EVENTS

New Challenge for US-China Relations: Summit of the Democracies

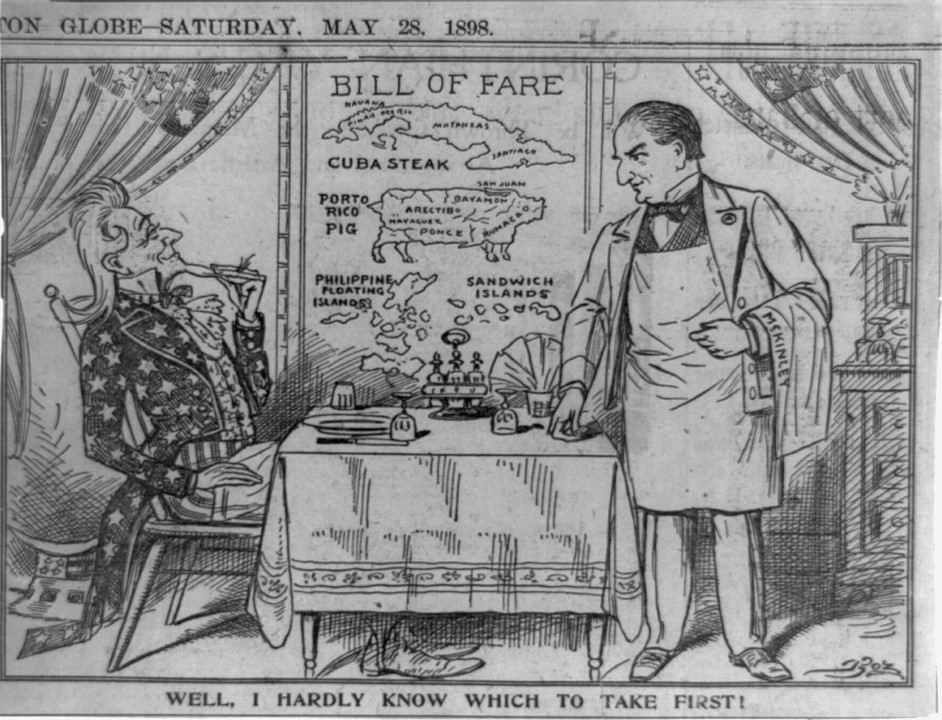

The collapse of Afghanistan following an 11-day offensive by the Taliban has led to a sharp drop in President Joe Biden’s approval ratings and resulted in yet another challenge for US-China relations. Observers in Washington have noted that the offensive began days after a Taliban delegation visited Beijing for a meeting with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi. The Taliban reportedly offered assurances that they would not interfere in China’s internal affairs by supporting their fellow Sunni Muslims, the Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

After the Taliban routed the American-backed government in Kabul, China called for other countries to give the Taliban a chance and not to dismiss the possibility that the group, considered terrorists by the United Nations and many countries, has turned a new leaf. China’s motivations behind its cozying up to the Taliban are thought to involve access to Afghanistan’s large deposits of rare earths, a precious commodity supply of which China already monopolizes, raising concerns over the country’s dominant position in the global supply chain, as well as denying to the Uyghurs a source of support.

Another point of conflict looming on the horizon is the Summit of Democracies, a virtual event scheduled to take place in Washington on December 9-10, 2021. China, considered an authoritarian Communist state, will not be invited to participate. However, Beijing is deeply concerned that Taiwan, which it considers a breakaway province, will be invited to attend and speak.

The possibility that its president, Tsai Ing-wen, will be a keynote speaker on the stage with leaders of G7 democracies, is raising alarm bells in Beijing. Mainland media outlets have gone so far as to suggest that an invitation to Taiwan would constitute an act of war. Hardly noticed however is Beijing’s deep concern that pro-democracy exiles from Hong Kong might also be invited to speak at the summit.

The fall of Afghanistan and the looming Summit of Democracies join a long list of irritants in US-China relations. These include:

- China’s activities in the South China Sea: On her visit to Singapore and Vietnam in late August, US Vice President Kamala Harris rebuked China for intimidation, violating international norms by seizing vital waterways, threatening freedom of navigation, and building artificial islands bristling with weapons. The United States is increasing the frequency of its sail-throughs near contested islands.

- Climate Change: US climate envoy John Kerry traveled to Tianjin in early September for meetings with his Chinese counterpart. He hoped to convince China to do away with reliance on coal. In the end, he came away without any agreement on how the two countries can reduce carbon emissions. During his visit, he had a virtual meeting with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi. Wang made it clear that cooperation on climate change depended on the United States dropping its “hostile” policies towards China.

