EVENTS

Dui Hua’s Deep Ties to Hong Kong Reflect Years of Engagement

The Dui Hua Foundation has enjoyed long and enduring ties with Hong Kong for many years and is deeply concerned by the turmoil engulfing the city.

Dui Hua Chairman and Executive Director John Kamm served as president of the American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) in Hong Kong in 1990. As president, he testified to Congress three times that year, opposing revoking China’s Most Favored Nation (MFN) trading status in large part because removing the status would greatly harm Hong Kong, still reeling from the shock of the events of June 4, 1989 in Beijing.

Kamm arrived in Hong Kong in August 1972. It was his home for the next 23 years. He married and his two sons were born there. He launched a successful business career and became involved in human rights while living in Hong Kong.

In November 1990, Kamm spoke to the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations at the Harvard Club in New York City. In his last public remarks as president, he gave a speech entitled “Towards a Hong Kong Policy.” It advocated legislation to protect Hong Kong’s special status under United States law and was the first time a public figure spoke out on the need to enshrine Hong Kong’s status by an act of Congress. Kamm’s speech eventually found its way to senior staff of Senator Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky). At the time, McConnell was finishing up his first term as a United States senator. He was reelected in November 1990 and has been reelected to the Senate five times. He is currently Majority Leader of the Senate and faces reelection in 2020.

McConnell introduced the Hong Kong Policy Act, which was passed by both houses of Congress in 1992. The Act granted Hong Kong separate status for trade, immigration, and access to technology. It also required the Department of State to report on whether Hong Kong continues to enjoy the high degree of autonomy promised by the Basic Law and the Sino-British Joint Declaration.

The Hong Kong Policy Act remains relevant to the current day: despite a raging trade war between the United States and China, Hong Kong products are not subjected to higher tariffs. It continues to enjoy the lowest tariff rates posted in the United States Harmonized Tariff Schedules. And it continues to enjoy special status on technology access and immigration.

The United States Congress is now debating the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, championed by Senator Marco Rubio (R-Florida) and supported by a large group of bipartisan lawmakers in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. It differs from the Hong Kong Policy Act in at least one important way: it imposes sanctions on Hong Kong officials involved in human rights abuses, including extraditing Hong Kong people to China. Speaker Nancy Pelosi intends bringing up the act for debate and voting after Congress returns from its summer break in September.

Dui Hua established an office in Hong Kong in 2007. The office is manned by three staff, including research manager Luke Wong, and it makes significant contributions to Dui Hua’s advocacy, research, and publications work. Dui Hua Director Tom Gorman lives in Hong Kong and Director Magdalen Yum and Chief Operating Officer Irene Kamm were both born in Hong Kong. Both have many relatives in the former British Colony, which became the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China in 1997.

In 2014, Dui Hua, together with the University of Hong Kong Faculty of Law’s Centre for Comparative and Public Law, London-based Penal Reform International, and Renmin University of China Law School in Beijing, organized an international symposium on women in prison and the Bangkok Rules in Hong Kong. The symposium, which was generously supported by the governments of the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland and the Ford Foundation, brought together 25 expert presenters from nine countries, including China, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and the International Committee of the Red Cross. The symposium consisted of two days of discussions on issues facing women in conflict with the law followed by a full day visit to a large women’s prison.

Reflecting Hong Kong’s continued importance as a place where the international community can exchange ideas and best practices on issues of social justice, Dui Hua and partners will stage an international symposium on girls in conflict with the law in April 2020.

Although Dui Hua Executive Director returned to the United States in 1995 to settle in San Francisco, site of the foundation’s head office, he returns to Hong Kong at least twice a year to meet with local and Chinese government officials, NGO representatives, foreign diplomats, scholars, journalists and business leaders. Kamm intends to visit Hong Kong later this year to assess the current situation and push forward plans for next year’s International Symposium on Girls in Conflict with the Law.

