EVENTS

Dui Hua Helps Secure Freedom for Two Michaels, Lifting of Exit Bans for Cynthia and Victor Liu

On September 25, 2021, Ms. Meng Wanzhou, Chief Financial Officer of Huawei, China’s largest technology company with 180,000 employees, left Vancouver, Canada, after Meng and her lawyers reached an agreement with the United States Department of Justice to defer prosecution, which led to the dropping of the DOJ’s extradition petition. Meng had not been allowed to leave Vancouver since she was detained at the airport in December 2018. She spent the time shuttling between her two mansions, shopping, and sharing meals with her friends.

The same day, two Canadian citizens, former diplomat Michael Kovrig and businessman Michael Spavor, both of whom had been convicted of espionage, were granted medical parole and allowed to return to Canada. They had been detained in China in December 2018. They underwent harsh interrogations under tough conditions. They had suddenly been granted medical parole, an act of clemency that does not require court review.

The next day, September 26, 2021, two US citizens, Cynthia and Victor Liu who had been banned from leaving China since June 2018, had their exit bans lifted. They boarded a plane in Shanghai for their return to New York. Their mother, Sandra Han, remained in a Guangzhou detention center. Chinese police suspected Ms. Han and the two Liu children of involvement with Liu Changming, one of China’s most corrupt officials who fled China having pilfered $1.4 billion from a large Chinese bank. Despite Liu Changming having abandoned the family without telling them where he was going, Sandra Han and the two children endured more than three years of interrogation before the children were allowed to leave. They never spent a day in jail, but they endured intense psychological pressure.

While Dui Hua’s executive director John Kamm played a small role in the negotiations leading to Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor’s release, his involvement in the negotiations leading to the lifting of the exit bans was more consequential.

The Two Michaels

At Kamm’s first meeting with a Chinese interlocutor to discuss the Kovrig and Spavor cases, held in early 2019, he was forcefully rebuffed and told to mind his own business. This case has nothing to do with the United States, Kamm was told by the Chinese diplomat.

At the next meeting with the diplomat, held at the Chinese consulate in San Francisco in the summer of 2019, there was a slight change in tone. “The Meng Wanzhou case and the case of the two Canadians are completely different. They are not related,” Kamm was told.

In late 2019, the same diplomat told Dua Hua’s executive director that “Although the cases are not related, if Meng Wanzhou is allowed to leave Canada, perhaps senior leaders will consider releasing the two Canadians.”

At his first in-person meeting with the consul since the pandemic began in early 2020, held in June 2021, the former businessman was told in no uncertain terms that if Meng Wanzhou were released, Kovrig and Spavor would be released. This followed the meeting between US and Chinese senior diplomats in Anchorage in March 2021. At this meeting Chinese diplomats were told that, as far as the United States was concerned, the two Canadians were as important as imprisoned Americans.

The Liu Family

Kamm became involved in the cases of Sandra Han and Cynthia and Victor Liu in July 2018, one month after Ms. Han was detained and the two Liu siblings had an exit ban slapped on them. Kamm became involved at the request of the family’s New York-based lawyer who had met with a senior administration official at the White House who knew of Dui Hua’s work on behalf of people subjected to coercive measures in China.

Kamm stayed involved in the case until its resolution on September 26, 2021. In the opinion of the New York lawyer who brought him into the case, Kamm was instrumental in bringing the case to a successful conclusion.

During the three-year period of Dui Hua’s involvement in the Liu family case, the foundation submitted 20 written appeals for the siblings and 16 written appeals for their mother. Appeals were submitted to Chinese officials in the United States and China.

Kamm also introduced the New York lawyer to a Beijing-based lawyer with whom Kamm had worked on political cases, including an exit ban case that bore striking resemblance to the case of the Liu siblings. He proved invaluable to the ultimate resolution of the case.

