EVENTS

Barnstorming in Cambridge

Dui Hua Executive Director John Kamm and Dui Hua Senior Manager for Research and Database Kevin Li spent the week of October 20, 2019 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Kamm delivered remarks on four occasions at Harvard University and Boston University. When not speaking, Kamm joined Li in carrying out research in three Harvard libraries. They found information on more than 200 individuals subjected to coercive measures, including hitherto unknown details of the New Era Communist Party of China, a group whose leader was sentenced to life in prison for subversion, the longest sentence for this crime registered in Dui Hua’s political prisoner database.

Kamm and Li spent many hours probing Harvard’s latest acquisition, a 12-volume set of books, compiled and published by China’s Supreme People’s Court, that provide statistics on all civil and criminal trials in China from 1950 to 2016. Among the important findings were details on girls tried by Chinese courts in recent years. Dui Hua is working with partners to hold the first international symposium on girls in conflict with the law in Hong Kong in April 2020.

Overall, Kamm’s university remarks were attended by more than two hundred people, including leading Sinologists based at the two universities: William P. Alford, Vice Dean for the Graduate Program and International Legal Studies at Harvard Law School; Dwight Perkins, Harold Hitchings Burbank Research Professor of Political Economy at Harvard University; Ezra Vogel, Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences Emeritus at Harvard University; and Joseph Fewsmith, Professor of International Relations and Political Science at Boston University. Kamm and Li met separately with Mark Elliott, Vice Provost of International Affairs and Mark Schwartz Professor of Chinese and Inner Asian History at Harvard University.

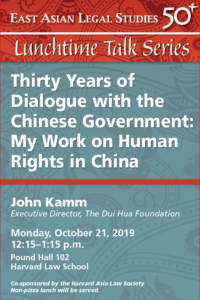

Kamm’s first remarks were delivered at Harvard Law School on October 21, 2019. Titled “Thirty Years of Dialogue with the Chinese Government: My Work on Human Rights in China,” the speech covered Kamm’s history of human rights activism since his first intervention on behalf of a political prisoner in May 1990. The next day, October 22, Kamm spoke on the same topic at Boston University.

On October 24, 2019, Kamm addressed a large audience on the topic “Counterrevolution in One Country: China, 1989.” Drawing on statistics for the crime of counterrevolution from 1989 to 1991, the years during which trials took place for counterrevolutionary offences committed during the Tiananmen protests of 1989, Kamm’s presentation drew a new picture of individuals who were convicted and sentenced for the most serious crime in China’s criminal law during those years. Findings from Dui Hua’s research reveal that the largest group of these counterrevolutionaries were farmers. Nearly all counterrevolutionaries sentenced were males and most were over the age of 25. Three quarters of counterrevolutionaries were tried for non-violent offenses, and they benefited from unusually high rates of acquittal. Comparing what he found in the material from the Supreme People’s Court with data in Dui Hua’s political prisoner database, Kamm concluded that no more than 15 percent of the names of those tried for counterrevolution in 1989-1991 are known outside China.

Kamm capped off his visit by participating in a panel held on the evening of October 24, 2019 of alumni who graduated from the Regional Studies–East Asia [RSEA] program at Harvard University. In attendance were students currently enrolled in the program. Kamm discussed career opportunities at the intersection of human rights and business.

Following the week in Cambridge, Kamm traveled to Washington, D.C., where he was joined by Dui Hua Senior Manager for Publications and Programs Elizabeth Cole. They met with American officials working on China in the Office of American Citizen Services, the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, and the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, including recently confirmed assistant secretary Robert Destro. Kamm met separately with the China team at the National Security Council as well as senior staff of the Congressional Executive Commission on China and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

PRISONER UPDATES

As reported in our lead story, above, in late October, Kamm and Li spent a week at three Harvard libraries delving into public security, procuratorate, court, prison, and administrative gazettes, many of which are inaccessible to the public elsewhere in the world. Their research uncovered information about the “People’s Party” founded by Dong Zhanyi (董占义). The government record also revealed that Chen Guohua (陈国华), another founding member of Dong’s party, was sentenced to 14 years’ imprisonment for subversion on October 27, 2011. As Dui Hua previously reported, this organization, later renamed the “New Era Communist Party of China,” aimed to fight corruption and recruit aggrieved workers and petitioners to overthrow the Community Party of China.

