In 2007, Kamm journeyed to China’s Hubei province with a colleague to see how different judicial bodies interacted at the provincial level. Despite a promising start, the itinerary didn’t go as planned, perhaps an early indicator of a fraying relationship between Dui Hua and China’s Ministry of Justice.

<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

In 2007, I toured Hubei Province with a colleague. The visit did not go well and was an early indicator of a fraying relationship between Dui Hua and China’s Ministry of Justice (MOJ). It represented a low point in my dialogue on human rights with the Chinese government.

Earlier on in the year, I had began discussions with a senior official who worked for the Supreme People’s Procuratorate. I had met him in Europe, and then, later, on a visit to the United States.

For a long time, I had wanted to visit a Chinese province other than Guangdong to look at how different judicial bodies interacted at the provincial level. We settled on Hubei in central China. The official with whom I was holding discussions had good connections there.

My idea was to visit a prison, a detention center, and a court, where we could attend a trial. Prisons are under the provincial prison bureau which in turn reports to the prison administration bureau of the Ministry of Justice. Detention centers report to the provincial public security bureau under the Public Security Ministry, while intermediate people’s courts are under the provincial high court. We also wanted to meet with officials to ask about political prisoners and interact with students and professors at a law school. I was especially interested in getting information about Qin Yongmin (秦永敏), one of the founders of the Democracy Party of China. Qin was released at the end of his sentence in 2010. There is no record of his being granted clemency. He was put back in prison to serve a 13-year sentence for subversion in 2015. He is currently serving his fourth sentence in Guanghua Prison in Hubei. Qin’s wife, Zhao Suli, is reported missing. Dui Hua’s advocacy on behalf of Qin Yongmin has continued. To date, the foundation has placed his name on 22 lists submitted to the Chinese government. We have received 25 responses.

I suggested that Joshua Rosenzweig, my colleague at Dui Hua, and I make presentations on, respectively, application of the death penalty in the United States, with a focus on lethal injection, and citizen oversight of police forces in the San Francisco Bay Area. My suggestion was accepted.

The official assured me that my requests would be met, so we moved to the next stage: logistics – dates, transportation, and lodging.

Wuhan University School of Law

Josh and I departed Hong Kong at 8:30 AM on November 14, 2007, aboard a Dragon Air flight, arriving in Wuhan two hours later. It was a cool and misty day. After landing, we went by car to Wuhan University School of Law. There we were met by Dean Ma Kechang. Dean Ma was known for his work as a defense counsel in the trial of the Gang of Four, the group of radicals blamed for many of the excesses of the Cultural Revolution. Ma had represented followers of the disgraced leftist premier Lin Biao, who had reportedly died in a plane crash as he was attempting to flee to the Soviet Union.

Josh made his presentation on lethal injection, in flawless Chinese. It was well received and prompted many questions. I spoke, in English, on Dui Hua’s work on behalf of Chinese political and religious prisoners. Despite the sensitivity of the topic, my remarks were also well received by an enthusiastic audience of students and professors.

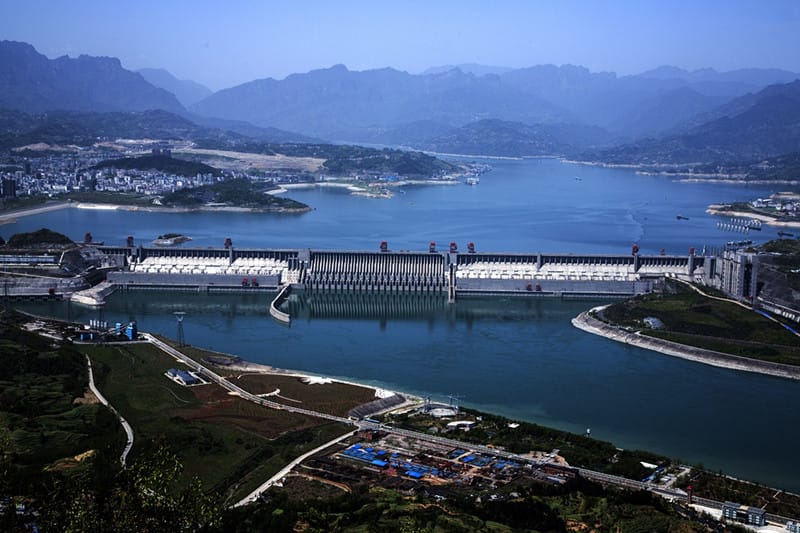

After our presentations at the law school, Josh and I left by car for the four-hour drive to Yichang, a city of more than three million residents most famous for its proximity to the Three Gorges Dam. Upon arrival, we were taken to a banquet room in the hotel at which we would make our presentations the next day. During dinner, I remarked how much Josh and I were looking forward to our visits to a prison and a detention center. Our hosts started to fidget in their seats and stare off into space.

