EVENTS

The Year of the Malevolent Rat: A Post-Mortem

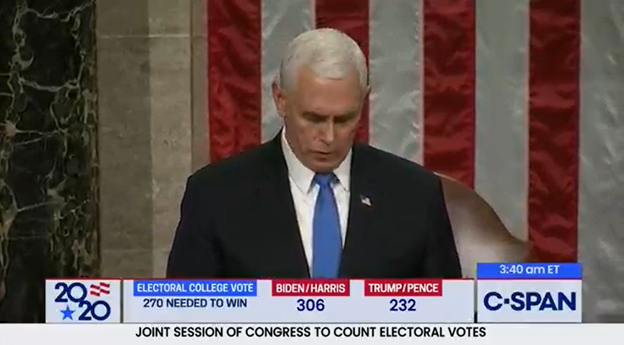

While it would be tempting to throw out all calendars and forget that 2020 ever existed, we will unfortunately be feeling the reverberations of this cataclysmic year for some time to come. Today, President-elect Joe Biden was sworn in, and the Biden team’s approach to China can only be developed with last year’s events in mind. Books will inevitably be written about how 2020 witnessed a sharp, accelerating deterioration of US-China relations. In just about every sphere—trade, technology, national security, human rights—the United States and China clashed. The novel coronavirus, and each country’s approach to the new health threat, proved to be the match that lit the powder keg.

A Moribund Trade Deal

Just a year ago few of us had heard of the coronavirus, and there was even reason to see a small light on the horizon of US-China relations. On January 15, 2020, President Trump’s “Phase One” trade agreement with China was signed, and the hopeful among us wondered if the United States and China would finally reach a detente after nearly two years of trade war. In the agreement, China pledged to purchase over $200 billion in US goods during the 2020-2022 period. “Our relationship with China has now probably never, ever been better,” Trump said in Davos, Switzerland, three days later.

Novel Virus, New Tone

Any hopes of a warming of relations were quickly dashed as news of the spread of Covid-19 threw the world into chaos. By November 2020, China had spent only $82 billion in four key product groups—just 58 percent of its year-end target under the trade agreement. The pandemic slowed the entire world economy, and China recorded two percent GDP growth for the year, well behind its 2019 performance. However, it is obvious that the economy was not the only factor behind the trade deal’s failure.

Just over two weeks after the trade agreement was signed, on January 31, Trump imposed restrictions on non-US citizens who had travelled to China in the previous two weeks, preventing them from entering the United States. This move, made in response to the spread of the coronavirus, didn’t ease the strain between the two nations. By May, President Trump’s tone towards China had become outright hostile: “China’s cover-up of the ‘Wuhan virus’ allowed the disease to spread all over the world,” he said in a Rose Garden speech, in which he also spoke negatively about China on trade, Hong Kong, espionage, and its activity in the Pacific Ocean.

China-focused Legislation & International Policy

Technology has been a particular bugbear for Trump, who wielded trade rules to target China in this key industry. In May, new rules specifically called out Huawei, preventing companies that use US-made semiconductor technology from shipping it to the Chinese company without special permission. Trump cited national security as the impetus for the rule, remarking that Huawei could use the technology for espionage. Towards the end of the year, the United States slapped another harsh restriction on SMIC, China’s chip giant, citing military ties as a concern.

Perhaps the single most incendiary move on the part of the Trump administration towards China came in October, with a nearly $2 billion arms sale deal to Taiwan—a change from the previous US strategy of using a more nuanced touch with respect to the island’s place in the international order. Visits by high-level officials in the American administration were met with howls of outrage in Beijing.

Sanctions & Human Rights

During 2020, dozens of individuals and companies were sanctioned by the United States over a wide range of abuses. Much of the China-focused legislation responded to human rights abuses, with special attention on the situation in Xinjiang, where Uyghurs and other minority groups have been placed in so-called “vocational training centers” since at least 2017. Chen Quanguo, a member of the Politburo Central Committee, was among those sanctioned for policies in Xinjiang. In September, legislation passed the House that would ban imports from companies that use Uyghur forced labor. It ended the year stalled in the Senate. On January 13, 2021, the Trump administration announced a ban on all cotton and tomato products coming from Xinjiang.

On January 19, the last full day of the Trump administration, the US Department of State officially determined that, at least since March 2017, China has committed genocide and crimes against humanity against the Uyghurs and other ethnic and religious minority groups in Xinjiang. This determination specifically referred to the mass internment, forced labor, and forced sterilization of the Uyghurs and other minority groups in Xinjiang.

