EVENTS

Dui Hua’s Annual Year-End Event Returns

On December 9, Dui Hua held its first in-person event in almost two years. Prior to the pandemic, Dui Hua’s year-end dinner with supporters was an annual tradition. While a limited version was held online in 2020, this year’s event marked a cautious, optimistic return to person-to-person engagement.

Held at the Presidio Golf and Concordia Club in San Francisco from 5:15 to 8:30pm on December 9, Dui Hua staff was joined by local supporters, board members, participants from the International Symposium on Girls in Conflict with the Law (GICL), and community members from the Bay Area. All guests were required to show proof of vaccination. Masking and social distancing were practiced in all public areas.

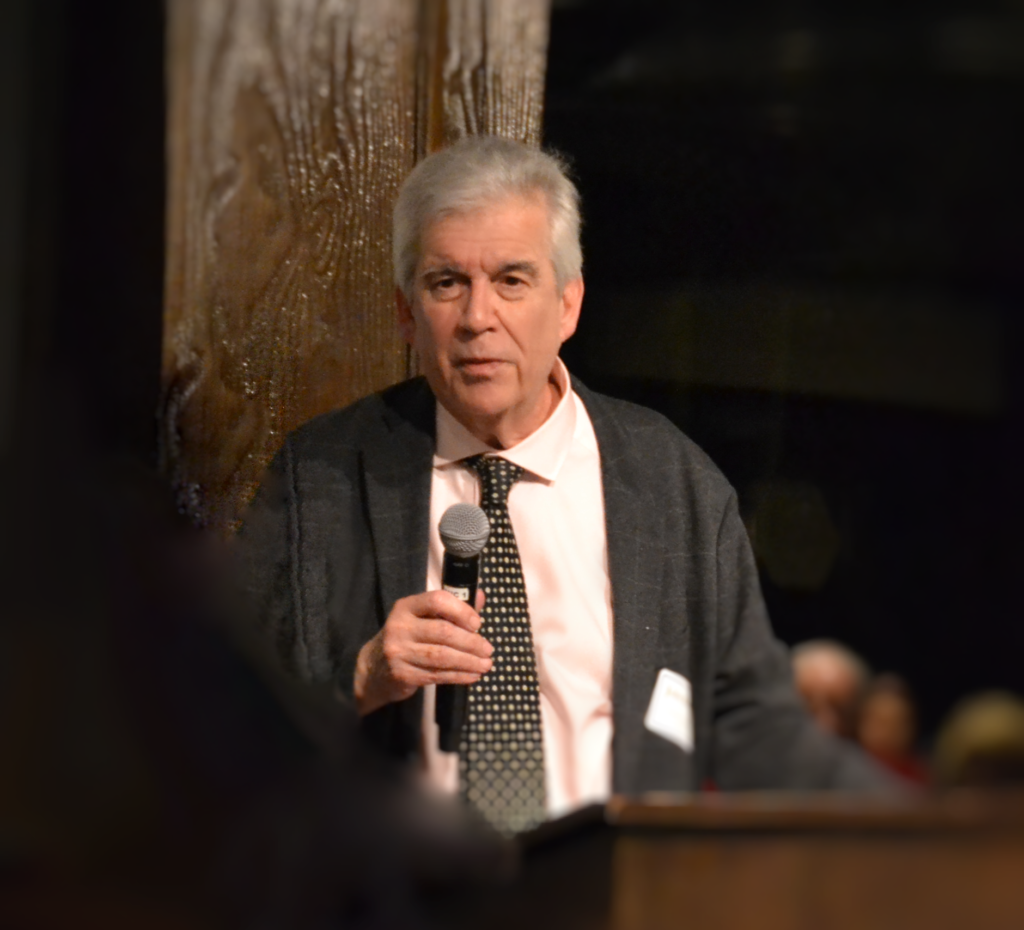

Board member Magdalen Yum introduced John Kamm, who spoke on Dui Hua’s challenges and achievements over the last year and through the pandemic. During the post-dinner program, Kamm invited Patricia Lee, Managing Attorney for the Juvenile Division of the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office and co-host of the GICL, to speak about juvenile justice reform. Lee went over the symposium and highlighted San Francisco’s success in reducing the number of girls detained in carceral facilities and the region’s efforts to prioritize diversion. She also spoke about the value programs like the GICL can have in effecting change locally, nationally, and, in the case of Dui Hua’s engagement with China’s Supreme People’s Court (SPC) and other experts and practitioners around the world, internationally.