PRISONER UPDATES

Tianjin Response

In July, Dui Hua received a response from a reliable source on a request for information on prisoners in Tianjin. The response revealed that Zhou Shifeng (周世峰) is due for release on September 24, 2022. Zhou, a founder of the Beijing Fengrui Law Firm who was detained during the “709 crackdown” in 2015, was convicted of subversion and sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment by the Tianjin Number Two Intermediate People’s Court on August 4, 2016. Upon completion of his prison sentence, Zhou will be subject to a five-year deprivation of political rights (DPR), a sentence which entails surveillance and bars him from giving interviews, publishing articles, and standing for election. The same response confirms the release date for the veteran dissident Hu Shigen (胡石根). Convicted for subversion along with Zhou, his sentence is due to expire on March 26, 2023. The response also confirmed that Liu Yong (刘镛), convicted for illegally procuring or trafficking in state secrets for foreign entities, will serve four years of DPR after completing his sentence of eleven years on April 10, 2024.

The response also provided updates for prisoners convicted of “organizing/using a cult to undermine implementation of the law.” Two of these prisoners who received clemency are Falun Gong practitioners. Liu Hong (刘红) was released from Tianjin Women’s Prison on February 7, 2019, after her seven-year prison sentence had been reduced by eight months. Wang Shulin (王树林), who is serving his seven–year–and–six–months’ sentence in Binhai Prison, is due for release in December 2020, following a nine-month sentence reduction he earned in January 2019.

The response also confirmed that Lü Guifen (吕桂芬), another female Falun Gong practitioner, is currently confined in Tianjin Xinsheng Hospital, while serving her eight-year prison sentence. The response, however, did not provide information on her health status. She is due for release from Tianjin Women’s Prison in March 2020.

Recent Updates

Huang Qi (黄琦), who was accused of running a “hostile foreign website,” named 64tianwang.com (六四天网) to commemorate the June 4, 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, received a harsh sentence of 12 years’ imprisonment in Mianyang, Sichuan, on July 29, 2019, for two offenses: intentionally leaking state secrets and illegally providing state secrets to foreign personnel or organizations. Friends and his 86-year-old mother worry that Huang will suffer the same fate as Nobel Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo (刘晓波), who died in custody in July 2017 after being denied leave to seek cancer treatment overseas. Huang, aged 56, is scheduled for release on November 27, 2028. He is reportedly suffering from chronic diseases such as renal failure, hydrocephalus, heart disease, and emphysema.

Three notable activists were released in August 2019. Lin Zulian (林祖恋), an iconic figure of the 2011 Wukan protests against corruption and land seizure, was released from Guangdong’s Yangjiang Prison on August 3. The popularly elected village leader was once hailed by state media for creating a democratic mechanism that peacefully resolved a growing number of rural disputes across China. This mechanism came to be known as the “Wukan Model.” Lin continued his efforts to organize petitions to seek redress for land disputes, leading to his arrest and televised confession for taking bribes in June 2016. Three months later, the Chancheng District People’s Court sentenced him to a 37-month term of imprisonment on September 8. Lin, now aged 75, has been under 24-hour police surveillance since his release.

Also on August 3, Dong Guangping (董广平) completed his three-years-and-six-month sentence at Nan’an District Detention Center, Chongqing, given for subversion and illegal border crossing. After fleeing to Thailand in September 2015, Dong awaited resettlement to Canada as a refugee, as recognized by the U.N. on account of a well-founded fear of persecution if he returned to China. His forcible repatriation by the Thai government in November 2015 drew strong criticism from the U.N. Human Rights Council and international rights groups. Dong was arrested in China for commemorating “June Fourth” in May 2014 but fled eight months later with his wife and daughter, while he was on bail and awaiting trial. In 2001, he was imprisoned for three years by the Zhengzhou Intermediate People’s Court for the inciting subversion. He publicly called for political reform and rehabilitation of “June Fourth.”