By year’s end, a slew of US legislation had targeted China; in all, Dui Hua counted more than 300 bills and resolutions passed during 2020. Hong Kong drew special legislative attention from the United States, including sanctions on the top leadership of the National People’s Congress in August for imposing a national security law on Hong Kong the month before. A bill passed by the House in December granting special refugee status to Hong Kongers. International focus has also been on Tibet, and the December 27 pandemic relief bill included the Tibet Policy and Support Act, which threatens sanctions against CCP members involved in human rights abuses of Tibetans.

Dui Hua’s Approach in 2020

Since Dui Hua is able to approach human rights dialogue with China laterally as a non-government entity, the foundation has managed to stay above the fray when it comes to the harsh rhetoric and deteriorating relations between the two countries. 2020 highlighted the limitations of advocating for global human rights within the confines of the nation-state system: discord between nations in any sphere can bring human rights dialogue to a standstill. Throughout the year Dui Hua continued to cultivate all of its channels of communication with the Chinese government. By the end of 2020, Dui Hua had raised the names of over a hundred prisoners and received responses on nearly 40 individuals.

Looking Ahead

Just before the new year, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi offered a more hopeful tone: “China-US relations have come to a new crossroads, and a new window of hope is opening. We hope that the next US administration will return to a sensible approach, resume dialogue with China, restore normalcy to the bilateral relations and restart cooperation.”

Only time will tell how much President-elect Biden’s policies will differ from Trump’s in key areas. Biden’s administrative picks, such as China-critic Katherine Tai for trade representative, signal that he is unlikely to immediately move away from some of Trump’s stances. However, the Biden administration’s rhetoric towards China will likely resume a more diplomatic tone and could well mark an easing in tensions between the two countries, creating an atmosphere in which more fruitful human rights dialogue can take place.

EXCHANGES

Exchanges is a feature that explores Dui Hua’s International Symposium on Girls in Conflict with the Law as well as other expert exchanges and dialogues.

“Leave No Child Behind Bars”

The International Symposium on Girls in Conflict with the Law began 2021 with two complementary webinars: “International Perspectives on Girls in Conflict with the Law” on January 14 and “Juvenile Incarceration: Alternatives” on January 15.

During “International Perspectives,” Meda Chesney-Lind of the University of Hawaii explored the trends that have defined girls’ delinquency and the problems within the justice system that lead to further exploitation. Manfred Nowak, Independent Expert on the UN Global Study on Children Deprived of Liberty, explained the key findings of his study, noting that even as research lacks key data, it is clear most nations are not doing enough to meet their obligations concerning the rights of the child. Nafula Wafula of the Commonwealth Youth Council took the audience through the experience of a girl caught stealing in Kenya, revealing how an under-resourced system shaped by the remnants of colonialism continues to isolate and stigmatize girl offenders.

While the three presenters differed in focus—Chesney-Lind’s research was on the United States, Nowak’s study was based on 118 questionnaire replies from 92 countries, and Wafula’s presentation related to Kenya and neighboring Uganda and Tanzania—common cycles emerged across all three presentations. Perhaps most urgent is the lack of dedicated space for girl offenders throughout the world, mixing them with adult offenders, including men, in settings that make them more vulnerable.

“Juvenile Incarceration: Alternatives” took an in-depth look at what rehabilitation actually requires. Superior Court judges Susan Breall and Roger Chan gave a joint presentation discussing the needs of girl offenders and new approaches to effect meaningful change. Dr. Zhang Hongwei of the Juvenile & Family Law Research Center at Jinan University, China, spoke on the issues facing girls in China as well as recent relevant reforms to China’s civil code. The panel was moderated by Judge Leonard Edwards.

Judges Breall and Chan drew on the fact that most girl detainees are dealing with varying levels of trauma, emphasizing the need to treat them as survivors rather than offenders. They argued for a survivor-centered approach rather than a trauma-based approach, calling for community-based solutions that focus on facilitating agency, honesty, and open communication. Dr. Zhang’s presentation detailed rates of juvenile crime in China and recent reforms to the civil code to improve family law. While noting the progress made, such as gender-sensitive approaches in law enforcement, he also identified areas where improvement is still needed.

