EVENTS

Dui Hua and Supreme People’s Court Hold Dialogue on Child Welfare Laws

On Thursday, April 7, 2022 (in San Francisco), Friday April 8, 2022 (in Beijing), Dui Hua hosted a virtual expert exchange on child welfare laws with China’s Supreme People’s Court (SPC). The event, believed to be the first exchange on child welfare laws in the two countries, marks the eighth juvenile justice collaboration between Dui Hua and the SPC.

During the event, which was hosted by Dui Hua Executive Director John Kamm, legal experts from the United States and China shared best practices and policies on legal protections for children in their respective countries. Retired Judge Len Edwards moderated the US-focused segment of the event; Dr. Jiang Jihai, Director of the Juvenile Office of the Research Department of SPC, moderated the China-focused segment.

In his opening remarks, Dr. Jiang spoke about recent changes to China’s juvenile justice laws. He introduced the recently revised “Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Minors,” which focuses on protection across six areas: family, school, social, cyber, government, and judicial. Dr. Jiang then went over “The Law of the People’s Republic of China on Family Education Promotion,” which stipulates that parents are responsible for family education and “bear the corresponding legal responsibility” if they fail or do so incorrectly. Dr. Jiang ended his opening remarks by noting these developments:

In this context, it is timely and significant for us to take the Child Welfare Act as the theme of this forum. We are pleased to brief our American colleagues on the latest developments in the field of juvenile justice in China, and we look forward to learning about your experiences and practices as well…so that we can join hands to contribute wisdom to the further innovation and development of juvenile justice in China and the United States.

Both panels emphasized the importance of cohesive policies that clearly delegate responsibilities at all levels of the judicial system. Chinese panelist presentations focused on guardian revocation, judicial processes for cases of domestic violence involving children, recent developments in child protection legislation, and the need for comprehensive protection including social support systems and joint protective mechanisms. The panelists presenting on China were:

- Chen Haiyi, Standing Member of the Adjudication Committee, Guangzhou Intermediate People’s Court, Guangdong;

- Li Chen, Deputy Director, Division of Supervision of Minors’ Protection, Child Welfare Department, Ministry of Civil Affairs;

- Judge Song Ying, Deputy Chief Judge, Juvenile Division, Beijing High People’s Court;

- Judge Wang Wei, Deputy Chief Judge, First Criminal Division, Jiangsu High People’s Court.

The US panel addressed issues affecting children’s welfare including mandatory reporting, the role of the child protection worker, the right to counsel for both guardians and children in child welfare cases, and the importance of child placement and reunification with parents when feasible. Moderator Judge Edwards has written at length about the value of relative placement for children in foster care. The panelists presenting on the United States were:

- Judge Jerilyn Borack, Presiding Judge, Sacramento County Juvenile Court;

- Judge Roger Chan, San Francisco County Juvenile Court and Chairperson, Juvenile Court Judges of California;

- Judge Marian Gaston, Assistant Presiding Judge, San Diego County Juvenile Court;

- Howard Himes, Consultant and Former Director of Social Services in Napa County, California.

A uniting ethos across both panels was the need for laws and courts to act within the best interests of the child, minimizing harm to the extent possible in every situation and taking severe measures, like child-family separation, only when unavoidable. After the presentation portion of the event, panelists answered questions from the other country’s representatives on specific aspects of juvenile justice. Kamm and Dr. Jiang made closing remarks.

Dui Hua and the SPC began collaborating on expert exchanges in 2008, when Dui Hua expanded its focus to include juvenile justice reform. Since then, exchanges have focused on areas including non-custodial measures, record sealing for juveniles, and girls in the justice system. After expanding its focus again in 2014 to include women in prison, Dui Hua and the SPC, as well as Penal Reform International, collaborated on a program to raise awareness of the Bangkok Rules (English [PDF 1MB], Chinese [PDF 1MB]). Prior to the April 7 exchange, the most recent collaboration occurred in March 2021 when SPC representatives, including Dr. Jiang, participated in the closing webinar of the International Symposium on Girls in Conflict with the Law, speaking about issues facing girl offenders in China.

Kamm’s closing remarks thanked Judge Edwards, who came to Dui Hua with the idea for this webinar in 2021, and “the outstanding team he put together on the US side.” Kamm also thanked Dr. Jiang and “his equally outstanding and accomplished” team. Referencing Dr. Jiang’s opening remarks, Kamm acknowledged his deep friendship with Dr. Jiang.