Red Notice

A breakthrough occurred in early August, 2021 as Kamm was preparing for two separate sessions with key Chinese interlocutors. Part of the preparation involved reviewing all media accounts of Liu Changming’s crime and flight from China. Several accounts referred to a “Red Notice” having been issued by Interpol for Liu. Kamm went to Interpol’s searchable website that lists all Red Notices and entered all conceivable spellings of Liu’s name. Kamm concluded that no Red Notice had been issued. He used this to confront interlocutors. “You’ve interrogated these young Americans for three years but haven’t even secured a Red Notice for their father!”

On August 15, 2021, Kamm received an email from his interlocutor at China’s San Francisco consulate. “I’d like to share with you that, during Ambassador Qin’s recent meeting with DDS Sherman, Ms. Sherman expressed her concern for the case of the Liu family. Ambassador Qin had a relatively positive response to her. The Chinese Embassy will report to Beijing again on the importance of the case.” The email was sent nine days after Kamm’s message to the official regarding the Red Notice. According to an informed source in China, the decision to lift the exit ban was made not long afterwards.

On September 26, Kamm received news from a source in China that the Liu siblings were on their way to New York. They arrived the same day, 39 months after they first learned that an exit ban had been placed on them. Their ordeal was finally over.

DUI HUA IN THE NEWS

From time to time, Dui Hua’s work and insights are featured in the press. Developments in high-profile cases have led media outlets to seek out Executive Director John Kamm’s expertise over the last few months.

In August, Kamm spoke to CBC Radio’s As It Happens about the case of still-detained Canadian national Robert Schellenberg and the hostage diplomacy that turned out to be at the heart of the Meng Wanzhou and “Two Michaels” cases. Kamm was interviewed by publications including The New York Times, CBC Radio’s Power & Politics, The Washington Post, China Digital Times, Toronto Star, and The Montreal Times in August after the trial and sentencing of Michael Spavor. Following the releases of Michaels Spavor and Kovrig after Meng Wanzhou, Kamm spoke with Politico, The Wall Street Journal, the CBC, Global News, and The New York Times.

Since August, Kamm has given 10 interviews for different media outlets, and Dui Hua has appeared in 25 original articles, which have been syndicated in 51 publications in regions including China, Vietnam, France, Taiwan, and Switzerland and in languages including Mandarin, French, Vietnamese, Khmer, and Spanish.

EXCHANGES

Exchanges is a feature that explores Dui Hua’s expert exchanges and dialogues.

“Racism is part of the moral panic around girlhood.”

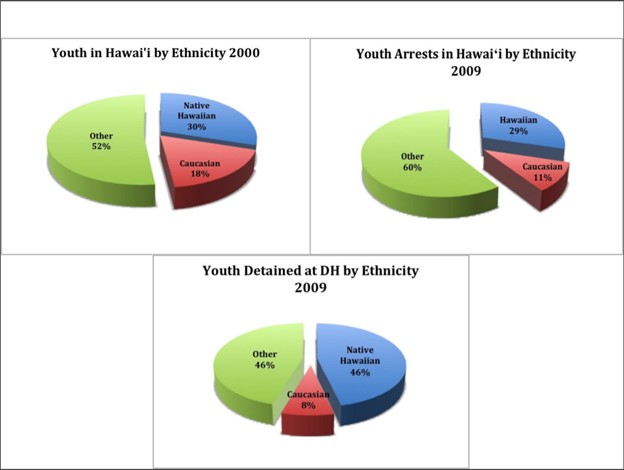

The intersection of discrimination, race, and juvenile justice is a key focus of any discussion about youth criminal justice systems. The International Symposium on Girls in Conflict with the Law (GICL) explored the disproportionate effect family trauma, failed economic systems, and broken justice systems have on youth from Indigenous populations and communities of color.

Activist-artist Richard Ross, who has spent over 15 years photographing incarcerated juveniles in the United States, repeatedly emphasized racial disparities entrenched in the US system: every child sentenced to life without parole in the United States for a non-homicide has been a person of color; Latino youths are four times more likely to receive an adult sentence for the same crime as white youths and African American youths are nine times more likely to receive an adult sentence for the same crime. “The story that you have to tell essentially is, when you can predict that an infant boy of color in a particular zip code is more likely to go to prison than to college, you have to be able to accept that it’s our fault more than his.”