The International Symposium on Girls in Conflict with the Law is yielding valuable insights to improve juvenile justice systems throughout the world, and Dui Hua will be analyzing and sharing these throughout 2021. As Independent Expert Nowak offered, “Our main recommendation is: leave no child behind bars. There are always non‑custodial alternatives. And by that, give them back their childhood.”

The next webinar, “Girls in Conflict with the Law in Hong Kong and Guangzhou,” is on Thursday, January 28 at 5 pm PST. Presenters include Eric Chui, professor in the Department of Social and Behavioural Sciences; Karen Joe Laidler, Director of the Centre for Criminology at the University of Hong; and Dr. Zhang Hongwei, professor at the Juvenile and Family Law Research Center at Jinan University, China. The panel is moderated by the University of Hong Kong’s Lindsay Ernst.

Go here to learn more about these webinars, the panelists, and the Symposium.

PUBLICATIONS ROUND UP

Featured: Human Rights Journal, January 12, 2021: Tablighi Jamaat and Hui Muslims

Literally translated as “society for spreading faith,” Tablighi Jamaat (TJ) is a transnational movement closely tied to the Deobandi interpretation of the Sunni Islamic teachings. It is often seen as an ultraorthodox sect, and some media outlets have erroneously reported that TJ calls on Muslims to travel the world to convert non-believers. Founded in India in 1926, TJ encourages all members to form small groups to proselytize both in- and outside of mosques.

Read more here.

JOHN KAMM REMEMBERS

John Kamm Remembers is a feature that explores Kamm’s human rights advocacy prior to and since Dui Hua’s establishment in 1999.

Guangzhou Days: Remembering Ezra Vogel

Harvard Professor Ezra Vogel, a widely acknowledged expert and prolific writer on Japan and China, passed away in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on December 20, 2020. He was 90 years old.

I got to know Professor Vogel in the 1980s when, on several extended visits, he resided in Guangzhou conducting research for what was to become One Step Ahead in China: Guangdong Under Reform (Harvard University Press, 1989). He was joined by his wife Charlotte Ikels, an accomplished anthropologist studying Chinese society.

After attending the trade fairs in 1976-1979, I opened the first foreign office in Guangzhou in 1979 and worked out of a suite of rooms in the Dongfang Hotel. I later moved the office to the Garden Hotel. By 1988 I had visited nearly every prefecture in the province, meeting with factories and running agricultural chemical field trials. In this I was aided by my knowledge of Cantonese.

As a long-time resident of the Dongfang, I managed to get my hands on a Hitachi air conditioner. China had purchased several hundred of these machines after the Tangshan earthquake in which a number of Hitachi engineers had perished. The air conditioners spent several months stacked in the heat and humidity of the Dongfang’s courtyard.

Unfortunately, the hotel’s power system could not handle the increased load of multiple air conditioners blasting away, so only a few of the Hitachi air conditioners were ever installed.

It didn’t take long for Ezra to hear about my air-conditioned suite, and he became a frequent visitor. He was staying at Zhongshan University south of the river. In the sweltering heat of the summer months, we would drink beer in the office and sometimes go out for walks to local restaurants and parks. We spent many hours in long conversations about how Guangdong had changed since I first visited the city in January 1976, just as the Cultural Revolution was beginning to wind down.

Guangzhou underwent great changes in the aftermath of the reforms initiated in late 1978, changes that Ezra chronicled in One Step Ahead in China. I had been involved in early joint venture discussions and made some of the first sales to county foreign trade organizations. I willingly became a resource for Ezra. Eventually he asked me to write a chapter for the book, which I gladly did.

While Guangdong was undergoing great economic changes, many of which I chronicled in my magazine Canton Companion, that was not the case with political change. Like all other Chinese provinces, Guangdong was under the firm control of the Chinese Communist Party.

A couple of examples serve to illustrate the dichotomy between economic reform and the lack of political reform.

In May 1982, democracy activist Wang Xizhe was sentenced to 14 years in prison for counterrevolutionary activities. Wang was a member of the Li Yizhe group that composed and put up a long essay on democratic and legal reform in 1974. The group was eventually imprisoned, but they were exonerated and released not long after the Gang of Four was overthrown in October 1976. While other members of Li Yizhe adopted relatively low-key lifestyles, Wang remained politically active. (He was released early in 1993 after my spirited intervention with China’s State Council.)

