<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

Download & read this story as a PDF

In March 2006, the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) was established, replacing the much-criticized Human Rights Commission. One of the principal tasks of the HRC is to oversee the process known as Universal Periodic Review (UPR). Every four to five years, the human rights records of United Nations member states are examined with respect to their compliance with international human rights norms.

China’s first UPR was held in Geneva in 2009, followed by its second UPR in 2013 and its third UPR in 2018. China’s next UPR will take place in early 2024. The Dui Hua Foundation (Dui Hua), which is in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (ECOSOC), has attended all of China’s UPRs, and has made submissions at each one. It will make a submission to China’s January 2024 UPR in July 2023. It intends attending China’s fourth UPR.

One of the subjects examined at UPRs is whether the reporting state has issued invitations to special procedures (special rapporteurs and treaty bodies) to the reporting state. There are currently 59 special procedures.

After China’s first UPR, it invited the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Mr. Olivier de Schutter, to visit the country at the end of 2010, no doubt thinking that this would be a relatively benign and risk-free visit. Beijing is very sensitive to any criticism of its human rights record by international bodies, especially HRC and its special rapporteurs and treaty bodies.

Upon his return to Geneva from his mid-December 2010 visit, Mr. de Schutter made a report. While noting the advances made by China, the report also referenced “specific challenges” that needed to be addressed, including agricultural sustainability and food insecurity in poor and rural areas, food safety, and land degradation and pollution. An entire section was devoted to criticizing China’s policies targeting nomadic herders in Tibet and other minority areas. Beijing was not happy, and no more invitations to special procedures were issued in 2011 and 2012.

As China approached its third UPR to take place in October 2013, its Ministry of Foreign Affairs considered whether or not to invite a special procedure to visit the country. I was asked for my advice. I was inclined to recommend the Working Group on the Issue of Discrimination Against Women in Law and Practice (WGIDAWLP) but first I needed to ascertain whether the working group was interested in making a formal visit.

I asked friends in Geneva and was told that the group had only been established in 2010 and as such it was the “new kid on the block.” Many other special procedures were waiting for invitations. I decided to ask the working group anyway and was pleasantly surprised to learn that it was interested to visit China. I made a suggestion to the MFA that the group be invited.

I arrived in Geneva from Oslo on Sunday October 20, 2013, and checked into my usual haunt, the Hotel Ambassador. I had dinner at a nearby Chinese restaurant and settled in for the night. In addition to attending China’s UPR, where I was informed that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had accepted my suggestion to invite the working group, I met with American and Chinese diplomats, UN officials, the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Assembly, and the president of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Peter Maurer.

At my meeting with the WGIDAWLP on October 24, I was thanked for my work lobbying the Chinese government to issue the invitation – the visit took place two months later in December 2013 – and discussed their and UNOHCHR’s possible attendance at Dui Hua’s international symposium on Women in Prison (the Bangkok Rules), set to take place in Hong Kong in February 2014.

Women in Prison

The symposium took place as planned. Dui Hua partnered with the University of Hong Kong and China’s Renmin University. A member of the WGIDAWLP, Elenora Zielinska, attended and presented a paper on the group’s 2010 visit to China. The OHCHR sent a representative, Adwoa Kufuor, to make a presentation on the treatment of women prisoners under international human rights law.

China sent the largest delegation to the symposium; it included scholars from the Supreme People’s Court and several research institutes and law schools who presented papers on domestic violence, women law enforcement officers, and treatment of female juvenile offenders in Beijing, and, separately, treatment of female prisoners in Hong Kong. (Hong Kong has one of the highest percentages of women prisoners of any country or territory in the world). Findings of a survey of five places of detention for women in China, commissioned by Dui Hua and conducted by scholars at Renmin University led by Professor Cheng Lei, were presented.

The symposium’s delegates visited Hong Kong’s largest women’s prison and held discussions with the territory’s authorities in charge of women prisoners. Most important, the symposium, attended by one of the judges tasked with reviewing death penalty decisions, contributed to the overturning of a death sentence for a victim of domestic abuse who murdered her husband.

On a follow-up visit to Beijing, I was advised by a senior official of China’s National People’s Congress that the legislative body would consider where the Bangkok Rules could be incorporated into Chinese legislation.

Girls in Conflict with the Law

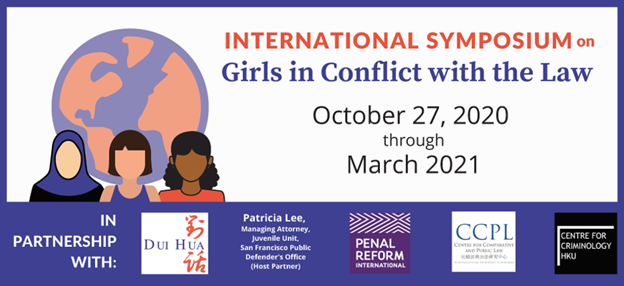

The International Symposium on Women in Prison set the table for the International Symposium on Girls in Conflict with the Law. Unlike the women in prison symposium, which was held in person, the girls in conflict with the law (GCIL) symposium was held virtually due to the Covid-19 pandemic. From October 2020 to March 2021, 12 webinars featured experts from 18 countries discussed topics related to the treatment of girls in the justice systems of countries on five continents.

The final topic was a presentation by China’s Supreme People’s Court – “Special and Priority Protection of the Legitimate Rights and Interests of Underage Girls in Accordance with the Law,” featuring Dui Hua’s long-time partner Judge Jiang Jihai and his colleagues.

There is no contradiction between Dui Hua’s work on women prisoners and girls in conflict with the law, on the one hand, and our work on political and religious prisoners on the other. From the earliest days of my advocacy to the present, I have worked on numerous cases of women and girls who have been detained and imprisoned, including Ngawang Sangdrol and the Drapchi nuns, Liang Shaolin and dozens of other women subjected to coercive measures for practicing unorthodox religions, American citizen Sandy Phan-Gillis, and Rebiya Kadeer and other Uyghur women. To Dui Hua, Mao Zedong’s claim that “Women hold up half the sky” is more than a slogan. It is a core belief at the center of our work.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.