<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

Reflecting his background as president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong in 1990, the early trips businessman John Kamm made to Beijing to engage Chinese officials on human rights were hosted by the Chinese Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT). It was with the assistance of the CCPIT that Kamm first met with China’s Prison Administration Bureau (PAB), under the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), on October 17, 1991.

During that meeting, Kamm sat down with PAB Deputy Director Wang Mingdi and MOJ Foreign Affairs Department Deputy Director Zhang Yaochen to discuss the possibility of visiting one of the approximately 700 prisons under the control of the PAB in 1991.

The MOJ told Kamm that while it was not prepared to allow the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to visit Chinese prisons, it welcomed foreign visitors to its 31 “model prisons” and had hosted more than 20,000 of these visitors since 1979.

Opining that model prisons were unlikely to be representative of general prison conditions, Kamm asked the MOJ to consider allowing him to visit a prison that 1) had never been visited by a foreigner, 2) was not a model prison, 3) housed prisoners convicted of counterrevolutionary crimes (which are now mostly reclassified as endangering state security crimes), and 4) was located in a coastal region (coastal prisons were alleged to make goods for export).

Wang said the ministry would consider his request and asked if Kamm had any prisons in mind. Kamm named Huaiji Prison in western Guangdong Province, following a tip from Hong Kong businessman Luo Haixing, who was previously incarcerated there, that it had a specialized cellblock for people who had committed counterrevolutionary crimes. Wang said he would pass along the request, making clear that China would decide which prisons to open to outsiders.

The next day, on October 18, 1991, Kamm received a phone call inviting him to visit a prison that met all of his conditions: Meizhou Prison in northeastern Guangdong Province. He was told that no photography would be allowed during the visit.

Kamm immediately returned to Hong Kong to put together as much information as he could on Guangdong’s counterrevolutionary prisoners and Meizhou Prison. Using reports issued by international human rights organizations, Kamm put together a list of 13 people convicted of counterrevolutionary crimes who might be in Meizhou.

Armed with the list, Kamm took the train to Guangzhou on October 21 and flew to Meizhou on October 22. He was met at the airport by Guangdong’s Prison Administration Department Director Chen Weixiong and Meizhou Prison Warden Zhou Xiongxiang.

The men repaired to a small room at the airport where Chen and Zhou gave Kamm a “brief introduction” to Meizhou Prison, and Kamm gave them his list.

In late 1990, the Guangdong Prison Administration Department managed 20 prison and reform-through-labor brigades as well as several reeducation-through-labor camps. Only one facility was open to foreigners: the juvenile reformatory in Guangzhou. Generally speaking, prisons are used to house people with prison terms of 10 years or more, while detention centers run by public security bureaus house people awaiting trial as well as those sentenced to one or two years in prison who, because of the length of their sentences, are not transferred to prisons.

In 1990, the largest prison in Guangdong Province was Shaoguan Prison in the north, housing 3,000 prisoners. Huaiji held 2-3,000 prisoners, while Meizhou was considered average size at 1,500 prisoners and 300 staff who lived and worked at the prison with their families. Eighty percent of Meizhou prisoners had been convicted of a violent crime in Meixian, Shantou, and Heyuan municipalities; 30 percent had been convicted of murder; 20 percent of economic crimes, like embezzlement and corruption. Only about 10 prisoners had been convicted of counterrevolutionary crimes, typically of spying for Taiwan. Meizhou did not house any people convicted for offenses committed during the 1989 June Fourth protests.

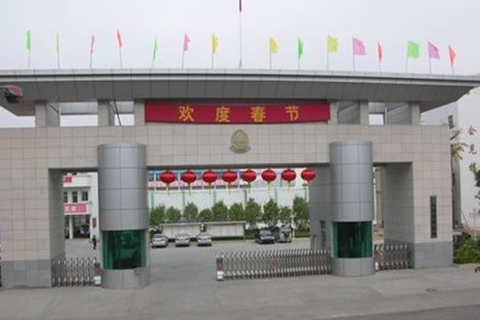

Kamm and his hosts left Meizhou Airport and headed directly to the prison in the center of Meixian Municipality. Founded in 1951, Meizhou Prison was built on the site of a former Guomindang detention facility.

