<< Read all John Kamm Remembers stories

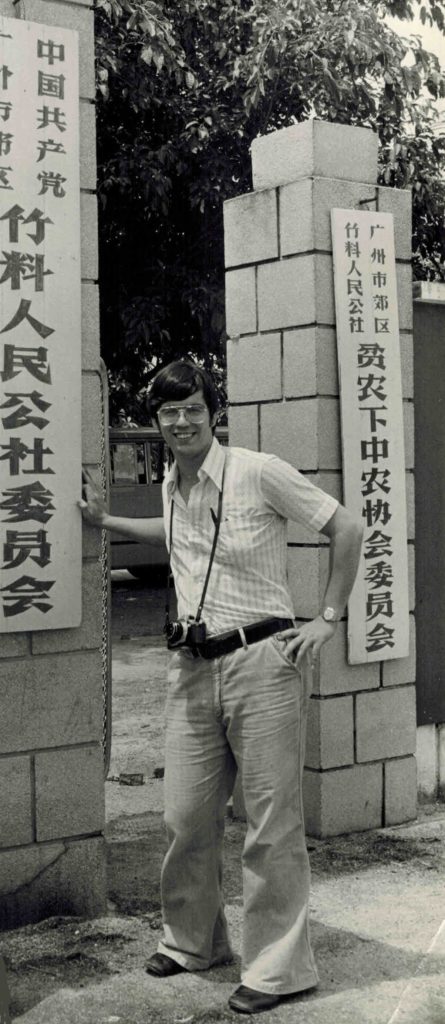

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, before I began intervening on behalf of political prisoners in the wake of Tiananmen, I was active in the China trade, buying, selling, and investing on the mainland. I was in the right place at the right time, taking advantage of China’s opening by launching a number of pioneering initiatives, including establishing some of the first foreign offices in the country, making the first sales to county-level corporations, helping Chinese enterprises register products with the Food and Drug Administration, and placing the first advertisements in Chinese newspapers since the 1950s.

Foreign Offices

On June 5, 1979, I joined a National Council for US-China Trade delegation to Beijing. There I met paramount leader Deng Xiaoping and shook his hand. I was introduced to him as Kang Yuan, a name I adopted upon writing a eulogy for Zhou Enlai, whose funeral I attended in January 1976.

Building on the experience of running the National Council for US-China Trade office at the Guangzhou Trade Fair, I established the first office of a foreign company in Guangzhou in 1979 and the second office of a foreign firm in Shanghai in 1980. These two offices reported to my office in Hong Kong, serving as advance posts for activities throughout the mainland.

The offices were used to plan and carry out technical exchanges to introduce agricultural and industrial chemicals manufactured by the companies we represented and to explore opportunities to buy and sell raw materials and finished products.

My team and I were helping our principal client to find sources of arsenic trioxide, a deadly powder used to manufacture weed killers. We ventured to two remote locations in Guangdong Province, Yunfu County in the western part of the province, and Yangshan County in the northern part. In these places we witnessed arsenic being refined in so-called “dragon kilns,” a technology developed in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD.)

On the trip to Yunfu, I travelled with Mr. Mulligan, a mining engineer who worked for a large New York bank. Accompanied by county officials, we hiked up a steep mountain until we reached a ridge, where we could peer down at the countryside below, dotted with abandoned mines where arsenic-laden rocks had been mined, tailings leaching out from the mouths of the mine.

We stopped for a cup of tea. The county boss remarked that the tea plants were the only thing that could grow in the arsenic-laden soil. We spit out the tea, but Mulligan asked for a bag of what we called “arsenic tea,” which he was given. Turning to me, he said, in a low voice, “I’ll bring this home and give it to my mother-in-law!”

Selling Vaccines to Pigeon Farms

One of the companies we represented was a European manufacturer of vaccines for animals, especially poultry whose flocks were frequently ravaged by disease. We ventured to Zhongshan County north of Macau, there to conduct a technical exchange on vaccines for pigeons. Zhongshan is famous for its “Shekki Pigeons,” named after Zhongshan County’s seat. These birds, roasted in a time-honored way that resulted in succulent meat and crispy skin, fetched high prices in Hong Kong.

On the same trip we introduced a Swiss product to counter swine flu, a perennial problem in South China.

The pigeon exchange was a complete success. County officials, who had their own stash of US dollars, wanted to buy the vaccines from us, but wanted to do so quickly rather than going through the provincial foreign trade corporation.

We decided to use their standard Chinese-language contract used to buy things from mainland companies. Things moved quickly. We signed the contract, the county corporation opened the letter of credit for US$ 30,000, and we arranged the shipment in refrigerated containers. This transaction is believed to be the first sale to a county foreign trade company (known as “sub-branches”) during the reform and opening period.

Low-Acid Canned Foodstuffs

China manufactures a wide variety of canned foodstuffs, including mushrooms and beans, that can be found in stores in Chinatowns around the United States. In 1977 I was asked, as the National Council’s Hong Kong representative, to assist China’s National Cereals, Oils, and Foodstuffs Corporation’s Hong Kong agent register its low-acid canned goods with the United States Food and Drug Administration.

The paperwork was prepared and submitted. All went smoothly, and dozens of products were registered.

The contacts made in this exercise were to serve me in good stead when, in 1978, I was asked by China’s largest firm in Hong Kong, China Resources, to introduce American companies based in the colony who might be interested in investing in the areas bordering Hong Kong and Macau, areas that were slated to become China’s first special economic zones. Investing took the form of “compensation trade” and rudimentary value adding, but they paved the way for joint ventures which began to proliferate in 1979.

Advertisements for Foreign Products

In April 1979, immediately before the Spring Guangzhou Fair which was to open on April 15, I was alerted to an opportunity by a friend who worked for Ta Kung Pao (TKP), a leftist newspaper in Hong Kong. The Chinese government had decided to allow foreign companies, on an “experimental basis,” to place advertisements in Chinese newspapers. One of the newspapers selected to accept advertisements was the Guangzhou Daily (Guangzhou Ryh Bao).

We settled on a price: US$5,000 for a full page, in color, ad. An advertisement for the products of Diamond Shamrock Corporation was laid out and submitted to TKP. It ran in the Guangzhou paper on April 14, 1979.

The appearance of this advertisement caused an immediate sensation. Vendors would fold the paper so that the advertisement, which ran on the back page, showed up as the front page. The novelty added to robust sales for the newspaper which was well known for boring official reporting.

Operating at the Local Level

There is a popular saying in China used to denote Beijing’s limited power to determine what goes on in the provinces and localities: “The mountains are high, the emperor is far away.”

My experiences doing business, particularly in Guangdong Province, prepared me for my human rights work. While the outcome of major political cases is determined at the highest level in Beijing, most cases are handled by local government and party officials including prison bureaus and prison wardens, local courts and local procuratorates. Today, most of the information on political prisoners that Dui Hua obtains is provided by local entities, bypassing Beijing.

Listen to the Encounters with China podcast.

Subscribe to receive notifications about new episodes.

Read all John Kamm Remembers stories.