Dui Hua’s research uncovered four previously unknown names who were implicated in Dong’s party: Liu Jinlong (刘金龙), Zhang Xinxiang (张新祥), Yu Yingbin (余应斌) and Zhan Wenfang (湛文芳): all of them were sentenced in Beijing for subversion, while two were additionally sentenced for fraud. A government record stated that they were employees of Tongkang (通康), a corporate entity that allegedly promoted an investment scam in the name of a supermarket project. The party members lived in a number of locations across China, including Beijing, Tianjin, Henan, Shandong, Anhui, Jiangsu, and even Ningxia. In Beijing alone, Tongkang was accused of fraudulently raising 2.9 million yuan from investors. Dong and other members were said to have used Tongkang to fund their political activities, which included assassination plots and procurement of knives and crossbows.

The government record also revealed that Chen Guohua (陈国华), another founding member of Dong’s party, was sentenced to 14 years’ imprisonment for subversion and fraud on October 27, 2011. Chen was responsible for writing propaganda about ending one-party rule and establishing a multi-party system. On the same day, the Beijing No. One Intermediate Court sentenced Liu and Zhang to 17 years’ imprisonment for the same charges. Yu and Zhan were sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment for the sole charge of subversion. As of November 2019, Dui Hua’s PPDB has information on 14 individuals who were detained or sentenced in connection with Dong’s party.

PUBLICATIONS ROUND UP

Featured: Human Rights Journal, November 7, 2019: China’s Supreme People’s Court Releases Detailed Statistics on Trials, 1949-2016

Criminal Trials

China’s Supreme People’s Court (SPC) has compiled and released detailed statistics covering the adjudication work of China’s courts from 1949 to 2016, inclusive. The first six volumes are devoted to criminal trials of the first and second instance as well as retrials. They include breakdowns of cases and individuals in trials accepted, concluded, and held over for each article of the Criminal Law, as well as information on sentences, supplemental sentences (e.g. deprivation of political rights), age, occupation, gender, and, in recent years, ethnicity of defendants.

Records of People’s Courts Historical Judicial Statistics: 1949-2016 (Renmin fayuan sifa tongji lishi dianji 人民法院司法统计历史典籍) was compiled and edited by the SPC. It was published in September 2018 by the China Democracy and Legal System Press under the National People’s Congress. It became available in March 2019, but thus far the 12-volume set, priced at RMB 1,980, has attracted few readers and received little attention from scholars. Information is not provided on the number of volumes published.

The sets are marked “for internal release” (neibu faxing 内部发行). A small market in second-hand volumes has emerged. Dui Hua has purchased a set. All 12 volumes are available at the H.C. Fung Library of the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University.

The publication of these volumes is a major step forward for judicial transparency in China and is a boon to scholars studying China’s justice system.

In the coming months, Dui Hua will release reports in its Reference Materials series and Human Rights Journal that will draw on topics derived from the statistics published in the 12-volume set. Topics will include use of Article 300 to suppress unorthodox religious groups; trials of Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan residents as well as foreigners; splittism and inciting splittism; espionage and trafficking in state secrets; Cultural Revolution court trials; and treatment of juveniles, including girls, in the criminal justice system.

Continue this story here.

JOHN KAMM REMEMBERS

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s human rights advocacy prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999.

Dui Hua’s First Trip to Beijing, May 2000

The Dui Hua Foundation was established in April 1999. That same month, the United States introduced a resolution criticizing China’s human rights record at the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. The Ministry of Justice (MOJ) advised me that they would no longer provide information on prisoners “for reasons known to all.”