Looking to the future, Kamm invited long-time Dui Hua ally Judge Leonard Edwards to speak about Dui Hua’s upcoming expert exchange: a webinar on child welfare laws involving Dui Hua and the SPC, currently slated for April 7, 2022. As Kamm explained, “China wants a child welfare law, and they came to Dui Hua. Then we went to Len Edwards. Len Edwards literally wrote the book on juvenile justice.” Edwards spoke about the value of child welfare and the need to ensure the best possible outcomes for at-risk youth through legal measures such as record sealing and placement for children with relatives in the social services system.

Throughout the evening, Kamm addressed attendees, providing a summary of the organization’s work over the past year and highlighting its achievements: continued dialogue with China despite the lack of international human rights dialogues, clemency for prisoners, engagement with the SPC, the GICL and developments in juvenile justice reform, unique research on religious freedom, and strong support from its donors, among others.

Challenges in the US-China context also merited discussion. Kamm went over the recent summit between the presidents of the two countries and pointed out that Taiwan dominated the discussion. At one point, Kamm held up an informal list of irritants featuring dozens of issues complicating US-China relations and Dui Hua’s work to advocate for prisoners.

The evening concluded with a Q&A session where guests posed questions to Kamm. Attendees asked about issues ranging from hostage diplomacy, Congress’ approach to containing China, the World Tennis Association’s response to Peng Shuai’s ordeal, and how both US and Chinese leaders are seeking to leverage domestic and international perceptions. Kamm’s comments reiterated the value of open, respectful, but accurate dialogue, at one point invoking the Chinese adage: “Your best friend is a critic.” Kamm spoke about cases Dui Hua is currently working on.

The return to an in-person event was welcomed by Dui Hua staff and supporters. Person-to-person engagement has long been a stalwart of Dui Hua’s work. Prisoner lists have traditionally been submitted in person, and in-person meetings with Chinese officials and representatives from other foreign governments have been crucial aspects to the foundation’s operations. In the summer of 2021, Dui Hua re-opened its San Francisco office in compliance with COVID-19 safety precautions, implementing a hybrid work schedule. While many NGOs shuttered their operations in Hong Kong, Dui Hua has maintained its presence.

This year-end event marks the latest positive step toward resuming meaningful dialogue and building a more stable future.

EXCHANGES

“Let’s talk about challenging and cooperating and competing on human rights.”

Since the International Symposium on Girls in Conflict with the Law’s (GICL) final webinar in April 2021, “Exchanges” has looked at the conditions girls face in detainment, the factors that lead them to crime, community-based solutions, the effects of discrimination, and China’s recent reforms. As 2021 ends and San Francisco prepares to close its juvenile hall, “Exchanges” ends by exploring best practices and recommendations from the GICL.

One of the most crucial steps to combatting child crime is understanding the economics behind it. Antonia Lavine, Coordinator of the San Francisco Collaborative Against Human Trafficking urged authorities to stop punishing sexually exploited girls and address root causes. “If you want to stop the market, you must make it not productive, you have to make sure that the benefit is outweighed by the danger of being prosecuted and by what you pay for the business to work.” California legislation like Senate Bill 1322 and San Francisco Penal Code Section 236.23 combat commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) by connecting victims with support services and recognizing the contexts in which offending by CSEC victims occurs.

Panelists extolled the virtues of using storytelling and art for advocacy. Photographer Richard Ross directs his work, such as side-by-side comparisons of facilities in Texan youth detention centers with military prisons like Abu Ghraib, to where policy makers work. “Getting the images into the hands of the right people to effect change is the battle that I do,” he said. During his presentation, Ross shared methods to combine visuals and text to maximize the impact of content.

Many panelists reiterated the value of storytelling, using narrative presentations to describe topics such as a girl’s journey through the justice system, a social worker’s typical day, and the unintended consequences of an anti-sexting law. But as Christa Big Canoe said, “It’s important to listen to stories, but we have to be able to actually create the change.”