After dinner, the officials came to my room. There they told Josh and me that there would not be a visit to the Yichang Prison. Nor would there be a visit to a detention center. We could not attend a trial. I registered my disappointment. I told them that I would have to consider returning to Wuhan and flying back to Hong Kong. They asked me not to do so. Eventually, I relented, and the show went on as planned.

Citizen Oversight of Police Forces

The next day, November 15, 2007, I began what was to be a three-hour presentation on citizen oversight of police forces. This being a seldom-explored topic in China, where civilian oversight of the police (not to mention state security agents) does not exist, there was considerable interest in my remarks. We were told that this was the first-ever presentation to Chinese officials on the subject.

The presentation took place in the main hall of the Bailong Hotel, site of the Yichang Procuratorate Training Center. The audience consisted of more than 100 officials from the procuratorate and public security bureaus, as well as other judicial bodies in Yichang. It was taped for rebroadcast on closed-circuit television to procuratorates throughout the province. The interpretation was not the best, so Josh jumped in to help. I fielded questions from the audience, after which we went to lunch in the hotel.

Our hosts made one more effort to visit Yichang Prison. The effort failed, and they were reproached for defying instructions. We decided to leave Yichang right away, and we returned to Wuhan. That night we were hosted at a banquet by the Hanjiang Municipal Procuratorate.

A Waste of Time with the “No” Official

We began November 16 with a meeting with officials of the Hubei Procuratorate and the Hubei Prison Bureau. It was a frustrating waste of time. The prison bureau official showed up in his uniform bedecked with ribbons and medals. He arrogantly refused to answer the most basic questions, including how many prisons the bureau administered in Hubei. We pointed out that this information was freely available on-line, and we showed him the Wikipedia entry. He refused to answer questions on prisoners, and he refused to accept a prisoner list from us.

We then went to a detention center, run by the procuratorate, for detained corrupt officials. It was fitted out with video equipment to record the interrogation. Video recording was a new tool integrated to combat coerced confession during interrogation, something our hosts clearly wanted to show off. On the wall was a clock with markings for 24 hours, the time given to the procuratorate to question suspects before handing them over to the police or party inspection committee. Suspects were strapped to a solid wooden chair where they would sit for 24 hours without a break.

Although we were not able to attend a trial, we were invited to meet with judges of the Jiangnan Intermediate People’s Court. We held an interesting discussion on access to court documents and access to trials by foreign observers.

The Hankou Foreign Concession

Saturday, November 17, was given over to sightseeing. We walked around the Old Hankou Concession District. At one point, Hankou was the sight of five foreign concessions: British, French, German, Russian, and Japanese. We sat for a while on an embankment of the Yangzi River. I was reminded by an accompanying official that, in July 1966, Chairman Mao swam the Yangzi near this spot, a seminal incident in the early days of the Cultural Revolution. After our tour, we passed by a souvenir shop and a bookstore. There, I purchased RMB 150 worth of books.

Finally, we visited a Buddhist temple after which we returned to the hotel for an early turn-in. Our flight to Hong Kong, KA851, would leave early on November 18.

Wu Aiying, Enemy of Dialogue

I eventually found out why our visit to Yichang Prison was scrapped. Wu Aiying became Minister of Justice in 2005, and she set about dismantling what had been a good working relationship between the Ministry of Justice and Dui Hua. Wu was widely seen as an ignoramus who knew nothing about the law or policy. She preferred talking about cooking. On foreign trips she accepted expensive gifts, which eventually contributed to her downfall. What finally did her in was her promotion of a conman to a senior position in the ministry. Both this fellow and Wu were expelled from the Communist Party, and the conman was tried. It is not known what happened to Wu Aiying, but many judicial officials fervently hoped she would receive her just desserts – a term of imprisonment in a women’s prison.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.