- Dueling military training: Military exercises with Iran and Russia were countered by US-led joint naval exercises off Guam in late August. These exercises brought together the navies of the United States, Japan, Australia, and India.

- Report on Covid origins: President Biden ordered US intelligence agencies to investigate whether the Covid pandemic, which has killed more than 600,000 Americans, resulted from a leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology. A report was issued in August. It was inconclusive.

- Trade frictions: China’s surplus with the United States continues to climb. Beijing is demanding that the Biden administration lift the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration.

- Audits: China has ordered a leading US firm conducting audits of forced labor allegations to close up shop and leave the country. Meanwhile, the Securities Exchange Commission continues to tighten auditing requirements for Chinese firms listed on American exchanges.

- Lithuania: The United States has offered support to Lithuania in its effort to bolster ties with Taiwan. The Baltic State and China have withdrawn their ambassadors amid signs of increasing pressure from China. Lithuania has emerged as a vocal source of defiance to China’s entreaties in Central and Eastern Europe, withdrawing from its 17+1 summit in 2021 and establishing official diplomatic ties with Taiwan.

Agrément

After a delay of several weeks during which China dispatched its own ambassador to Washington, Beijing finally granted agrément to Nicholas Burns to take up the position of Ambassador to China. Beijing is thought to be unhappy with the choice of Burns as ambassador, preferring someone like a retired senator with better access to President Biden.

Burns must now be confirmed by the Senate, no easy task as Senator Cruz (R-Texas) has put a hold on virtually all ambassadorships. Although votes on nominees by the Senate are being held up, hearings on nominations can take place. What Mr. Burns says at his confirmation hearings will attract attention in Beijing and set the tone for US-China relations for the next several years.

Interactions Few and Far Between

Despite the number and complexity of issues dividing the two countries, senior officials in Beijing and Washington have rarely engaged with each other. When meetings have occurred, they have been tense and unproductive. Defense Secretary Austin has yet to meet his Chinese counterpart.

President Biden has boasted of his personal relationship with Xi Jinping, saying he spent “24-25 hours of private meetings” and traveled 17,000 miles with Xi when Biden was vice president. Nevertheless, the two men have only spoken on two occasions since Biden’s inauguration in January. The latest call, at Biden’s request, took place on September 9 and lasted 90 minutes. It was “respectful,” “familiar,” and “candid,” according to an administration official quoted by CNN. Both leaders listed areas of existing conflict and possible areas of cooperation, but Xi stuck to the position that cooperation was not possible unless the United States stopped criticizing China. It is not known whether the two men will meet at the G20 summit in Italy in October.

EXCHANGES

Exchanges is a feature that explores Dui Hua’s expert exchanges and dialogues.

“…those systems have been abolished in the UK for being outdated, but here they remain.”

