EVENTS

Despite Headwinds, Important Achievements in 2018

Last year, 2018, was a challenging time for NGOs working to promote human rights and rule of law in China. In Xinjiang, government and media reports alleged that one million Muslims were interned in reeducation camps – called “vocational training centers” by the Chinese government. A nationwide crackdown against Christianity, marked by the razing of churches, the tearing down of crosses and the detention of leading Christian leaders like Pastor Wang Yi, was reported to be underway. The use of “exit bans” to stop foreigners from leaving China prompted a State Department travel advisory. In an apparent response to the detention of a prominent Chinese businesswoman by the Canadian authorities, two Canadian citizens were detained in China on suspicion of espionage in December.

The backsliding on civil and political rights took place against the backdrop of a slowing Chinese economy and heightened tensions with the United States over several issues, notably trade and national security. Senior American officials ramped up criticism of China over human rights. Despite quitting the United Nations Human Rights Council in June, the United States participated in China’s third Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of its human rights record in November.

At its UPR, China revealed that 427 foreign NGOs had registered in China by the time of the review. This marks a sharp drop in the number of NGOs operating legally in the country. Thousands of NGOs were operating before the Foreign NGO Management Law took effect on January 1, 2017.

Despite these challenges, Dui Hua recorded significant achievements in its dealings with the Chinese government.

Advocacy on Behalf of Political Prisoners

In 2018, Dui Hua met with Chinese officials to discuss human rights, including individuals detained for endangering state security (ESS) and cult activities, on 25 occasions. Meetings took place in Beijing, Hong Kong, San Francisco, New York, and Geneva. At these meetings, lists of names of political and religious prisoners were handed over. In all, Dui Hua submitted 52 lists with 199 names during the year.

In all, 74 written responses to names on Dui Hua lists were received in 2018. This compares to 66 written responses received in 2017. Dui Hua learned of 56 acts of clemency or better treatment for prisoners on its lists, an uptick over what the foundation learned in 2017 when it was informed of 32 acts of clemency or better treatment.

Dui Hua remains the only governmental or non-governmental body, apart from United Nations Special Procedures, able to submit lists to the Chinese government and receive written responses in return.

Dui Hua’s Political Prisoner Database (PPDB) ended 2018 with nearly 40,000 records, an increase of 2,000 records over the number at the end of 2017. In 2018, 187 individuals sentenced for ESS crimes were added to the database, compared to 111 in 2017. Dui Hua’s work uncovering political cases on court websites continues to bear fruit: 95 new ESS cases were found on judgment websites compared to 64 in 2017.

Girls in Conflict with the Law

Preparations to hold the first international symposium on girls in conflict with the law made significant progress in 2018. The symposium, the first of its kind, will be held in Hong Kong in April 2020. Hong Kong University School of Law’s Centre for Comparative and Public Law, Patricia Lee (Managing Attorney of the San Francisco Public Defender’s Juvenile Unit), and London-based Penal Reform International are partnering with Dui Hua. Expert presenters and observers from Europe, Asia, and North America have been identified and invited, and possible funders were approached, with good results.

The symposium is receiving interest and support from China. The Supreme People’s Court Office of Juvenile Courts has been invited. Renmin University School of Law agreed to conduct a study on girls in detention in China. The results of the study will be presented at the symposium.

Girls in conflict with the law are a growing population of at-risk detainees, yet their needs are not adequately addressed. Girls are at greater risk of sexual abuse than boys, are more likely to be victims of sexual trafficking, are more prone to alcohol and drug abuse, and are more prone to suicidal thinking and violence.

Death Penalty

The year ended with 3,221 records of executions in Dui Hua’s Death Penalty Log. The log contains records of 1,087 death sentences reviewed by the Supreme People’s Court. From 2014-2018, Dui Hua found 61 death sentences overturned, giving a reversal rate of 7.7 percent.

Dui Hua’s estimates of the number of executions are held in high regard. The foundation estimated that there were 2,000 executions in 2018, a small decrease from the number of executions in 2017.

PRISONER UPDATES

In December, Dui Hua received information from our interlocutors on seven prisoners in Shanghai. The response confirmed the whereabouts of two Falun Gong practitioners convicted of “organizing/using a cult to undermine implementation of the law”. Wu Xiaocun (吴啸村), who is currently serving in Tilanqiao Prison, will complete his four-year sentence on May 12, 2021. Female Falun Gong practitioner Zhong Yijun (钟怡君) is due for release from Nanhui Prison on January 2, 2021.