The need for a “whole of society” approach recurred throughout the GICL. Judges Susan Breall and Roger Chan advocated for trauma-informed, survivor-centered approaches that keep non-violent offenders out of prison. Judge Jiang Jihai of China’s Supreme People’s Court lauded the values of context-based, interdepartmental juvenile justice legislation. Scotland’s “whole system” approach called “Getting It Right for Every Child” (GIRFEC) extolled the efficacy of community tribunals to identify context-based solutions for youth offenders. Panelists cited progressive measures in Denmark, where even violent offenders contribute to society, and Rwandan, where kinship is being integrated into rehabilitation, as innovative steps.

Patricia Lee, GICL co-partner and Managing Attorney for the Juvenile Division of the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office, presented on San Francisco’s plans to close its juvenile hall by December 31, 2021, making it the first metropolitan area to take such a measure. Lee noted that “…the eyes of other jurisdictions in California and, frankly, throughout the nation are looking at San Francisco to see if this is something that they can replicate.”

The closure aims to expand community-based alternatives to detention and provide rehabilitative non-institutional places of detention in court-approved locations, reinvesting the money saved to fund diversion programs. Closing the facility was motivated by financial, not humanitarian, reasons — a reminder that many juvenile justice laws are not just bad for human rights, they are bad for business: they disproportionately punish the vulnerable, encourage recidivism, strain underfunded services, and leave local communities with the socioeconomic consequences.

In 2014, Dui Hua co-hosted an exchange on the Bangkok Rules, or guidance for the treatment of female prisoners. GICL co-partner Taghreed Jaber of Penal Reform International noted, “If you ask me 10 years from the implementation of Bangkok Rules…as a practitioner in this field, I am a little bit disappointed. The number of girls who are coming in contact with the law and are in detention facilities is increasing.”

The GICL’s recommendations point to a better future for at-risk youth. Having led the UN Global Study on Children Deprived of Liberty, Manfred Nowak shared a unique set of guidelines for girls. On Hong Kong, Anna Wu renewed her call for the creation of a Children’s Commissioner. Finally, the GICL’s own list of recommendations offers pragmatic suggestions for everyone from practitioners to activists and concerned community members.

During a talk for the Asia Society in May, Dui Hua Executive Director John Kamm suggested that both China and the United States could rededicate themselves to the international order, including by rooting their juvenile justice systems in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which the United States has not ratified. “Let’s talk about challenging and cooperating and competing on human rights. Competition on human rights, not confrontation. If you want to make a difference, figure out a way to cooperate. I have done so. I know it’s possible.”

Visit GirlsJustice.org to learn more about the panelists, watch their individual webinars, download the annotated bibliography, and read a full list of recommendations.

PUBLICATIONS ROUND UP

Featured: Prisoner Updates 2021 #9, December 9, 2021

Dui Hua’s most recent Prisoner Updates installment reports on the formal arrest of labor activist Wang Jianbin (王建兵), Chen Yunfei’s (陈云飞) conviction and sentencing in Chengdu, and the latest legal obstacles in Xu Zhiyong’s (许志永) inciting subversion trial.

Read more here.

See also: Prisoner Updates 2021 #8, October 22, 2021: NGO activists admitted into prisons, labor activists missing; Lawyers avoid arrest for trial video release; unrelated charge suggested

DUI HUA IN THE NEWS

From time to time, Dui Hua Executive Director John Kamm speaks to members of the press on issues related to China and Dui Hua’s work.

In the latter quarter of 2021, media outlets have sought out Kamm’s insight as US-China relations dominated headlines. Kamm spoke to the Wall Street Journal on China’s new data restrictions, discussed factors affecting the cases of jailed Uyghur rights activist Huseyin Celil with Global News, and was quoted in Politico about the bipartisan congressional letter on behalf of arbitrarily detained US citizen Li Kai. Dui Hua’s research was also cited in the recently published Routledge Handbook of Chinese Citizenship.

JOHN KAMM REMEMBERS

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s human rights advocacy prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999.

Two Good Priests, Part II

Read Part I here.

November 1992 Trip to Beijing

I flew to Beijing on a Dragonair flight on November 16, 1992. I was picked up by an officer of my host organization, the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (CCPIT). After checking into the Great Wall Sheraton and taking the obligatory “rest,” I was whisked away to a welcoming banquet hosted by CCPIT Vice Chairman Xie Peijing at the nearby Kunlun Hotel.

The next five days were filled with meetings. I sat down for discussions with senior officials of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the State Council Information Office, the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations and Trade, and the Chinese People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs. Bill Clinton had just been elected, and his name was on everybody’s lips. They asked if I thought that Mr. Clinton would revoke China’s MFN status.