US-China relations have been defined in recent years by open hostility and adversarial posturing, including talk of decoupling. Legal exchanges, particularly on juvenile justice reform, are a rare area of collaboration. Organizations in the United Kingdom and Germany have done pioneering work in the area of juvenile justice with Chinese counterparts and,on April 8, SPC representatives held a virtual meeting with officials from the European Court of Justice. In the United States, Dui Hua’s engagement with the SPC is in the forefront of exchanges in this crucial area.

“We have done eight programs together, six entirely [together] and two jointly with others. That’s eight programs, and I’m looking forward to cooperating more with you Dr. Jiang and your office in the future,” Kamm said in his closing remarks.

PUBLICATIONS ROUND UP

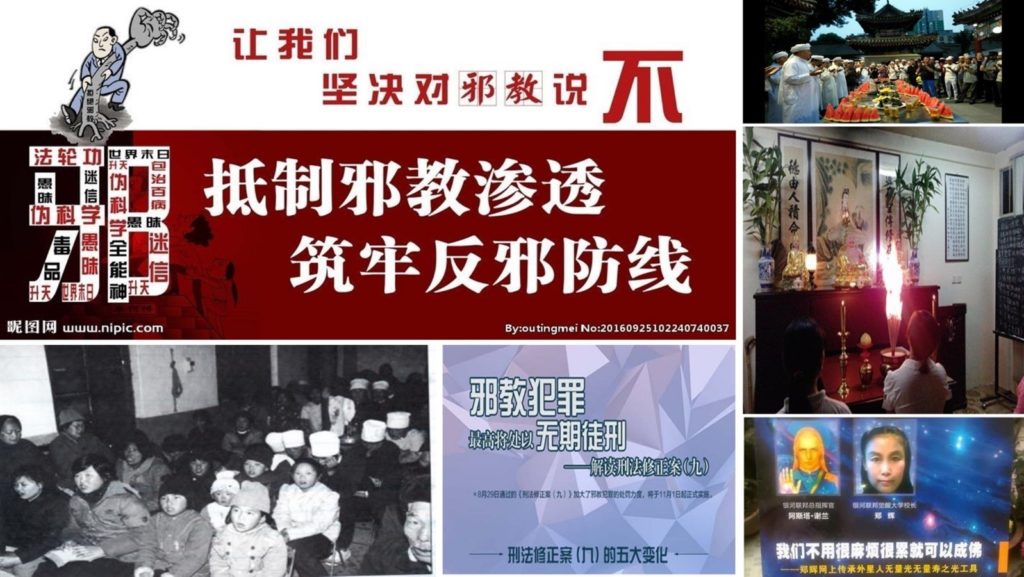

Featured: “The Persecution of Unorthodox Religious Groups in China: A report by Dui Hua,” March 29, 2022

Dui Hua’s new report “The Persecution of Unorthodox Religious Groups in China” [PDF, 1.4 MB] details and analyzes the Chinese government’s treatment of unorthodox religious groups, listing known banned groups and the actions taken against them. The report, compiled over several months in 2021, offers a view into a substantial and largely unrecognized aspect of the Chinese population.

“The Persecution of Unorthodox Religious Groups in China” is based on legal documents, media reports, case studies, official publications, Chinese government responses to requests for information on persecuted prisoners, court statistics, and Dui Hua’s Political Prisoner Database (PPDB). It provides a comprehensive view of how non-state sanctioned religious practitioners come into conflict with the law, how officials at different levels of government criminalize unorthodox worship, and how past trends can inform future advocacy for those undergoing coercive measures for the non-violent expression of their beliefs.

Read more here.

Download the report [PDF 1.4 MB]

Read about the report and other publications about unorthodox religious groups here.

See Also: Human Rights Journal, March 31, 2022: Views of China Remain at Record Low, More See China’s Military as “Critical” Threat

In Gallup’s latest annual World Affairs poll, conducted from February 1-17, the American public’s opinion of China remains at a historic low. The poll, conducted partly during the 2022 Winter Olympics, found that 79 percent of respondents have an unfavorable view of China, with 41 percent answering “very unfavorable.” Only 20 percent of respondents have a “favorable” view of China. The numbers remain largely unchanged from the 2021 poll.

China’s favorability rating is at its lowest since Gallup started to poll American attitudes towards the country in 1979. The Gallup poll also found that Americans view China as a “critical” threat to US security.

Read more here.

JOHN KAMM REMEMBERS

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s human rights advocacy prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999.