The same response also indicated that Jiang Cunde (蒋存德) remains incarcerated for counterrevolution, a crime that was removed from the Criminal Law over 20 years ago. Jiang has not received any form of clemency since his life sentence was commuted to 20 years’ imprisonment in 2004.

Two activists were convicted of inciting subversion in December. A Guangdong court sentenced Zhen Jianghua (甄江华) to two years’ imprisonment in December. Zhen administered a website which shared news about human rights activists across the country and ran another website that helped internet users to circumvent censorship. Jiangsu activist Sun Lin (孙林) was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment and three years’ deprivation of political rights. Lin was accused of circulating online articles that discussed political issues and democracy as well as for chanting ‘Down with the Communist Party’ at a community meeting with communist party members in Nanjing.

DUI HUA IN THE NEWS

Dui Hua was cited in New York Times articles on forced labor in Xinjiang and the retrial and death sentence of a Canadian citizen in China. In the article on forced labor in reeducation camps in Xinjiang, Executive Director Kamm was quoted saying “I don’t see China yielding an inch on Xinjiang. Now it seems we have entrepreneurs coming in and taking advantage of the situation.” In December, Robert Schellenberg, a Canadian national who was arrested in 2014 and tried and sentenced in obscurity in China became the focus of international attention after news that his retrial in January could result in a death sentence. After Canadian authorities arrested Meng Wanzhou, the chief financial officer of the Chinese technology company Huawei, diplomatic tensions between Canada and China have worsened. On January 14, Schellenberg’s retrial resulted in a death sentence. Dui Hua’s research on the number of foreigners executed in China for drug charges was cited by the media and Kamm was interviewed by Canadian media outlets about the Schellenberg case.

PUBLICATIONS ROUND UP

Featured: Administrative Penalties Against Lawyers: Another Strike Against Professional Autonomy and Religious Freedom

The recent license suspensions of two lawyers in Yunnan have come under public scrutiny for the strange circumstances that led to the suspensions: the lawyers were making legal arguments based on government regulations and criminal statutes, with citation to relevant parts of the national constitution, on behalf of their clients. Their plaintiffs were Falun Gong practitioners accused of “using a cult to undermine the implementation of the law.” The case sheds light on a pattern emerging in the legal profession in China – the penalization of criminal defense attorneys, who represent clients in sensitive cases, with legally dubious accusations of professional misconduct.

John Kamm Remembers

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s human rights advocacy prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999.

Li Yan Has Survived! (Part 2 of 2)