Yang Maodong (杨茂东), also known as Guo Feixiong (郭飞雄), was released from Guangdong’s Yingde Prison on August 7, after serving six years in prison for “gathering a crowd to disturb a public place” and “picking quarrels and provoking troubles.” Guo was a vocal supporter of the now-defunct New Citizens Movement and Southern Street Movement, which both called for the disclosure of officials’ private assets.

PUBLICATIONS ROUND UP

Featured: Human Rights Journal: August 21, 2019: Fortifying the Great Firewall: The Criminalization of VPNs, Part II

In “Fortifying the Great Firewall”, Dui Hua looks at the various cases where internet users were criminally punished for using unauthorized VPNs (Part I), and examines the crackdown on providers of VPNs (Part II).

In 2017, a series of criminal cases against VPN providers and users began to surface after the Ministry of Industry and Information instituted VPN restrictions earlier that year in accordance with the Notice on Cleaning Up and Regulating the Internet Access Service Market. In these cases, authorities invoked the offense of “illegally providing a tool for intruding into a computer information system.” In a legal opinion column published in October 2018, China University of Political Science and Law Professor Luo Xiang) likened the offense to the now-abolished crime of “hooliganism” (liumangzui 流氓罪), calling it “cyber hooliganism” (jisuanjiliumangzui 计算机流氓罪), because it is increasingly being misused by law enforcement, as hooliganism once was, and is raising what Luo sees as “similar challenges.”

Prior to its abolition in the 1997 Criminal Law, “hooliganism” was used as a catch-all offense based on weak legal logic that gave authorities discretion to punish a broad range of vaguely defined crimes. Luo uses the term cyber hooliganism as an analogy, to imply that the offense of illegally providing a tool to intrude into computers has become a new “pocket crime” (kou daizui 口袋罪). Such ill-defined offenses can all too easily be used, especially by police, to criminalize cyber activities, even those which “no explicit stipulations of law deems (sic) a crime,” and for which, according to Article 3 of the Criminal Law, they should not “be convicted or given punishment.”

An additional reason for concern is that the offence of using VPNs, which is now incorporated as Article 285 of the Criminal Law, is applicable in a broad range of circumstances, when an offender violates a decision or law formulated by the National People’s Congress (NPC) and its Standing Committee (SC), or even an administrative regulation, measure, or order issued by the State Council. In addition, the offense has been widely used even when an individual does not engage in any of the aforementioned cybercrimes: VPN providers are prosecuted simply for violating the 2017 VPN ban, an administrative notice by the Ministry of Industry and Information. As the VPN ban was not formulated by the State Council, however, violating this administrative measure should not incur criminal liability under Article 96 of the Criminal Law.

Continue this story here, or read Part I here.

JOHN KAMM REMEMBERS

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s human rights advocacy prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999.

The Execution of Wo Weihan

In November 2008 I traveled to the New Jersey shore, where I had grown up. My youngest son, Rene, was with me. We would celebrate Thanksgiving dinner with my brother and his family, and, before leaving the family to return to San Francisco, scatter my mother’s ashes. She had died the previous July, the wife of three World War II veterans. I was with her when she died in a Florida hospice, and I had pledged to scatter her ashes in the place she loved best, off Avon beach, where she had met my father.

The dinner on November 27 was joyous and traditional, turkey with all the trimmings (including copious amounts of the family’s special stuffing), but it was a time of hope as well. Wo Weihan (沃维汉), someone facing imminent execution in China whose case I’d been working on, had met with his family at a detention facility in Beijing, and they had been told by way of the Austrian Embassy that another family visit could take place the next day. When I heard this news, I allowed myself to think that his execution might still be stayed. This extension, if granted, would be beyond the limit for delaying an execution approved by the Supreme People’s Court.

There were many reasons to stay this execution. Perhaps someone in a position of power would realize how this arbitrary, cruel, and unusually extreme punishment would impact China’s relationships with foreign countries and its international image, not long after the positive reaction to the 2008 Olympics.