Prisoner Lists, Past and Present

Beginning in 1990, I testified on a dozen occasions to Congressional committees in Washington DC. My last testimony was delivered in 2011. On different occasions, I appeared before the House Ways and Means Committee, the House Foreign Affairs Committee, the Senate Finance Committee, and the Congressional Executive Commission on China (CECC), a body whose establishment I had called for in the wake of President Bill Clinton’s decision to unconditionally renew China’s Most Favored Nation trade status in May 1994.

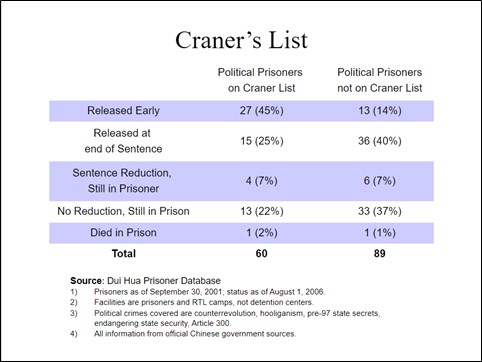

Of special importance was my testimony delivered to the CECC on September 20, 2006. In this testimony I described what had happened to 75 political prisoners whose names were on a list of prisoners handed to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs by Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Rights, and Labor Lorne Craner in the summer of 2001. I concluded that “If you were on the list, you had a better than 50 percent chance of being released or given a sentence reduction in the ensuing five years. That’s three times better than the rate of early release for political prisoners that we know of who were serving sentences in September 2001 but who weren’t on Craner’s list.”

I based my conclusion that being on a prisoner list significantly increased the chance of early release both on my analysis of the Craner list and on interactions with the Chinese government in the 15 years prior to my testimony, including communications with the State Council Information Office (SCIO) from 1991 to 1994. During this period, I asked about and was provided information on more than 70 prisoners, including Democracy Wall prisoner Xu Wenli (徐文立); the information I was given specified the hour and the day he would be released. I was given information on several elderly Catholic priests, as well as many other political prisoners.

Of special significance was a fax received from the SCIO in December 1994. For the first time, I was given written responses to a prisoner list I had submitted earlier that year to the Ministry of Justice. A number of the prisoners on the list received early releases from prison after I had given it to the Ministry of Justice, including:

- Ge Hu (葛湖): A teacher in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, was 35 years old at the time of his arrest in 1989. He was sentenced to seven years in prison in November 1989 for committing counterrevolutionary offences during the 1989 pro-democracy protests. He developed multiple health issues, but the prison refused to grant him medical parole. Seven days after I requested information on him from the MOJ, he was granted medical release. He returned home to be with his wife and young child.

- Hao Fuyuan (郝付元): A farmer from Shandong Province, a hotbed of counterrevolution, Hao was active in the 1989 protests. He circulated a tape condemning Deng Xiaoping and pushed students to boycott classes and listen to Voice of America. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison. I asked the MOJ about Hao, after which he was granted early release, probably in 1996.

- Zhang Chengjian (张成俭): Another farmer from Shandong Province, Zhang claimed to be Mao Zedong’s son. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 1984 for committing counterrevolutionary offenses. The sentence was extended by seven years in 1988 for killing a fellow inmate. I had put his name on the same list as Ge Hu, handed to the Ministry of Justice on October 31, 1994. In 1995, his sentence was reduced, followed by two more sentence reductions in 1998 and 2001, respectively. Dui Hua learned of his release in December 2001.

Although early releases of political and religious prisoners on Dui Hua lists have become fewer in recent years, especially after the Covid pandemic when prisons adopted the unofficial “entry only, no exit” policy, notable acts of clemency still in take place. Among the most noteworthy is the early release of Liang Jiantian (梁鉴添), a printer of Falun Gong literature, announced by Dui Hua in March 2022.

I began asking about him shortly after he was sentenced to life in prison in 2000, not long after Falun Gong was banned. I put his name on 20 lists submitted to the Guangdong Government. In 2007 his life sentence was commuted to 20 years in prison. Multiple sentence reductions were granted until the final six-month reduction in October 2021.

Despite strong evidence to the contrary, policy makers in Washington generally dismiss the importance of submitting prisoner lists to the Chinese government. A principal venue for submitting lists and discussing cases used to be the bilateral human rights dialogue. This was suspended by the Obama administration in late 2016 and has not been resumed, even though Beijing has signaled a willingness to hold another session.

Subscribe here to receive Dui Hua publications by email.