Girls of color make up 62 percent of incarcerated girls in the United States despite being only 22 percent of the youth population. Gena Castro-Rodriguez, Chief of the Victim Services Division, San Francisco District Attorney’s Office said, “We want to think about girls of color that in the United States are overrepresented for African American, Latina, and Native American girls, and how we’re overusing incarceration as a treatment strategy, instead of treating the trauma that these young people have been exposed to and experienced.”

Meda Chesney-Lind of the University of Hawaii at Manoa pointed out that African American girls are also three times more likely than their white peers to be incarcerated. Native and Indigenous girls are more than four times more likely than whites to be incarcerated. “Racism is a part of the moral panic around girlhood, and particularly girls of color are demonized [by media and society].”

Social worker Michelle De Young shared the story of Natasha and her experience filing a report after being sexually assaulted. The child welfare social worker writing Natasha’s report doubted her account because she didn’t cry when relating the details of her assault. “Too often, those of color have their words discounted, especially young women of color. In a criminal justice system, you’re usually working with fractured individuals and fractured institutions. People ask how we can change the criminal justice system. First, we have to acknowledge that this system was created from racial institutions because right now, 99 percent of my clients are young people of color,” De Young said. Judge Susan Breall, who works in the same geographic area as De Young, also noted that young African American woman are arrested at five times the rate of other ethnic groups.

Native American youth are 30 percent more likely than white youth to be referred to juvenile court than to have charges dropped. In Canada, Indigenous people have more interactions with policing services than non-Indigenous, usually with different outcomes. Christa Big Canoe said, “If you take a Caucasian youth who’s from a middle-class or affluent family and you take an Indigenous child and they commit the same offense and they both go through the criminal justice system, you can almost always demonstrate that the Indigenous youth will get more serious punishment than the non-Indigenous youth.” Data from 2018 found that, in Canada, Indigenous youth aged 12 to 17 made up 43 percent of admissions to correctional services despite being about 8 percent of the entire population.

Describing a scene he witnessed during his work in the US juvenile justice system, Ross described an African American child in a courtroom facing two white public prosecutors and thinking ‘How does [that] feel?’ Ross continued, “These are lonely, powerless people. Every one of these children need mental health services. These are kids without a voice from families without resources, from communities without power, and that’s got to change somehow.”

To learn more about the panelists, watch their individual webinars, and read a full list of recommendations visit girlsjustice.org.

PUBLICATIONS ROUND UP

Featured: Human Rights Journal, September 21, 2021: Mainland China Administrative Deacon Station: Leaders Receive Lengthy Sentences

In 2000, the Ministry of Public Security issued a circular concerning the identification and banning of 14 evil cult or sect organizations. Of them, 12 were unorthodox Christian groups. Following hefty prison sentences given to founders in the 1990s, many of these groups have been severely weakened, driven underground, or have gone extinct. After state repression of religion intensified in late 2012, there appears to be a consensus that Almighty God has become the most suppressed Christian sect in China, but the continuing crackdown on other smaller and lesser-known Christian groups which are similarly considered “unorthodox” has not garnered the same level of scrutiny.

Read more here.

See also: Human Rights Journal, October 12, 2021: Article 299: Criminalizing Disrespect of the National Flag, Part I

The desecration of national symbols evokes different responses from different governments. In some countries it is an acceptable form of political expression, in others an act that is merely tolerated, and in others a crime. China is among the countries that place broad restrictions on speech to criminalize acts it finds disrespectful to national symbols.

Drawing on Dui Hua’s research into news media sources, court records, and online judgments, this article sheds light on the little-discussed topic of flag desecration in China. Part I looks at trends in sentencing and the law’s application across different cases. Part II explores how the law is applied to different groups like Falun Gong, Tibetans, and Uyghurs. Most publicly disclosed cases involve “ordinary” offenders who did not make a political point against the CCP. However, the same acts committed by practitioners of Falun Gong and ethnic minorities tend to result in lengthier prison sentences.