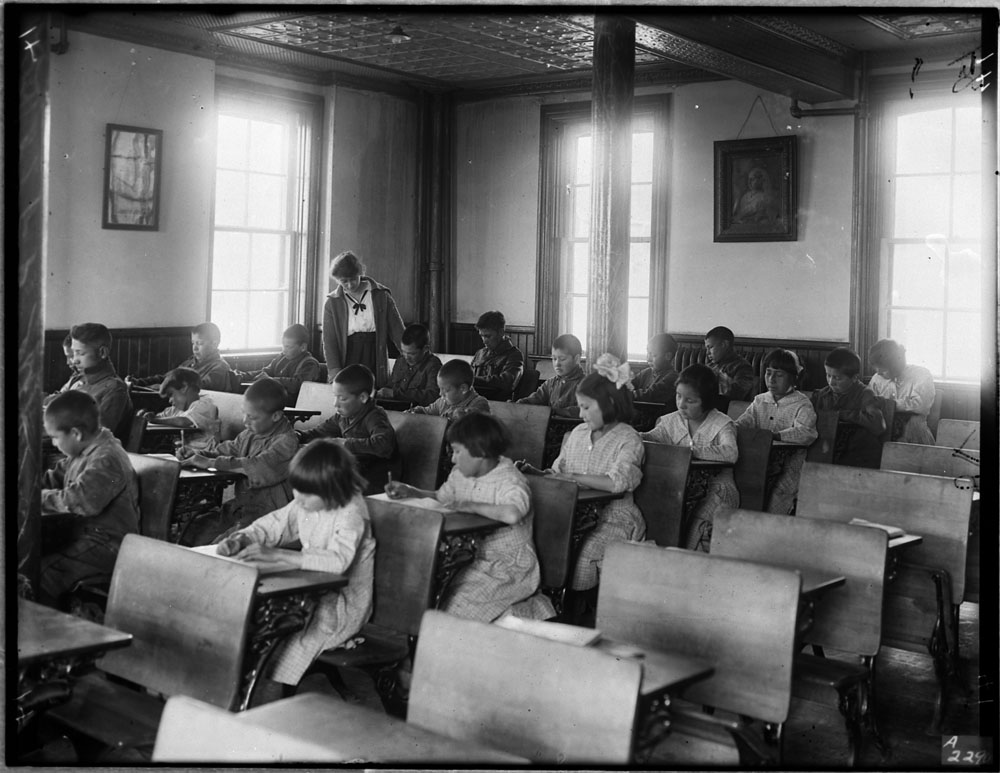

Among the participants of the International Symposium on Girls in Conflict with the Law (GICL) were experts from post-colonial areas. Panelists spoke of how colonial-era laws continue to shape juvenile justice, sometimes in unexpected ways.

As a former British colony, Hong Kong has laws that reflect colonial-era legislation. Instead of being abolished, such laws have been expanded to criminalize more behavior. “We now have charges on the colonial-era laws for remarks regarded as seditious, such as ‘Liberate Hong Kong’ ‘Revolution of our times’, ‘Five demands, not one less’, these are slogans that I have heard chanted by young people over and over again,” said Anna Wu, Honorary Fellow and Professor at the University of Hong Kong.

Legislation like this particularly affects young people, with the youngest arrested protester in Hong Kong being age 11. Wu advocates for the creation of a Children’s Commissioner for this reason. “Minors do not have full capacity to act on their own and can get very lost in the system. Some very young offenders in Hong Kong today are affected by offenses which are rooted in politics, and a dedicated commissioner would provide a voice for children and act as first responders in cases of crises.”

Nafula Wafula of the Commonwealth Youth Council spoke about the lingering aspects of Britain’s presence in Kenya’s juvenile system as well as those of fellow former colonies Uganda and Tanzania: “A lot of those systems have been abolished in the UK for being outdated, but here they remain.” The continued use of Borstal institutions—a detention center for youth—is an example of an outdated colonial structure. The United Kingdom used these institutions from 1908 until 1982, when they were abolished in favor of more modern youth custody centers.

“When I speak about a decolonizing agenda, I think more justice can be done by looking at the various practices that I’ve seen different organizations incorporate in their work,” said Wafula. “For example, organizations within rural settings are moving more and more towards a kind of mentorship approach or rather tapping into systems that exist already that focus on mentorship and support for girls, or for children, as opposed to criminalization.”

Prior to colonization, over 615 first nation Indigenous people across the Canadian region had their own laws. Colonial-based legislation has been used to forcibly relocate people into remote areas. This is the foundation Christa Big Canoe of the Aboriginal Legal Services of Toronto emphasizes when talking about the treatment of Indigenous girls within Canadian institutions.

“People will say we’re in a post-colonial era and I’ll respectfully disagree with that. We still in Canada have something called the Indian Act. So, we’re the only free and democratic country in the entire world that actually has a race-based act that legislates different laws and rules for first nation or “status Indians” in the country.”

The Indian Act—passed in 1845—authorizes the government to remove children from their families. Neglect is usually cited to justify removal, but this neglect is often the result of forced relocation to areas lacking economic opportunities. Big Canoe said, “When children are removed from their homes, their community, when they lose their language, when they lose their culture, they have an increased chance of experiencing interactions with the criminal justice system.”

Similar effects have been seen with Indigenous youth in Hawaii. Meda Chesney-Lind of the University of Hawaii at Manoa described how native Hawaiian youth continue to be relocated for punitive measures: “There are girls that they said needed mental health work and help, and that involved sending them to mainland facilities. Now, these are native Hawaiian youth, very much tied to the land and their culture, and they’re being sent to places like Utah.”

As former colonial powers continue to distance themselves from the practices of the previous century, vestigial policies continue to isolate youth when they are most impressionable and vulnerable. Rather than acknowledging the need for more infrastructure and community engagement, legal systems continue to pursue solutions based in the culture of assimilation.

To learn more about the panelists, watch their individual webinars and read a full list of recommendations visit girlsjustice.org.