After dinner, Rene and I drove to our hotel, the Courtyard in Wall Township, where we shared a room. My sleep was fitful. I sensed another person in our room, wandering aimlessly about. In my dreams I saw a ghostly apparition.

Just after 6 AM, my phone rang. It was my colleague Josh Rosenzweig, calling from Hong Kong. Wo Weihan had been executed earlier that day, when it was still Thanksgiving in the United States. Josh asked if I’d give an interview to The Washington Post. I said yes, in 10 minutes. I threw on my clothes and went down to the lobby and then outside where it was cold and foggy. The call came in to my cell phone. The journalist wrote that I reacted with anger and disbelief: “’I have been doing this work for 19 years, and this is the absolute lowest point of those 19 years,” Kamm said. “I am devastated.’”

A Scientist and Entrepreneur

Wo Weihan, a Chinese citizen born in 1949 in Heilongjiang Province, was an accomplished scientist who held several patents. He had founded a biochemical company in Beijing upon his return from studying and working in Germany and Austria, where he lived for several years in the 1990s, and where his two daughters, Ran and Di, live. Wo Weihan was a civilian who had never served in China’s military. His daughters are Austrian citizens. Wo was also a member of the Daur ethnic minority, one of China’s smallest ethnic groups. He had had the opportunity to apply for Austrian citizen but had turned it down. He was proud of his Chinese origins.

In 1984, the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party issued Document Number Five, which set out the principle of “Two Restraints, One Leniency” that was to be applied to ethnic minorities. Law enforcement was to be lenient to offenders from ethnic minorities by making fewer arrests and handing down fewer executions. Executions of ethnic minorities in China were rare at the time of Wo Weihan’s execution. Executions of Uyghurs accused of terrorism-related crimes have taken place in recent years. Executions of members of other minorities remain rare, however. The only known execution of a Tibetan sentenced to death in recent years was that of Lobsang Dhundop, a nephew of Tenzin Delek Rinpoche. He was executed in 2003 after being convicted of involvement in a series of bombings. In 2005, an official of Manchu ethnicity, Tong Daning (佟达宁), was sentenced to death and subsequently executed for spying for Taiwan.

Rarer than executions of members of ethnic minorities are executions of civilians for espionage, as opposed to executions of military officers and government officials. That remains the case in China today. Dui Hua is not aware of an execution of a civilian for espionage since 2000 – with the notable exception of Wo Weihan.

Wo was taken into custody on January 19, 2005 and placed under residential surveillance in a designated location. Shortly thereafter, Guo Wanjun (郭万钧), said to be a distant relative of Wo who worked as a missile expert for a research institute affiliated with the Chinese air force, was taken into custody and placed under residential surveillance in a designated location as well. Both men were taken into custody on suspicion of committing the crime of espionage, a crime of endangering state security that carries the maximum sentence of death.

Not long after being placed under residential surveillance in a designated location, Wo Weihan suffered a stroke, possibly due to mistreatment by his captors. He was granted bail to return to his home to recuperate. Granting bail to an individual accused of a crime that carries the death penalty is highly unusual.

Wo was formally detained on March 30, 2005, accused of spying for Taiwan. He was put in the hospital ward of a state security detention center. He was formally arrested on May 5, 2005. Only after his arrest was Wo allowed a visit by a lawyer; it took place 10 months after his initial detention. Family visits were not permitted until the day before he was executed.