On May 7, 1999, American warplanes bombed the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade, touching off a major crisis in U.S.-China relations. China immediately suspended the official human rights dialogue with the United States. Since Dui Hua’s unofficial dialogue had already been suspended, the suspension of the official dialogue did not affect us. In fact, it enabled our dialogue to be resumed before the government-to-government dialogue.

My wife and I made a personal donation through the Chinese Embassy in Washington to the families of the Chinese killed in the Belgrade Bombing. I was advised by a senior Chinese official that we were the first American citizens to make this gesture, which was much appreciated.

On March 21, 2000, I received a letter faxed from the MOJ. The letter thanked me for “all your hard work over these past several years to promote understanding between our two sides.” Attached to the letter was information on 14 prisoners about whom I had asked. The letter marked the resumption of Dui Hua’s dialogue on prisoners with the Ministry of Justice, something I called “the Prisoner Information Project.”

The first prisoner about whom information was provided was Bai Weiji (白伟基), an official of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs who had led a march during the Spring 1989 protests, for which he was fired and expelled from the Communist Party. Bai was detained on May 5, 1992 and subsequently tried and convicted for “illegally providing state secrets to a foreign organization.” His wife, Zhao Lei (赵蕾) , was arrested a year later, and sentenced to six years in prison. (She was released early after an 18-month sentence reduction.)

Bai was given a 10-year prison sentence. He had provided documents to the Beijing Bureau chief of The Washington Post, Ms. Lena Sun, for whom his wife worked. The documents were found during a police raid on Ms. Sun’s apartment. In her safe were 10 “top secret” documents, according to Xinhua News Agency. Ms. Sun asked me to help secure Bai Weiji’s release, and I began raising his name with Chinese officials and submitting lists with his name on them to the MOJ.

The March 21 letter advised that Bai had received three sentence reductions and been released more than three years early on February 2, 1999.

Not long after receiving the letter, the MOJ invited me to visit Beijing. It would be the first visit by Dui Hua to Beijing and the first visit by a foreign human rights organization to discuss China’s prisoners with the ministry in charge of the country’s 700 prisons.

Prior to leaving for Beijing, I received a letter from Mr. Samuel (“Sandy”) Berger, President Bill Clinton’s National Security Advisor. The letter asked me to follow up on President Clinton’s request, made during his trip to Beijing in June 1998, to release the remaining counterrevolutionaries serving sentences in China’s prisons. The fate of these prisoners would be the focus of my trip to Beijing.

I arrived in Beijing on May 18, 2000. Before I departed on May 20, I met with MOJ Vice Minister Fan Fengping and held 10 hours of talks with officials of the Prison Administration Bureau and the Department of Judicial Assistance as well as Director Liu Huaqiu, head of the Foreign Affairs Office of the Communist Party’s Central Committee, and senior officials of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Meetings were held in the ministry’s nearly opened headquarters in Chaoyang District.

I was given a great deal of information on counterrevolutionary prisoners. At the end of 1999, there were 1,300 such prisoners still serving sentences, a reduction of 650 from the end of 1997. Most of those released were released early, including several I had advocated for: Bai Weiji, Shandong’s Zhang Xiaoxu (张霄旭) (paroled in 1998 after serving less than nine years of a 15-year sentence), and Tibet’s Jampa Ngodrup (released three years early in 1999). Immediately prior to my visit, Chen Lantao (陈兰涛), a student leader in Qingdao, was released after serving less than 11 years of his 18-year sentence for counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement and blocking traffic. Chen’s sentence was the longest for non-violent actions taken during the Spring 1989 protests, and I had taken a special interest in his case, raising his name on trips to Qingdao.

I raised the case of Zhang Jie (张杰), another Shandong prisoner whose case had been taken up by Congresswoman Lynn Woolsey and 15 other members of Congress. I was told that Zhang had had his sentence reduced by four and one-half years. The sentence was due to expire on January 15, 2003. I pressed hard for his release before then, and was told that if Zhang continued to “make progress in his reform” he would be released early.