While Wang’s trial was taking place, the China Hotel, China’s first foreign joint venture hotel, was being built adjacent to the Dongfang Hotel. This was the brainchild of Hong Kong businessman Gordon (now Sir Gordon) Wu. He was and remains a firm believer that economic change will eventually lead to political change. In addition to the China Hotel, he built the Shenzhen Guangzhou highway as well as the Shijiao power station in Guangdong. The latter venture significantly increased power supply in the Pearl River Delta.

On our walks around the city, Ezra and I often came across announcements of executions. These announcements were written in black ink on large posters with a distinctive red check – indicating that the execution had taken place – on the bottom of the announcement. I referenced the wave of executions that followed the first Strike Hard Campaign in 1983-84 in my chapter, estimating that Guangdong accounted for 1,000 of the 10,000 executions in China in the autumn of 1983. I also devoted space to chronicling worker unrest in the special economic zones.

By 1988 the manuscript – “With a contribution by John Kamm” – for One Step Ahead was ready for footnoting and editing. Unexpectedly, political unrest broke out in Beijing and other Chinese cities including Guangzhou. Many people were killed or wounded, and thousands were detained. To people like Ezra Vogel and me these events were shocking. My views of China changed, and I began to work on human rights.

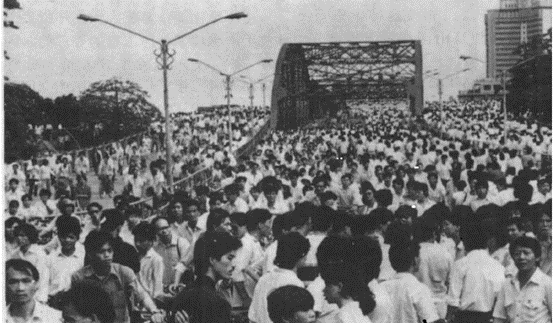

Ezra was especially upset by the arrest of young students and teachers. Chen Pokong was a teacher at Zhongshan University while Ezra was in residence. He was also the honorary president and advisor to the Guangzhou Students Autonomous Federation, a group that distinguished itself by organizing blockades of bridges over the Pearl River during May and June 1989. He founded a political party and issued a manifesto calling for human rights and rule of law. Chen Pokong was sentenced to three years in prison for counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement. Released after serving his full term, Chen returned to activism and was sentenced to a two-year term of re-education through labor in 1993.

I took a special interest in the case of Yi Danxuan, a student leader who, like Chen Pokong, organized the blockade of the Pearl River Bridges, He was sentenced to three years for counterrevolutionary activities. Identified as a businessman, I announced his release one year early on August 13, 1991.

A student activist who received the longest sentence – 10 years – for June 4-related activities was Chen Zhixiang, a teacher detained for writing anti-government slogans throughout the city. He was released four years early in November 1995.

As the publication date of One Step Ahead neared, Ezra wondered whether to address the killings and arrests of the 1989 protest movement. I encouraged him to do so. Finally, he penned a preface to the book that was released in December 1989. The opening sentences reveal the strength of Ezra’s condemnation:

“In June 1989 the massacre of students in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square stunned China and the rest of the world. It was not the first time that China’s rulers had ordered soldiers to slaughter unarmed civilians. . .The 1989 massacre was the first such atrocity played out under the vigilant eye of modern telecommunications, and it was thereby instantly and dramatically accessible to people everywhere. It marked the definitive end to an era in which the Chinese state could monopolize the flow of information in and out of China.”

One Step Ahead was to play a role in another case that brought Ezra and me together. In the summer of 2000, Xu Zerong, a Hong Kong resident and Guangzhou professor, was arrested for trafficking in state secrets. Xu, aka David Tsui, had translated an early draft of One Step Ahead and had stayed in close contact with Professor Vogel. The Harvard professor asked me to intervene on Xu’s behalf and I did so, liberally using Vogel’s name in my pleas to Guangdong officials. Vogel was well-liked and influential in Guangdong Province. His interest in Xu Zerong’s fate played a role in the decision to release him two years early, in June 2011.

In his many years in academia and government service, Ezra Vogel was seen as a mild-mannered, cautious man little interested in the struggles of the Chinese people for human rights and rule of law. That was not the Ezra Vogel I got to know. He worked behind the scenes on important causes like helping scholars disliked by Beijing secure visas. He was a long-time supporter of Dui Hua, and the source of much sage advice. He helped organize some of my speeches at Harvard. Ezra tried to bring the countries together, an increasingly difficult task in recent years. He will be deeply missed.