<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

Harvard Professor Ezra Vogel, a widely acknowledged expert and prolific writer on Japan and China, passed away in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on December 20, 2020. He was 90 years old.

I got to know Professor Vogel in the 1980s when, on several extended visits, he resided in Guangzhou conducting research for what was to become One Step Ahead in China: Guangdong Under Reform (Harvard University Press, 1989). He was joined by his wife Charlotte Ikels, an accomplished anthropologist studying Chinese society.

After attending the trade fairs in 1976-1979, I opened the first foreign office in Guangzhou in 1979 and worked out of a suite of rooms in the Dongfang Hotel. I later moved the office to the Garden Hotel. By 1988 I had visited nearly every prefecture in the province, meeting with factories and running agricultural chemical field trials. In this I was aided by my knowledge of Cantonese.

As a long-time resident of the Dongfang, I managed to get my hands on a Hitachi air conditioner. China had purchased several hundred of these machines after the Tangshan earthquake in which a number of Hitachi engineers had perished. The air conditioners spent several months stacked in the heat and humidity of the Dongfang’s courtyard.

Unfortunately, the hotel’s power system could not handle the increased load of multiple air conditioners blasting away, so only a few of the Hitachi air conditioners were ever installed.

It didn’t take long for Ezra to hear about my air-conditioned suite, and he became a frequent visitor. He was staying at Zhongshan University south of the river. In the sweltering heat of the summer months, we would drink beer in the office and sometimes go out for walks to local restaurants and parks. We spent many hours in long conversations about how Guangdong had changed since I first visited the city in January 1976, just as the Cultural Revolution was beginning to wind down.

Guangzhou underwent great changes in the aftermath of the reforms initiated in late 1978, changes that Ezra chronicled in One Step Ahead in China. I had been involved in early joint venture discussions and made some of the first sales to county foreign trade organizations. I willingly became a resource for Ezra. Eventually he asked me to write a chapter for the book, which I gladly did.

While Guangdong was undergoing great economic changes, many of which I chronicled in my magazine Canton Companion, that was not the case with political change. Like all other Chinese provinces, Guangdong was under the firm control of the Chinese Communist Party.

A couple of examples serve to illustrate the dichotomy between economic reform and the lack of political reform.

In May 1982, democracy activist Wang Xizhe was sentenced to 14 years in prison for counterrevolutionary activities. Wang was a member of the Li Yizhe group that composed and put up a long essay on democratic and legal reform in 1974. The group was eventually imprisoned, but they were exonerated and released not long after the Gang of Four was overthrown in October 1976. While other members of Li Yizhe adopted relatively low-key lifestyles, Wang remained politically active. (He was released early in 1993 after my spirited intervention with China’s State Council.)

While Wang’s trial was taking place, the China Hotel, China’s first foreign joint venture hotel, was being built adjacent to the Dongfang Hotel. This was the brainchild of Hong Kong businessman Gordon (now Sir Gordon) Wu. He was and remains a firm believer that economic change will eventually lead to political change. In addition to the China Hotel, he built the Shenzhen Guangzhou highway as well as the Shijiao power station in Guangdong. The latter venture significantly increased power supply in the Pearl River Delta.

On our walks around the city, Ezra and I often came across announcements of executions. These announcements were written in black ink on large posters with a distinctive red check – indicating that the execution had taken place – on the bottom of the announcement. I referenced the wave of executions that followed the first Strike Hard Campaign in 1983-84 in my chapter, estimating that Guangdong accounted for 1,000 of the 10,000 executions in China in the autumn of 1983. I also devoted space to chronicling worker unrest in the special economic zones.

By 1988 the manuscript – “With a contribution by John Kamm” – for One Step Ahead was ready for footnoting and editing. Unexpectedly, political unrest broke out in Beijing and other Chinese cities including Guangzhou. Many people were killed or wounded, and thousands were detained. To people like Ezra Vogel and me these events were shocking. My views of China changed, and I began to work on human rights.

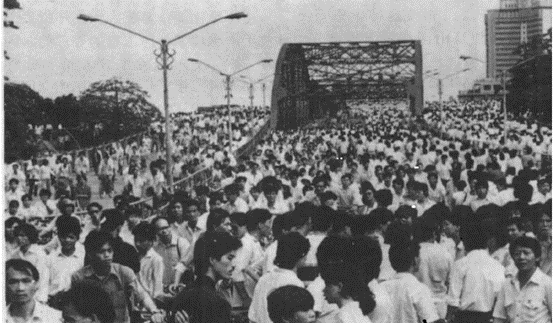

Ezra was especially upset by the arrest of young students and teachers. Chen Pokong was a teacher at Zhongshan University while Ezra was in residence. He was also the honorary president and advisor to the Guangzhou Students Autonomous Federation, a group that distinguished itself by organizing blockades of bridges over the Pearl River during May and June 1989. He founded a political party and issued a manifesto calling for human rights and rule of law. Chen Pokong was sentenced to three years in prison for counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement. Released after serving his full term, Chen returned to activism and was sentenced to a two-year term of re-education through labor in 1993.

I took a special interest in the case of Yi Danxuan, a student leader who, like Chen Pokong, organized the blockade of the Pearl River Bridges, He was sentenced to three years for counterrevolutionary activities. Identified as a businessman, I announced his release one year early on August 13, 1991.

A student activist who received the longest sentence – 10 years – for June 4-related activities was Chen Zhixiang, a teacher detained for writing anti-government slogans throughout the city. He was released four years early in November 1995.

As the publication date of One Step Ahead neared, Ezra wondered whether to address the killings and arrests of the 1989 protest movement. I encouraged him to do so. Finally, he penned a preface to the book that was released in December 1989. The opening sentences reveal the strength of Ezra’s condemnation:

“In June 1989 the massacre of students in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square stunned China and the rest of the world. It was not the first time that China’s rulers had ordered soldiers to slaughter unarmed civilians. . .The 1989 massacre was the first such atrocity played out under the vigilant eye of modern telecommunications, and it was thereby instantly and dramatically accessible to people everywhere. It marked the definitive end to an era in which the Chinese state could monopolize the flow of information in and out of China.”

One Step Ahead was to play a role in another case that brought Ezra and me together. In the summer of 2000, Xu Zerong, a Hong Kong resident and Guangzhou professor, was arrested for trafficking in state secrets. Xu, aka David Tsui, had translated an early draft of One Step Ahead and had stayed in close contact with Professor Vogel. The Harvard professor asked me to intervene on Xu’s behalf and I did so, liberally using Vogel’s name in my pleas to Guangdong officials. Vogel was well-liked and influential in Guangdong Province. His interest in Xu Zerong’s fate played a role in the decision to release him two years early, in June 2011.

In his many years in academia and government service, Ezra Vogel was seen as a mild-mannered, cautious man little interested in the struggles of the Chinese people for human rights and rule of law. That was not the Ezra Vogel I got to know. He worked behind the scenes on important causes like helping scholars disliked by Beijing secure visas. He was a long-time supporter of Dui Hua, and the source of much sage advice. He helped organize some of my speeches at Harvard. Ezra tried to bring the countries together, an increasingly difficult task in recent years. He will be deeply missed.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.