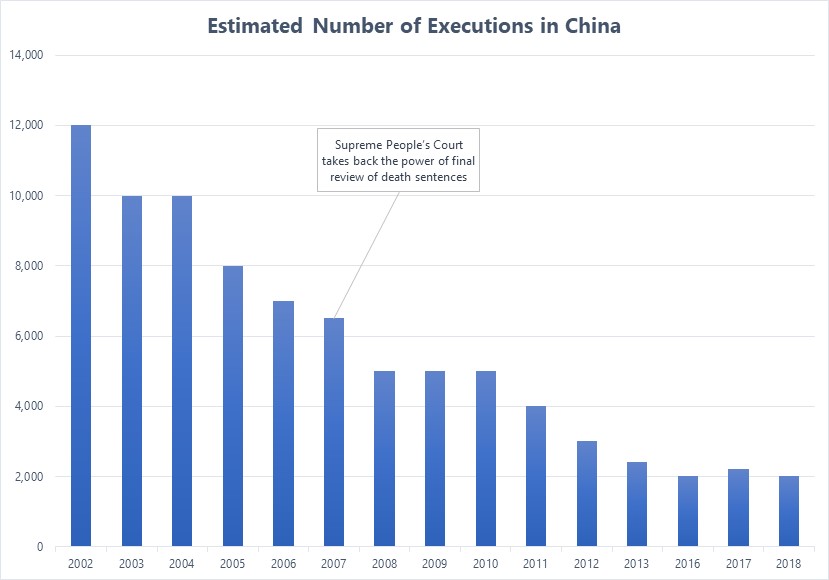

The Supreme People’s Court (SPC) took back the power of final review of death sentences on January 1, 2007. Under pressure from China’s senior leaders, it had delegated this power to lower courts in 1984 at the height of the first “Strike Hard Campaign.” Upon taking back the power of final review, the SPC declared that, henceforth, only the most “vile and serious crimes” would attract the death penalty. In the first year of conducting reviews, the court overturned 15 percent of death sentences.

On May 24, 2007, Wo Weihan and Guo Wanjun were tried by the Beijing Intermediate People’s Court. The two men were sentenced to death in a closed trial. The prosecution introduced a confession from Wo that had been given in the ten months he was denied a lawyer; Wo recanted the confession made under duress without a lawyer present. The court had determined that Wo and Guo had provided Taiwan military intelligence with top secrets but provided few actual details. It was alleged that Wo had provided photocopies of a missile defense system and information on the health of a senior official who was not identified. (According to Wo’s lawyer, the photocopies in question were from an article in a publicly available journal that was subsequently classified.) Providing these secrets apparently constituted a “vile and serious” crime deserving the ultimate penalty.

The Taiwan intelligence agency to which secrets were provided turned out to be the “Grand Alliance for China’s Reunification under the Three Principles of the People,” a Taiwan-based non-governmental organization that promoted Dr. Sun Yatsen’s political philosophy and Chinese culture. It had no known links to Taiwan’s intelligence agency. The group’s contact details had been found in Wo’s diary.

Dui Hua Gets Involved

Dui Hua began working on Wo’s case in January 2008, when Josh Rosenzweig was visited in his Beijing hotel room by Wo’s daughter Ran Chen and an officer of the European Union (E.U.) Mission in Beijing. Josh offered advice and assistance. He was told that, for the time being, the family had decided, on the advice of Wo’s lawyer and the Austrian Embassy in Beijing, to keep a low profile and avoid media coverage.

The Chinese government was preparing to host the Summer Olympics in August 2008. In March 2008 protests erupted in Tibet; they were put down by Chinese police and troops. The world reacted in outrage. The Olympic torch run was beset by protests. On March 26, French President Nicolas Sarkozy suggested that he might boycott the Olympics opening ceremony in Beijing. Not long afterward, American President George W. Bush announced that he would attend the ceremony, and other world leaders fell into line. Beijing was very grateful to President Bush.

On March 28, 2008, the Kuomintang’s candidate for Taiwan president, Ma Yingjeou, won the presidential election. He succeeded Chen Shui-bian, seen by Beijing as a dangerous advocate of Taiwan independence. Ma’s election ushered in an era of good will between the Mainland and Taiwan that would be put at risk if China executed a civilian for allegedly spying for Taiwan.

A day later, on March 29, 2008, Beijing’s High Court rejected the appeals of Wo Weihan and Guo Wanjun. The death sentences were upheld. The cases were sent to the Supreme People’s Court for final review.