Read more here.

JOHN KAMM REMEMBERS

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s human rights advocacy prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999.

Kamm’s List

Last month’s installment, “Memories of 9/11,” recounted August-September 2001, when Kamm was approached by Tina Rosenberg about being the subject of a New York Times Magazine profile, and Kamm’s experience in China in the wake of the September 11 attacks. This article continues that story.

State Security

Tina and the photographer retained by the Times to cover our visit, Zeng Nian, arrived in Beijing from New York in the late afternoon of December 17, 2001. I met them in the lobby of the Jianguo. From the moment of their arrival going forward, we were the objects of attention by state security. One of my drivers later told me that he was summoned for questioning and shown photographs of our arrival at different ministries.

Tina and I had dinner at the Jianguo. We discussed the schedule for the days ahead.

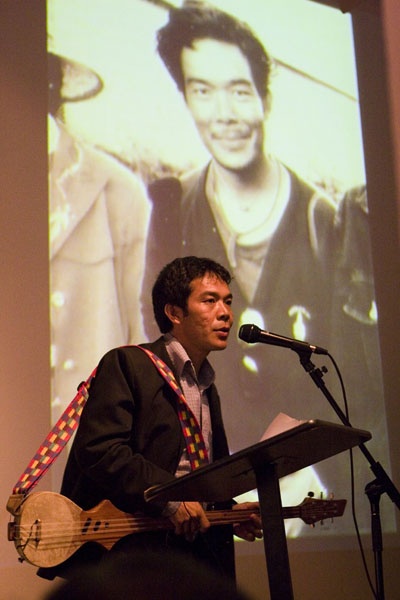

On December 18, Tina, Zeng Nian, and I went to the MFA for a meeting with Li Baodong. The purpose was to discuss the possible release of Ngawang Choepel, a Tibetan musicologist who had studied at Middlebury College in Vermont and had been detained in September 1995 on a trip back to Tibet to film folk dances and record traditional music, and to see his mother. His had become an important case for Senator Jim Jeffords, R-Vermont, a pro-trade politician who had nevertheless voted against China’s Most Favored Nation (MFN) in 2001 over the way Ngawang Choepel and his family were being treated.

While we were introducing ourselves in came Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing, who had recently returned to Beijing from Washington where he had served as ambassador. Li was familiar with the Ngawang Choephel case. Senator Jeffords’ vote against MFN had made an impression. After 9/11 Li Zhaoxing had recommended, to President Jiang Zemin, that political prisoners be released to improve the relationship with the United States, a seemingly contrarian move. Why make concessions to the United States when it was the United States that was seeking support from China?

At the MFA, Foreign Minister Li introduced Tina to Li Baodong. “This is the good Mr. Li,” he quipped. “There’s another Li who lives in Taiwan. He’s the bad Mr. Li.” The foreign minister was referring to President Lee Tenghui, seen by the Chinese government as enemy number one. After the foreign minister left the room, Li Baodong and I discussed the Ngawang Choepel case in cryptic terms. We agreed that we would meet again the next day.

For lunch, Tina and I were hosted by a large group of foreign diplomats assembled by Mark Lambert, the US embassy’s human rights officer, in the best Italian restaurant in Beijing, Aria. They spoke one-by-one about their dealings with China on human rights. In those days, China was engaged in around 10 human rights dialogues with foreign countries. Now there are none.

Tina and I parted ways. I went on a visit to Beijing Number Two Prison. The MOJ had denied a request for Tina to join me. She went back to the MFA for a private interview with Li Baodong. We reconnected for dinner with Mark Lambert.

Not surprisingly. Tina wanted to gauge the opinion of American businesspeople about what I was up to, promoting respect for human rights on the part of the American business community in Beijing. I had set up a breakfast with the American Chamber of Commerce for 7:30 AM on December 19. Those at the table were defensive, citing the good work done for orphans and flood victims. Tina adopted a skeptical air. Outside the room, state security was listening.