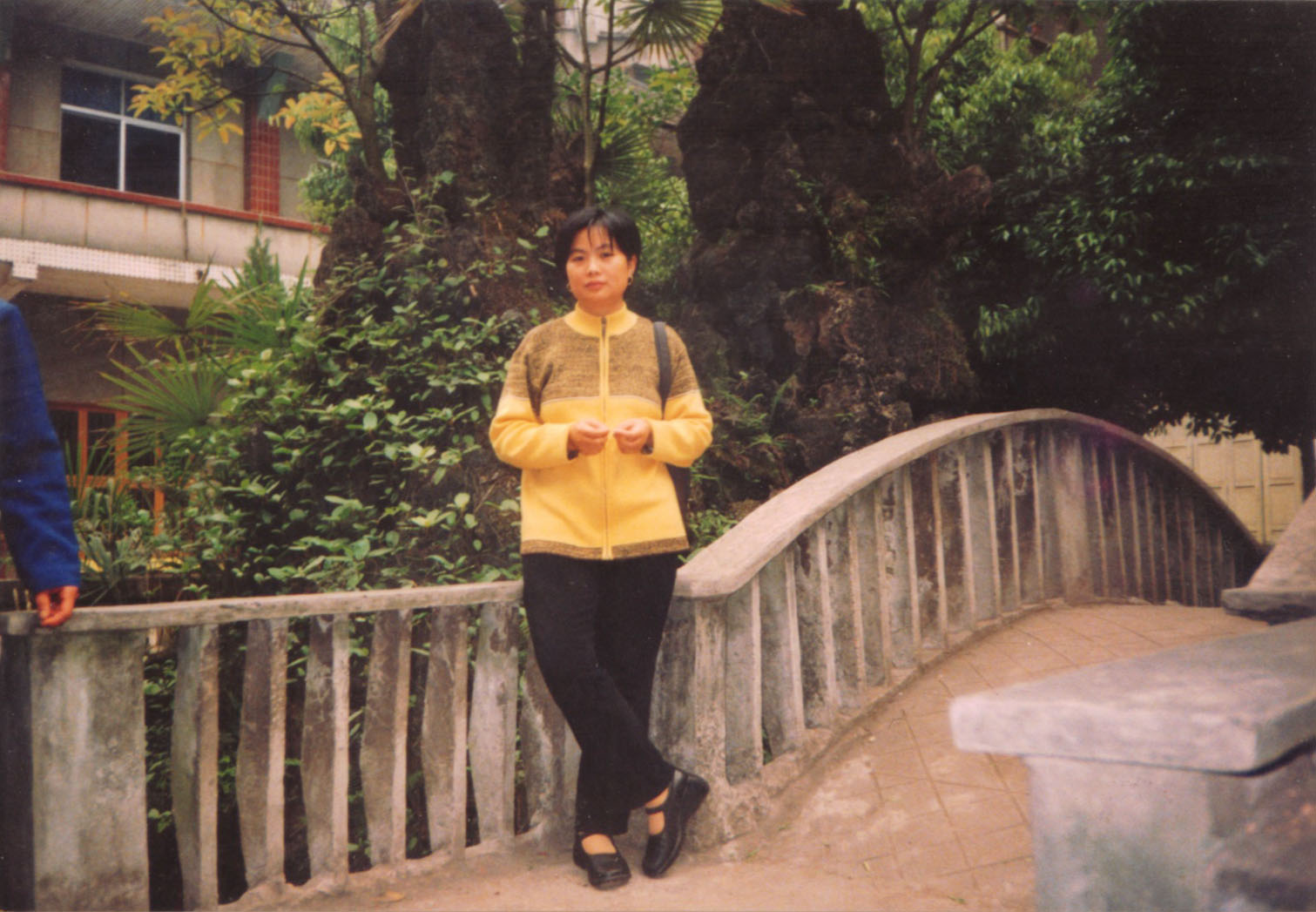

- Li Yan In Happier Times. Image Credit: Li Yan’s family

Read part one here.

On November 3, 2010, Tan was at home, drunkenly playing with an air rifle. When Li tried to stop Tan, he kicked her and threatened her with the rifle. Li seized the gun and struck Tan in the head twice, killing him. She dismembered his body, boiled the parts, and spread them around the village. She was arrested and sentenced to death by the Ziyang City Intermediate People’s Court. The judgment was upheld by the Sichuan High People’s Court after which it was sent to the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) in Beijing. The SPC confirmed the judgment in January 2013. Tan’s family successfully filed a civil suit against Li Yan’s family to pay 58,212 RMB in compensation – a large sum of money for Li’s working-class family.

Death sentences reviewed and confirmed by the SPC typically take place within days of SPC approval. By the time of our Hong Kong symposium, more than 13 months after the SPC decision, Li Yan had not yet been executed. Her plight had drawn domestic attention as Chinese feminists lobbied the government to stay its hand arguing it had not taken into consideration the violence Li had suffered. More than 400 Chinese lawyers and legal scholars had signed a letter to the SPC pleading for Li Yan’s life to be spared. The case was beginning to draw international attention too. Amnesty International initiated a global signature campaign calling for Li Yan not to be executed.

One of the SPC judges attending the symposium sat on an SPC panel reviewing death sentences, and it emerged that she was one of the judges considering whether to carry out the execution of Li Yan. At the end of the symposium, she thanked me for inviting her to the event, and told me that she had learned a lot from the discussion on domestic violence. “It has changed the way I think about it,” she told me. I stayed in touch with the Chinese participants, and on June 23, 2014, a Chinese official who had been at the symposium and was deeply concerned with Li’s case sent me a short email: “She has survived.” At the same time, Li Yan’s brother was advised that his sister’s death sentence had been overturned by the SPC. A retrial by the Ziyang City Intermediate People’s Court was ordered.

Dui Hua issued a press statement and sent it to journalists covering human rights in China, including many who were based in Beijing. Coverage in the international media was widespread, and the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva issued a statement applauding the decision.