After Wo’s appeal was rejected the family decided to step up its effort to save him. I traveled to Beijing, and on April 2, 2008, I met Ran and her husband Michael in my room at the Beijing Renaissance Hotel. Ran, who had just enrolled as an MBA student at the University of California, struck me as an intelligent and courageous young woman determined to do what was necessary to save her father. Michael, an American citizen, was equally determined to fight for his father-in-law’s life. We mapped out a strategy and decided on the role I and Dui Hua would play.

Dui Hua’s advocacy would involve the following:

- Raise the profile of the case in international media and alert other human rights group of Wo’s possible execution;

- Push the United States government to aggressively lobby the Chinese government to grant clemency to Wo Weihan; and

- Use Dui Hua’s extensive contacts with China’s judicial and foreign affairs establishments to advocate for the overturning of Wo Weihan’s death sentence.

Press Conference

On April 3, 2008, I summoned Beijing-based journalists to come to my hotel for an impromptu, unsanctioned press conference on the Wo Weihan case. The hotel management became agitated and tried to stop the journalists from taking the elevator to the seventh floor, where I had been given a junior suite. In response, journalists walked up the stairs, lugging their heavy equipment with them.

At least two dozen journalists from outlets in 10 countries in Latin America, North America, Europe, and Asia attended. I went over the basics of the case and listed the reasons I felt clemency should be granted: the need to project a humane image for the Olympic games; weak evidence and violations of due process rights; the Supreme Court’s overturning of hundreds of death sentences; Wo’s status as a member of an ethnic minority; the fact that executions of civilians for espionage were extremely rare; the prospect of improved relations with Taiwan, on whose behalf Wo allegedly spied.

Articles in papers from Brazil to Austria to Japan began appearing the next day. At the same time, Ran and Michael were giving impassioned interviews to major outlets, including the BBC. Never before had there been so much coverage of an imminent execution in China, the world’s top executioner.

Engaging the American Government

My close friend Clark “Sandy” Randt was American ambassador to China. Sandy and I knew each other in Hong Kong, where we were both heavily involved in American Chamber of Commerce activities; our children grew up together. He proved to be an invaluable resource in the doomed fight to save Wo Weihan.

Sandy Randt was also a close friend of President George W. Bush. The two men had attended Yale together, and after he was elected President Bush chose Sandy as America’s ambassador to China. After taking up his position in 2001, he went on to serve with distinction – he was an outspoken advocate for human rights – stepping down at the end of President Bush’s term of office as the longest serving American ambassador to China in the history of relations between the two countries.

On April 8, 2008, Ambassador Randt raised Wo’s case with China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In the months that followed, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Assistant Secretary of State David Kramer, as well as other officials and members of Congress asked the Chinese government to grant clemency to Wo Weihan.

David Kramer’s role was especially important. He was the Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights, Democracy, and Labor, in which position he was the ranking official tasked with managing the bilateral human rights dialogue with China. After a hiatus of six years, the two countries agreed to hold a round of the dialogue in Washington May 24-28, 2008. Wo Weihan’s name was placed on the list of priority cases that Dui Hua helped draw up. It was accepted by the Chinese representative.

Lobbying the Chinese Government

Unique among human rights groups working on China, Dui Hua maintains open channels of communication with the Chinese government. I decided to bring these into play in the effort to save Wo Weihan’s life. I sent emails to, and met privately with, Chinese foreign affairs and judicial officials.

I concentrated on the SPC, which had been tasked with reviewing Wo’s death sentence passed by the Beijing High People’s Court. Dui Hua had an especially good relationship with the SPC; we had invited them to visit the United States to study the American juvenile justice system in October 2008.

In September 2008 I traveled to Beijing to meet with two senior judges to make final arrangements for the delegation to the United States the next month. I turned the conversation to Wo Weihan and explained that I was a friend of the family. I pointed out that executions for espionage in the United States were very rare. The last time civilians were executed for espionage – Ethel and Julius Rosenberg – was in 1953. Now the trend for the most serious such offenders is a sentence of life in prison.