On Thursday November 19, 1992, I met with Wang Mingdi, director of the Ministry of Justice’s Laogai (Reform through Labor) Bureau (later renamed the Prison Administration Bureau). Wang gave me information on Li Fangchun. Li had been detained on February 23, 1983. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison for counterrevolution, reduced by one year in 1984 and one year in 1988. His sentence was to expire on February 22, 1993. No information was provided on any supplemental sentences including whether a sentence of deprivation of political rights had been imposed.

Wang didn’t mention that Father Li had already been released from prison on medical parole a short time before our meeting, in late October or early November 1992. He likely had not heard of the release, which suggested that the release had been sudden. Wang Mingdi would confirm the release at our next meeting in March 1993. Medical parole is the simplest way to secure an early release as it doesn’t need the approval of a court.

After briefing the American ambassador at his office in Beijing, I flew back to Hong Kong on Saturday, November 21. I got in touch with Father Politi and we agreed to meet at the Holy Spirit Centre in Aberdeen on Tuesday, November 24. There I told him what I had learned about Father Li Fangchun.

Politi activated the old PIME network in Kaifeng. He was told that the prison wardens had opened the prison gate and unceremoniously tossed Li Fangchun out onto the street around the time of my appeal to Minister Jin Jian. Li was found wandering the streets by a Catholic couple surnamed Cai, a priest and his sister, a Catholic nun.

Li was in bad shape. He could not remember his name, nor even remember that he had been a priest. He walked with difficulty. The couple nursed him back to health. He gradually recalled how he had suffered in prison; he had experienced two heart attacks.

Under Cover of Darkness

Politi travelled to Kaifeng in January 1993. He met Father Li at the couple’s house. After a period spent building trust, the Kaifeng priest, Politi, and Li Fangchun decided to leave Kaifeng early the next morning. A driver who could be trusted — probably a local Catholic — was hired, and at 5:00 AM, after a sleepless night, the group — Li, Politi, and Father and Sister Cai — left Kaifeng in the cold and dark. Politi was under surveillance. As he later put it, “In China, you learn to move under cover of darkness.”

The journey to Shangqiu from Kaifeng — 200 kilometers (about half the length of New York State) — took more than two hours on rough roads (this was long before a freeway was opened to link the two cities.) Father Li was mostly silent, tracking progress by ticking off the stones marking kilometers. Politi told him of our effort to secure his release. Li Fangchun wept.

His home village was about 20 kilometers from Shangqiu. As he approached it, he could see the spire of his old church. He called out for the taxi to stop, and he leapt from the car. As Politi put it, “he ran like a child” to the doors of his church. There he fell on his knees and kissed the earth. The church had long been abandoned; no priests were in sight. A villager, a Catholic, emerged from the shadows and led Father Li away, but not before telling Father Politi to leave right away and never come back. “It’s too dangerous for you, and for us.”

Not long after his return to Hong Kong, Father Politi was recalled to Italy. Those in the local Catholic community believed he was called back in part due to his activism on behalf of Catholic bishops and priests in China, including his trips to the mainland to gain information on local Catholic communities and imprisoned Catholics. Beijing was also said to be angered by Father Politi’s role in leaking photographs of the deceased Bishop Fan Xueyan, lying on a slab. The photos suggested that Bishop Fan, his body covered with bruises, had been mistreated.

Politi’s last trip to the mainland was the one he made to Kaifeng in January 1993 to bring Li Fangchun home to Shangqiu. Shortly after his return to Hong Kong and as he was preparing to return to Milan, Father Politi learned that Li Fangchun had died from his third heart attack.

The Italian missionary never returned to Hong Kong, working in Milan on China issues until he passed away at the age of 75 from complications from a long illness in December 2019. Father Politi gave an on-camera interview to my son Rene and his Oberlin College classmate Jake Hochendoner in October 2013. Much of the information on Politi’s trip to save Li Fangchun comes from that interview.

Father Politi is remembered as a good shepherd by Catholics on the mainland and in Hong Kong, where he served as a parish priest in Yuen Long and Tsuen Wan before taking up his position at PIME House in 1986. He fought to save the Roman Catholic Church from extinction in China during the darkest days of the second half of the 20th century. He will long be remembered.

Subscribe if you want to receive Dui Hua publications by email.