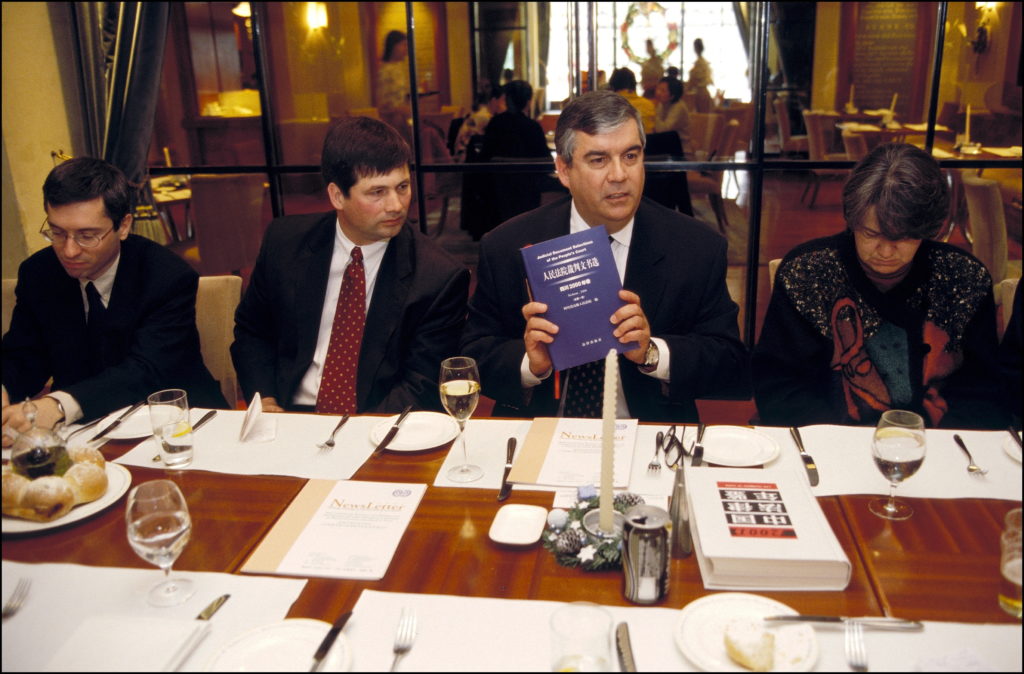

After the breakfast, we went to the Supreme People’s Court for yet another uncomfortable meeting. The head of the Foreign Affairs Bureau, Mr. Liu Hehua, had clearly been caught off guard. I presented a letter from “my cousin,” Senator Orrin Hatch, and pummeled him with questions about the fate of the China Plum Blossom Party and the pamphleteer Yu Rong. I offered to provide assistance to Mr. Liu with materials on the American justice system.

As we were leaving, Mr. Liu took our photographer aside and sharply asked him about what was going on. The photographer was told that that he should be careful about who he worked for. It was not what the photographer, a French citizen with family in China, had anticipated.

There are two bookstores that were selling volumes related to judicial matters, including those related to trials for political offenses, near the Supreme Court. (NB: The bookstores no longer offer such books.) We surveyed their offerings under the watchful eyes of suspicious shopkeepers. I bought a couple, and then we were off for a photoshoot at the old Beijing railway station.

I departed Beijing on the 5:30 PM Dragon Air flight to Hong Kong. After three days doing research and briefing clients I returned to San Francisco on December 23, in time for Christmas.

On January 16, 2002, Tina called me with the news that her editor had decided that the entire article – now a profile – would be devoted to my work. The aim was to publish it on February 16. There followed more calls between Tina and me, one on February 5 devoted entirely to Ngawang Choephel’s release that had taken place on January 20. “Wrap up” interviews followed.