They entered the prison complex from a bustling street through white gates with signboards that read “Meixian New Life Automotive Parts Factory.” Prisoners at Meizhou Prison manufactured wheel assemblies in three workshops. The officials insisted that none of the products, valued at RMB 5 million, were for export.

In the outer courtyard Kamm was shown the family meeting rooms where prisoners were allowed once or twice a month, the mail room, a shop selling products for visiting relatives to give to prisoners, staff quarters, and the prison administration offices. On the western side of the courtyard were a car repair workshop and a plastic bottle workshop with two injection molding machines. Family members of prison staff ran the workshops.

On the northern end of the outer courtyard was Meizhou Prison. Kamm passed through a large sliding gate and a separate entrance guarded by an armed sentry. The walls were 18-20 feet high and topped by electrified wires.

At the end of a 200-meter walkway flanked by vegetable fields, a pigsty, and lumberyards filled with laboring prisoners, Kamm entered the cellblocks. There were 11 cellblocks, each housing 120-130 prisoners, who stood at attention during his visits. In each block, there were cells of 28-32 bed spaces. The cells were spartan, but it appeared that electric fans had recently been installed. Each block had a television that prisoners were allowed to watch three times a week and a common latrine and shower area.

Kamm visited the prison kitchen, where he heard about the rations given to each prisoner. He then toured the clinic; a music room—where the prisoners played Jingle Bells on Chinese instruments for the duration of the visit; a library; and the prison school where classes were taught in politics, art, and mathematics. Pleasantries were exchanged with prisoners, who seemed amused by the first visiting foreigner to have set foot in the facility.

In the courtyard between two cellblocks, Kamm watched a 10-minute exercise session. He asked to see the solitary confinement area, but his request was denied. At the time of his visit, one prisoner was in solitary for trying to escape.

The warden said that torture was strictly prohibited, and guards who beat inmates were disciplined—in one instance, a guard was sentenced to prison.

Every day the wardens of each cellblock graded prisoners on a 10-point scale. Those who received a year’s worth of 10-point scores were virtually guaranteed a sentence reduction. In line with national averages, 30 percent of prisoners received sentence reductions every year. Parole, approved by courts, also took place, and prisoners were allowed to petition courts for their cases to be reheard.

In the workshops, Kamm observed rudimentary safety measures for tractor wheel assemblies. The environment resembled that of the scores of state-owned factories that he had visited in his business career: lots of idling, and low levels of efficiency.

After the visit to the workshops, Director Chen Weixiong of the Guangdong Prison Administration Department gave Kamm information on five of the 13 prisoners he had asked about.

Three individuals had spent time at Meizhou Prison: Mai Furen and Sun Ludian, pastors of the Shouters, an evangelical sect targeted in a nationwide campaign in late 1983, and Liu Shanqing (刘山青), a Hong Kong resident detained in December 1981 and sentenced to 10 years in prison for counterrevolutionary offenses. Mai, who was serving a 13-year sentence, was released to his family a few months before Kamm’s visit due to his advanced age. Sun, who was serving a nine-year sentence, was released on medical parole in December 1990. Liu had been transferred to Huaiji Prison in 1989 or 1990. Kamm asked that Liu be released and allowed to return to Hong Kong without serving his deprivation of political rights in China. He returned to Hong Kong on Christmas Day, 1991.

Director Chen also gave Kamm information on two people who had not been incarcerated in Meizhou Prison. Chen Zhixiang (陈志祥) and Chen Pokong (陈破空) were sentenced for counterrevolutionary offenses committed during the spring 1989 protests in Guangzhou. Chen Zhixiang, a teacher sentenced to 10 years in prison, was in a detention center awaiting prison placement. He eventually went to Shaoguan Prison from which he was released more than three years early in 1995. Protest organizer Chen Pokong received a three-year sentence that he served in a public security detention center. He served nearly his entire sentence and was subsequently sentenced to re-education through labor for illegal border crossing.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.