The senior judge present nodded his head. He had been to Florence Super Max in Colorado and saw the tough conditions “lifers” faced there.

I criticized the lack of detail in the court judgments and queried how someone facing a death sentence could be allowed home to recuperate from an illness. I asked the judge when the SPC would complete its review. He replied that most reviews are completed within six months of the High Court decision. He cautioned that the number of death sentences overturned thus far in 2008 was far fewer than in 2007. He assigned a colleague to be my liaison on the case, but as it turned out the man proved to be of no use.

Family Told to Visit Wo

On the evening of November 17, 2008, Wo Weihan’s wife received a call from the SPC advising her to file an application, with supporting documents, to visit Wo Weihan. The application was to be filed within seven days, and if approved, the family should make the visit as soon as possible. The family’s lawyer saw this as a bad sign: the SPC had approved the execution. Preparations to execute Wo Weihan were underway.

I took action as soon as Ran advised me what happened, sending urgent messages to the Chinese Embassy in Washington, the Chinese Mission in Geneva, the SPC, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, and academic and research organizations under the control of the Chinese government and Communist Party.

Complicating Factors

The responses I received were troubling. The Chinese embassy response was terse: the case would be handled in accordance with the law. My liaison at the SPC, which we had just hosted in the United States, washed his hands of the matter. A friend at the Chinese mission in Geneva advised that her ambassador would try to help – in fact he did try, telling me he had sent recommendations to his superiors in Beijing — but warned, somewhat ominously, that the sharp criticism of China’s capital punishment by the just-concluded meeting of the United Nations Committee Against Torture was deeply resented by Beijing: “Therefore it might be bad timing for the West to seek reconsideration of the case.”

Another complicating factor was the unraveling of relations between China and the European Union, which had actively lobbied the Chinese government to grant clemency to Wo Weihan, the father of two E.U. citizens. France, which held the rotating presidency of the E.U., had already drawn the ire of the Chinese government over President Sarkozy’s suggestion that he might boycott the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games.

On August 22, 2008, Sarkozy’s wife, Carla Bruni, joined the Dalai Lama at the inauguration of a Buddhist temple in France. There was speculation that Sarkozy himself would meet the Dalai Lama when the Tibetan spiritual leader visited Europe later in the year. When it became clear that the meeting would indeed take place, China canceled the E.U.-China Summit, shocking E.U. leaders and diplomats.

Nevertheless, E.U. officials traveled to Beijing to take part in the E.U.-China human rights dialogue that opened in Beijing on November 25. It was to run until November 28. The fact that Beijing declined to cancel the dialogue raised hopes that damage from the fracas over the impending Sarkozy-Dalai Lama meeting could be contained.

The Family Visits Wo Weihan

On Tuesday, November 25, Ran Chen received a call from the Beijing Intermediate People’s Court Number Two. The caller advised Ran that the SPC had confirmed the death sentence on her father and told her to come to the court at 9 AM on Thursday November 27 to see her father for what would turn out to be the last time. Ran arrived at the court at the appointed time. Wo’s wife, Ran’s stepmother, arrived and together the two women were taken to a small room. They sat on one side of a glass partition. Wo was brought in, flanked by two guards.

Wo was surprised to see his visitors. He had no idea that he would soon be executed. He was optimistic that the SPC would overturn the death sentence and expressed confidence in China’s justice system. Ran and his wife read letters from his brother and his wife, and told him that his youngest daughter, who was nine or ten at the time, was doing fine. Wo teared up at the mention of a child he’d never see again.

The tension proved too much for Ran. “This is a terrible injustice. China has a broken justice system and you are a victim of it,” she cried. One of the guards standing behind her reproached her, saying she had no right to criticize the Chinese government and its justice system. Ran shot back. “Why not? I have every right to do so.” At this point Wo Weihan intervened and asked his daughter to calm down.