The first of two fact-checking interviews with the Times editorial staff followed. I was asked to estimate how many prisoners I had helped in the years since I began intervening on behalf of Chinese prisoners in May 1990. This entailed going over trip reports and notes. Finally, I estimated that I had helped around 250 political prisoners win early release or better treatment. During the last of these fact-checking interviews, I managed to tease the title of the article, now billed as a cover story for the Times’ Sunday Magazine, out of the fact-checker: “John Kamm’s Third Way.” I concluded that Chinese feathers would not be ruffled by this title. The story was slated to appear on Sunday March 3, 2002.

I left for Hong Kong on February 26, thence to Beijing on March 10. In Hong Kong, I intended having dinner with my Guangdong interlocutors, taping a show for VOA, giving a speech to the Asia Society, and conducting research in Hong Kong libraries. Most important, I wanted to gauge reactions to the cover story, due for publication during my days in Hong Kong.

On Friday, March 1, my cell phone went off while I was in the stacks of the Hong Kong University library. I stepped outside to take the call from my wife. The story had been published on the Times’ website on Thursday, February 28. “I thought you said that the title of the story was ‘John Kamm’s Third Way,”’ she said. “In fact, the title on the cover is ‘Kamm’s List.’” That’s when I learned that there are in fact two titles for a cover story. One for the cover, which is decided by the graphics people, the other inside the body of the article decided by the editorial staff.

The latter was in fact “John Kamm’s Third Way.” The cover was a mockup of a movie poster that closely resembled one of the movie posters for Steven Spielberg’s 1993 hit movie Schindler’s List.

Schindler’s List

I shuddered. It would be hard to avoid the comparison between Kamm, saving Chinese prisoners from the Chinese government, and Schindler, saving Jews from the Nazis. I anticipated a sharp reaction from Chinese officials in Beijing – assuming I was allowed to enter the country.

I need not have worried. I entered China on March 10, 2002, without incident. The next day I met with Li Baodong and La Yifan. La advised me that he was monitoring reactions to the article among Chinese officials and National People’s Congress and political Consultative Congress deputies, assembled in Beijing for their annual meetings, the so-called “Two Sessions.” Thus far there had been no negative reactions. I told them that there was unhappiness with the article among American businessmen. Li Baodong airily waved his hand: “Don’t worry. They’ll get over it.”

A young official escorted me from the ministry to my car. “Imagine,” he said. “An article about human rights in China in which the Chinese government is not the biggest villain!”

On the afternoon of March 11, I went to the MOJ’s headquarters where I was received by two directors: Wang Lixian, head of the International Department, and Liu Fuchen, head of the Prison Administration Bureau. We sat down and director Liu fixed his eyes on me. “Mr. Kamm, wasn’t there an article about you published in the United States recently?” I said yes, there had been a story about me in the New York Times Sunday Magazine published a few days before.

“What was the title of the article,” Liu asked. “John Kamm’s Third Way,” I replied. Liu shot back. “No, that’s not the title I remember.” I explained that “Kamm’s List” was the title on the cover of the magazine. “John Kamm’s Third Way” was the title listed in the table of contents and inside the issue itself. Liu continued his line of questioning. “Wasn’t there a movie with a title similar to that?” I confessed that there was: “Schindler’s List.”

Liu rubbed his hands and exclaimed: “Won an Oscar, didn’t it? Excellent!”

An Unhappy Exchange

After a final meeting with Li Baodong on the morning of March 13, I went to the Supreme People’s Court where I was received by Liu Hehua. He was not happy, taking special umbrage at a line in the story: “Kamm not only speaks Mandarin and Cantonese but also the language of the party which is just as important.” Liu adopted a threatening tone. “This will not end well for you.” It turned out that Liu was relying on a translation of the article and not the actual article itself. I admonished him to read the original, and not rely on a translation.

I returned to Hong Kong on March 14 and flew back to San Francisco on March 17, satisfied that, while members business community were not happy – the head of a large business group that promotes trade with China was especially angry – the Chinese government was, for the most part, satisfied with the article, as was the case with the human rights community.

Today, “John Kamm’s Third Way” is required reading in courses on business and human rights, including those taught at Harvard Law School, Columbia Law School, and Princeton University. A testament to Tina Rosenberg’s writing, it has stood the test of time.