I handed over a new list of 25 cases involving 51 individuals. Dui Hua had found their names in its research into “open source” Chinese publications. Most of their names were not known outside of China.

A highlight of the trip was a visit to Beijing Number One Prison in Daxing County on May 19. This was the prison where Bai Weiji had served his sentence, and I was eager to take a look at conditions there.

I left my hotel at 1:00 PM, and arrived at the prison an hour later. I was greeted by Warden Yang Di, a big man with a broad smile. He had earned a reputation as a warden who, though strict, cared about the prisoners under his charge.

Yang gave me the standard “brief introduction” and showed me around the prison’s spacious and well-tended grounds. I was shown a cell block, the infirmary, and the cafeteria. The prison occupied an area of 440,000 square meters. Established in 1982, it held 2,000 male prisoners overseen by 370 guards.

The prison was a hive of small factories, and included 18 workshops making automobile parts (some for export, although not to the United States), plastic packaging, steel templates, and toys, among other products.

Beijing Number One Prison, now known as Beijing Municipal Prison, was designated a model prison by the Ministry of Justice and one of only seven “Cultural Units” (wenming danwei 文明单位) by Beijing Municipality. To be designated a model prison, a carceral facility has to meet 42 conditions including “no prison escapes” and “no prisoner suicides.” Beijing Number One enjoyed a recidivism rate of less than two percent.

Prisoners ranged in age from 18 to 60. Sentences included life in prison, 16-20 year terms, 10-15 year terms, and under 10 year terms. Most sentences were 15 years or more. Fifty percent of prisoners would be granted sentence reductions or parole during their time at Beijing Number One. Medical parole was granted to prisoners near death who did not represent a threat to the community. Fifty-two percent of prisoners had committed property crimes and 30 percent had committed violent crimes, including sex crimes. Several officials were serving sentences for corruption.

As I boarded my car to return to my hotel after a four-hour visit, I asked Warden Yang if he remembered Bai Weiji. He remembered Bai as a well-behaved prisoner who had been released early.

Years after I visited Beijing Number Two Prison, Bai Weiji came to visit me in the United States. He told me about his life in prison. He had acted as a translator for Warden Yang’s efforts to sell prison-made automobile parts abroad. The warden had treated him well.

Bai thanked me for intervening on his and his wife’s behalf. While he credited my efforts for helping him gain early release, he cited two other reasons.

First, his team had won a city-wide competition among prisons to see who knew the most about Hong Kong’s reversion to China in 1997. Although he gained points for use towards a sentence reduction, his team members were given twice as many points as Bai because Bai was a counterrevolutionary.

The other reason had to do with the visit by the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) in July 1996. This visit, made by the Chairman-Rapporteur Louis Joinet, was to make arrangements for a trip to China by the full working group in 1997. Two carceral facilities were selected for visits by Joinet: Beijing Number One Prison and a reeducation-through-labor camp in Shandong Province.

Part of the agreement between China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and the WGAD was that randomly-selected prisoners could be interviewed in private, with no prison officials present. Upon arrival at Beijing Number One Prison, Joinet randomly selected Bai Weiji. Bai was the only political prisoner housed at the prison, and his selection was greeted with alarm and suspicion by the prison officials. They refused to let Joinet interview Bai. This led to a stand-off that was only resolved when a senior MFA official arrived to negotiate a solution.

Eventually, Joinet was allowed to interview Bai in a small room off the prison courtyard. Although the interview was supposed to be private and out of earshot, Bai suspected that the conversation was being monitored. Accordingly, he was very guarded. He declined to say why he was in prison, and claimed that he was being well treated. For this performance, Bai was given three successive sentence reductions, totaling three years and three months, in 1996, 1997, and 1998.

Not long after Bai visited me, I flew to Geneva. I requested, and was granted, a meeting with the WGAD. When I told them that the prisoner that Mr. Joinet had selected was the only political prisoner in the prison, they were shocked. I let them know that, because of the way he had handled the interview, Bai was released early, and was now a successful businessman able to travel abroad.