PUBLICATIONS ROUND UP

Featured: Annual Report 2020, September 13, 2021

Dui Hua is pleased to announce the release of its 2020 Annual Report. In a year marked by intense challenges and deteriorating US-China relations, Dui Hua was one of the only organizations to continue a dialogue on human rights with the Chinese government. Our achievements in advocacy for political and religious prisoners in China amongst the shrinking of civil society and the erosion of basic freedoms are reminders that dialogue is more important than ever.

Read about our work in the 2020 Annual Report here.

See also: Human Rights Journal: Chinese Asylum Seekers in Bangkok, Part I (August 11, 2021) and Part II (August 25, 2021)

China has consistently ranked among the top 20 refugee producing countries every year since 2003, according to statistics published by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). The latest statistics published in June 2021 indicated that China was 18th on the UNHCR’s list at the end of 2020. The number of UNHCR-registered refugees originally from China reached 175,585. Additionally, there were 107,864 Chinese asylum seekers around the globe with pending claims. The number of asylum seekers increased nine-fold from just 11,375 in 2011, the year before paramount leader Xi Jinping assumed power.

JOHN KAMM REMEMBERS

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s human rights advocacy prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999.

Memories of 9/11, Part I

In the late summer of that year my family and I lived in an apartment in San Francisco that overlooked Chinatown below, and then, down to the Bay and Alcatraz Island in the distance, enveloped in gray fog.

On August 21, 2001, I was sitting at my desk when the phone rang. The caller identified herself as New York Times journalist Tina Rosenberg. I was not familiar with her name.

Ms. Rosenberg told me that she was working on an article that might appear in the paper’s Sunday Magazine. The article would examine the nexus between business and human rights in countries where foreign multinational corporations were conducting business. She mentioned Royal Dutch Shell’s operations in Nigeria and Adidas’ sneaker-manufacturing in Pakistan as possible subjects worth exploring. For China, she wanted to focus on my work on behalf of political prisoners.

We agreed to talk again the next day. As soon as the call ended, I did an Internet search for Tina Rosenberg. I was impressed by what I found. Tina Rosenberg was, and is today, one of The New York Times’ most accomplished journalists. She was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, dubbed the “Genius Award,” in 1987, when she was 27 years old. This was followed by a National Book Award in 1995 and a Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction in 1996. All of this was accomplished before she reached the age of 40. I decided to work with her on the article. I informed her of my decision the next day.

When we spoke on August 22, 2001, I advised Tina that I would travel to Hong Kong and Beijing in September. We spoke again on September 7. I left for Hong Kong the next day, arriving on September 9. I checked into the Marriott Hotel in Pacific Place, an old haunt.

In those days, I had my own show on the Voice of America, and I had lined up several shows to be recorded on this trip. The first show – a program on prospects for political reform in China – was recorded on September 10 at the studio in Wanchai.

The 9/11 Attacks

The next day, September 11, 2001, I made last-minute arrangements for the trip to Beijing, confirming appointments with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), and the Supreme People’s Court. The highlight of the trip was to be a dinner hosted for the MOJ to celebrate 10 years of our cooperation. I had secured letters of congratulations from four members of Congress to present at the dinner.

September 11 was capped off with a dinner, in the hotel’s Chinese restaurant, with two of my interlocutors from Guangdong Province. They provided information on seven political prisoners in the province, including the last prisoner connected to June 4, 1989, protests imprisoned in Guangdong. I returned to my room around 9 PM to begin packing for my flight to Beijing the next day.

Upon returning to my room, I found the message light flashing. It was a brief message from my VOA producer in Washington. “Turn on your TV,” it said. “A plane has just crashed into the World Trade Center (WTC) in New York.” I turned on my TV to CNN and saw smoke billowing from the WTC’s North Tower. I watched another plane crashed into the South Tower at just after 9 PM. I continued watching until both towers collapsed one after the other, in pancake fashion, at 10:20 PM.

I didn’t know it at the time, but a close family member had been killed at the very beginning of the attack, the victim of a head-on collision by the jet that crashed into the North Tower. Many of his colleagues at Cantor Fitzgerald were killed in the attack.

After 9/11, air traffic between the United States, Europe, and Asia was suspended, but planes continued to fly between destinations outside the United States. I went out to the airport early for my 11:35 AM Dragon Air flight to Beijing. I needn’t have done so. The departure hall was empty. The cancellation of flights to and from North America had had a devastating knock-on effect on air traffic around the world.

Arriving at Beijing Airport in the early afternoon, I was picked up by my driver and taken to the Jianguo Hotel. After checking in, I called the US Embassy. The new ambassador, Clark “Sandy” Randt had recently arrived. Sandy was an old friend from our days together in Hong Kong. A personal friend of President George W. Bush, Sandy would go on to become the longest serving American ambassador to China.