The meeting lasted 30 minutes. Ran and her stepmother left the room, sobbing. None of the court officials dared to look at them. They returned to a friend’s apartment where they were joined by Di, Wo’s oldest daughter, who had just arrived in Beijing. They held each other and sobbed for a long time. Later that afternoon they received a call from the Austrian Embassy. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) had told the Austrians that the execution would be put off to allow for Di to visit her father the next day.

Execution and Aftermath

That visit would never take place. On the morning of November 28, 2008, as the E.U.-China human rights dialogue was winding down, Wo Weihan and Guo Wanjun were executed by gunshots to the back of their heads. They were promptly cremated. That afternoon the MFA told the Austrian Embassy that the execution had taken place that morning. Senior E.U. officials were still in Beijing.

The response from the E.U. was swift. A statement was issued. “The E.U. condemns in the strongest terms the execution of Mr. Wo. It deeply regrets the fact that China has not heeded the repeated calls for the execution to be deferred and for the death sentence to be commuted. It wishes to express its indignation at this execution which comes just after the conclusion in Beijing of the E.U.-China human rights dialogue.”

Austria’s Foreign Minister Ursula Plassnik used even stronger language, saying that the execution “must be considered an intentional affront to the E.U.… China’s approach emphasizes the ruthlessness and coldness of the SPC’s decision.”

Countries weighed in, including the United States, sharply condemning the execution. Human rights groups, including Amnesty International, likewise expressed outrage. Calls were made for the human rights dialogue between China and the E.U. to be permanently cancelled. It has in fact continued to take place every year.

I received a message from a Chinese official, a leading reformer and opponent of the death penalty: “Today I am ashamed to be a Chinese official!” China’s media tried to justify the execution, but China Daily, in a rare admission, noted that the execution had stirred resentment of China in certain countries.

Wo Weihan is Buried

Five days after the execution, the family retrieved Wo Weihan’s remains. They had selected a burial plot at Badaling Cemetery, a peaceful place a mile away from the Badaling Great Wall. They went to the cemetery to purchase the plot, but as the paperwork was being filled in, a manager appeared and told them they would not be permitted to buy the plot, apparently because it would contain the remains of an executed “criminal.” Ran once again exhibited her fearlessness. She accused the manager of being a coward and threatened to call the international press and file a lawsuit if the cemetery refused to let the family purchase the plot. Chastened, the manager backed down and the transaction was completed. Eventually the family bought two other plots for Wo’s father and mother, who were buried in Heilongjiang. The parents and their son were reunited in death.

Wo Weihan’s funeral took place on December 6, 2008. Family members and representatives of the Austrian Embassy attended. It was a moving memorial, a tribute to an extraordinary man who was loyal to family and country.

In December 2008 I went to New York to meet with a Chinese diplomat with whom I had worked on sensitive cases. He tried his best to convince me that the execution of Wo Weihan was justified, providing details of the other secrets Wo allegedly gave to Taiwan. I would have none of it. I told him that I would continue Dui Hua’s work on behalf of prisoners, at the family’s request. He seemed relieved that I would do so.

Today the execution of Wo Weihan, nearly 11 years ago, has largely been forgotten. A blip on the screen of the history of E.U.-China relations on human rights, even less of a blip in the history of U.S.-China wrangling over human rights.

But, as in the case of the Rosenbergs, the international and to some extent domestic outrage seems to have had an effect. Support for capital punishment in China is still strong among the Chinese population, but it has waned. Calls for its abolishment have gained strength among reformers.

Since the execution of Wo Weihan, the number of executions in China has dropped sharply from around 7,000 in 2007 to around 2,000 in 2018, according to Dui Hua estimates. In 2019, 46 crimes carry the death sentence, down from 68 in 2008. There has not been an execution of a civilian for espionage in China since Wo Weihan’s. Nor has there been an execution of a member of an ethnic minority group for the crime of espionage.

Such is the legacy of Wo Weihan, an extraordinary man forgotten by all but his family and those who worked to save him from execution. His brother still visits the place where Wo Weihan and his parents are buried, laying flowers and saying prayers for the repose of their souls.