with China was especially angry – the Chinese government was, for the most part, satisfied with the article, as was the case with the human rights community.

Today, “John Kamm’s Third Way” is required reading in courses on business and human rights, including those taught at Harvard Law School, Columbia Law School, and Princeton University. A testament to Tina Rosenberg’s writing, it has stood the test of time.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.