Sandy Randt had lost a close friend in the 9/11 attacks, and I had lost a cousin. After commiserating, I invited him to the dinner for the Ministry of Justice, to be held on the evening of September 13. He accepted. Sandy also agreed to do a VOA interview with me right before the dinner.

On the morning of September 13, 2001, I met with the Supreme People’s Court to discuss the case of Yu Rong, a Shanghai worker who had been arrested in 1990 in the largest counterrevolutionary pamphlet case in the history of the city. Yu had scattered 1,400 leaflets from the tops of Shanghai buildings. He was subsequently placed in a psychiatric detention center. After this meeting I had lunch with Mark Lambert, the human rights officer at the United States Embassy. This was followed by the VOA interview with Ambassador Randt at the embassy.

The dinner itself, attended by senior officials at the MOJ, the China Society of Prisons, and the MFA, was a somber affair. Not a good occasion for feasting and drinking. It broke up early.

The next morning, I was driven to the MOJ’s headquarters for a 9:00 AM meeting with Wang Lixian, director of the International Department, and his colleague Zhang Qing. I was told that I would not be given any information on prisoners on this visit to Beijing. I registered my disappointment. “At this time when my country is grieving, I come to Beijing to see you and to receive responses to my inquiries. And what do I get? Nothing.” My bitterness and disappointment showed. I choked up and couldn’t continue.

I summoned my driver and returned to my hotel. After eating my lunch, alone, I went to see Director General Li Baodong of the MFA’s Department of International Organizations and Conferences as well as his colleague La Yifan, effectively Li’s number two, and Li Xiaomei. At this meeting I broached the idea of having Tina Rosenberg come to Beijing as part of a story for the Times on my work. I also complained about how I had been treated by the MOJ.

I stayed behind in Beijing one more day to attend the Memorial Mass for the victims of the 9/11 attacks held at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception on Saturday evening, September 15. A priest, a member of the Patriotic Church, kept local Catholics from attending the service. I returned to Hong Kong the next day, checking into the Marriott.

On September 17, 2001, I received an unexpected call in my room at the Marriott. Director Wang Lixian was in the lobby and wanted to meet me. I went downstairs for a short meeting. Wang advised me that they were gathering information in response to some of my requests. They intended to fax it to me over the coming days. I advised him that I would be returning to San Francisco on September 27 and requested that he fax the information to me there. He agreed. We shook hands and he left.

Over the next nine days I kept a full schedule in Hong Kong. I met with foreign diplomats, including the papal nuncio and the American consul general, Dui Hua donors, business leaders, and family and friends. I carried out research at university libraries, finding the names of hundreds of previously unknown political prisoners. I taped a VOA show on the Hong Kong economy.

I flew back to San Francisco on September 27 and, upon returning home, found the promised responses on prisoners from the Ministry of Justice on my fax machine. It was an extraordinary document: information was given on nine prisoners including high priority Tibetan prisoners Jigme Sangpo and Ngawang Sangdrol. A number of early releases had taken place. More would come, including both Tibetans.

Washington

On October 14, 2001, I flew to Washington DC, a tense city still in shock from the attack on the Pentagon on September 11. Security was tight. Troops were everywhere.

I met Tina for dinner at McCormick & Schmick’s on K Street on October 15. It was our first face-to-face meeting. We reviewed progress to date, and I briefed her on recent developments with respect to cases, including those of Liu Baiqiang, a Guangdong prisoner who tied political messages to the legs of locusts and released them from his cell – I dubbed him the “Locust Man” – and Kajikhumar Shabdan, an elderly Kazakh poet serving a 15-year sentence for counterrevolution.

On October 25, I called La Yifan, Li Baodong’s deputy. I wanted to know whether Tina would be given a visa. La told me that it had been decided to grant the visa. We discussed possible dates for Tina and my trip to Beijing, and settled on mid-December, subject to confirmation and Tina’s availability.

I flew to Beijing via Narita on December 15, arriving on December 16. The next day I had lunch with Ambassador Randt and his family at the residence. Afterwards I met with Li Baodong at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Two of his colleagues joined the meeting. Tina was soon to land in Beijing. Director General Li commented that the Chinese government did not expect Tina to write an article suitable for publication in the Beijing Review, but it hoped she would be fair and objective. At this meeting I presented a list of Chinese political prisoners eligible for parole.