One of the journalists I sent Dui Hua’s statement to was Didi Kirsten Tatlow, a New York Times journalist based in Beijing. Ms. Tatlow had been reporting on the Li Yan case since late 2012 and decided to travel to Chengdu and thence to Ziyang with photographer Gilles Sabrié to attend the retrial in November 2014. Outside the courthouse, she encountered an angry and threatening mob of Tan Yong’s family and friends. In a telephone call to me, Ms. Tatlow remarked that she had rarely welcomed the presence of Chinese police in her work, but she did on this occasion!

During the retrial, more evidence of domestic violence and testimonies from neighbors and witnesses emerged. Witness protection systems had to be set up to protect witnesses from Tan’s family. Inside the courtroom, the mob hurled insults and papers at Ms. Li and her lawyer. Five months later, on April 24, 2015, the court announced it had changed the judgment to death with two years reprieve, a unique Chinese sentence that almost always results in commutation after two years. On September 8, 2017, the intermediate court commuted the sentence and sentenced Li Yan to life in prison. Under Supreme People’s Court regulations that came into effect on January 1, 2017, Li Yan can be considered for a sentence reduction no earlier than September 2020. Her total time served after commutation cannot be less than 15 years, meaning that she will remain in prison until at least 2032, when she will be 62 years old.

- Tan Yong’s family confront journalists outside of the Ziyang Intermediate Court. Image Credit: Gilles Sabrié

- Relatives of Tan Yong called on the court to reaffirm Li Yan’s death sentence. Image Credit: Gilles Sabrié

“To Ziyang for Li Yan”

Didi Kirsten Tatlow

The reporting trip I made to Ziyang to attend Li Yan’s retrial was one of the most instructive, and frightening, moments of my 14 years reporting in China from 2003 until my departure for Berlin, Germany, in 2017. I had been reporting on women’s and feminist issues including gendered violence for years by the time the retrial was announced, including one heart-breaking magazine story for the South China Morning Post, my employer for the first seven years in China, about Sun Village, a home for children from abuse-filled families whose parents were both dead (often the father killed by the mother with rat poison after years of abuse by him), run by a former correctional officer from Xi’an. Strangely heartbreaking for me was the small fact that the children’s favorite TV show, SpongeBob SquarePants, was moved to late night viewing not long after my visit around 2006, on the grounds that it was an American show and would sully Chinese children’s minds. The kids had lost the cute little sponge and his pink friend Patrick Starfish, who made their often-harsh lives that bit more fun.

I applied to attend Li Yan’s retrial with low hopes – never had I been allowed to enter a Chinese courtroom and this was sensitive stuff. And initially I was put off by the Sichuan authorities, but always with the curious suggestion that I should try again later. I did, and on my third or fourth attempt I was given permission.

The experience was tough. In the small town of Ziyang Mr. Tan’s family seemed to be everywhere; the night before the hearing I met with members of Li Yan’s family in a restaurant, but we had to be careful not to speak loudly and her brother, Li Deshuai, though friendly and hospitable, was anxious. The next morning, I understood why. After handing over my reporter ID to the court front gate in order to enter the grounds, I went to talk to a large group of Mr. Tan’s family members that had gathered outside. They quickly grew hostile and began to pull at my clothes and arm, voices rising. His father waved his crutches at me; his sisters wagged their fingers in my face. Somehow, I was to blame, it seemed. Sensing things were slipping out of hand I moved into the court grounds and called for the police as the atmosphere deteriorated. They however were slow to react, and I wondered – if I, a foreign reporter with the backing of the court authorities to be present that day, could not get timely help from the dozens of court police standing around, how bad must it be for a Chinese, especially one with a grievance with the court?

Eventually the police did intervene. But Tan’s family persisted in their verbal and physical aggression, clearly hoping to influence the judges and the decision. I was shocked, too, that court officials did not order them out of the courtroom for contempt, as they sat there shouting and abusing Li Yan, telling her they hoped she would be raped for her crimes (her former husband had already done that, before she killed him.)

As a journalist, one rarely knows if or how one might have helped someone, though to me this was by far the most important aspect of the job. When John Kamm told me that he thought my work had helped I felt a deep sense of happiness. Li Yan was a petite woman standing alone in the courtroom between the panel of judges and shouting opponents, and I felt sorry for her, knowing also details of the appalling abuse she and her family had endured that had not been publicized out of consideration for the dignity and privacy of other family members (I also agreed not to publicize them, following their wishes.) It was a moment when I knew being a journalist was worth it, despite the strain, and regular fear, of reporting deeply not just on politics but also sensitive social issues like gender, in a complex, repressive and trigger-happy place like China.